In the Presence of Vija Celmins

23/05/2012

Although I am standing in the living room of one of the most sought-after female artists of the 21st century, it doesn’t seem that intimidating now. Vija Celmins’ (1938) Soho apartment feels very relaxing and calm. “I have a new studio out in the country, in the wilderness where I can see no houses – just fields, woods and trees. It makes me very happy,” says Vija Celmins just before asking me, if I were an artist as well.

“No, unfortunately I am not.” I reply.

Vija Celmins. Courtesy of McKee Gallery

“Oh, good! It’s not unfortunate. Art is a field that’s very full right now and very competitive. I have kids that come help me, and they have had a very difficult time getting anyone to even look at their work,” she explains while leading me to her bright white studio, which is effortlessly merged with the living space.

As I step into the serene room, the artist stops and leans over one of her latest galaxy prints to make a few adjustments. Usually after she has done the print Vija Celmins asks her assistants to complete some of the elements, such as making the stars clear and white. But she doesn’t think it’s similar to the practice of other artists, who have turned their artistic career into a commercial enterprise.

“Some of the artists today are just like manufactures – they hire other people to do all their work. But I can’t do that because then it’s not really my work,” she says. “What each artist lays in his or her artwork in the sensibility, which is basically a combination of all kinds of little decisions that only that person can make. Otherwise it’s just a copy that anyone can do.”

Slate Tablet. 2006–2010. Private collection

Courtesy of McKee Gallery

She also adds that in her opinion “there is no longer such a thing as an avant-garde. There are just people that are more commercial or less commercial; a few become successful but most people don’t make any money in art.”

Reworked from photographs, Vija Celmins’ paintings, drawings and prints are built upon a relationship between the surface of the image and the deep space. But it was only after rejecting her primary interest in reconstructing such objects as airplanes, guns and electrical appliances, that the artist turned her attention to the intricate representations of nature – oceans, deserts, and galaxies. One of such “re-described” ocean paintings is also present in the studio, which I find myself mesmerised by.

Strata. 1983. Nr.15/37. Private collection

Courtesy of Mūkusalas mākslas salons

“That painting just came back from an exhibition,” noticing my attention explains the artist. “It is rather melancholic.”

“But that’s exactly where it’s magnificence rests,” I confess.

“That must be a Latvian thing.” She laughs. “Actually, before you came here I was thinking of what would make my art Latvian but I couldn’t find the answer. My work is rather severe and kind of mental. I don’t know if that’s really Latvian. I think it comes from my interest in working with an image and trying to do something different with it. I don’t really know what would make me a Latvian artist besides maybe a touch of melancholy.”

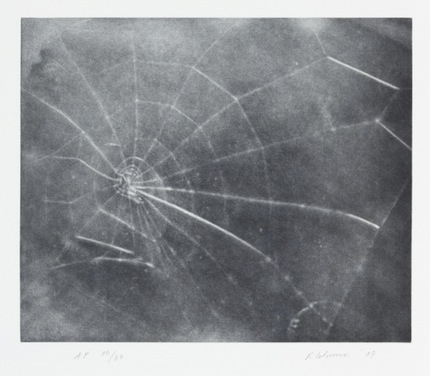

WEB Nr. 5. 2009. Nr.20/30. Private collection

Courtesy of Mūkusalas mākslas salons

We have moved away from the bright light of the studio and are now sitting in the artist’s office, which holds a large variety of exhibition catalogues from Vija Celmins previous shows. Although the artist has never tried to hide her Latvian heritage, which she is actually very proud of, there have been moments when she wished that people wouldn’t put too much focus on it.

“Sometimes I don’t really like to write it because then people think that’s the most interesting thing about you. You have to be born somewhere and I was born in Riga. My parents had nothing to do with painting. No one in my family was ever a painter. They were all doctors, builders or involved in science.”

Vija Celmins was born in Latvia in 1939 but at the age of ten she immigrated to the United States with her family, settling in Indiana. Due to the language barrier, as she did not speak or write English, Celmins spent much of her time at school and at home drawing and painting. But it was only in 1961, after meeting a strong community of students and artists at the summer session at Yale University, New Haven, when she decided to become a painter. Vija Celmins received her BFA from the Herron Institute in 1962 and her MFA from University of California, Los Angeles, in 1965.

Concentric Bearings c. 1984. Nr.24/34. Private collection

Courtesy of Mūkusalas mākslas salons

“I was lucky to have shows right after graduating the university. I remember that at that time I sold a few things for $200. Now it seems like nothing but then, in the early 60’s, you could live on $2000 a year.” She pauses. “I also got a job immediately after graduating the University of California, which I believe is quite impossible to do now. It was just for one year. I had to teach painting, drawing and anatomy. Although, I am not a person who paints people, at least I was able to make a living right away. Subsequently I got offered a part time job, which was then followed by a show and some pretty good reviews in the paper.” She admits that those early jobs at the university kept her “alive” so that she could live and do her real work.

Although Vija Celmins lived in Los Angeles from 1962 to 1980, it was only towards the end of that time frame when she began to make a presence. “I wouldn’t go away. Young artists often tend to start something and then they disappear. Especially women used to do that – they would get married. I also got married but I couldn’t leave my art. Art was always my number one priority. It was my big relationship. My generation was really the first generation of women who stood up for themselves. It was quite difficult. At that time almost all of the galleries were dominated by men; I was often the only woman there. Many times people didn’t pay any attention to me, even though I was doing a lot of things much better than they were. I was often very isolated but I didn’t mind. I liked being alone,” she recalls.

.jpeg)

Untitled (Ocean). 1969. Philadelphia Museum of Art, Pennsylvania. Courtesy of McKee Gallery

In 1981 the artist decided to try her luck in New York. “I had forgotten how much I actually liked bugs and birds. Los Angeles is completely bug-free. I loved the desert, which probably influenced my work quite a lot, but California has this rather artificial landscape - the city is so giant that it has been overtaken by a car culture.”

“It did take a while for people to begin to go and look at my work here in New York,” admits Celmins. But the acceptance of the New York art scene did gradually come as well. “I was very persistent. Little by little I began to have a reputation and people started to say “Oh, yes. I know what you did.” It has taken me a long time to get here - I am talking from 1963-64 to now.”

“I think all those things would be a little more difficult to do now because there are so many artists and so many different directions,” admits Vija Celmins. “If I was now 22 years old, I don’t know whether I would be aggressive enough to do it. It seems that today you have to be quite assertive because there is so much competition.”

When I ask about the supposed 10-year waiting list that the eager art collectors have formed in order to acquire one of her paintings, Vija Celmins replies, “I can’t even comment on that because I don’t really pay any attention to it. If I paid attention to it, I would probably be a little upset. I don’t think that’s true – it’s overstated. That’s just talk. I think there is a waiting list because I concentrate on the image so much that it takes me a long time to do it. I don’t have enough work. A lot of people make 10 things a day or certainly 10 a week, or 10 a month but I haven’t been that prolific.”

Night Sky #6. 1993. Collection of the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, MN. Courtesy of McKee Gallery

Just recently one of Vija Celmins drawings “Untitled #8“ was included in Christie’s “Post-War and Contemporary Art Evening Sale” alongside Mark Rothko’s record-breaking “Orange, Red, Yellow”, which then became the most expensive artwork ever sold at an auction ($86,882,500). Vija Celmins drawing, however, also did exceptionally well – it sold for $1,142,500, breaking the artist’s highest auction sale price to date.

“For me it’s amazing that other people like my work because the work really lives with other people. It lives with you first but then it’s the other people that make it really alive.”