Restoring names

Sergei Timofeev

28/12/2011

I haven’t met so many people in my life who would match exactly to what they are doing. Say, absolute physician, absolute politician or absolute collector, especially collector of art. Usually the latter makes elderly, set people with the capital made. For them, paintings and sculptures in their house are the proof of the status they have achieved, and, in some sense, investment in their future. It’s a different story with Anatol Pedan. He has been fascinated by collecting since his early youth, and this occupation in fact has affected him as a personality, shaped his life journey. Besides, he is not a mere collector, but an explorer, who lifts the veil of the oblivion on works, whose byline got lost in the turmoil of the 20th Century experience. And it was exactly the name of his collection exhibited at the Latvian National Museum of Arts in this year’s August and September: Restored Names. Along with the exhibition, large and tastefully designed catalogue was released, many articles of which were written by Anatol Pedan himself.

“Both exhibition and this entire project in fact reflected the multicultural environment of our city. And although there is the evident multiculturalism crisis in Europe, I’d like to show that Riga has always been a melting pot of cultures. Also, the catalogue itself has been released in three languages. There are not only Russian works of art on show, but also Latvian, Baltic German, Jewish, Polish and Ukrainian artists who lived and worked in Riga, were connected to this city, but at the same time were affected by Russian school or did their studies in Russia,” tells Anatol Pedan.

has decided to present to its audience one of the most dedicated art collectors from Latvia, so we have arranged the meeting at his small gallery filled with paintings, named Haberland, in the Old Town, near Riga Castle. The name of the gallery is yet another restored name. Christoph Haberland was the chief architect of Riga in the end of 18th Century. History and contemporaneity seem to form the unbreakable union in this collector’s life. But what is his own personal story?

- It began quite a long time ago, when I have only graduated from school. In fact, from the early childhood I was surrounded by people whose houses were filled with paintings. My mother was the engineer of the utility lines in many buildings in Riga. We were visited by lots of her friends and colleagues: architects, engineers. The house we lived in was named “house of engineers”, inhabited by many people of art. All of this created a special environment, so my interest towards art has risen already at the age of 17. The first thing I started with was collecting my library. After graduating from school I entered Riga Technical University (former Polytechnic Institute of Riga) and, while studying, I was soaking like a sponge all kinds of information on artists, art unions and art movements. I have purchased many encyclopaedic editions, such as Brockhaus and Efron dictionary, and I am still using them almost every day. I am often asked, why do not use the electronic version of this dictionary. But am I a book-man, I was brought up in the traditional, old-style manner, thus gained piety towards the book. To take a volume from a shelf, to hold it in my arms – it is a pleasure to me.

At first I took an interest mostly in applied historic disciplines, such as heraldry, faleristics and numismatics. I received my first painting in oil technique when I was about 18, it came from a very good collection. It was a work of an unknown 18thcentury West-European artist: such a cheerful genre piece named “Revellers”. It stayed with me for 30 years. Recently I have parted from it because I have made a decision to concentrate on Russian school and realized that one can’t have it all.

Sergei Vinogradov. At samovar. 1920s-1930s. Oil on canvas. Collection of Anatol Pedan

I already perceived painting rather emotionally back then, but pieces of art were mostly part of the interior, decoration of the inner space to me. Also my interest in heraldry pushed me in certain direction: I had collected many rare prerevolutionary editions on the subject. In these books I often saw engravings painted with water colour, and I took an interest in engravings and lithography. Nowadays, most collectors do not pay attention to this genre, everyone wants to collect painting, especially oil painting, because it is something fundamental, something worthy. They pay little attention to the drawing, engraving, posters, art postcards in lithograph. But for me all these genres are masterpieces with their own attraction. I began with them. Later, though, I realized that I am still mostly attracted by painting. >>

I feel some sort of vibe, some sort of radiance coming from the picture. When a work comes to me, I put it in front of me to a special place to figure out whether it’s going to be on the wall or going to the storage. And I watch it for days, some even for months. It’s not like I’m studying it with a magnifier... No, I am just watching it, trying to understand what kind of emotion it is arousing. It happens that I am waking up in the middle of the night, because the vibe coming from the painting is so powerful I can’t even sleep. And this vibe can be either positive or negative.

A friend of mine, a dowser, says that it is very important not to store oil paintings horizontally, because not everyone is able to stand energy coming from paintings.

Aleksei Bogoliubov. View of Palermo. 1855. Oil on canvas. Collection of Anatol Pedan

Why not horizontally?

Presumably, in this case, the radiation emanates the wrong way. This effect mostly refers to the works in oil technique. Graphic art, pastel works and aquarelles can be stored in maps, yet all the paintings in my collection right now are kept vertically.

Well, sometimes I wake up somehow anxious from this vibe – it is not necessarily negative, but very strong. A Latvian collector Janis Zuzans, our Latvian Tretyakov, a man of taste and generous spirit, is someone I discuss such things with, and he once told me that works can be covered by a cloth for the night, the same way you cover a parakeet cage. And I swear, this is true – a true masterpiece in some delicate way directly interacts with a human.

Once I purchased the work of Konstantin Visotsky named “Bisons”, which was restored for me, same as many other works, by Natalia Kurganova, Highest category restorer from the Museum of Foreign Art. So, I have put it on the wall, planning to keep it there for few days and then to replace it with something else. I tried to change it, I have put different other works there, but brought it back in few days. Sometimes a strong interaction with the paintings happens to be. Other works, again, keep changing.

Has your professional life always been tied to collecting?

In Soviet times any kind of collecting was not welcome at all. I was a member of Riga City Collectors’ Society, the official organisation, and still collecting could only be viewed as a leisure activity, outside of working hours. I received a technical degree and spent many years in the energy engineering industry: I have worked for quite a while in Latvenergo. Already when Latvia had regained its independence I have made a decision to fully commit to art. At first, I did the expert evaluation of art pieces until mid 1990-ties, then I realized that it is the best for me to work alone and not being distracted by anyone else. At that time the vector of my collecting began to set.

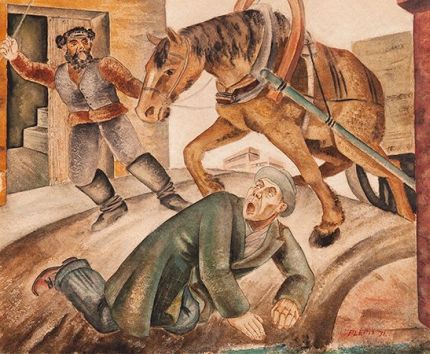

Janis Plepis. The Event. 1931. Watercolour on paper. Collection of Anatol Pedan

I have to say that already before that, in Soviet times, fate brought me into contact with large scale collectors – not middlemen, not art dealers, but true collectors. One of them was, for example, Alexander Perelman from Leningrad, the collector of playing cards and card games attributes: we all have been keen of playing card battles. He had rather many paintings on that subject. A. Perelman was working as the chief of the technical division of “Aurora” publishing house which released classy art catalogues, I usually received those from him. Later his collection was donated by his spouse to the Benois Family Museum in Petergoph. This museum doesn’t even have to be sponsored by state since there is persistent interest towards this collection.

Aleksandr Kramarev. Poster for Maikapar Tobacco Factory (2nd version). 1923. Tempera on cardboard. Collection of Anatol Pedan

During one of the meetings I got acquainted with Ilya Silberstein, whose motto “True collecting is creating” has also become a core motif of the book dedicated to my collection. I. Silberstein is the venerable collector, doctor of arts, he established the Museum of Private Collections in Moscow, next door to the Pushkin Fine Arts Museum. He told me back then: “Young man, you should collect only the pieces you like.” This resonated with what I thought myself.

Does anyone collect something strange to oneself?

You know, yes. And there are many such people. It’s not like it is something strange to themselves, but something that is not close. Although, it might be rare, prestigious, and status-enhancing. These are probably not the best works of a certain author and not even the subject the person would like to see hanging on one’s wall. You know, such as “Beheading of St. John the Baptist”. But even at the Christie’s Russian Art Sale one can hear people saying: “That one tycoon does have it, but I don’t...”

This is not my kind of approach. All the works in my collection were chosen by a single principles: do I like it or not. But, of course, there are works which I want to see daily, the other ones I only take out once per 5 or 10 years, put them on the wall for a while, get some emotional boost and then put them back in the storage.

I do not collect art by periods either. Well, how was my collection shaped to the look it shows in the exhibition at the Latvian National Museum of Art? Just like many other important decisions in my life, this understanding came to me in the morning. Usually, right when I wake up, I already have certain thought in my head: ‘I have to do this and that”. And one fine day I suddenly realized that my collection turns into a single chain stretching from 1830s to 1980s, how I call it – 150 years of Russian art.

Aleksei Yupatov. Duke Aleksander Nevsky. 1944. Coloured ink on paper, author’s technique. Collection of Anatol Pedan

I can’t explain why it happened this way. I have only collected what I liked. I probably could have purchased something from earlier period, from 18th or early 19th century. I even had the works like this, but I let them slip out of my hands because I didn’t feel the same right vibe which I get from later period works.

Why have you decided to exhibit your collection at the Latvian National Museum of Art, not at a gallery?

In fact, everything comes from deep inside, from some sort of root impression. I remember my mom taking me to the Museum of Art for the first time when I was 6. So, I climbed up the steps, entered inside, and there was my first impression: pillars, golden stucco works, and this special scent, scent of Hermitage, scent of the museum. I am quite a sensitive person, and probably this affected my consciousness a lot. Even my parents probably didn’t realize what sort of shock to me it was. Since then the Museum for me is the Temple of art from the capital ‘T’, something incredible. To have my collection exhibited at the Latvian National Museum of Art is the great honour to me, and I am very grateful to the Museum for its confidence in my collection. I will never forget it.

Vase Jurmala. 1930s. Porcelain, overglaze painting after S. Vidberg’s sketch, gold. Workshop Burtnieks, Riga. Collection of Anatol Pedan

I also entrust the restoration of my paintings to the museum professionals only, because my single experience with so called ‘private restorer’ was very unsuccessful and I have never repeated it. I am also glad to have met restorers of paper, engravings and aquarelles. It’s an incredibly difficult task, even more difficult than restoring oil paintings. On my side, I always try to share, and I do share the information from my archives with museum staff, and I also provide works from my collection for thematic exhibitions at the museum.

Let’s go back to your collector’s career. So, mid 90-ties...

In the mid 90-ties we can call it already quite a professional life: collaboration with art galleries and antiquarian salons, every day trips around the city and not only in search of new works. There were cases when I went out for 5-6 times a day to take a look at something, to exchange or to purchase. I had made a good exchange fund already in Soviet times, when it cost less. Back then, it became clear to me that the works I have make an entire picture. There is amount of works of certain periods and groups that can make collection.

Boris Bilinsky. Easter. 1920s. Oil on canvas. Collection of Anatol Pedan.

At the same time I was doing the research all the time. For example, there is the story of how I have got the work of Boris Bilinsky “Easter”. I purchased it in an art salon in Riga. Its owners had found it in an apartment, where it was hanging at the wall, all covered in dust. In the early 1990ties, I was examining the catalogue of Nikita Lobanov-Rostovsky and saw the black and white self-portrait of Boris Bilinsky. It just stayed in my memory. And, after so many years, it evoked such an association in me: “I have seen this face somewhere.” I came home and struggled to remember... and – yes! I opened the catalogue and there it was! Same signature: Б.Б. (Boris Bilinsky). Same face. He portrayed himself grotesquely in Russian traditional manner among merry Easter crowd.

Another of my discoveries, “Fight for Europe”, also came to me as an unknown artist’s work. It also stood on the floor of a gallery among other pictures for two years. The gallery owner told me: “Well, if it was signed by Zardins...” But I saw completely different manner in it, completely different energy. And the signature said A. Ventuel. The gallery owner couldn’t find any traces of this artist anywhere. As for me, I studied German in school, so I realized that “eventuell” means “eventual”, and it must be a pseudonym, not a name. So, I looked at it and thought: “I have seen these long hands somewhere before”. I realized that I know the manner of this artist very well. I purchased the work, brought it home, thought a lot about it, and then woke up in the middle of the night... I usually am a calm, contemplative person, and here I wake up at 3AM with my head humming. My first thought is to go to the bookcase, to open the album “Russian Graphic Art” and to find Masiutin’s work from the cycle “Seven Deadly Sins”. I open it, compare to this recently purchased work and – yes! – it’s the same manner, same composition, same stretched hands.

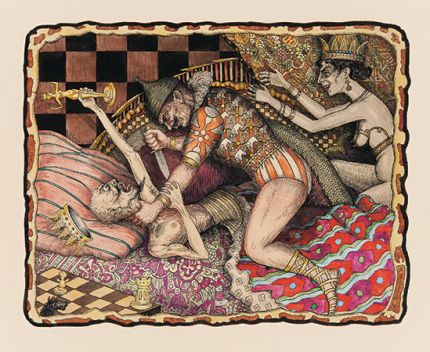

Vasilii Masiutin. Fight for Europe. 1940. Ink, watercolour, silver on paper. Collection of Anatol Pedan

Sometimes I see the work and I know it’s something extraordinary, I definitely have to have them. There are works that open up slowly, and some will probably open up in quite long time.

So, I needed a place to practise all my collector’s activities. I had to sell several works, for example, one of Bogdanov-Belsky, and I regret a lot that it is not in my collection anymore. In 2002 I managed to purchase this place in Pils Street, it is a bit aside from usual tourist paths, but I don’t need them either. My gallery has never worked as a public sales gallery; it is rather a research centre, where I sometimes organize demonstrations, but only after a special invitation.

I am not an entrepreneur by nature. My friends say that it’s too bad. I have many works that formerly had interest in me, but now the whole groups are put away. Probably, I will eventually come to this and put them to sale after we finish the reconstruction of the gallery.

How did you come up with the name of your gallery?

The name “Galerija Haberland” is a tribute to my mother, who took part in many building projects in post-war Riga. Also, name of Christoph Haberland is not so renowned in Riga, even though in the end of 18th century he has built more than 20 urban Classicism style buildings in the Old Town.

At the ‘Restored Names’ exhibition. In the centre Ludmila Neimisheva, Chief art collection supervisor of the Latvian National Museum of Art and exhibition curator, holds discourse with Alexis de Tiesenhausen, International Head of the Russian Department at Christie's.

So, it is possible to say that now you are working on your collection, on your gallery. You are selling something, purchasing something...

Yes, like all the collectors do. And my collection has grown quite large. Mostly, in such cases, collectors hire a professional art expert to classify it. But I like to do it myself, I like to work with archives, to gather factual material. At the end of the day there even was the exhibition and the catalogue released. But its content is only a part of the entire collection: it is much larger. There are lots of graphic art and the entire series of theatrical works – it is rather a separate layer – and many other things.

I have just returned from London where I attended traditional events of “Russian Week”, have had meetings with staff from Russian Department at Christie’s, where the presentation of my book “Restored Names” took place. I have also met Alexis de Tiesenhausen, International Head of the Russian Department at Christie's, a professional, and a tireless researcher, who wrote the introduction to my book and visited the opening of my exhibition in Riga. In London I have personally met many collectors of Russian art and researchers. Nikita Lobanov-Rostovsky, Ivan Samarin, Valery Dudakov – these names need no comments. Probably, these meetings also could help to lift the veil of the oblivion on the entire series of other works from my collection, authors of which are remaining unknown by now.

“Restored Names” exhibition catalogue

+++pagesplit+++