“Collectors are born, not made”

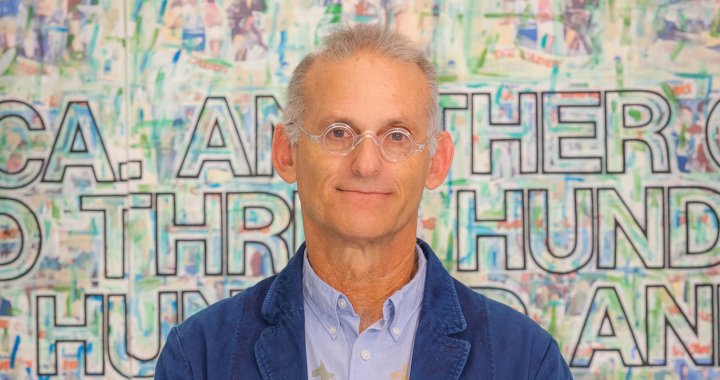

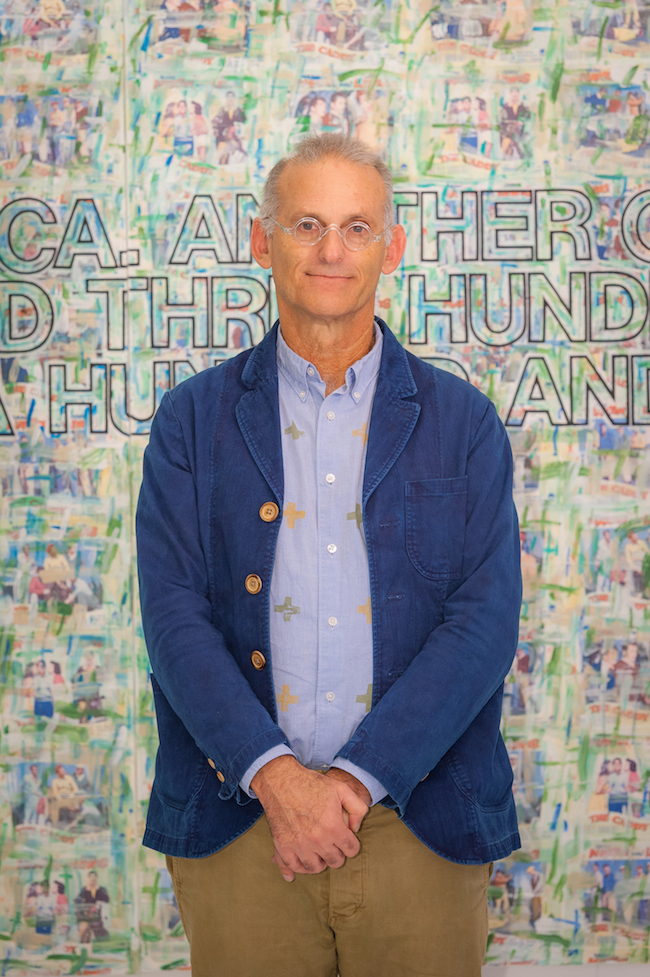

An interview with American art collector and curator Robert M. Rubin

05/03/2017

I was introduced to the American art collector and curator Robert M. Rubin by the art collector and dealer Daniel Wolf, and I met Wolf through the art collector and photographer Jean Pigozzi. I must say, I am deeply thankful to all of them for these wonderful, inestimable experiences.

Even though the term “a Renaissance man” has become somewhat clichéd, it seems the most precise description in the case of Rubin. A former Wall Street commodities and currency trader (over the course of his 25-year-long career on Wall Street he served on the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Foreign Exchange Committee and President Clinton’s Commission on Capital Budgeting), Rubin has advanced degrees in European history and theory and history of architecture from Columbia University. He is a passionate collector with encyclopaedic knowledge in many different areas: as a youth he collected postage stamps, coins and comic books; as an adult he turned to automobiles; and now, later in life, his interests include Hollywood screenplays, contemporary art, design and architecture.

Pierre Chareau. Maison de Verre (1932). Paris, 2016. Photo: Mark Lyon

Rubin is associated with three icons of modernist architecture. The first is the Tropical House, designed by Jean Prouvé after the Second World War for France’s colonies in Africa. Even though these prefabricated, easily transportable buildings were intended to be mass produced, only three prototypes were ever built and delivered to their colonial destinations. In 1999 Rubin arranged to have them moved from Niamey and Brazzaville to France. He restored one and donated it to the Centre Pompidou ten years ago.

Richard Buckminster Fuller, Fly’s Eye Dome. Toulouse, 2013. Photo: Mark Lyon

The second architectural icon is the Fly’s Eye Dome by the American visionary Richard Buckminster Fuller, created in 1965 as a prototype for low-cost, portable housing of the future. Rubin owns the largest of these buildings (architect Norman Foster, who worked on the project with Fuller, owns another prototype). Rubin bought the house in 2013, restored it and first exhibited it at the Toulouse Contemporary Art Festival. From the very beginning, his plan has been to make the futuristic construction with 61 glass “eyes” as an object of inspiration and study for students of architecture and design.

And, since 2005, Rubin and his wife, Stéphane, have owned the Maison de Verre in Paris. The 1932 masterpiece by French architect Pierre Chareau was originally built as a combined home and office space for a well-known Parisian gynaecologist. Some might invoke Le Corbusier’s famous phrase, “machine for living”, to describe it, but Rubin prefers to describe it as a vivid example of “poetic functionalism” (the term was first used by Swiss architectural historian Bruno Reichlin to describe the work of Prouvé, Chareau, and, later, Piano). As one can imagine, preparing and learning to live in it has been one of the biggest (and most time-consuming) projects in Rubin's life.

In the 1990s, when he was still working on Wall Street, Rubin also acquired the legendary Bridgehampton Race Circuit, a storied automobile racetrack on Long Island in New York known as “The Bridge”. Closed by local authorities as the area developed, Rubin turned the former racetrack into one of the most unusual golf clubs in the world but kept its sporting name. Architect Roger Ferris designed the clubhouse, which doubles as a home for Rubin's extensive collection of art. American artist Richard Prince is a member of the club and a golfing buddy of Rubin’s. The Bridge doubles as a platform for various multi-disciplinary cultural projects, which have included a dance performance choreographed by Robert Wilson created especially for the space, a Captain Beefheart cover band fronted by Nona Hendryx, and the world premiere of a film by installation artists Jonah Freeman and Justin Lowe with live music by the Psychic Ills.

Jean Prouvé's Tropical House at the Centre Pompidou, Paris, 2007. Photo: Mark Lyon

Rubin is also a curator of art exhibitions. For example, he co-wrote the catalogue for the Centre Pompidou’s exhibition Jean Prouvé: Tropical House. At the Museum of the Moving Image in New York City he curated Walkers: Hollywood Afterlives in Art and Artifact, a 2016 exhibition featuring the work of 40 contemporary artists who use images and materials culled from the cinema. He also curated the Richard Prince: American Prayer exhibition at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, which hosted another one of Rubin's exhibitions, Avedon's France: Old World, New Look, which explored the well-known American photographer's relationship with France.

In addition, Rubin is the author of countless essays and several books. About a month before this interview, he sent me some reading material – altogether around 600 pages. That, he said, would help me to prepare for the interview. Among the materials were a PDF version (complete with the author's corrections) of the catalogue for the Avedon's France exhibition, which had not yet been published in English, as well as an essay for an upcoming exhibition catalogue about Pierre Chareau’s life in America, an article he wrote for Art in America about the architectural historian Reyner Banham (1922–1988), an essay about Richard Avedon and Allen Ginsberg for a Gagosian Gallery catalogue, a text from Cahiers d’Art devoted to Alexander Calder's legendary residence in the French town of Saché, essays about Richard Prince, and articles by a few other authors, including interviews with Rubin and enthusiastic artworld reviews of the Walkers exhibition. After reading all of that, I felt like I had already known Rubin forever. But this made our actual meeting even more surreal.

I met Rubin on December 1st at the Maison de Verre in Paris. After ringing the doorbell (the building is located in a courtyard, hidden from curious passersby), the first thing I encountered was a tour group in front of the glass-tiled façade so often seen in photographs. The house is open once a week to guided tours consisting of architects and architectural students. As Rubin admitted to me later, he usually tries to avoid being at home on those days. And I, for my part, suddenly felt a bit more privileged as I walked past the tour group.

Our conversation took part in the kitchen, the long metal table covered in manuscripts, Avedon's photographs and books about Chareau. Rubin wore a simple, comfortably worn, sandy-coloured knit sweater and lambswool slippers. He drank several cups of coffee during my visit, which lasted about two hours. And my previously prepared list of questions turned out to be almost unnecessary – it felt as inappropriate to interrupt his flow of thoughts as it would to stop an excellent film during its most interesting scene.

I left the Maison de Verre with another small pile of reading material. Now, as I write this, the hefty catalogue to the Walkers exhibition lies open next to me on my desk. And this conversation, although it has formally ended, is actually a process that continues.

Avedon's France: Old World, New Look exhibition at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France (October 18, 2016 - February 26, 2017) Photo: David Paul Carr/BnF

Yesterday I went to see the Avedon exhibition at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France for a second time. There weren't many people there, and I got to look at it quite closely. I am most fascinated by the detail in the exhibition. For example, how you've pinned pages from Avedon’s book on Jacques-Henri Lartigue, and Avedon's own photographs on plinths, with both sides of the images visible....

Those pictures, which are actually engraver’s proofs, were exhibited at Jeu de Paume in 2008, but then they were just hung on the wall without showing the backsides. It wasn't until the book Richard Avedon: Made in France (2001) was published by Jeffrey Fraenkel that those pictures, the double-sidedness, came out. I have always been interested in the idea of double-sided works of art. Richard Prince did many double-sided works that he put on a plinth. Several were in American Prayer. You had to walk around to get the whole picture. In the case of Avedon, it’s more about revealing the process: how an image becomes something to manipulate into a magazine layout, then a book, then a jumbo exhibition print and so on.

Avedon's France: Old World, New Look exhibition at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France (October 18, 2016 - February 26, 2017) Photo: David Paul Carr/BnF

I once visited the German art collector Egidio Marzona at his home, and we also talked a lot about these other sides of artwork. One wall of his studio is covered in paintings, and when students come to see his archive, he takes the paintings down one by one and shows them the backsides – often that's where the whole history of the work can be found. The Avedon exhibition confirmed again what I've read about you – that you've always been interested in stories. Also this house, where we're having this conversation today, is a story. Tell me how your story with collecting first started.

I think that collectors are born, not made. In fact, I think that collecting is some deep-seated sickness – a glitch in your genetic code. As a human being you are subordinated to this desire to accumulate and classify. In my early days as a collector there was also this idea of completion, which has since disappeared in my mind. There’s no such thing, once you get beyond basic stuff like coins or baseball cards. I was collecting every baseball card available for every team each season. For a little kid, it was an ambitious goal, realised one five-cent bubble gum pack of cards at a time, then trading with your classmates. There were gambling games you could play with your friends in the schoolyard at recess to win more cards. Today you just go on the internet. It’s all there. Condition-rated, packaged in protective plastic. Boom. Have a question? Google it. No secret knowledge, no fun.

I suppose that was at a very early age.

Yes. I was seven or eight. I also collected comic books. My mother wouldn't let me buy them or even have them in the house. I accumulated this clandestine collection of comic books, which I kept at a friend's house. I collected coins, and I collected stamps – I had these blue binders filled with pennies, Roosevelt dimes, Mercury dimes, Buffalo nickels, from the days of real silver coins.*

Later on, that knowledge came in handy. When I was trading precious metals, one challenge was to anticipate a discount relative to the price of silver that these coins would have as the price of silver went up. I was buying 55-gallon drums full of these coins that aggregators collected for me. Guys who would check into a motel room in the middle of nowhere and place an ad in the local paper. People were selling their dimes to this guy for two dollars each, when in fact they were worth even more melted into bullion. I was shipping tons of this stuff to Europe and melting it down. I had morphed from numismatist – combing through my father’s pocket change every day – to arbitrageur.

The price of silver collapsed in 1979. And the day it started, I woke up in the middle of the night – a light bulb went off in my head, so to speak – and I called the refineries in Belgium, France and Spain where we were melting all these coins and told them to stop the furnaces. I got on a plane and I flew over there, and I said I will pay you the cost of refining, but you are not going to refine what’s left, I’m shipping it all back. They thought I was nuts and giving them free money. Because I knew that once the price of silver collapsed to four, five dollars an ounce, these things would be worth more intact than melted. I was playing the arbitrage between the collector value and the commodity value as the price rose and fell. I even came up against a very interesting conundrum. We had bought these Nazi-era German coins with swastikas on them that people had been hoarding, and those came back, too. They would sell for the premium again, but since I'm a nice Jewish boy, I thought that we have to send the coins back again and have them melted, because we can't be part of this. So we sent them back. In the current environment, I’m sure their collector value is rising...unfortunately, because it reflects a warped political environment.

But, returning to the beginnings of my career as a collector – stamps were a big thing. I was fascinated by the fact that my hero Franklin Roosevelt was an avid stamp collector, and I loved stamps from exotic places like the Belgian Congo – shades of Heart of Darkness. But, like any boy who had grown up in a lower-middle-class neighbourhood, cars were IT.

Was that in New York?

That was in suburban New Jersey. The boys in my neighbourhood, they all dropped out of high school, but they lived at home long enough to buy a car. They worked at gas stations and garages, mostly. On weekends, I watched the cool guys with pompadours and cigarette packs rolled up in the sleeves of their t-shirts polishing their Corvettes and Pontiac GTOs. I was genetically hard-wired into American automobile culture.

When I finally had enough money, I bought a Jensen-Healey, which is an awful English sports car. This was before I understood the distinction between the car as appliance and the car as toy. A Jensen-Healey is a toy, not an appliance. I commuted to work in it, but it was a nightmare. The car broke down all the time. The best you could say about it was it was a rare thing. Because nobody wanted one. It was a complete piece of shit, the electrical parts didn't work, etc.

Ferrari LMB #4453SA, 1964. Courtesy of Robert Rubin

The next year, when I got a much bigger bonus, I decided I was going to buy a used Ferrari. This was right after Ferrari was sold to Fiat. At that time even just seeing a Ferrari on the road was a big deal. Now every fucking dentist with a midlife crisis has a supercar of some sort. There are Ferrari gift shops in airports. But back then there were very few Ferraris in America. It was a real confidential world. I subscribed to this mimeographed market letter where people listed their Ferraris for sale.

I would travel all over America on weekends to see potential cars. Finally I plunked down 45 grand to buy a 275 GTB. That led to meeting a guy who worked only on Ferraris. One day he comes to me saying: “There’s a guy selling five cars, all Ferraris. If you buy them, we can resell four of them and you’ll end up with the car you want for free.” The car I wanted was called a Ferrari California Spyder Short Wheel Base, which today is around ten million dollars, but at that time it was something like a quarter mil. I bought the car, and the Ferrari mechanic restored it...to within an inch of its life. It looked like a goddamned Christmas tree. Its patina was destroyed, its soul was gone. It was a new car.

So I put it up for sale, and I got an inquiry from a guy in Texas who had a Ferrari, a 330 LMB, which was the four-litre version of the Ferrari 250 GTO that all billionaires buy today. He said, “Would you like to trade up and give me the Cal Spyder plus some cash?” And I said yes. Now I’m really in the game. I have a tier-one competition Ferrari to rally and race. Of course, this was before these cars became financial instruments. Back then most people involved in old cars were racing them as obsolete competition cars, weekend warriors and gearheads. It was a cult, not a fashion.

I soon grasped one of the main rules of collecting: the more you buy and the more people are satisfied with the way you conduct yourself, the more things will be offered to you first. The classification – the taxonomy – of old race cars was just starting at that time. The networks were just evolving. In the 1970s no one wrote about cars with what I would call an art historical approach – to consider that each car had a specific identity and provenance: a serial number, a racing history that could be documented through photographic and archival records of competitions. A car can be treated the same way as a painting, sold by this dealer to this collector, then at auction and so on. But with cars it is more complicated. Cars are not as discrete as paintings, because you can change the engine, you can change the suspension, the body and so on. It’s the chassis that determines the identity of a car, but a lot can happen along the way. Also, if you look at the factory archives, which is something I like to do, the teams moving the cars around were doing a lot of falsifying of the customs documents, so they could use an old car’s customs carnet for a new car name instead of paying again for a new carnet. Just change the chassis plate. There were a lot of these fiddles. And, as the collecting hobby developed, you often found two or sometimes even three people claiming that they have the same car, especially crashed cars, because one guy has the engine and four suspension corners, another guy has half of the chassis, etc. Lost cars were turning up but they were fakes. You really had to be on your toes.

The other thing that was very exciting about it all was that when Formula 1 and sports racing teams set up the schedule, the last races of the season always were in Australia, Africa and South America. So that they could sell the works (factory) cars to the locals, knowing that the following season they would be uncompetitive race cars in the capitals of Europe. So, there was kind of a diaspora of all these great Formula 1 cars in the Third World to go and find. I did a lot of these deals myself. I bought cars in South Africa and Brazil, for example. A friend of mine pulled a Maserati 300S out of Angola!

Bugatti s/n 57248. Grand Prix Graphics. Photo – Bob Dunsmore. Courtesy of Robert Rubin

These transactions often involved having tea with the widow of the driver and so on. I bought a very famous Bugatti from the illegitimate son of King Leopold II of Belgium, whose father had taken the car as collateral from Bugatti for a loan that Bugatti never paid. They were all great stories, and the cars were very beautiful, very original. I also learned that it was often necessary to give a car as partial payment to somebody in order to help him get over the so-called psychological hump when parting with his baby, so I had cars I referred to as “baseball cards”, meaning to be traded at a later date in my quest for the next grail.

I had my eyes on a Ferrari GTO, and Jess Pourret, the first person to write a chassis-by-chassis book on GTOs had one that I sensed he would ultimately sell. He was living in France but wanted to expatriate to Asia. He had helped me with the questions I had about Ferraris, and thanks to him I had the confidence to make some savvy acquisitions. I bought a very famous Ferrari from a guy who was a postman in Cupertino, California, before Apple made Cupertino famous. The place was a backwater at that time, and he was advertising this car as the winner of the 1952 Mille Miglia race. I asked Jess if the car was real. He said, “Yes! Go look at it, and you can see where Ferrari welded over a competition gas cap and took all the competition stuff off of the car so that they could pretend it was a new car and sell it as a road car to some unsuspecting rich guy.” I asked why are people not understanding this? He said, because this guy is a fucking postman in Cupertino – who’s going to believe him, right? So I went to see the car, and I bought it. And I restored it back to its competition configuration. The word got around that I was buying everything legitimate. I set up a shop in Southampton and had a full-time mechanic. I was always looking for cars. I bought stuff, I traded stuff, fixed them up and raced them at vintage race meets. I had a great time. I even anticipated the car Jess would want in part trade when he sold his treasured GTO. I found it, bought it, and put it away. A few years later, we did a deal.

In the 1990s there was an auction in France of furniture made by Ettore Bugatti. When Bugatti first moved to Molsheim, he made some very special pieces, including a pasta machine constructed entirely from Bugatti car parts, which I bought somewhere else. Very Dada in spirit. I was outbid by other people for pieces I wanted. But there also happened to be several pieces by Pierre Chareau at the auction. They were made of metal, they had this great industrial look. I bought a couple. I had always been fascinated with artisan entrepreneurs – Ferrari, sure, but especially the Maserati brothers. They were pursuing this passion under great duress, straddling the divide between the artisanal and the industrial to create functional objects of intense beauty. But I gradually lost interest in cars and turned to another group of artisan entrepreneurs: Prouvé, Fuller, even Chareau.

.jpg)

Maserati 250F #2524, 1956. Grand Prix Graphics. Photo – Bob Dunsmore. Courtesy of Robert Rubin

And then you turned your attention towards design?

From Chareau, it was a short hop to Prouvé. I should add that my father was a mechanic. He reconditioned old appliances, like air conditioners, refrigerators and televisions, and sold them. He had a service company named A1, and when it went bankrupt, he got a job working in maintenance for RCA Whirlpool. He was one of these guys who went from house to house fixing your washing machine, wearing a nice clean uniform and bow tie, but he kept a workshop in the basement of our house. He and I built model train layouts down there together, too. A real man cave. My mother was hell-bent on preventing me from following in my father's footsteps. Getting my hands dirty was a forbidden thing in our household. I was going to be a doctor, a lawyer, an accountant, whatever nice Jewish boys become. So, I feel that by pursuing these things with mechanical elements I am honouring my father, but, by doing it at the level I'm doing it at, I’m also honouring my mother. I do sometimes get my hands dirty, but I’m mostly directing other people. Making the choices. There’s not necessarily a “scientific” answer to how to restore or resurrect something. What you do with this house, for example, is a political choice. Do you make it into a museum, do you live in it, do you use it to represent a luxury brand? I mean, these are all choices, and, even if you don't touch the house at all, you’re still saying something about what it was designed for versus what’s possible in the 21st century....

At the core of all this is definitely my negotiation through this parental conflict. So, my mother was happy that I’m rich enough to buy this stuff, and my father is happy because I’m honouring vocational skills. At one point I funded a vocational school in Israel and had it named after my father. There are too many people out there with useless bachelor degrees who should go out and learn how to fix something, how to make stuff. Unfortunately, society doesn't value that.

The Prouvé thing got interesting when I started buying stuff from a guy who was a master chineur. That’s French for “finder” or “picker”. In the beginning it was furniture, and then one day he said, “Listen, there are these tropical houses in Brazzaville (which I had read about) that have been denuded of their furniture by a French dealer. They took everything of value, but the houses are still there. Shall we get them?” The rest, as they say, is history.

Jean Prouvé, Tropical House. Niamey, Niger, 2005. Photo: Mark Lyon

Was the condition of the houses really as bad as was reported somewhere?

No, apart from a few bullet holes and some cuts for air conditioners, the houses were OK. They were made of aluminium. The wooden parts had rotted away, but the aluminium parts and the steel parts were all fine. In fact, they were saved by having many coats of paint over the years. I financed it. He went down to Africa to oversee the operation. He liked to present himself as Indiana Jones hacking through the jungle in search of lost modernist masterpieces. In fact, the houses were in the middle of downtown Brazzaville, but we all make our own myths, don’t we?

Unlike your automobile period, this time you didn’t go to Congo yourself?

No, I never went to Brazzaville. I figured that there was probably stuff that had to be done that was better done by someone else. Let’s leave it at that.

There were three houses, right?

Yes. Two that were built in Brazzaville with a connecting walkway. They were constructed as the residence of the representative of the company that was marketing the industrial system. And there was one earlier building in Niamey. I was interested in rebuilding one house as a polemical gesture against what I saw as the fetishisation of Prouvé, the decontextualisation of Prouvé. I mean, Prouvé was all about social housing, solving problems of homelessness, allowing France to humanely house its population. And now Prouvé is...well, people are buying 100,000-dollar tables to put under their Basquiat, or even million-dollar tables – because some of them are quite expensive. It’s an odd post-colonial gesture, don’t you think? It never occurred to me that the house would have a real financial value. Obviously, the dealers didn't think so, either, because they took the furniture and left the house. But I thought it would be an interesting exercise. Soon after I bought the house, I cashed out of my business, so suddenly I had time on my hands.

Did you decide to quit Wall Street?

I was essentially fired. But I was fired with what they call a golden handshake. I didn't mind. Let's put it this way – I lost a power struggle. They said, “Look, it’s you or him, and he’s worth more to us, so what’ll it take to buy you out of your contract?” The answer was, fortunately, a lot.

Afterwards, I said to myself – I’m only 47 years old, why not go back to school, my life could use some structure to keep me off the streets. I had already done that once. I had gone back to school in 1989 for 18 months and got a master’s degree in modern European history. I needed a break. But I went back to work after that. This time I knew I was not going back to work.

So, I started to study architecture seriously. I passed my orals on 150 years of French architecture (1830–1980) and fifty years of Austro-German architecture (1889–1939). I taught the history of architecture required course to masters students, which is like teaching ornithology to birds – they don’t really give a shit about the history of architecture, because they’re interested in the future of architecture – their future in architecture – and they don't understand that there’s a connection between the two.

You gave your Tropical House to the Centre Pompidou. What happened with the other two houses?

One house was sold by my former partner at Christie’s for five million dollars. It was purchased by André Balazs to use as a VIP room at the Raleigh Hotel in Miami. Then reality set in. Somebody explained the hurricane-related building codes of Florida to him, and the project got too complicated. He decided to leave the house in its containers. He’s had it in storage since he bought it. The third house still belongs to my former partner, and I imagine that one day he will sell it.

You know, the big problem with Jean Prouvé – as with everything today – is faking the stuff. There’s a lot of that going around, and lots of flying writs among furniture dealers. And of course, that’s a big, big problem in the art world. Takes all the pleasure out of collecting. Your radar has to be on Defcon 4 at all times. That’s no fun.

For example, I used to collect handmade pre-World War I Marklin steam trains. I had an enormous collection that I bought through two or three people I trusted who specialised in this stuff. And in my garage, where I also kept my cars, I had a big room with those beautiful Marklin trains all set up. A step up from the Lionel layouts I used to make with my Dad. In fact, I can show you. I still have one of the station houses with beautiful handpainted details here in the Maison de Verre. Something I bought turned out to be fake, and I looked into it further and learned that at some point in the 1970s Marklin was in such parlous financial condition that one day when they were approached by a guy who wanted to buy all the original moulds and forms from before the First World War, which were sitting in some storage room and gathering dust, they said yes! Sold him everything. Times were hard in the toy train business, I guess.

The guy set up a factory somewhere, bought stocks of old tin and old lead-based paint and started making stuff. He was extremely clever about it. When the Berlin Wall fell, he went all around Eastern Europe partnering up with people who would then walk into a shop in London with this thing wrapped in old paper and say, you know, my grandfather had this, he gave it to my father, we hid it from the Communists...like salting the gold mine, building a plausible backstory. And who could have anticipated this? It’s very hard to identify a fake made of period materials on period machines. I was so unhappy that I consigned my entire collection to Sotheby's. That was more than 25 years ago. There were a few hundred lots, and everything sold except for six or seven lots...which were the fakes (laughs). But I was happy to get out of it, because it was no fun anymore.

Just like collecting contemporary art now is no fun, because it's too expensive and all the people talk about is money. It undermines the creativity of artists, because they have this enormous financial incentive just to make stuff and decorate people's houses. They regress as risk-taking artists. It's the same if you look at cars today – the fun is gone, in the sense of discovery, the archaeology of it, the sense of belonging to a club or secret society or whatever. Also in the sense of learning something, and in the sense of creating meaning by assembling things. It’s all marketing, positioning, value creation...yeesh.

This goes back to what I was talking about, trophy checklist collecting. Initially the collector says: “Oh, I need to have one of these, one of these and one of these. I need to have all the New York Yankees from the 1967 season, or all the Roosevelt dimes – one each of everything.” That’s a basic collecting impulse. Collecting contemporary art has become simplified in the same way. It used to be a matter of personal taste, now people who are collecting art, they’re too busy to develop any personal connoisseurship, so they have an art adviser, and art advisers have an incentive to put you into art that will immediately appreciate in value, art that has a liquid and transparent market and art that makes them look good. No art adviser is going to say to you, “This painter is not very highly thought of, but if you like it, you should buy it. Who knows how things will shake out in ten or twenty years.” They’re always going to steer you in the direction of artists that they also get something back from. They’re saying to the artist that they've got an eager collector, and they’re saying to the collector that they've got an in to the artist. So, they’re creating this parasitic, capitalist intermediary between the collector and the artist. Dealers at least have to invest in their artists, to commit capital to the enterprise. Art advisors just pick off opportunities and dumb down the market.

Richard Prince: American Prayer exhibition at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France (March 29, 2011 - June 26, 2011). Photo: Copyright Pascal Lafay/BnF

Take Richard Prince. The typical “blue chip” art advisor says, “You need a Cowboy, a Nurse and a monochromatic joke painting, and then we can move on to the next trophy artist.” It destroys any sense of the breadth and depth of his work.

It's very unfair to compare Richard with Jeff Koons, Takashi Murakami or Damien Hirst, because he’s not looking to create a brand, a global brand. Quite the opposite: he makes art for himself. I have in my book collection some correspondence between Philip Roth and a fellow writer friend, Edward Hoagland. Roth tells Hoagland he’s going to send him the galleys of his next novel and that Hoagland should tell him what he really thinks. Roth’s not asking for a blurb for the dust jacket. He writes: “What six or seven people think of a book is really all that counts. The rest is how I make my living.” Substitute art for fiction, and that’s Richard to a “T”.

But it’s happened for him – in some way he has nonetheless become a brand. Why?

Richard is an artist who has never been afraid to change things up. He’s produced so much different stuff. He wakes up and he says to himself, time to try something new. He’s fearless that way. And that’s one of the things that I admire about him. But that lends itself to checklist speculation. Not only does he change it up all the time – thereby making many discrete categories of art – but he’s also very prolific, he doesn't do much of anything except make art and read. He’s completely antisocial. He plays golf, but other than that he’s a complete homebody. He’s an obsessive artist. Lastly, the images that he appropriates – which were transgressive and marginal and uncomfortable when he appropriated them – have been assimilated into the American cultural mainstream so that what was once threatening is now a badge of cool. All of the above makes his art a ripe asset class, as the finance boys say.

Take the Cowboys, the appropriated Marlboro ads with the Reagan era cancer irony and all that stuff. Those are beautiful pictures without any subtext. They have wall power. Or the Girlfriends. All that motorcycle iconography that was so out there in the eighties is what young hedge fund guys like right now, it’s cool right now.

Along come the people from Wall Street, from hedge funds, who have transformed art collecting into a portfolio exercise. There are people who own more than a hundred Richard Princes, stacked in vaults like gold bullion. That's why Prince had this moment of violent appreciation. When he was selling handwritten jokes for ten dollars each he certainly wasn’t thinking about getting rich. He was without a dealer for part of the eighties. The financialisation of his work came later, it was imposed on it retroactively, and it made a quick buck for a lot of people. That’s why he’s a darling of the art advisers...you, too, can hit the jackpot and have good taste in the bargain. Same with Ed Ruscha. You couldn’t give that stuff away until the new millennium. Now, if you want a Ruscha, take a ticket. The line’s around the block. Artists like these went from being artists’ artists to having sacks of cash falling out of the sky on them.

Richard Prince: American Prayer exhibition at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France (March 29, 2011 - June 26, 2011). Photo: Copyright Pascal Lafay/BnF

But, to be honest, in the middle of all that Richard Prince also did this fashion thing with Louis Vuitton, sending his nurses onto the runway for Spring/Summer 2008.

That was a one-off. He’s hardly been a fixture on the runway since then. Wasn’t his finest hour. But listen, he’s entitled to make money now. Until his fifties, he could barely rub two nickels together. He’s used that money to amass the most interesting collection of twentieth-century books, manuscripts and ephemera in America. It’s so conceptual and personal. The linkages and associations create whole new layers of meaning. When I stand in his library, I know I am in Prince’s. That’s the test for me. Most collectors’ homes are trophy checklist assemblages. Best of. Greatest hits. You could be in a high-end hotel with themed suites except for the decorating budget. With Richard I don’t have to check his ID.

Do you think the exhibition you did based on his collection of rare books somehow changed the view on Richard Prince as a personality and as an artist, because it went deeper?

I call it my appropriationist biography of the artist. I think it explained the sources of his art to a broader public. It worked on a superficial level – hey, look at all this cool Beathippiepunk stuff – but it also elaborated the sources of his art. Many people did tell me after the show that it made Prince's work more understandable. Because there were fifteen vitrines of stuff from his collection, and the walls were hung with art that came out of that. In contemporary art installations typically you decontextualise the art – you put it in a white cube. My curatorial process is different. I’m not trying to reinforce an existing canon, I’m much more of an unpacker.

Richard Prince: American Prayer exhibition at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France (March 29, 2011 - June 26, 2011). Photo: Copyright Pascal Lafay/BnF

I read that shortly before its opening Prince said in an interview, “It will be a strange exhibition. No one will go see it (because of the location).”

Right. But, you know, the fact that it was only seen by 20,000 people is just fine. Besides, the catalogue is something that will live on. I saw someone reading American Prayer on a subway the other day. Richard loved American Prayer. So did the people whose opinions I care about.

Most exhibitions start with the idea of the exhibition – the catalogue comes after, and it's just about the exhibition. I like to start with the catalogue. I had no idea what American Prayer would look like when I began my research. I gave myself a year to do it, and the installation came out of that process. The catalogue overlaps with the show, but it’s not simply the catalogue of a show.

Avedon's France: Old World, New Look exhibition at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France (October 18, 2016 - February 26, 2017) Photo: David Paul Carr/BnF

I found very interesting the angle you used to look at Richard Avedon. During his lifetime he struggled with not being accepted by the art world. He was talented, famous and rich. But he was an outsider. Now he’s regarded as a genius. That's something you normally do not find when reading about Avedon.

No, but that’s because he was trying to impose his own narrative, to force people to see his work a certain way, instead of just putting it out there. Like, you know, I’m really a great and serious artist, forget my fashion stuff, it’s how I pay the bills.... And it's crazy, because what makes Avedon brilliant as an artist is this very hybridity in his work, the quality of being many different things at once, to manipulate the same images across diverse media. But he was so desperate to be enshrined in the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) that he fucked himself.** At the same time he wanted to be the most famous photographer in the world, to simultaneously have the succès d’estime and popular success of say, a Stanley Kubrick. Easier to do that in film than in the art world, though, especially in photography, which in Avedon’s time was like a ghetto of the art world, struggling to be recognised as a “fine art”. Such a quaint expression these days, don’t you think?

Do you think if he had lived ten years longer, he could have succeeded with an exhibition at MoMA or not?

If he had lived long enough for the most recent changing of the guard at MoMA, probably. The new curator, Quentin Bajac, gets it. Avedon had a pretty great exhibition at the Metropolitan in 2002, but I’m shocked at how superficial most people's take on Avedon still is. Even with In the American West (published in 1985 – Ed.), the pictures of his father, the portrait series The Family for Rolling Stone and the big murals – notably Warhol’s Factory and Allen Ginsberg’s family – he is still suspect. As time goes on his image will evolve, because he’s not around to interfere with it anymore...to tell you what to think about his work. In this regard I’ll tell you a cautionary tale.

Avedon initially had a good relationship with John Szarkowski, the MoMA curator who was calling the shots in the photography world back in the sixties. Szarkowski was putting together his book Looking at Photographs, and he wanted to publish Avedon’s most famous photograph, Dovima With Elephants (1955). Avedon wrote to Szarkowski and asked him to substitute one of his “art portraits” (they ended up using his picture of Isak Dinesen), which Avedon thought more representative of his work. I got the sense from reading the correspondence that this irritated Szarkowski – who’s the curator here? Now, fast forward nearly half a century later. Time magazine does its issue of the 100 most influential photographs of the twentieth century. Richard Prince’s Cowboy – the one on the cover of the Whitney catalogue of his 1994 retrospective, the first photograph to make a million dollars at auction – was one. Guess which Avedon photograph the magazine picked? Dovima. If Avedon were still alive, he would be lobbying the editors of Time to use one of his “serious” images and agonising over the whole thing. For what? Dovima is a great image.

Avedon's France: Old World, New Look exhibition at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France (October 18, 2016 - February 26, 2017) Photo: David Paul Carr/BnF

It's ironic, because I see Avedon as a postmodernist who wanted to be recognised as a high modernist, to be in the canon of the great artists he grew up worshipping. But he was not able to take that final step to postmodernism. He was arguing, correctly, that photography, all photographic images, are constructed images, in opposition to the idea of the decisive moment of Henri Cartier-Bresson, and Garry Winogrand's street photography, which had more currency in highbrow circles. If Avedon really went to the end of his thinking, he would have embraced the “pictures generation”.*** He did make some constructed images toward the end of his career, like the great Volpi Ball**** series, which are collages with the collaging effects hidden. But he was too invested in the craft of photography, because he had been brought up as a working photographer. He took passport pictures for the Merchant Marine, he was involved with the Famous Photographers School***** in the 1960s.... He just couldn't make the next step, which is to say, if photography is only constructed moments, why can't they just be fake? He was still stuck at the level of constructing photographic moments when Cindy Sherman and Richard Prince came along. Prince’s thing was “I'm only going to take photographs of photographs.” Cindy's thing was to make film stills for films that never existed. Everybody had their own angle on “pictures”. Some of Avedon’s photo-narratives come close to that but aren’t that. He couldn't, because he was a photographer with a mission to elevate his craft to the level of art. Prince could, because he wasn't really a photographer in the first place.

One way to understand this is to compare Prince’s Cowboys to Avedon’s In the American West. Both series – Avedon’s are photographs, Prince’s photographs of photographs – concern the Western myth, and both were made in the Reagan era, with significant political overtones. Avedon jettisoned the whole concept of landscape – something central to the whole idea of the West – and took photographs of people at the margins against white paper backgrounds in natural light. They are among the most beautifully made and imposing portraits you’ll ever see, minimalist and expressionist at the same time. Prince does the same thing, by re-photographing photographs that were made with some of the technical proficiency – but not the genius – of Avedon’s. Avedon is pushing photography to its limits of scale, contrast, etc., while Prince is pulling the rug out from under it. But they’re working the same territory.

And that, in some way, was Avedon's tragedy?

Ironically, Richard Prince was making art out of Avedon's commercial work – one of his Fashion images is rephotographed from an ad Avedon shot. The “picture generation” stuff is deadpan, it’s like telling a joke, but there’s no laugh track. Avedon was not able to see how close he was. In the 1993 Carnegie Triennial, his Berlin Wall photos were there with Sugimoto, Williams, etc., and he fit right in, as a conceptual artist who happened to work in photography – as Christopher Williams describes himself – rather than a “fine art photographer” like Irving Penn. He was getting there, he just missed it by a generation or so.

People often ask me how I went from Richard Prince to Richard Avedon. You know what I really hate in life? When you buy something on the web and it says “you might also like...” and then they offer you all this other obviously related stuff. I have a writer friend who every time she buys a book on Amazon, one of her novels is recommended to her.... I’m trying to short-circuit all of that. I like to go from one subject to another on the basis of very idiosyncratic or ethereal connections. In this particular case I got to Richard Avedon because of the Avedon Foundation – John, his son, had read American Prayer. He loved the book and, as at that time they were putting together a big show that included the mural of Allen Ginsberg's family at the Gagosian Gallery, he asked me to write about Ginsberg and Avedon.

That means that through it all you also discovered Avedon from a different angle?

I found the angle on Ginsberg, and through that I realised that Avedon was fascinated by Ginsberg's relationship to his father. Which led me to look into his relationship with John and his own father, Jacob. It also has a lot to do with Robert Frank, who taught Ginsberg how to take pictures. I found that Ginsberg's picture taking is much more interesting than I understood it to be. And Frank was the guy who Avedon thought was his main competition.

Installation view from Walkers: Hollywood Afterlives in Art and Artifact (November 7, 2015 – April 10, 2016). Photo: Thanassi Karageorgiou

Last year another aspect of your passion for collecting – cinema – materialised in the form of an exhibition. How did that come about?

I was always interested in movies. When I was at Yale, I was a director of the college film society. I kept one of the group’s 16mm projectors in my room when we weren’t using it, and sometimes I watched the same movie three or four times during the day before screening it at night. I took classes in cinema, and I wanted to transfer out of Yale and go to the UCLA film school. My parents thought I was joking – they weren't going to stand aside and watch me abandon the Ivy League for what they thought of as a trade school. My father told me, “Take the needle out of your arm, son.” Later on, when I become a newspaper reporter (that was my first job after college and before Wall Street), I got to review movies for the paper. I wanted to be a writer, but I went off in another direction.

Installation view from Walkers: Hollywood Afterlives in Art and Artifact (November 7, 2015 – April 10, 2016). Photo: Thanassi Karageorgiou

At some point, I started to collect objects related to the cinema. I only wanted things that preceded the completion of a movie, stuff related to process, to making rather than marketing. So, scripts in particular. And the further away the script was from the final shooting script, the more interesting it was to me. Final shooting scripts are interesting documents, but the earlier drafts, with handwriting all over them, are much more interesting. The other thing that I collect is set photography. Pictures that are taken on set while a movie is being filmed. The coolest of them all are continuity photographs, which are taken of the empty sets so they can be recreated exactly if they have to go back and shoot. At this point I probably have a thousand scripts and a few thousand set photographs. I specialise in three areas: film noir, Westerns and New Hollywood. By New Hollywood I mean Monte Hellman, Dennis Hopper, all those little movies of the 1970s up through David Lynch. Scripts have a lot of textual stuff and the photographs – which are much higher resolution than screen grabs off the movie print – have a lot of visual stuff that one of the artists in Walkers calls “exformation”. I love that concept. That’s what I’m always looking for. Exformation: the stuff that doesn't make it to the final product. The outtakes. The path not taken. The stuff that falls of the back of the truck in the way to a scheduled delivery.

Installation view from Walkers: Hollywood Afterlives in Art and Artifact (November 7, 2015 – April 10, 2016). Photo: Thanassi Karageorgiou

Where do you find all this stuff?

Well, there are regular auctions of Hollywood memorabilia, there’s a network of pickers, and at least one reputable dealer. A lot of material comes from the estates of actors and producers – a box of scripts turns up in somebody’s dead uncle’s closet.

Is there lots of competition?

Yes. For example, The Godfather, The Wizard of Oz, Gone with the Wind, Casablanca – the big Hollywood movies, those materials are fetish objects. I am not so much interested in fetish objects as I am in creating a body of work that can be studied over a long, long period of time about how movies get written and made. I have four or five different versions of Touch of Evil (1958), full of Orson Welles’ handwriting all over them. I have an early draft of The Searchers (1956), where at the bottom of the last page is a question mark after the words “rides away?” They didn't even know while they were shooting the movie how they were going to end it – does John Wayne stay or leave?

Installation view from Walkers: Hollywood Afterlives in Art and Artifact (November 7, 2015 – April 10, 2016). Photo: Thanassi Karageorgiou

Do you feel this is also your responsibility, as a collector, to keep these things from dispersion?

Yes, absolutely. And I also work on a bigger level, where there are enormous archives that are not necessarily interesting to me but which should find an academic home. So that they stay together. I’m warehousing a few large archives which will end up in research institutions. The priceless material from Hollywood films can have an archival value and a fetish value. There was an auction at Bonhams yesterday, and the dress Kim Novak wore in Vertigo sold for 23,000 dollars plus commission. No interest to me. But I love the movie. I’ve got the script, lotsa set photos and art department set drawings for the staircase in the bell tower.

What did you buy yesterday?

I bought a set of three scripts by William Faulkner. I bought three copies of different versions of a script for a movie that never got made. I love scripts by great writers for movies that never got made – they're great. I also bought Michael Curtiz's working copy of Angels with Dirty Faces (1938), for which I already own five drafts from different stages of it. Forty years ago, when I was just starting out as a newspaper reporter, I interviewed Sidney Kingsley, who wrote Dead End, the stage play on which it was based. Then I bought four different, relatively obscure film noir scripts from the 1940s, two of them by Curtiz. And I bought a copy of Rosemary's Baby with a letter from John Cassavetes and a huge archive of The Godfather: Part II sold by the art director. It comes with the script, location photos, etc. That was more expensive.

Were there other bidders for this stuff, too?

Yes. These auctions, like yesterday’s, happen maybe half a dozen times a year. People in the industry collect this stuff.

How did you feel afterwards, when the auction was over and you got all this? Happy, satisfied, pleased?

I felt like I’m making progress. I got them all for pretty reasonable prices.

At the same auction they also had, for example, Maureen O'Hara's personal copy of How Green Was My Valley (1941), which was given to her by John Ford. I don't know what it went for, but it was estimated at 60,000–80,000 dollars. I have no interest in that, because I don't learn anything from it. You can probably find a copy of the final shooting script of How Green Was My Valley online. But I’m looking for the stuff that isn't online. I try to go down the black holes. Because if I don’t do this, nobody else will. It meets all my personal criteria; it’s something that’s ongoing. I can look at stuff virtually every day. I’m constructing meaning by the choices I make in assembling this. I hate the word “curator”. “Curated” restaurant menus and stores – that’s nauseating. Actually, I recently did a show in New York with Glenn O'Brien at Storefront for Art and Architecture, where we made a slideshow of art that was unsold at that week’s auctions, threw in a few “ringers” for good measure, and we did a comedy routine as each picture came up. Like, “How is Donald Trump going to decorate the White house?” and then we put up George Bush’s portrait of Putin, and we put in other artists that are easy to make fun of. We called the show Not Curated, because I think the whole thing with the word “curate” is silly. It’s like “iconic”. Linguistic inflation has sucked all the specific meaning from it.

But you can maybe try to change it?

Then I have to come up with a better word. “Art traffic controller”. How about that?

I guess I think I'm a curator when I curate an exhibition in a museum or a gallery, and the rest of the time I'm something else. A hoarder, an accumulator, or a safeguarder, I don’t know. But what I do know is that you don't curate a collection...even if some collectors have curators who choose for them and take care of the works. It seems to me that curation has to do with an assemblage of works along a theme – monographic or subjective – at a specific moment in time. Curating one's own (or someone else's collection) is essentially a money management or an inventory management exercise (laughs).

Pierre Chareau. Maison de Verre (1932). Paris, 2016. Photo: Mark Lyon

Returning to this house, this is already your tenth year living in the Maison de Verre. Are there still any mysteries left to solve, or can you now say that you understand the house completely?

No, it's still ongoing. What's amazing is how we keep finding things. Just a month ago we had reason to open up the ceiling in the bathroom and the master bedroom. And we found – and nobody ever knew before – that among the many experiments undertaken in this house was a kind of prototype of radiant heating. Because the ceiling was laced with wires that had very thick cloth around them, and they clearly thought that if they could heat wires, then the heat would radiate down and would warm up the bedroom. In fact, what happened was that the wires burned out. It wasn't successful, but it showed you the way in which the construction of this house was relentlessly experimental.

Six months ago somebody walked in with seventeen glass negatives of the house under construction. Which, of course, I bought on the spot. I looked into them, and I found out that Pierre Chareau had commissioned these photographs to take them to Brussels and project them as part of the installation he was working on. But that didn't happen. The records of this house are not very complete in comparison to, for example, Le Corbusier, who kept almost everything. He was nuts. Let me give you an example.

When I was doing research at Le Corbusier and on his relationship with Jawaharlal Nehru, I found in his Foundation’s archive a file containing various Christmas cards that Nehru had sent to Le Corbusier over the years. None of them were personally inscribed, they were essentially form letters masquerading as holiday cards. Nehru must have sent out hundreds if not thousands of them every year – he was the Prime Minister of India, for Christ’s sake. Le Corbusier had kept every one of them, because that's the kind of guy he was. Therefore they still exist. Chareau, on the other hand, packed a suitcase and left Paris in a hurry with the Nazis on his heels. So, whatever there was is gone. There are no plans for this house left, very limited documentation, just some pre-construction plans in the archives of the city of Paris.

This house is a lifetime project. You buy a picture, you hang it on a wall, and a year from now you need money or you're bored with it, and you send it to Sotheby's and you start over. You can't do that with a house.

It's very interesting to see what happens to all these mid-century modernist houses in California, where anything goes. What happens is – rich people buy them, and then they expand them tremendously. They essentially add another house to it, so that the original house has become an appendix to some bigger project. You can't do that here. You have to leave all the stuff the way it is. I can fix things, but I could not wake up one morning and say, “Let's put in a steam room.” You have to live in this house without the kind of amenities that people expect at a certain level of net worth. Second of all, it's an ongoing restoration – there’s a lot of stuff that needs to be done, and we do it, virtually every day. I mean, I’m not really making a sacrifice. Yes, I’m sacrificing the potential steam room, but we get to live in this great house in the middle of Paris in utter calm, great light, with a fantastic garden. Can’t complain.

This morning, before our conversation, I met with Diane Venet, the art collector and wife of French sculptor Bernar Venet. She told me that she was born near this house and was here twenty years ago. Back then, this house reminded her of the Eiffel Tower. Le Corbusier, for his part, called it a “machine for living”.

I don’t think he was referring to the Maison de Verre; I think he was talking about his own houses. Le Corbusier's houses are more sculptural than functional. In Le Corbusier's case he called the shots and more or less imposed on the resident the rules for furniture, art, etc. This house, on the other hand, was an intense collaboration between the family and the architect. And I think, unlike Le Corbusier, who brings an a priori sense of architectural style to his every project, Pierre Chareau is part of a tradition that I would call “poetic functionalists”. These are people who don't work in a particular architectural style, but rather extrude its style from the project itself, by addressing the problems of programme. And so this house doesn't have a particular style. Prouvé doesn't have a particular style. Paul Nelson, who is also part of the same group, doesn’t have a particular style. Renzo Piano is an heir of that tradition. Also Shigeru Ban, Richard Rogers. Richard Meier is more like Le Corbusier. You can spot one of his buildings a mile away. Prouvé never used to say that something was beau (“beautiful” in French) – he would only say that it was bien (“good”), because he was opposed to the idea of saying something is beautiful for beauty’s sake. It had to work. Everything in this house (except the radiant heat in the ceiling) works.

One of the least nice things that can happen with art as a collection object is that it ends up in someone’s storage room and never sees the light of day. That's almost impossible with architecture. But I think the responsibility of someone who buys and sells architectural masterpieces is even higher. What’s it like to collect architecture?

I don't really collect architecture. I’m a serial occupier of architecture. I occupied the Maison de Verre, I occupied the Tropicale house, I occupied Buckminster Fuller's Fly's Eye Dome. But the difference is that the Dome and the Tropicale house are, at the end of the day, pedagogical objects. They are potentially nomadic architectural installations. The Maison de Verre is a different proposition, because it’s a real home, and in three years, when our son graduates from high school, we’re going to live here full-time.

Up till now, we have been living here in the Maison de Verre as in a pied-à-terre. Sounds a little pretentious, but it’s taken a good ten years with this house to bring it up to being a habitable residence. It was visitable but not habitable. Now it’s habitable, and we live here. That requires a different level of attention, and I can assure you that I'm not in the market for any other modernist masterpieces any time soon. You can imagine all the propositions I get. Every structure that’s in danger of being torn down. I even get letters from real estate agents in France saying, “Since you are the owner of the Maison de Verre, maybe you would be interested in this other modernist masterpiece?”

There are projects in architecture that I’m interested in, projects I can participate in, like the beautiful Chareau show at the Jewish Museum curated by my friend Esther da Costa Meyer. But for the moment we’re in, let’s call it a digestive pause. No doubt the house will suggest many projects to us over the next twenty years if we listen carefully.

What else could I tell you about this house?

Maybe you could show it to me now?

Sure.

Robert M. Rubin. Photo: Thanassi Karageorgiou

* Between 1946 and 1964 Roosevelt dimes in the United States contained 90% silver and 10% copper and weighed 2.50 grams. “Silver standard” denotes a monetary system in which the standard economic unit of account is a fixed weight of silver.

** In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Richard Avedon worked closely with John Szarkowski on a project for MoMA, tentatively titled Hard Times, which was never realised. He remained bitter for decades after, because other photographers had monographic exhibitions there, but never Avedon.

*** The Pictures Generation was a group of artists in the 1970s influenced by minimalist and conceptual art. By manipulating with familiar images, they demonstrated how those images influence and change our views about the world. Among the artists represented in the group were Richard Prince, Cindy Sherman, Barbara Kruger, Robert Longo and others.

**** The Volpi Ball was first organised by Count Giuseppe Volpi di Misurata in 1932 in honour of the inauguration of the Venice International Film Festival. It took place in the count’s ornate 16th-century Palazzo Volpi and has gone down in history as the last aristocratic ball in Europe, or the indulgence of a lost era. An invitation to the Volpi Ball was one of the most coveted in the world. The Volpi Ball took place until the late 1980s and ceased along with the passing of its most illustrious personalities. Avedon commemorated the last ball with La Bal Volpi par Richard Avedon (1992), a series prepared specially for Egoïste magazine.

*****The Famous Photographers School (FPS) was established in 1961 in Westport, Connecticut, and was inspired by the financially successful Famous Artists School correspondence course begun soon after the Second World War. FPS was founded by the photographer Victor Keppler (1904–1987) and existed until 1974. The core of the school consisted of ten leading photographers of their day, including Richard Avedon, Philippe Halsman, Irving Penn, Bert Stern and Alfred Eisenstaedt. Thousands of students learned photography through the correspondence course these instructors created.