Cutting through the 1970s

Gordon Matta-Clark and Anarchitecture

20/06/19

This year on 22 June, Gordon Matta-Clark (born Gordon Roberto Echaurren Matta) would have turned 76. Only four years after the legendary and controversial exhibition Anarchitecture – created by the artists’ group of the same name and held in March 1974 in an artist-run gallery at 112 Greene Street in New York – Matta-Clark, aged 35, died of pancreatic cancer. However, his legacy and superworks of art and architecture have left an indelible effect on the culture of the world and, indeed, keep on living. His radical artistic practice was built upon the themes of urban development and social changes within society – anarchy as a slogan spread around the United States in the 1960s: firstly, as a protest against the Vietnam War, and secondly, as a reason for people to discover the predatory depths of their own subconscious.

Gordon Matta-Clark

Gordon Matta-Clark, son of Chilean Surrealist painter Roberto Matta and American artist Anne Clark, had just finished his studies at Cornell University’s School of Architecture in 1968 – one of the most radical years of the last century. At that time, an offshoot of Students for a Democratic Society, known as the Weather Underground Organization, became influential in major cities of the eastern U.S. by demolishing the surroundings and installing bomb factories in some townhouses. As the bombs exploded and general confusion took effect, deconstruction as a concept became dominant. The same happened with the overall concept of anarchy, which had ideologically inspired many of the aggressive protesters as well as young artists. Anarchy and deconstruction as starting points in art brought together many similar-thinking people; moreover, they resounded ideas that had been previously pivotal in the art world. How could it not be so? – many of the artistic expressions and styles prominent throughout the first part of the 20th century had been inspired by social and political acts, and were imbued with a desire to resist and deny the previously existing order. With anarchy in mind, deconstruction became a normal plan of action – an artistic function for achieving one’s goals. In the U.S., the biggest difference by the end of the 1960s was that this dismantling had obtained very specific and often extremist outlines. Moreover, deconstructing no longer meant simply denying or resisting. From a philosophical point of view, deconstruction has always been an interesting and interpretative concept, based on a belief that a broader meaning (of the idea of deconstruction) can be understood best through a close-up of details. In other words, before the ability to deconstruct comes the need to build something.

Gordon Matta Clark, Conical Intersect. 1975.

After graduation, Matta-Clark, who had gained a good education during his studies at Cornell (he had also taken a year’s leave to study French Literature at the Université Paris-Sorbonne[i]) and was interested in rethinking the formerly adopted principles of architecture, found himself in a psychologically (but also physically) deeply controversial situation. The anarchic environment and bomb blasts in New York were threatening to become a shock to the young graduate, and easily could have contaminated his experience. In other words, thinking about introducing new architectural ideas in a failing city seemed quite unnecessary. However, Gordon Matta-Clark decided to ignore the pressure as he took inspiration from what was happening and started a completely new concept that combined art, design and architectural space. One of the most important encounters in Matta-Clark’s life happened in 1969, when he met conceptual and performance artist Dennis Oppenheim at Cornell’s art gallery just before his return to New York. Oppenheim introduced him to his art dealer, which led to Matta-Clark producing a completely new series of photos for a group exhibition. Photo-Fry (1969), or fried Polaroids in oil, was something like a ritual to him. First of all, the transformation of the image allowed for the monitoring of the versatility and changes in the material. Secondly, these cooked pictures and postcards were a witty novelty in the contemporary art scene, and to some extent, paved the way for the young artist’s passion for food. A few years later, on 25 September 1971, a group of comrades launched the restaurant Food, which would quickly become a meeting place for eating, drinking and discussing art.

Gordon Matta-Clark, Anarchitecture. 1974.

But let us return for a moment to a phrase seen a couple of paragraphs previously: before the ability to deconstruct comes the need to build something. It is indeed true that physical deconstruction requires real working material, a source that has been created beforehand. For Matta-Clark, the whole city became this material to operate with as he began creating new dimensions of old and forgotten places, spaces and forms. Since the 1930s, one of the most influential and renowned masters and thinkers of architecture in the United States had been Le Corbusier – his architectural school and urban planning methods were being adopted by many emerging American architects, and his treatise Vers une architecture (first published in French in 1932) was required reading for every student of architecture, including Matta-Clark. However, the younger generation quickly switched sides, and critical rethinking of grand-masters like Le Corbusier became increasingly popular during the 1960s and 70s. Postmodernism and the changing dimensions of time dictated new rules, prompting a review of the ideas about ‘one total architecture’ as expressed in Vers une architecture, incorrectly translated into English as Towards a New Architecture. In 1970, Robin Evans published an essay on socio-political aspects within architecture and its relation to human freedom; needless to say, the title of the article was a heretical play on Le Corbusier’s work – Evans’ essay was titled Towards Anarchitecture. Whether Matta-Clark was aware of Evans’ essay is still under debate because the name of The Anarchitect Group (of which Matta-Clark was also a member) allegedly came about as a result of informal conversation. In any case, the old saying that ‘ideas are in the air’ holds especially true for the 1970s and the creation of anarchitecture. Around the beginning of this new decade, Matta-Clark performed his first ‘cutting’; it took place in the sauna of his new loft. As he was experimenting with filming his friends, Matta-Clark simply cut and extracted a fragment of the room, thereby revealing the structure of the wall. He would go on to do the same thing at Food, allegorically comparing the structure of a wall with a sandwich and its various layers. That same year, Gordon Matta-Clark travelled to Chile, where he had an exhibition at the Museo de Bellas Artes in Santiago. There the young artist made a wall cutting in which the flow of light played great importance. The cutting was made from a men’s bathroom in a basement, up through the building to its roof; by placing mirrors at different angles within the resulting hole, sunlight could reach to the very bottom. The higher light besieged the depths of the underground. Gordon Matta-Clark had created something similar to an eternal space of time, turning an architectural unit into a paraphrase about the never-ending quality of life.

Gordon Matta-Clark, Photo-Fry. 1969.

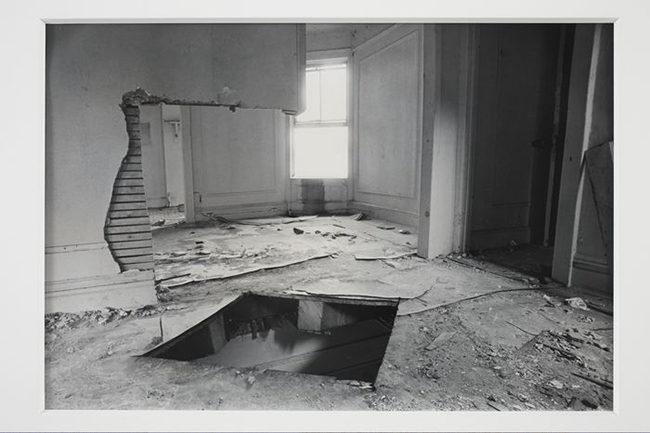

The Anarchitecture group, whose members were Tina Girouard, Bernard Kirschenbaum, Carol Goodden, Jene Highstein, Richard Landry, Richard Nonas, Laurie Anderson and Gordon Matta-Clark himself, emerged in 1973 and focused on combining visual manifestations with different language games. Already before that, Matta-Clark had begun his series Bronx Floors – he wandered through the peripheral neighbourhoods of New York, made cuttings, and documented it with photos.

Anarchitecture group, Anarchitecture drawing. 1974.

The Anarchitects mostly criticised modernist ideas of contemporary culture and the way architecture was being perceived. Not architecture as art, but architecture that is art was one of the aspects that interested these artists. The title of the group, as is self-evident, is a combination of two (at that time very significant) words – anarchy and architecture. And, although several important and independently acclaimed artists became members of the group, one of their main objectives was to simply be a collective. At the previously mentioned exhibition in 1974, all works were submitted anonymously, thereby highlighting architecture as the central object of the show. Conversations about it and ideas and their realisation were of interest to these young artists, and that was what they also presented through different media. In 1974, Matta-Clark wrote: ‘Architecture is environment, too. When you’re living in a city, the whole fabric is architectural in some sense. We were thinking more about metaphoric voids, gaps, leftover spaces, places that were not developed.’

Anarchitecture group, Anarchitecture drawing. 1974.

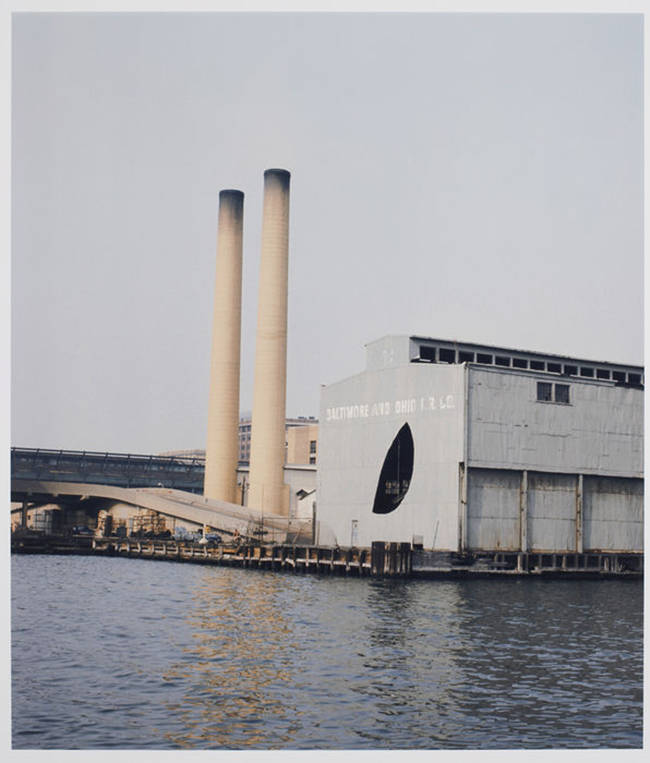

One of the most famous and critically acclaimed projects by Gordon Matta-Clark is Splitting (1974), in which he completely cut in two a one-storey house in Englewood, New Jersey. The house was set up for demolition and this allowed Matta-Clark to freely play with the material. By cutting the house apart, he allowed a ray of light to pass through the ‘inside’ of it, thus expanding the meaning of ‘architectural digest’. On a larger scale, he continued the cutting project by performing Day’s End (1975) in a hangar on the piers of New York and Conical Intercept (1975) – a work that was a part of the Paris Biennale. In this project, he used abandoned 17th-century buildings and created massive drill holes right through their structures.

Gordon Matta Clark, Splitting. 1974.

In 1976, Gordon’s twin brother Sebastian committed suicide from the window of his brother’s loft, which left Gordon very affected. As an homage to Sebastian, Gordon created Jacob’s Ladder at documenta 6 in Kassel – a several-meters-high tower with mounting ladders made from white netting. From a distance, the nearly transparent stairs resembled a fragile and elusive structure similar to a cobweb. In 1978, Gordon Matta-Clark married Jane Crawford, and on 27 August, just two months after his birthday, he died.

Gordon Matta-Clark, Day’s End. 1975.

With Anarchitecture in his heart, Gordon Matta-Clark obtained the almost impossible – by cutting a hole in a house, he became an icon, leaving deep imprints in both contemporary architecture and art.

A Jacob’s Ladder. Remembering Gordon Matta-Clark. Trailer.

To celebrate the life and oeuvre of the artist recent years have been honoured with several exhibitions by Gordon Matta Clark. In 2016 a solo show with his works was on view at the Marian Goodman gallery in Paris and in 2018 the artist’s legacy was show at the David Zwirner gallery in London.

Starting from 2017 a travelling exhibition “Gordon Matta-Clark: Anarchitect” is being shown in various exhibition halls around the world. The first show at the Bronx Museum of the Arts in New York was followed by an exhibition in Jeu de Paume in Paris and a show “Gordon Matta-Clark: Anarchitect. Anu Vahtra: Completion through removal” in KUMU Art Museum of Estonia. From 20 September 2019 till 5 January 2020, the same show will be on view at Rose Art Museum in Brandeis University in Waltham.

Until then, an exhibition dedicated to works of Gordon Matta-Clark, “Out of the box”, from 6 June till 8 September can be viewed at the Canadian Architecture Centre in Montreal.

[i] That happened in 1963, a year after he had enrolled in the School of Architecture at Cornell University. After a bad car accident Gordon fractured his jaw and went for a year to live in France.