Post-Soviet Anamnesis

Soviet-era Architecture, Design and Art, as Seen Today

12/02/2013

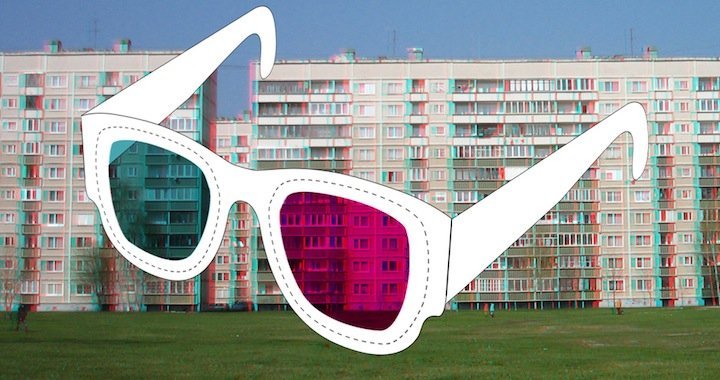

After more than 20 years, people's interest has returned to the territory that lies behind what was once called the Iron Curtain – specifically, interest in the art and architecture that was created during the Cold War. For example, the American magazine e-flux has already covered, in two consecutive issues, the theme of conceptual art in Eastern European countries during the period of the soviet regime. “The history of conceptual art in the West has been systematized, while we in the East have practically nothing,” is how Zdenka Badovinaca, director of Ljubljana's Modern Gallery, begins our discussion. How does one explain this current interest? Maybe enough time has passed for a reexamination of values to have occurred, and the soviet legacy can now be looked upon from a cool distance. It also seems that along with the death of Oscar Niemeyer, modernism now officially belongs to the past. Another possible reason is the exact opposite of the one just mentioned: now is our final chance to write down this “unknown history” – before the memories and testimonies of the people who experienced it, as well as what is still left of soviet culture itself, crumble to dust.

Through 25 February, the Vienna Architecture Centeris exhibiting “Soviet Modernism (1955-1991). Unknown Stories”, which is the result of a several-year-long study on architecture in 14 former soviet republics, excluding Russia. Included in the show are countries in the Baltic, Central Asian, and Caucusus regions, as well as Eastern Europe. However, right here in Riga's Latvian Museum of Architecture, there is an exhibition going on (through 1 March) that is dedicated to the work of Latvian architect Lia-Asta Knāķe (1928). At the center of the show's attention is the building that houses the administrative offices of the state energy concern, Latvenergo, on Pulkveža Brieža Street; having received both praise and criticism, the structure is often called an example of ugly soviet architecture.

Upon becoming aware that oblivion was fast on their the heels, the creators of the Vienna project, which was originally planned to be just an exhibition on the architecture of Armenia, were motivated to expand their scope to well over a dozen former soviet countries. “The putting together of the project was a very long process, and during it, our assumptions and prejudices came to change,” says Katharina Ritter, one of the three curators of the “Soviet Modernism (1955-1991). Unknown Stories” exhibition, during a conversation with Arterritory.com. “One of the greatest benefits of the project was the opportunity to meet with state architects, urban planners and mayors; we even met with the former First Secretary of Kirghistan. Without these discussions, the project wouldn't have been as rich and diverse as it is. It is important to note, however, that personal and subjective oral information doesn't always reflect the way things “really happened”, but it definitely does enrich it. That sort of information can't be found in any publications, especially in those that came out during the period under question. Some of the people we interviewed for the project have already passed away, which just underlines the importance of this documentation for future researchers.”

Local Modernism

“While constructionist and Stalinist architecture are well known in Western historiography, the soviet period of the second half of the 20th century is practically unknown, and limited to the level of clichés about unbearably somber public spaces,” Ritter explains about the context of the project. “The situation indirectly demonstrated that the existing research was lacking. Even though post-war modernism is a topical discussion point in an international scope, the Eastern Bloc countries are rarely mentioned.” In both speaking to the curator, and in the exhibition's substantial book, it is pointed out several times that “soviet” is not always equated with “Russian”. One should, rather, call it “local modernism”.

In characterizing the architectonic identity of the regions, Ritter mentions that the soviet architecture in the Baltic states has an obvious leaning towards the Scandinavian. “Simple and functional form, precise details and a relatively high quality of execution are rarely associated with our notions of soviet-era buildings. Russification of the architectural profession was not so pronounced in the Baltic countries, especially not in Estonia. In addition, the Baltics, both before and after WWII, identified quite strongly with the concept of modernism, whereas Stalinist architecture was classified as belonging to Russian culture, and therefore, foreign.”

Photo: Frédéric Chaubin. Druzhba Sanatorium, Yalta (Ukraine), built in 1985

Ten years ago, the French photographer Frédéric Chaubin (1959) began to travel to the former soviet republics in order to document the most extravagant examples of modernism. The goal was to show how variable the soviet state's architecture had been in its last decades. Chaubin accounts for this architectonic variety with the slow demise of the Soviet Union itself, which gave the architects increasing freedom to work as they wished. The photographer was taken with the idea that his series of photographs not only supplemented a history that “had not yet even been written”, but that it also turned on its head the 20 year-old cliché that had taken root in contemporary photography – that post-soviet countries are portrayed as being only gray and degenerate. In opposition to this, Chaubin chose to show Utopian, almost comically futuristic structures. This post-soviet amnesia, concerning a regime that had only just recently seen its demise, creates a peculiar atmosphere. The objects photographed seem to float in limbo. They were built in the recent past, but they are no longer looked upon as a part of today. “That made me aware of the fact that history does not write itself. We must think it up, we must risk making mistakes. We have to imagine it,” writes Chaubin. The 2009 series of photographs was collected and published by the Taschen publishing house. In February 2012, the series was exhibited in the Vilnius art gallery Vartai, where it was shown alongside photographs portraying life in soviet times, taken by Antanas Sutkus and Romualdas Rakauskas. Lithuania has a special role in Chaubin's photographic series, since that is where he was when the idea first came to him in 2003.

The highest peaks of Lazdynai captured in the photo project I Spent 7 Years in My Uncles Home as a Servant by Robertas Narkus and Milda Zabarauskaitė, 2011

The stories about how these cracks appeared in each country – through which architects were then able to execute more unusual projects – are many. One of these is the bedroom-community of Lazdynai, on the outskirts of Vilnius, which is visible from the center of the city due to its location on a forested hill. In an attempt to fight against the invasion of Khrushchev-style apartment buildings in the city's historical center, in the early 1970s a group of Lithuanian architects won the right to create a sort of satellite-city on the edge of Vilnius. The project was inspired by the Finnish practice of building residential neighborhoods in hilly woodland areas. Although the soviet authorities looked upon the project with suspicion, it got the go-ahead, and in 1974, the project team was awarded the Medal of Lenin for Architecture. The neighborhood, which is still inhabited, is viewed as not only an example of the bureaucratic struggles that took place between architects and the soviet authorities, but also as an expression of national identity.

Another example is a phenomenon that happened in Estonian architecture in the 1970s and 80s, and that has no counterpart in Latvia. With their discussions, exhibitions and provocative projects in paper architecture, the so-called “Tallinn Ten”, aka the “Tallinn School”, made a name for themselves. The group's architects followed the international art scene of the time, drew inspiration from Finnish modernism and Russian constructivism, and showed interest in film and design; these activities led them to being known as “the young and the angry”. What they did was challenge the practice of architecture – by redefining it.

Ugliness and Amnesia

In characterizing the modernist architecture of the 1950s, 60s and 70s – and not only in the soviet context, but on a world-wide scale – the adjective “brutal” is often used. The word “brutal” came into the lexicon in 1953, when the British architects Alison and Peter Smithson derived the word from the French béton brut, or “raw concrete”, which was a phrase used by Le Corbusier in describing the poured concrete with which he had constructed several buildings in the post-war years. Interestingly enough, one of the most adamant critics of brutalistic architecture was Prince Charles, who called structures made in this style – “piles of concrete”. And then in December 2012, in the “In Memoriam” section of Manhattan's City Journal, Theodore Dalrymple managed to reporach the just-deceased Oscar Niemeyer for his “inhumane architecture”, which is “enjoyable only up until the moment when one must actually live in it”. A British writer and former prison psychiatrist, Dalrymple has always been a passionate critic of brutalism in architecture, calling it “cold”, “monstrous” and “impersonal”. But is it? This question is also posed by the organizers of the Lia-Asta Knāķe exhibition – the Latvian Museum of Architecture.

Neighborhoods made up of soviet-built block-apartment buildings are one of the first to be referred to when talking about “ugly”, “impersonal” and “cold” architecture. ARHIDEA architect Toms Kokins has an opinion on that, as he told Arterritory.com: “In terms of the buildings themselves, everything is alright. The problem lies in what is going on between them. When we're inside our flats, we don't think of what the building looks like, or what we look like – we have curtains, we walk around in our underwear, and we're warm. The problem arises when we approach the buildings; the problem is in the buildings' immediate surroundings – this is a zone that we don't perceive as a living space, but rather as a transit zone – full of discomfort and potentially dangerous. In the best scenario, there's a free parking lot – in which side mirrors get stolen anyway. Correspondingly, negative emotions are projected onto the building's appearance, and along with this comes the associated “soviet” life experience.”

Photograph by Ieva Epnere. From the cycle Mirorajons (Pļavnieki), 2007

Kokins sees the answer in precise identification of the cause of this negativity: “Hardijs Lediņš, who had a degree in architecture, made a cinematic examination in 1988, titled “Cilvēks dzīvojamā vidē (Man in His Living Environment)”, in which he pointed out one of the fundamental problems in the construction of these neighborhoods – the forecourts of these buildings are like a stage, with a potential audience of 100. This is a situation that most people tend to avoid in their daily lives. The negative emotions in these forecourts have to be eradicated and replaced with a pleasant and unforced experience. Bright, geometrical designs on the facades don't help; you have to start with the foundation that is underfoot. You have to create a reason for people to spend time in the forecourt, to meet with one another and feel free. What are the opportunities for children to play hide-and-seek in the courtyards surrounding these block-apartments? To barbeque sausages or play chess? Opportunities must be provided. An important part here must be played by architects, urban planners, environmental designers, and the leaders of facilities' management and their ability to speak to the co-ops and inhabitants of the buildings,” says Kokins.

“This is not just a problem in the former soviet republics. In the West, several masterpieces of modernism are also being destroyed, or are under the threat of destruction,” is how Katharina Ritter, curator of the Vienna exhibition, comments on the prevailing impression of the ugliness of the buildings. “However, if we're speaking about the Soviet Union, then the architecture is deeply linked with the experience of the regime. Among the locals, the architecture is often perceived as something that “has happened to us”, and which has little to with “our own culture”. The legacy is seen as “foreign”, or even “Russian”.”

Forecourts in Riga. 1970s. Photo from the Latvia State Archive of Audiovisual Documents

It has been remarked that not only in architecture, but in the culture as a whole, there occurred a kind of post-soviet amnesia, when after the fall of the USSR in the 1990s, people erased the evidence of the old regime as something undesirable, as even never having been in existance. “That was the first post-soviet decade, and at the same time, the first decade of the “new world order”, when everybody was in a rush to throw into the political market their new, hastily-put-together identities and new historical roots, in which the soviet wasn't included because it seemed to be something inorganic – a sort of mistake, something forced, and like a misstep in the way things normally would have gone,” says Viktor Misiano during his interview with Arterritory.com. “Something similar, by the way, had been experienced by the colonized countries which, upon having received independence, began to erase the memories of their colonial past. This phenomenon of post-colonial theory has, thanks to Leela Gandhi, been termed “the will-to-forget”. But the problem – or more correctly, just one of the problems! – hidden here is that by removing the soviet past from our countries, our belonging to the modernity of today becomes questionable. Because the soviet past was our modernity at that time. We had no other, of course!”

In 2007, Tallinn's KUMU museum hosted the Viktor Misiano-curated Russian art exhibition, “The Return of Memory”, which sketched out the second decade of the post-soviet period. It was a time when “the memories started to come back”. The beginning of the new millennium was a time during which we slowly began to acknowledge the recent past, and we sought to reconnect with it.

In returning to architecture and Riga, the transition from the modernist era to the post-modern one seems to be most visible in Riga's Old Town. Built in the modernist tradition, the monumental ensemble of the Latvian Red Riflemen was reconstructed in the 90s, thereby linking it to the medieval Old Town and the rebuilding of the Town Hall Square and the House of the Blackheads. To make room for this, the Riga Technical University's laboratory building, which had been built in the modernist style, was torn down; a wing of the Riflemen Museum also came down. A grouping of structures and narratives from various eras can attract tourists, but for the city's local inhabitants, it creates a “schizophrenic perception of the urban environment”, formulates architect Oskars Redbergs. Many people become confused among the architectural reconstructions, monuments and commemorative plaques from various time periods, and even from commercial objects of the modern day – that can all be found in this urban environment. This holds true not only for Riga, but for a whole slew of cities that, immediately upon gaining independence, feverishly tried to forget their newly-built “decorations”. Tallinn has been described as being much the same. Triin Ojari, editor-in-chief of the magazine MAJA, writes on the website www.a4d.lv: “Because of the shameless privatization of public spaces and the lack of coordinated politics in planning that occurred in the early 90s, the main thing of note to see in Tallinn is a chaotic and contradictory image in which various historical strati live precariously alongside each other”.

Two Lenins in Grūtos Parkas, Lithuania

It's worth making a small, yet spicy, side note on all of those memorials to Lenin, Stalin, Karl Marx and such – which were the first to “fall” along with the collapse of the regime. Another testament to the fact that prejudices and “memory losses” are beginning to fade in the new millennium is a strangely amusing park in Lithuania. In 2001, Lithuanian businessman Viliumas Malinauskas invested his money in a peculiar enterprise. His Grūtos Parkas, which Time magazine ranked last year as one of the ten strangest amusement parks in the world, lies 130 km southwest of Vilnius and is home to practically all of the soviet-era monuments, sculptures and busts – 86 in total – that were torn down in Lithuania after the reinstatement of independence. The park has already been nick-named “Stalin World”. In its opening year, the park received the Ig Nobel Prize – an American parody of the famous Nobel Prize, which is instead awarded to achievements that could be described thusly: “At first they make you laugh, but then – they make you think.” Grūtos Parkas also features soviet-style cafes and even a small zoo. It goes without mentioning that the park has always found itself in a crossfire of contention, and Malinauskas hasn't even brought all of his ideas to life. One plan that ended up being shelved was to transport visitors to the outlying park in train cars – of the sort once used to deport people to the Gulag... I'll just add that Moscow also has a Park of Fallen Monuments, and that Budapest has an open-air park called Memento, but these two certainly don't have the air of an amusement park.

Rebuild It, or Tear It Down?

Reconstruct it, rebuild it or tear it down? Now that the post-soviet “hangover” from the 90s is long gone, and our eyes have been well rinsed-out during the first decade of the millennium, then in 2013, the issue we face is truly acute – to not act on hastily-made decisions. The excuse for ghosts of the past will soon loose its alibi. “The lifespan of any building, if it doesn't have any special social or historical value, will be dictated by economics – whether or not the investment necessary for upkeep and reconstruction will bring a return,” Toms Kokins tells Arterritory.com. “If reconstruction won't be profitable, then sooner or later, the structure will either collapse, or it will be torn down; this is a natural part of urban development.”

One of the most unprofitable buildings turned out to be the Riga Athletics Stadium (Sporta pils) – one of the largest modernist public buildings to be built in the post-war years, and which was torn down at the end of 2007. Built in 1970, its main function was as an indoor hockey arena with seating for 4500. For a long time it was the most important hockey center in Latvia, and in 1992 it was awarded the status of a National Sports Center. Although soon after, this once “pride of the city” became better known as a market bazaar for hawkers of clothing and even – plumbing supplies.

One of the many examples of a soviet-era building getting a second wind is the CAC Contemporary Art Centre building, in the heart of Vilnius' Old Town. Built in 1968 as an art expo center, it belonged to the Lithuanian Museum of Art up until 1988. Since 1992, CAC has taken the modernist building into its own hands, and has created a 2400 sq. meter space for holding exhibitions, even accommodating the interior to fit the “white cube” aesthetic. Currently, it is still the largest space in the Baltic countries dedicated exclusively to contemporary art.

Lithuanian National Gallery of Art (NGA) in Summer 2007. Photo: Katrīna Ģelze

Another object of note right there in Vilnius, on the right bank of the Neris River, is the Lithuanian National Art Gallery; it is housed in a building that was designed in the 1960s, but only built in 1980, and which was originally the Lithuanian SSR's Museum of the Revolution. After Lithuania gained independence in 1991, the museum was closed. Still in good repair, the building was given to the Lithuanian Museum of Art, to use for establishing a future National Art Gallery. The building was reconstructed according to plans designed by the architects Audrius Bučas, Darius Čaplinskas and Gintaras Kuginis, thereby acquiring a contemporary feel; it was opened to the public in 2009.

Approximately ten years ago, the previously-mentioned Latvenergo building in Riga also went through a reconstruction. “The architect Ingurds Lazdiņš won the contract to reconstruct the Latvenergo building. With flowers in hand, he came to me in the institute and requested the blueprints indicating how the panels were attached to the facade walls,” architect Lia-Asta Knāķe tells Arterritory.com. “Only then was I made aware that a reconstruction project was being planned, in which all of the existing facade was to be removed and replaced with glass. I petitioned for this plan to be revoked, and the Monument Preservation Committee was also on my side; the Latvian Association of Architects decided that the building must be preserved in its original form, so that it can serve as a historical example of how buildings used to be designed.

The architect redid his design, sticking to guidelines that said that he may do whatever he wishes with the inside, but that the outside of the building “may not be touched”. The outer walls had, of course, become quite worn since soviet times, and the fortified concrete even had bullet holes. During reconstruction, the windows were replaced and the facade was refurbished, using today's techniques, materials and professional builders. The building came back to life and everyone began to like it, because it no longer looked run-down.” It should be mentioned that, along with the building's reconstruction, it became known to the public at-large that the huge structure had been designed by a woman. In addition, the catalog for the Vienna exhibition contains an article from Latvia; the authors of the article, Maija Rudovska and Iliana Veinberga, chose to write about women architects exclusively, covering such well-known figures as Marta Staņa, Zane Kalinka and Ausma Skujiņa, among others.

A completely different fate was had by the one-time Hotel Latvija (now known as Radisson Blu Hotel Latvija). Although the building was completed in 1976, it was opened for use only in 1970. The 26-story structure was ensconced by a two-story addition that contained an entry vestibule, cafe, restaurant, shop and an exhibition room named “Latvija”. A group of artists, headed by Ojārs Ābols, was responsible for the hotel's interior design; a kinetic sculpture by artist Artūrs Riņķis, “Sakta (Brooch)”, decorated the hotel's facade. The hotel was designated as the highest “B Category” hotel of the USSR's State Foreign Tourism Committee, with the purpose of serving organized foreign and soviet tourist groups. At the end of 1998, it was decided to remodel the building in two phases, the last of which (2004-2006) made truly stark changes. Behind the scenes, opinions vary on how successful, well-founded and harmonious the resulting object has turned out to be.

Tallinn TV Tower after reconstruction in 2012

Tallinn's Viru Hotel is also legendary, even though it currently looks quite bedraggled, and is linked to a shopping center. Built in 1972, the hotel is still in operation, and one of the rooms has even been made into a museum about the KGB. In soviet times, guests of the hotel had no idea that the 22-story building had a 23rd floor, accessible only by stairs, which had a radio center that eavesdropped on the conversations going on between guests – both in the hotel rooms and at the restaurant's tables.

“Every building has its own fate, and in my opinion, all possibilities are valid. There's just this little thing called good taste in architecture, and being able to see what is valuable in a building. As with any old building,” architect Zaiga Gaile says in speaking to Arterritory.com. “The buildings erected in the soviet period differ in quality – in both architectural and structural terms. There are those that are of such bad quality, and made of dangerous materials (asbestos), that they should be blown up and not rebuilt. A current issue on the table is the Television Center on Zaķu Island [in the Daugava River], which is architecturally good, and a symbol of the city – but it is has become structurally unsound, and reconstruction would be very expensive. On my desk right now are the blueprints for the former Computing Center on Pils Street 8/10, in the center of Riga's Old Town. The facade of the first floor has been walled up, and the tiles between the windows are a “shitty” shade of brown. The building is frightful, and I expect that I won't have any moral obstacles in redoing it.”

Due to safety issues, the observation deck on Tallinn's Television Tower was closed to visitors in 2007. But the tower was reopened already last year, after being rebuilt by the Estonian architectural office KOKO Arhitektid. Specially built for the 1980 Moscow Olympic Games' sailing competition (which was held in Tallinn), the TV Tower has now welcomed the 21st century – with Teletubby Land-like, white “bubble” furniture, informative touch-screen kiosks that look like futuristic mushrooms, and on the 22nd floor – a Scandinavian-style cafe with a panoramic view.

The first wide-screen movie theater dedicated to kids Pionieris in Riga

“I'm sad about what was lost in the reaping that occurred in the first years after independence – the restaurants Sēnīte and Klidziņa, the movie theaters Pionieris, Blāzma, Liesma and Daile, and the colorful Stalin- and Khrushchev-era shops, cafes, and bars, of which almost none have survived. It's paradoxical that the new generation is collecting anacient soviet inventory from old factories, and building reconstructions of the era from scratch,” admits Zaiga Gaile.

Other soviet cities also experienced the loss of movie theaters. In soviet times, the cinema was a fundamental part of the state's cultural life, and impressive theaters were erected in the city centers of many of the republics, including in Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia. After the reclaiming of independence, the soviet infrastructure was chaotic and falling apart, and these buildings became a hot commodity on the real estate market. In a short period of time, private businesses managed to acquire and liquidate almost all of the movie theaters in Vilnius, transforming them into residences, department stores, casinos and shopping malls. Almost ten years have passed since the movie theater Lietuva, built in 1965 as an example of soviet modernism, was closed down; it had been the largest movie theater in Lithuania, and home to the Vilnius Film Festival. In Riga, most of the soviet-built movie theaters were turned into nightclubs. Ironically, post-soviet themes are now being examined on movie screens, such as Aiks Karapetjans' feature film, “People Out There” (2012).

A still from the feature film “People Out There”, 2012

“One can't help but notice that in the last few years, popular culture has shown interest in life in the block-apartment neighborhoods: graphic designers and painters take inspiration from the buildings, and photographic projects, films, music videos and stories are being made and written about the buildings and the people who live in them; the buildings' designers are now glorified,” comments Toms Kokins on the situation going on today. “It is the modern era yearning for something real, for something static and permanent. For instance, a block-apartment house is true to the bone – every concrete panel does its job, and nothing else. It is like a gray canvas on which everyone has the opportunity to express themselves through how they decorate their balcony. It's a residential building, and nothing more.”