“Travelling is better than arriving”

An interview with Turkish art collector Agah Uğur

08/01/2018

It is often said that an art collection mirrors its collector. If so, Turkish art collector Agah Uğur’s collection is at once his mirror and mouthpiece. Charismatic, provocative, socially acerbic, distinctly focused, stimulating thought and discussion – it is oriented towards action and participation instead of passive reflection and escapism. At its foundation are all the “sore points” in contemporary society: power and the abuse of it, women’s rights, issues of ethnic and religious identity, social engineering. The majority of the artwork in the collection was made after the year 2000; the artists are from Turkey and the Middle East as well as North and South America. The focus is on new media, although percentage-wise video art makes up the largest part of the collection. It is also undeniably Turkey’s largest and strongest collection in the video art niche. “I think video is a great media for expressing difficult concepts in a very dynamic story-telling way,” he says.

Uğur is the CEO of Borusan Group, one of Turkey’s largest industrial manufacturing groups. In addition to his personal collection, he is also involved in the management of Borusan’s corporate collection, the Borusan Contemporary Art Collection. It is located in the company’s headquarters, a masterpiece of early-20th-century architecture that has been carefully restored and is now a stylish nine-story office building. As the work week comes to a close, the employees clear away their desks, and at the weekends the impressive building turns into a museum of contemporary art. All of the rooms, including Uğur’s office, are then opened to the public. Such an office-museum concept is the first of its kind in Turkey. Borusan Group is also the founder of the Borusan Istanbul Philharmonic Orchestra and an active supporter of cultural life in Turkey. Uğur himself is one of the co-founders and vice chairman of SAHA, Turkey’s contemporary art support foundation. “I do not like to do things without sharing,” he says. “The philosophy of living better is sharing.” \

The living room in the house. The digital work above the balcony doors is “Day” by Cevdet Erek. The orange banner on the fireplace (not used anymore) is by James Richards. Photo: courtesy by Agah Uğur

For this interview, I was Uğur’s guest for two days, and our conversations took place in a variety of locations: beginning on the terrace of the Borusan Group headquarters with a view across the Bosphorus, continuing in his project space, and finally at his home. The project space, called “Why Not”, is located in a residential district on the outskirts of Istanbul and is actually a regular apartment turned into a home for art. Uğur acquired the apartment more than a decade ago as an investment. His mother lived there for a year, until “one day I was having a cup of coffee here, and I was thinking that there are so many walls in this apartment, why don’t I turn this into an art space type of thing.” And that’s exactly what he did. Even though the expositions here regularly change, “Why Not” is a home for some of the most socially and politically acerbic works in Uğur’s collection.

In fact, the original layout of the apartment has been preserved, but all of the furniture has been removed and replaced entirely by art. Some works of art even occupy a whole room, for example, the installation by Istanbul-based Armenian artist Hera Büyüktaşciyan, which consists of a thousand pieces of soap. “This is actually about the memory of the Armenian culture, which is slipping away like soap. The smell was so strong for the first two years, that the window was open all the time,” laughs Uğur. However, “Why Not” is not open to the public. It is mostly Uğur’s guests who see it – art professionals and others interested in contemporary art.

A view of the dining room. The plates are by Estonian artist Marko Mäetamm. Photo: courtesy by Agah Uğur

When our conversation continues at Uğur’s home – on a hillside terrace surrounded on all sides by pine trees – for a brief moment I feel like I’m in Scandinavia, not Istanbul. This house is one of the most unusual art collector’s houses I’ve ever had the honour of visiting. Instead of paintings, there are screens on the walls. Screens of all sizes, and in all of the rooms. When I arrive, they’re all turned on and each shows a work of video art. A neon installation is “running” over the door to the terrace. It’s not like this every day, Uğur reassures me with a laugh. He turned them all on just for me.

But the strangest thing is that, unlike what I had imagined (because I had already read about his house), the flashing, moving images all around us do not make for cacophony. Just the opposite – they give the house a kind of unusual liveliness and vitality. It seems to pulsate of its own accord, it vibrates with stories, visual experiences, thoughts, and episodes. Later, Uğur will tell me that the biggest problem most collectors of video art have is that they do not know how to exhibit the art. Uğur has solved this problem – he lives at the centre of his collection and its narratives, surrounded by conversations, questions and art that provokes conceptual discourse.

This work by Füsun Onur, one of the most senior conceptual artists in Turkey, has been a part of Documenta 13. Photo: courtesy by Agah Uğur

According to psychologists, most people experience a greater or lesser existential crisis every ten years or so. I’ve heard that you had just such a crisis in relation to collecting art.

My wife and I collected paintings for ten years. We mostly bought them at auctions, because the gallery system in Turkey was still very primitive at that time. There were no Western-style galleries in Turkey, except maybe one or two. I mean, where the gallery represents an artist and cares about his future, tries to expose him to the outside world, and sets out on a journey together with the artist. Of course, there were galleries in Turkey and they hosted exhibitions, but the exhibitions mostly only featured work by locally known artists, and when works were sold, the galleries got their commissions and organised the next artist’s exhibition.

When I decided to stop buying paintings in late 2007, we had accumulated about 60 works in our collection at the time. Mostly from well-known, living Turkish artists. But I realised that that wasn’t for me, and that if I continued doing it, I’d be just a typical, average collector. True, when I made this decision, I didn’t know what to do anymore, I became kind of lost. I wanted to continue my relationship with art but in a more engaged way. But I didn’t know where to start.

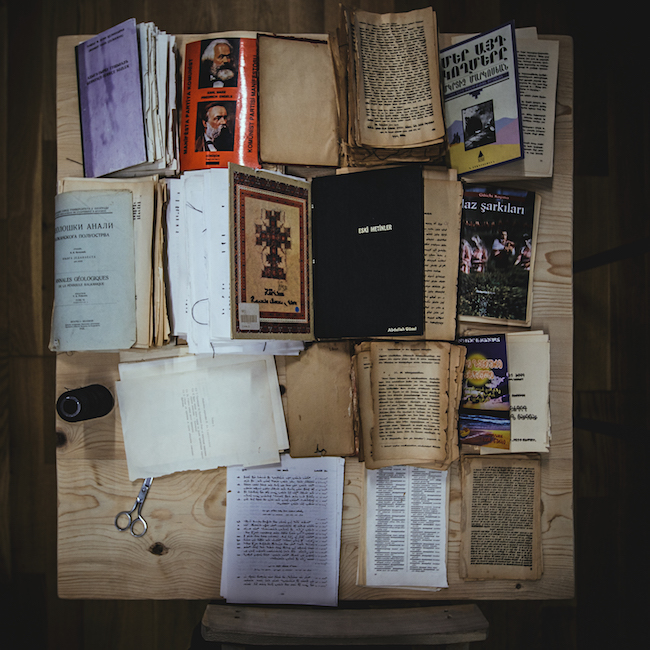

Didem Erk’s work called “Anomalistic” consists of nine books written in languages not officially recognised by their countries. Each word in these nine books is sewn in black yarn. Photo: courtesy by Agah Uğur

So, you stopped collecting because you realised that painting as a medium no longer addressed you, or were there other reasons?

I think there were two or three reasons combined, and I made my decision in a single day, at an auction.

First of all, I think I had probably matured on my journey as a collector and grown out of abstract paintings. When you start a journey, you don’t have much money, you don’t have much knowledge. Maybe you’re just married, you’re trying to make your home beautiful, so you buy paintings mostly for decorative purposes. It’s an easy choice when you are young. You prefer abstract to figurative. That went on for, like, ten years.

Buying art needs a bit of initial courage, but once you’re beyond that, it gets easier. And then you need the next challenge, such as some paintings from more well-known artists. And then you go for even more important works; you want paintings from the artists’ earlier years, but without knowing whether they’re masterpieces, whether they have any special meaning. You do it just for the adrenaline, for the opportunity. You have names on your list, and you try to get them. After ten years, I said that contemporary art is more than paintings by local artists.

Secondly, I started questioning the specialness, the uniqueness of the type of artwork we were collecting.

The auction scene changed around that time, too. Auctions in Turkey have always been elitist – mostly about old art by the masters, for rich people, for established collectors. But there was this new auction house, called Beyaz Müzayede, which opened in 2006, and it democratised the auction system. Suddenly more and more people were interested in art, a new crowd emerged from almost nowhere, and artwork was selling for more reasonable prices. So it was easier for people to buy, and it also shed light on the sheer numbers of similar works made by the same artists.

I began to wonder whether this art had a special voice and was it something for the future. For me, the answer to both of these questions was “no”.

The third reason was probably the combination of market conditions, prices and what I saw at that specific auction.

That day I had gone there a bit early and was just sitting there and looking at the people. The people with whom I would soon compete with for artwork. I came to see two distinct types of people. Either the wealthy Istanbul families or the financial sector speculators who have found a new platform to play in. There were quite a few of them in the auction room that day – all male, in their mid-30s, very self-assured and loud people, if you see what I mean. Both profiles are difficult to compete with if you’re work with a budget. And at that auction I said to myself, “No, I’ve grown out of this, these works of art don’t resonate with me so much anymore, I’m questioning their genuineness and their standing in the future, and I’m also questioning who I’m competing with.” Those were enough reasons to stop, and I have never been to an auction in Turkey since. Nowadays, when I go to New York, I sometimes go to an auction for fun. I don’t buy anything, but it’s good to be there.

My wife later sold almost all of our old collection of abstract paintings, and fairly successfully at that. We kept a few paintings and drawings that I still like.

Ali Kazma’s well-known video work “The Clerk”. Photo: courtesy by Agah Uğur

Looking back, do you think you had at least a couple of works in your collection that could be considered masterpieces?

No, I don’t think so. When you are not experienced and you are not very much engaged with artists, you generally have a great difficulty in identifying their special works. Also, I had very little contact with the artists, this was not so easy. They were generally more distant to art lovers and collectors. Finally, I didn’t have a support system, like advisors, fellow collectors or trusted gallery owners. I really value this support system now.

My relationship with the artists whose works are in the current collection now is much closer. Actually, I treasure these relationships. We have many dinners at home with the artists. We eat together, we laugh together, and I learn from them. As you know, artists are very clever people, and I appreciate that. They look on what is happening in society from a different perspective. So, this element of my journey in art gives me great pleasure.

But how did that begin? You stopped buying paintings, you were confused for a while, and then you radically changed your focus?

When I stopped buying paintings, I didn’t know where to start a new journey. At that stage a few of the younger-generation collectors, who had been collecting new media work for some time, were very instrumental in my new path. Through them I learned how to research. I started reading a lot. Questioning more deeply the artwork in the exhibitions I go to also became a habit.

I think a statement by an international collector I read in a book also became a reference point for me. It said: “Don’t choose artists; choose galleries first.” For most collectors this statement can be very questionable, but honestly it helped me in the early part of my new focus on new media works.

Through this quote I came to understand that there were four or five very progressive galleries in Istanbul, mostly owned and managed by idealistic, well-educated women in their mid-30s. They had these portfolios of very interesting artists who impressed me immediately.

Most of this new generation of mid-career Turkish artists started producing works in this millennium. They are extremely socially engaged, politically oriented and, just as importantly, they create art from deeply thought ideas and projects. This level of obsessive focus really intrigues me. Because of their genuine approaches, they have strong international careers and are invited to biennials, museum shows, residencies. Now they form one of the backbones of my collection.

Over time, I also became close to a senior group of conceptual Turkish artists who were also socially engaged and in whose art political criticism played an important role. They started their careers in Turkey’s turbulent times, in the 1980s and 1990s. In those days, the treatment of liberties by the state was very tight, and these more established conceptual new media artists became a silent voice for a better world.

I guess this was also a good reason why they achieved recognition in the international arena before they did so on the Turkish art scene. This group of senior Turkish artists form another backbone of my collection.

Finally I have always been very socially engaged, trying to do something for society. Over the years I have been on multiple boards of non-governmental organisations involved in business ethics, the environment, women’s issues and the like. So when I discovered this type of art in my new path, it was a natural extension – actually, a beautiful extension of what I already cared for.

Inci Eviner’s work titled “Parliament” in the library room. Photo: courtesy by Agah Uğur

What is it that draws you to video art? Is it the narrative?

Yes, the storytelling. I feel that I’m a storyteller myself. When you lead a business, you have to create a compelling story for the future to excite and inspire people. So, it comes naturally to me.

Have you understood why you have this need to surround yourself with art?

Did you want to ask whether it’s a form of escape, or fleeing from something?

Not quite. It could also be inspiration.

No, for me it’s really not an escape. It’s more like an inspiration. I like the expression “travelling is better than arriving”. I read it somewhere when I was studying at university. I think most of the things I do in life are with a long-term view but not to prespecified destinations. I know, for example, that in business I’ll have to retire at some stage, but I probably won’t realise that the day of my retirement has come until the very last day. I think that my art journey is the same way.

People sometimes ask me, “When will the collection end, and what do you want to do with it?” I don’t even want to ask that question to myself, because I’m constantly on a journey. Seeing, learning, talking about art, buying it, supporting it – in short, being in it in an engaged way is the journey. For example, I was very excited this morning that you were coming to meet me and we were going to talk about art. The collection itself is like the photographs from a great holiday. It’s full of pleasant memories. Of course, the collection also brings a sense of pride. After all, who doesn’t like being praised for something important to him or her?

I think art makes people feel different, it influences their mood. Even for people who are not so engaged with art it gives comfort. But in addition to this pleasant feeling, I also get inspiration from the artists and the art they produce. I like to be challenged by new ideas, or seeing existing issues being challenged in a very interesting and aesthetic way. It’s always good to have this mental exercise with somebody who creates something very effectively. That’s one thing. And the second thing is the relationship with living artists. Artists are mostly at the forefront of society, and it’s great to be there with them. On the other hand, I have to say that, even though I have good relations with most artists, I don’t buy artwork from them directly if there is a gallery involved.

Gökçe Çabadan’s painting of 3 street boys of Istanbul. Photo: courtesy by Agah Uğur

Is it important for you that the system is maintained?

Yes. Number one, because the system needs to survive. Number two, it’s not that easy to talk money with artists. But sometimes there are artists who are not represented by a gallery, and then I have no choice. I usually say that I can offer them such-and-such an amount, and whether they accept it or not is their decision, so there’s no bargaining or negotiation. In a way, I feel a bit privileged that I am by the side of an artist during his or her career, together with some other key collectors. Instead of being anxious about their financial issues, the artists can concentrate more on the art. So, it’s an interesting feeling I have, a good feeling that they know that there are people like me. It’s kind of like a child who knows that the family home is always there to return to.

What do you think is the main responsibility of an art collector? Especially during a time like this, when the market bubble is so big. Consumption is growing, and so is the amount of art on the market, and there’s more and more worry about art losing its quality.

I don’t feel that collectors have a responsibility to support art by continuing to buy and thereby create demand. Collectors buy art because they want to and they have to, if they are obsessive enough. However, some collectors go beyond the practice of collecting and find clever ways, alone or collectively, to support art, especially younger artists and the production of art. In a way, they become patrons, and this is different than collecting. Of course, I have a great deal of admiration for this type of new-generation art patrons.

Also the art market is both too complex and large on the one hand and too concentrated on the other. Winner takes all has become the norm. 90% of the value of the artwork sold at the major fairs and auctions is made by maybe 200 artists. How about the remaining one million artists in the world? How are they going to continue to motivate themselves for the future? Collectors are one element of the system. The remaining part – states, institutions, patrons, the public, galleries and the like – must also play their role for an overall change to take place. I find this collective wisdom and responsibility very important for art not to end up being perceived only as glossy products exhibited in the art fairs. But, of course, all this effort will not change the reality that, at the end of the day, one has to accept that only good art will survive to the next generations.

Do you have a mission in your collection?

Yes, very much so. I sometimes make speeches at family business conferences about the institutionalisation of family businesses. I say to them that first you have to define the goal of your business. I say that if the purpose of owning a business is just to make yourself and your family rich, you don’t need to be institutionalised and professional. You just make the money and then go do something else. Like a hunter – just go and hunt things. But if your purpose is to actually create an organisation that you will be proud of other than just for making money, with a hope that it will survive after you, then you have to institutionalise.

What is institutionalisation? It means having a focus and discipline and creating enough systems to be able to repeat success. If you don’t have a system, you cannot repeat your success. So, coming from this background, I hold the same strong belief and attitude towards my art collection.

I’ve come to a point where I feel the collection itself is separate from me, and I have a responsibility towards it, just like the type of business owner I am referring to. I am responsible for the collection to achieve its mission, not my own personal mission. Therefore, I’ve separated myself from it.

And what is this mission?

After a part of my collection together with works from two other collectors were exhibited in 2015 at Salt, a major space in Istanbul headed by Vasif Kortun, the top art person in Turkey, and learning that 90,000 people visited the exhibition, I felt like I had graduated from school. I wanted to step back and ask myself what’s next. In the end, I wrote down a one-page policy statement, a manifesto, about where I want to go and what this collection’s mission is – the collection’s mission, not my own personal one.

Interesting, that one of the two goals in this document is: “To document with a critical view the socio-political movements at the start of the millennium in Turkey and in other similar countries. On specific themes: use/abuse of power, social engineering, gender issues, cultural, ethnic, religious identities.” A few years ago, when I interviewed American art collector Daniel Wolf in New York, he said that nowadays the collector is the main critic.

I completely agree. If you are sensitive towards the society’s need and if you are open-minded enough to see and collect powerful art on social issues, you end up being a critic yourself. For example, there is so much social engineering going on around the world. Societies become less tolerant to differences. Of course, this is a hopeless effort, but on the way a lot of tensions are created and bad things happen.

In a sense, I criticise this societal and political change for the worse through art’s powerful lens.

The entrance of Why Not. Photo: courtesy by Agah Uğur

Do you think that art is in some way able to influence society? For example, in Turkey today – does art have a voice?

Art definitely has a voice, but if you’re asking me whether art can change the overall situation we have today, then probably not. On the other hand, art can definitely help us to better understand what’s happening right now and likely to happen in the future. I think art can help a paradigm shift take place on a personal level, and every such individual transformation is valuable for overall change. On the other hand, art cannot as yet influence or change the masses.

Some of the pillars of your art collection are provocative and significant works of art by Turkish and other artists. It seems that the provocative aspect is very important for you.

I like to challenge things. I don’t like comfort zones. I have grown into a change leader. I think it is only normal that this aspect of mine is also reflected in my art collecting practice. I think that provocation, if used properly, is great – it’s not as bad as it sounds. It changes things. It’s a powerful agent of change.

You’ve been collecting video art for more than ten years now. Do you think that the market for it has changed? For example, there are only a few works of video art at the big art fairs.

Very few. When I go to art fairs, there’s hardly any video art. On the other hand, when I go to biennials, cutting-edge exhibitions, maybe 30% of the work there is video. So it’s a dilemma. Artists definitely want to produce video work, especially in emerging countries, where the storytelling concept is more necessary to make social and political issues easier to understand and more colourful. So, I think that as long as artists want to continue making videos, video art will continue to live. But it will continue to be acquired mostly by institutions, because institutions feel that they have to do it, more like an obligation rather than a choice. At least that’s the impression I’ve gotten. There are not enough individuals who collect video art, and usually those who collect are seen as interesting, risk-taking people.

Banu Cennetoğlu’s work titled “Swiss Newspaper” at Why Not. It shows all the newspapers published in Switzerland in one specific day. Photo: courtesy by Agah Uğur

In what sense? It would seem that video art is easier to collect – you don’t need huge warehouses to house it. So, theoretically speaking, there ought to be more collectors of it.

Yes, but I think the main reason is that, first of all, they don’t know how to exhibit it. Because if you buy a work of video art, nobody imagines that it can be done like in my house to have a lot of monitors around you. Even established collectors have a whole roll of videos for one screen, and when one finishes, the next one starts. I don’t like that, I think that it’s unfair to the previous work. So, in short I think the potential collectors are still not comfortable about how they could show video art.

And secondly, because they don’t know how safe it is in terms of copying. People often ask me what happens if you copy the USB. I can copy it a thousand times, but it doesn’t matter – there’s a certificate, there’s a contract, there’s a history of that work. And so far, over the past ten years, I haven’t seen any video-art fraud, which is spectacularly different than the fraud that goes on with paintings, for example. I haven’t heard of any video-art fraud, but there’s so much of it for paintings, which is theoretically much more difficult to do.

But, because people don’t appreciate video art as much, there’s not enough market demand. I think the main concern for people like us, for collectors, is the value of the art, and not the art’s physical future or fraud. I don’t mean value as in making money out of it, but to have the feeling that – apart from the joy and pleasure you get from owning that art – that your decisions have been the right ones and that the art will preserve its value. In the back of your mind, even though you’re not going to sell it, you know that the value is still there.

And, because the second-hand market for video is not there, this is the main problem. As far as I can guess, if there are, say, 10,000 works of video art – starting from the most important, like Bruce Nauman, down to some young Turkish artist – I don’t know how many of them are completely sold out and have started changing hands on the second-hand market. Maybe 1% or 2% at best. So, there’s still a long way to go if you’re thinking as an investor. Even if you’re not an investor with the goal of making money, that urge, that economic value is nevertheless important to you, and I think it’s difficult to spend money on video art. It’s not only about trying to make money out of it, but it’s the concept that whatever I buy should at least keep its value. But the risk is too high. I think this is the reason why there are so few collectors of video art.

A view of Why Not. The banner in the corridor is by Canan, the top feminist artist in Turkey. Photo: courtesy by Agah Uğur

At the same time, though, the value of a work of art is a very irrational thing. Especially in today’s market conditions.

I agree. It is scary, like many things in life, the references in the pricing of art is lost. The lid for the high end of the art market is wide open due to the irrationality of easy and new money on the one hand and speculation on the other hand. Of course, this affects the lower-priced segments of the market, too. It’s worrying for the future of art. Only the top artists and intermediaries win in this system. Room for collectors with a passion is taken over by collectors with money and ambition.

It seems that collecting video art is a time-consuming process, too. Considering that some videos are 40 minutes long or longer.

Yes, it is, but I guess social media and internet have made it easier. Video art has become within reach whereever you are in the world. I work with some galleries outside Turkey, and they can easily show me videos that they believe I will be interested in. Also, if I see an interesting work from an artist I didn’t know before, I can easily reach his or her other works on the web and learn much more about him or her. I accept that video works take a longer time to review, but that’s a part of the research and discovery, and I love discovery. It takes a few months for me to make a purchase decision. First, I try to learn a lot about the artist and somehow, within this time, the work matures in me. So the length of the video work is a tiny part of my overall process.

Halil Altındere’s 80-kg marble work titled “Boxing Bag”. Art not only gives pleasure but also pain. Photo: courtesy by Agah Uğur

Does that mean you never make impulsive purchases?

I can easily be classified as a risk-taker, but I rarely make impulsive choices in art. I’ve trained to restrain myself. Sometimes, if a work of art is very appealing, affordable and its artist is young, I can go out of my way and make purchases more impulsively. But, as I said, this happens quite seldom. I need the research, that’s the fun part.

Do you have a certain budget that you reserve for art?

Yes, I have a yearly budget.

Is it a strict budget? That is, do you always stay within your budget?

Over the past nine years, I think maybe two years I went over my budget. The rest of the years I was almost in line. I have two responsibilities fighting with each other: a responsibility towards helping the collection reach its mission, and a responsibility to stay within the budget. At any one time I generally have a mental shopping list of eight to ten works of art, and they stay on that list for a few months. Then maybe suddenly two months later, I go and try to acquire three or four of them in one go.

Wall drawing by Ahmet Ögüt at Why Not. Photo: courtesy by Agah Uğur

You can afford to think for a long time, because there’s not that much competition in the video-art market.

Yes, it is an advantage. If I don’t make a decision now, I know I have about a two-year safety period to really think about whether I want this work of art in the collection. Sometimes people are surprised if I go to a gallery and say, “No, this is too much for me, I cannot buy it,” even though I like it. Then two years later I go back and renegotiate for a price I can afford. I believe that I am not being unfair here. Because sometimes I feel that price positioning of works are not done realistically.

Price positioning is another topic, because we come from a business society, and so the pricing has to be precise. Because there is so much competition, and if you overdo it or underdo it, there’s always a problem. Either you don’t make a profit, or you don’t sell. But in the art world, especially in emerging countries like Turkey, when there was this relative boom, prices for young artists’ work also increased. But they became overpriced, and then it was a disaster for an artist to accept a lower price. Both of these situations are bad. Either your work doesn’t sell but you desperately need it to sell (because, apart from your own pride, you need to pay the bills), or you reduce the price, but that’s also an unwanted situation, because the value of your work goes down.

Just one example: some time ago I noticed in a gallery a piece by a well-known Turkish artist. She is over 70 now, she’s taken part in key exhibitions including the Venice Biennale, and it was a really important work, I could feel that. She did it back in 1995. We were now in 2017, and the art was still there in the gallery. I told the gallerist that there’s something wrong here. We are either overdoing her reputation and she doesn’t deserve this, which is definitely not true. Or you’re not promoting her properly, or you priced the work wrong. You always have to ask these questions. I mean, if I was on the commercial side of art, I could have transformed it in a big way – it’s just elementary business knowledge.

Maybe that’s your next challenge?

No, definitely not.

Halil Altındere’s historic work “Dance with Taboos II” made for the 5th Istanbul Biennial in 1997. Photo: courtesy by Agah Uğur

Returning to your mission as a collector and the mission of the collection itself. As a Turkish art collector, is it within your powers to help local artists become seen on the international scene?

I don’t do these things as a private person; we do them through the SAHA association. That’s an organisation that we initiated and founded with a group of like-minded people in 2011. Its goal is to support Turkish contemporary art, both locally and at the international level. Most of SAHA’s members are local collectors and people who are interested in art, but also businesses who own corporate collections. We started out with nine friends, and now SAHA has almost 100 members. Our members are great people, and all are proud of how SAHA supports Turkish contemporary art.

Initially, one of the inspirations for SAHA was Outset in London, but we operate differently. We never work directly with the artists; we work with significant international art organisations. It might be MoMA in New York, Documenta, the Venice Biennale, Tate Modern, etc. For example, if they choose a Turkish artist for one of their exhibitions, SAHA covers all or a part of the production costs for that work of art. This concept has worked very well, and SAHA now has a wonderful reputation globally.

We are currently also thinking about establishing a residency program of our own in order to help younger artists to benefit from SAHA’s ecosystem.

Video work by Koki Tanaka titled “A Haircut by 9 Hairdressers at Once (Second Attempt)” at Why Not, exhibited in the Japanese Pavillon at the 55th Venice Biennale in 2013.

And the last question. Considering the large number of videos you’ve seen and owned, and the very diverse narratives in them, how often do you still experience a real moment of artistic surprise? A genuine moment of true authenticity?

Good question. Not as much as before.

Actually, I think there are two parts to my answer. One of them is the idea that the concept itself is still extremely important to me, and, if an idea is interesting, it catches me. I value this part as the more authentic aspect for me. The second part is how the story is told, how subtly it’s done, and so on. I look for deeper and deeper ways of explaining. And the more intricate a work is, the more artistic surprise I experience.

For example, Heba Y. Amin’s video As Birds Flying (2016), which could be seen just now at the 15th Istanbul Biennial and is one of the newest works in my collection. When I read the story, it seemed interesting to me, and when I saw the video itself, I liked it even without the accompanying story. Do you know it? It’s based on a story that was in the media in 2013 about an Egyptian fisherman who had noticed a migrating stork with a electronic receiver attached to its leg, and he notified the authorities about it. The receiver was recording the bird’s migratory route, but the Egyptian authorities considered the stork to be a foreign spy.

The newspapers wrote that the stork might be a British or Russian spy. And I thought that the subtext of this story was very significant, very important. It brings to mind the manipulations by those in power and the social engineering we’ve been talking about.

This fear and paranoia, this condition of the soul that is consciously cultivated at the state level, it is killing the free spirit in many nations.

Like I said before, the most important thing for me is the message and the way in which it is constructed and presented. I guess I’ve matured enough – I don’t fly like a moth to a flame anymore, so to say.

Agah Uğur. Photo: courtesy by Agah Uğur