The Power of Art

A conversation with patron of the art and philanthropist Francesca von Habsburg

Irene Gludowacz*

17/02/2016

Founded by Francesca von Habsburg in 2002, Thyssen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary (TBA21) is a thriving platform for 21st-century art headquartered in Vienna. Apart from supporting and commissioning projects in the international art world, the private foundation reflects Francesca von Habsburg’s unwavering vision and mission to connect the “universal language” of art with science and the environment, as well as to address economic, social, and political issues. Fully committed to her cause, she does not shy away from effort and expense. Drawn to projects that challenge her understanding and provoke her as well as others, she shows courage and gives insights into her many areas of engagement. Francesca von Habsburg is the daughter of magnate collector Baron Hans Heinrich von Thyssen-Bornemisza de Kázon and Fiona Campbell-Walter.

Your father’s family has been collecting art for four generations now. How has your family background influenced you?

I lived at the Villa Favorita in Lugano-Castagnola at a time when it was closed to the public. It began opening its doors slowly in the 1980s, and then upon request on weekends. My father regularly entertained some of the most influential personalities in the art world. The highlight was always a private viewing of the sublime art collection just a stone’s throw from our dining table. I am frequently asked which artworks from my childhood influenced me most, and on reflection, it was not the art but the people I had the privilege of meeting at that time. It was not the great exhibitions that my father took me to see in New York, St. Petersburg, Paris, or Tokyo; it was spending time with intimate art lovers such as J. Carter Brown, Sadruddin Aga Khan, Giovanni Agnelli, Mikhail Piotrovsky, Lord Gowrie, Ursula Dreyfuss, Norman Rosenthal, and Simon de Pury, among many others, and eclectic people from those times. I learned that art is worth so much more when you can understand it through experienced and cultured eyes. Pioneers of their times, they were tremendous innovators and had great, ambitious projects.

In the eighties your father loaned major works from his collection to the Soviet Union. No Western private collector had done this before during the Iron Curtain era. How did this unique project start?

When my father opened up his collection, we received a letter from the director of the Hermitage in St. Petersburg, who wanted to borrow 25 paintings from the collection. Simon de Pury, who was at that time the director of my father’s collection, went with us on the first trip to the Soviet Union. In those days of the Cold War you couldn’t even talk to the Soviet Union; it was a grey area and sort of forbidden. I remember that Sotheby’s was trying to get a foot in there too, and we met with Agnes Husslein, who was at that time with Sotheby’s. We were going around the Hermitage late at night with the old director, Mikhail Piotrovsky’s father, Boris, after a long alcoholic dinner in his chambers, and then with a torch down into the old wine cellars. Most of the modern artworks were not even on view because it was considered “perverted art.” No insurance company wanted to cover the loan of the paintings, which were at that time valued at around US $40 million—top-class old masters and impressionists. My father simply said: “This is the deal: If there is no insurance, there is no guarantee of ever getting them back. If you want to borrow my private paintings for your museum, you have to lend me, at the same time, paintings of the same quality and value from your collection, with trains and trucks going in both directions at the same time. Otherwise you won’t get my paintings!” It was like in a James Bond movie. The Soviets were speechless and asked my father, “Do you mean you want to hang them in your house?” My father responded very provocatively for that time, “Yes, we’ll bring the very famous paintings that are now in your collection into a private house, one that you took them from a long time ago.” Most astonishingly, they agreed! We then had queues of thousands of visitors at the Villa Favorita who wanted to see these works, which had never before been shown outside of Russia. This was around 1982. My father’s collection was also shown in Moscow, and finally they gave him a live TV broadcast—just a few days after the Korean airliner was shot down in 1983. He said live: “We made so much incredible progress in the past, but if you shoot down civilian aircraft, in the future nobody will talk to you again if you want to move forward.” The director of the TV broadcast was taken away, and we don’t know what happened to him.

My father was using art as a political weapon—and the moment you realize that you can effectively change the world with art, it becomes an immensely powerful tool. It is not just a decoration, as we all know, and it is not only a reflection of our social values. It is something that you can use because it attracts power—people of wealth, power, and influence feel very motivated by it. Art is an instrument, and in this day and age it is a vehicle for a lot of egos and a power thing, in terms of who has what work of art.

Ragnar Kjartansson. The Palace of the Summerland. Team of The Palace of the Summerland. Photo: Lilja Birgisdóttir, 2014

Looking at the spirit of your father, whose collection is known for its chronological approach to the history of art from medieval religious art right up to American art from the seventies and eighties - how did you come to focus on contemporary art?

When I was in New York at a young age with my father, we met with Lichtenstein and Warhol—my father was somehow connected there, too, but more tentatively. Contemporary art was not his thing at all. His collection really stopped with the impressionists, expressionists, the Russian avant-garde and some American abstract expressionists and other abstract works, but only a few. Actually, it was my mother who was much more interested in contemporary art from that time. She really loved works by Cy Twombly when they were priced at 10,000 DM! But she still could not convince my father—instead she convinced him to acquire the first Emil Nolde for his collection. She did most of the buying of the German expressionists that covered the walls of their private apartment in the Villa Favorita at that time.

I remember it was in the seventies, when I was visiting New York together with my father, and quite by accident, I stumbled into a very comprehensive exhibition of minimalism at the Whitney Museum—this drastically changed my life. I found myself immersed in a completely new aesthetic, and I completely identified with it. I can see now, forty years later, how much it influenced me. Some of the earliest works I bought for TBA21 were from Cerith Wyn Evans, Carsten Höller, Janet Cardiff, Olafur Eliasson, and Angela Bulloch, all of which had a fragrance of minimalism for me, which was a reflection of my memory of that show. Such extraordinary power in such simple artworks. It was not academic for me; it was the beginning of a love story.

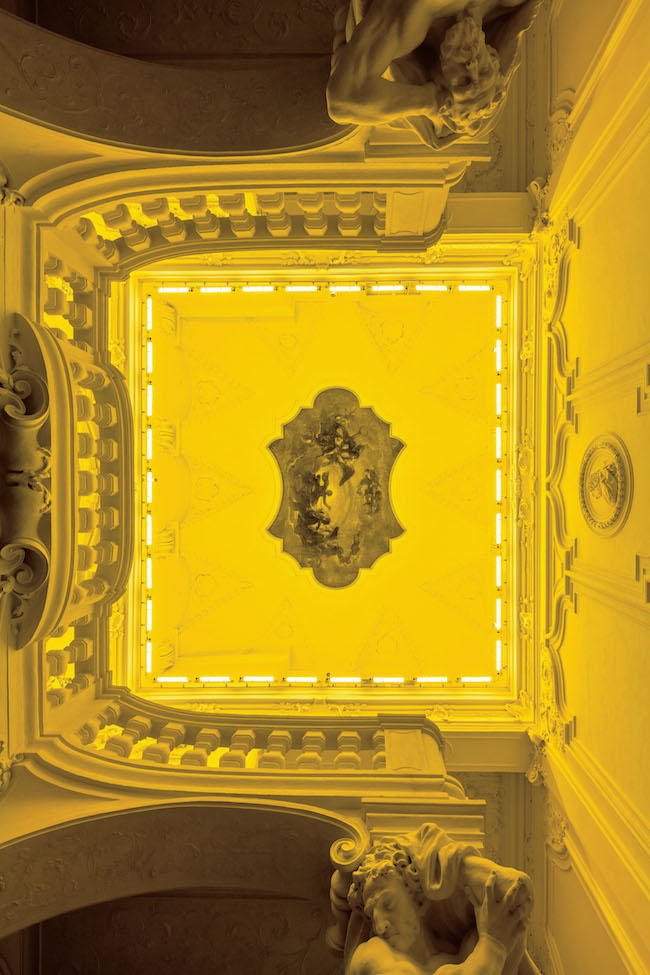

Olafur Eliasson. Yellow corridor, 1997. The Juan & Patricia Vergez Collection, Buenos Aires. Installation view: OLAFUR ELIASSON: BAROQUE BAROQUE, The Winter Palace, Vienna 2015, Photo: Anders Sune Berg, © 1997 Olafur Eliasson

What brought you and the team of TBA21 to commission and support contemporary art projects internationally?

Commissioning works of art is not an easy exercise; it takes skill, sensitivity, and a great deal of courage as well as faith in the process. Otherwise you will not give it enough space and fermentation to develop fully. Artists are extremely open to collaboration, as they need to explore their own limits as part of their practice. It is indeed a process that TBA21 has pioneered as the means of establishing a unique collection that defies traditional categorization. In this space, I am also a creative protagonist of a collaborative project that requires more than just getting two parties together. With the support of a highly qualified team, we establish the process through which the artists, architects, composers, scientists, programmers, and environmentalist can all explore their extreme positions. It is an immensely rewarding experience. I am looking for synergies among our different approaches, and the most prominent common denominator is our philanthropic spirit.

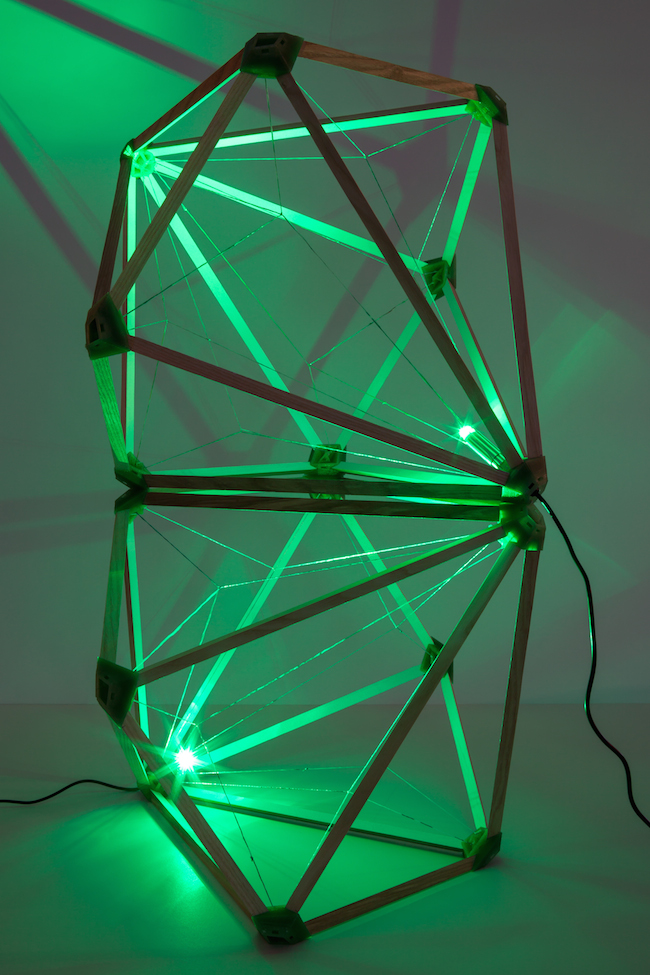

Olafur Eliasson. The organic and crystalline description, 1996. Thyssen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary Collection, Vienna. Installation view: OLAFUR ELIASSON: BAROQUE BAROQUE, The Winter Palace, Vienna 2015, Photo: Anders Sune Berg, © 1996 Olafur Eliasson

In 2014 TBA21 launched an exhibition project with Ragnar Kjartansson, “Palace of the Summerland,” which took on dimensions that we had not previously explored! It was epic! At the moment there is an extensive solo exhibition by Olafur Eliasson, “Baroque Baroque,” featuring new works by the artist and presented at the Winter Palace in Vienna, which inspired Versailles to invite him to create an exhibition there. I love the fact that we could pioneer a new type of exhibition concept for Olafur. Otherwise he would have been trapped in white cubes all his life, at least when he is not creating interventions in nature, which to my mind are his strongest works. This exhibition was a collaboration with TBA21, the Belvedere Museum, and the Juan and Patrizia Vergez Collection. I enjoy working with visionary collectors whose hearts are in the same place as mine.

TBA21 has a “department” called the TBA21 Academy, which is linked with science and nature. What type of projects is the Academy involved in?

I established TBA21 Academy as a platform from which I can take this interdisciplinary work to another level, not only engaging artists but also taking science and conservation as our point of departure. We are taking artists out of their studios, scientists out of their labs, and bringing them together, along with other cultural producers, and inviting them to the most remote places. With the Academy’s director, Markus Reymann, we created TBA21 The Current, which is a three-year exploratory fellowship program in the Pacific that aims to support new processes of knowledge production, as opposed to art production, and encourages and inspires new solutions for the environment. A tailor-made tool for commissioning and disseminating ambitious and unconventional projects beyond traditional art categories, The Current embraces the notion of the journey as a goal in itself.

TBA21 Founder and Chairwoman Francesca Habsburg diving a B-17 World War II bomber called Black Jack in 47 meters of depth at Boga Boga Milne Bay, Papua New Guinea, October 2015. Photo: Craig de Wit. Copyright TBA21

How is the The Current structured, how does it work, and what are its future plans and missions?

Participants in The Current are joining an expedition on the research vessel Dardanella, led by three curators whom we refer to as expedition leaders! The Current’s first two expeditions, guided by Ute Meta Bauer (founding director of the NTU Centre for Contemporary Art Singapore) and Cesar Garcia (founding director and chief curator of the Mistake Room, Los Angeles), both took teams of artists and researchers to Papua New Guinea in autumn 2015. Swiss curator Damian Christinger will embark on a voyage to French Polynesia in June of this year. Each expedition results in a convening that takes place a few months later: a public presentation that is informed by the participants’ experiences at sea and the joint fieldwork; at the same time, it is a gathering of artists, scientists, and local stakeholders who have emerged as committed agents and voices of change. The first one will take place in Kingston, Jamaica, on the 15th to the 20th of March this year. We are combining it with the recent creation of the Fish Sanctuary in Portland, and the establishment of the Alligator Head Foundation dedicated to supporting the local fishermen most affected by the sanctuary. It’s a holistic program incorporating theory and practice, experimentation and entertainment. And Jamaica is so vibrant at the moment with its burgeoning art scene; we are supporting the establishment of its first independent art institution space in Kingston.

Sunset with the Dardanella and dugouts, Papua New Guinea, October 2015. Photo: Francesca Habsburg. Copyright TBA21

The first thing we realized while on location in the remote islands in the Pacific is the huge impact that climate change is having on the communities struggling to survive in the Pacific. If there is no rain for extended periods, this causes massive droughts, and seasonal changes prevent the normal cycle of plantations; with extreme weather conditions and rising sea levels, people are literally having to leave their remote communities, and there are increasing numbers of climate refugees. We brought gifts such as toys, books, medicine, clothes, food, and water to the people of Vanuatu, which had recently been devastated by the cyclone Pam. Throughout the pacific we distributed about 300 solar lights by Olafur Eliasson, which we gave to the indigenous people who have no light at all. All these villages rely on their oral traditions that will be lost if they have to relocate. By understanding their traditions, and by listening to their issues and fears, you begin to see a pattern which translates into a better understanding of the complexity of the Anthropocene and how it affects these parts of the world. Whilst they are responsible for about one to two percent of global emissions, their communities certainly suffer 99% of these emissions' effects. It is then that you have to ask yourself, how can we become an agent of change to redress this balance if carbon trading is not the answer? Artists have been historically the voice of reason, and today they are the ones who defy traditional market-driven ambitions to instead focus on the urgent issues of our time in a way that empowers people, and inspires them to join the movement.

Tomás Saraceno. Aerocene - Cloud Cities, 2015

What are your ideas? How will you combine these major issues, which are extremely relevant today, with art and artists?

We need to provide the resources required to rapidly move away from fossil fuels and prepare for the coming heavy weather; this would also pull huge swaths of humanity out of poverty, and provide many services now lacking – from fresh water to electricity. We cannot continue mitigating and adapting to climate change; in the grim language of the United Nations, we need to collectively use the crisis to leap somewhere that is, frankly, a better place than we are in now. This is why I have dedicated the work of my contemporary art Foundation TBA21 to working with artists who can inspire and explore new solutions that we all can focus on, solutions that will move us towards a collective achievement of a better and cleaner future. I am convinced that the artists that I am working with have ideas worth exploring, supporting and investing in – visionary projects like AREOSCENE by Tomas Saraceno. Because he helps us dream of solutions and gets us out of this mindset that we are locked into and paralyzed by. The future is a huge wake-up call, telling us that we need to evolve!

Green light. Prototype by Studio Olafur Eliasson © Studio Olafur Eliasson 2016

We also have an exhibition with workshops this April, with Olafur Eliasson, called “Green Light”. It is a response to the terrible situation that the climate- and political refugees find themselves in today in Europe. The Green Light project responds to a situation of great uncertainty, both for refugees, who are often caught up in a legal and political limbo, and for the European societies that welcome them. Olafur Eliasson says: “It is my hope that Green Light will shine light on some of the challenges and responsibilities arising from the current refugee crisis in Europe and throughout the world. Green Light is an act of welcoming, addressed both to those who have fled hardship and instability in their home countries and to the residents of Vienna. It invites them to take part in the construction of something of value through a playful, creative process. Green Light attempts to question the values of similarity and otherness in our society and to help shape our feelings of identity and togetherness.”

March for climate change, Vienna, 2015, Photo © Sandro Zanzinger/TBA21

Last year, as I saw things around me spiraling out of control around us – everything from politics and religion to the health of our planet – I decided to align my personal convictions about creating a healthier and safer planet together with the work of the Foundation – so that I could breathe again. I realized that my world had split into two, and to bring back some sanity, I needed to bring these two worlds together; I quickly realized that this was absolutely the right thing to do. And since I took that decision, I have been overwhelmed by the most amazing projects that defy traditional categorization, that want to articulate a shared passion for the world we live in. And at the same time, I am at peace with myself. The Foundation is doing better work than ever, and I feel that there is now hope, and that we can extract ourselves from a decomposing world, one that is stuck in repetition and ignorance and an insane addiction to fossil fuels. We can get ourselves out of this mess, and we must; and for this, we do need to prepare ourselves for massive changes – on a seismic scale. Art is a true voice that can help us better embrace that change and change with it, not against it.

Francesca von Habsburg. Photo: Irina Gavrich, © TBA21, Vienna, 2015

* Based in Vienna, Irene M.Gludowacz M.A is an author, curator and communication expert for foundations, museums and corporations in the international art world. She is also the co-author of the books “A Passion for Art: Art Collectors and Their Houses” (2005) and “Global Art” (2009)