How art can heal the scars left by a catastrophe

Japan after the March 11, 2011 catastrophe

Arta Tabaka

04/04/2013

In April of 2011, one month after the earthquake, tsunami and resulting catastrophe at the Fukushima nuclear power station, the famous Japanese actor and star of TV and radio, Taro Yamamato, suddenly announced the end of his career. Voicing loud accusations at the Japanese government for its actions during the situation at hand, Yamamoto announced that he can no longer keep quiet and ignore this problem. Instead of taking part in the public's much-loved television dramas, Yamamato declared that henceforth, his life's mission is to save the futures of both children and all of Japan, and that in his opinion, this can only be done by getting rid of all nuclear power plants. That same month, Yamamato began working for a company that creates solar-power systems, and he also started to actively campaign for a country free of nuclear power stations.

At the current moment, Yamamato has left his job with the solar-power systems company and is active in politics, singling out Japan's liberation from nuclear power as his main goal. Of course, Yamamato is not the only politician with the same main objective. Nevertheless, in a country that constantly uses electricity, and whose largest cities are blazingly lit up 24 hours a day, this sounds like either a blatant lie, or, the exact opposite – a deep, but naïve, romantic belief.

Regardless, Yamamato's story is a perfect example of how the events of March 11 impacted the lives of a multitude of people. It made them notice things that weren't noticed before, and it made them turn to things that used to seem unimportant, or even useless, because suddenly, in their calm and orderly lives, a huge chasm appeared, and out of this chasm emerged the question – how do we go on?

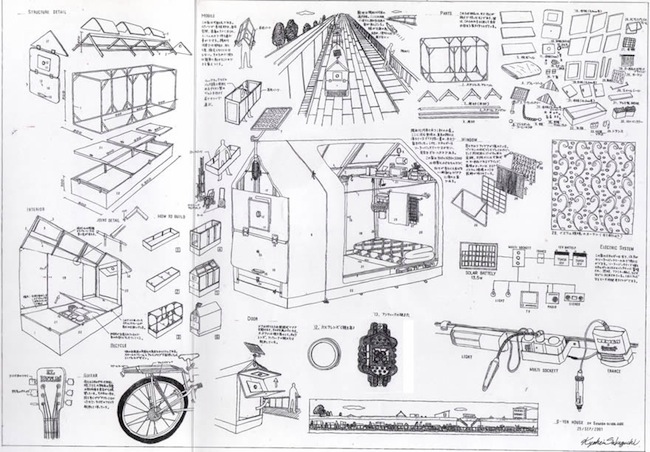

“Zero Yen House”

Since March and up to the current day, Kyohei Sakaguchi is quite possibly the most frequently and loudly mentioned name in the spheres of art, culture and society. After the events in March, and in fear of his family's safety, Sakaguchi demonstratively moved from Tokyo to Kumamoto (a city on the island of Kyushu – the most southern of the four main islands that make up Japan). There he acquired a traditional-style Japanese house (for a symbolic amount of money), and fashioned it into the Zero Center – a refugee camp for those who have lost their house due to the natural disaster and who wish to move as far south as possible because of worries about nuclear radiation, or – for anyone who has left their home, for whatever reason, and is looking for a new place to live. As the center's name indicates, there is no rent or fees to pay; it is precisely this avoidance of the need for money that has been, right from the start, one of the essential cornerstones of Sakaguchi's work. In addition, in an effort to escape from the political and informational chaos that governed Japan at the time, Sakaguchi proclaimed that the center is a separate nation, independent from Japan, and appointed himself as its leader (Sakaguchi has also published a book – “Creating an Independent Nation”). All of these undertakings served to make Sakaguchi enormously popular; consequently, his previous works were rediscovered, and suddenly, they spoke to masses of people who had found in them a new meaning that they had previously not seen.

A solar mobile home. From Kyohei Sakaguchi's exhibition, “Practice for a Revolution”, which just closed in February of this year at the Watarium museum of modern art.

Sakaguchi is an architect by profession, and began to take an interest in the way of life of the homeless while still a university student. The motivation for this interest was a chance meeting with a homeless man – a Mr. Suzuki, by the Sumida River. Suzuki had outfitted his self-made dwelling with solar batteries, had transformed the nearest library into his personal bookshelf, and the adjacent park – into his living room. Moved by Suzuki's way of life, Sakaguchi began spending a lot of time with other homeless people, interviewing them and observing their daily routines. This research into the lives of the homeless became a photographic book, “Zero Yen House”, which is an artistic study on the dwellings of homeless people, mostly in and around Tokyo. The dwellings were constructed on a budge of “zero yen” – or rather, with no budget – but they contain everything necessary for full-blooded living. Along with the creation of his own dwelling, with his own hands and on a minimal budget, Sagaguchi declared that real estate egencies really aren't necessary – that they are just a government invention, and that in truth, the land belongs to all of us.

“Even though there is no garden, there is a garden,” written in Japanese language.

Alongside his work with the dwellings of the homeless, Sakaguchi put together a project called “4D Gardens” – photographs of gardens in Tokyo, a city which, despite its immense size, seems quite green when one walks through it. In a city where people cannot afford to make large and fancy gardens, gardens are made in the strangest of places; to some, they may even be so nontraditional as to not even be called gardens. Much like the “Zero Yen House”, “4D Gardens” also raises the questions – what is this house that belongs to us, the garden that belongs to us, and the space that we create around ourselves? – and how very conditional these questions are in relation to our own point of view about how “public” things can also be “private”, and that this is the way that it just should be.

“4D Gardens”

Sakaguchi and his ideas had their followers right from the start, but it was only after the events of March 11 – when so many people lost their homes or were forced to leave them, when faith in the government disappeared and the time had come to contemplate the very fundamentals of one's life – that his ideas finally reached a huge audience, giving Sakaguchi an almost cult-like status. His suggestions gave answers to people who were looking for a new way to live and new things to hold on to, when everything around them had collapsed and faith in a stable Japan had disappeared.

Sagakuchi's ideas on how to build a house without a budget are at the heart of the 2011 film, “Mobile House”.

Released in 2011, the film, “Mobile House”, was based on Sagakuchi's ideas on how to build a house without a budget, and how to live without any money. The film reflects Sakaguchi's personal experience living with homeless people, and also gives practical advice on how to build such a house; it popularized a way of life that is independent of government or any other rule, and illustrated the ability to live wherever, without any money.

The film, “My House”, is a story about a homeless man and ways in which to survive.

This film was followed by “My House”, which is a film about a homeless man and ways in which to survive; it is based on themes from Sakaguchi's book. Now the words “mobile house”, just like the Zero Center, are foreign to no one. Sakaguchi has also started a career as a musician, and his concerts are a new way in which to express ideas and reach as many people as possible; it is now, more than ever, that the Japanese yearn for his ideas.

Taro Okamato's paining, “Shibuya Station”

In 2008, the artist group Chim ↑ Pom – at the core of which are six young artists working in various fields and with a focus on social issues and the urban environment – used an airplane to write, in the sky over Hiroshima, the word “PIKA”, which is Japanese for “atomic bomb”. This performance evoked both strong resonance and critique – the group of artists was accused of intolerance, ignoring social norms, and overstepping taboos. In the words of the artists themselves, the point of the skywriting was the wish to remind everyone that an atomic bomb was once dropped, and that we still live in a world supported by atomic energy – and that a small mistake could lead to history repeating itself. (A book about the performance, the idea itself and the resulting reactions, titled “Why can't we make the sky over Hiroshima 'PIKA'?”, came out in 2009).

In May of 2011, in Shibuya Station and next to the painting, “Myth of Tomorrow”, by the Japanese avante-garde master, Taro Okamoto, the same artist's group put up an image of the partially-collapsed Fukashima nuclear power station – done in the same style as Okamoto's painting. The choice of Okamoto's painting was not unfounded, and not just because of its central location and huge size. (Shibuya is one of the busiest stations in Tokyo, and the painting measures 30 m x 5.5 m.) Created at the end of the 1960s, Okamoto's painting symbolizes the atomic bomb that was dropped on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, and is an expression of the artist's opinion on the resulting consequences.

A partial image of the Fukushima nuclear power plant that Chim ↑ Pom placed on the lower right-hand side of Okomato's painting.

Once again, this incited allegations of vandalism and disrespect – which ended up being louder than the attempts at understanding what it was that this group of artists wanted to express with their actions. In support of Chim ↑ Pom, the head of the Okamato Museum announced that this incident was not vandalism because the painting itself was not damaged, it did not suffer any harm, and that the method in which Chim ↑ Pom attached their work indicated their respect towards “Myth of Tomorrow”. Hirano did add, however, that “the painting by Chim ↑ Pom directly mirrors Japan's situation and lack of safety, but in an artistic sense, it is nothing new and does not deserve any accolades”. Even though the Chim ↑ Pom group's actions weren't highly praised artistically, it did indicate a new feature of modern art in Japan – artists are no longer just quiet observers, but active participants who express their ideas directly; they are even rebels.

Similar characteristics can also be seen in society itself – beginning with April 2011, mass demonstrations and rallies have taken place throughout the country, of the like that were last seen during the student rebellions in the 1960s.

No. 2 “Fire”. From the series, “Hiroshima Panels”. 1950

Radiation and the impact of nuclear energy has not been a foreign subject in Japanese art for a long time now. In 1950, Iri and Toshio Maruki began their famous series of works titled “Hiroshima Panels”, which consists of 15 large-format paintings depicting the destruction caused by the atomic bomb. Four years later, in 1954, the film director Ishiro Honda made the movie “Godzilla”, which is about a monster that has been created by the deleterious effects of radiation – a mutant gorilla-and-whale hybrid that emerges from the ocean. Numerous sequels and remakes were made (even comics and a book came out), and now Godzilla is a character known throughout the world. Nevertheless, Japanese art has never been as active, participative, bold and self-assured as it is right now.

“A Worker Pointing”

On August 28, 2011, the Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO), which owns the Fukushima nuclear power station, observed in one of their surveillance cameras a worker facing and angrily pointing a finger at the camera, and this went on for 20 minutes. According to TEPCO, it was not possible to identify this person and he is still unknown. However, everyone knows that this person was artist Kota Tekeuchi, which can be verified by looking at the artist's own blog. The blog tells of his search in finding a way to help the inhabitant's of Japan's Tohoku region after the catastrophe; this led to him taking a job with TEPCO, which was intensively looking for workers at the time to deal with the emergency situation. Influenced by the experiences of long-term workers at the plant, and aware of the dangers to his health from finding himself in a collapsing nuclear power plant, Takeuchi quit this job rather quickly – but he has left behind an anger-filled, harsh and straightforward video.

In interviews, Takeuchi asserts that he can exhibit this video as his own because no one knows who made it and who owns it, which means that anyone can request the rights to it. Takeuchi also stresses that everyone must decide for himself whether the person in the video is or isn't him, and that everyone must take responsibility for their own words anyway. He adds that the person in the video has taken care to remove all possible signs of identification on his clothes, resulting in a lack of clear evidence of whether or not it really is him. In this way, the unknown person symbolizes the situation in the country as a whole, namely – some information is not released, some is hidden, some is pure lies, and some is simply made up. As a result, no one knows what the truth really is, and it is increasingly difficult to find a way out of the situation.

The shoes, “Healing Fukushima”, by Sputniko!

In a completely contrary manner to these rebellious attacks on TEPCO and the Japanese government, some artists are looking for ways to help and create hope that a future still is possible. While thinking about the effects of radiation, the artist Sputniko! created a pair of shoes that she titled “Healing Fukushima (Nanohana Heels)” – the heels of the shoes contain canola seeds which are seeded into the ground as every step is taken. The idea for the piece was based on research by Belorussian scientists showing that canola seeds can absorb cesium and strontium from the soil. As a result of this study, in the year 2000 the governments of Belorussia and Ukraine initiated the seeding of 50,000 hectares of land in the territories affected by Chernobyl – in the hope of rehabilitating the land for agriculture. Sputniko's! shoes are part of the “Canola Blossom Project”, which has been actively working since the catastrophe and regularly holds meetings and creative workshops in Fukushima Prefecture; the project's aim is to make the area liveable again and to come up with possible solutions.

“Things I Can Do Myself”, by Yuken Teruya

In a similar way, the New York-based artist, Yuken Teruya, created the piece “Things I Can Do Myself”. Using newspapers with articles on the Fukushima catastrophe, Teruya cut out plants and blossoms from them, thereby creating the impression that they are growing out of the pages of the newspapers – out of the tragedy itself. It was Teruya's way of reminding us that whatever may happen, nature continues to go on, that spring will return with its new buds and new life, and that it is nature that will, once again, bring everything to order.

Raising of the lighthouse.

In Tsubasa Kato's project “The Lighthouses – 11.3 Project”, in the city of Iwaki a lighthouse was constructed from materials collected from the destroyed territories. At first, the lighthouse was on its side, and then hundreds of locals helped in raising it upright – symbolizing the rebirth of the Tohoku region. The project was documented in photographs and on film, and it spread throughout the whole country; in some places, symbolic raisings of the lighthouse are still going on today.

The artist Ichiro Endo has gained wide popularity with his project, “Rainbow Japan”. It should be mentioned that since 2006, Endo has been living in a van upon which is written “Go for Future”; he drives around Japan collecting people's wishes for the future, and then writes them onto his van. In 2012, the artist came up with “Rainbow Japan”, which is much the same idea, but this time his aim is to use Japan as his canvas, and his van as a paintbrush – as he compiles messages with which to inspire the inhabitants of the Tohoku region.

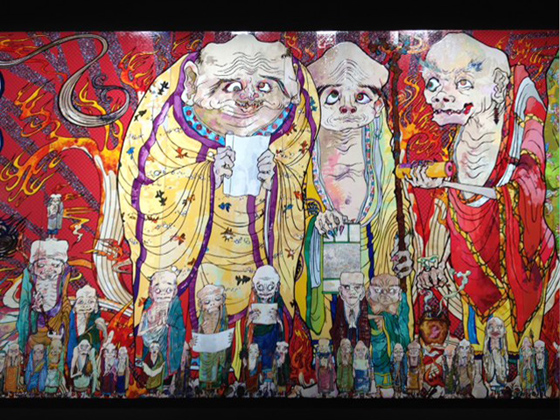

While the young artists combine their creative expression with activism and altruistic goals, the most world-renown (and also highest-earning) Japanese artist is Takashi Murakami. In his solo show that took place in February 2012, in Doha, Qatar, he presented a work dedicated to the events of March 11: a 100 meter-long painting titled “500 Arhats”, which is composed of 100 paintings, each one at a size of 1m x 3m. The piece has been done in Murakami's characteristically colorful and flat manner, and depicts 500 arhats. Murakami explains his shift towards Buddhist themes with the fact that, since time immemorial, people have looked to religion for salvation from inevitable situations, and that religion can both heal and bring rebirth. He adds that the artistic portrayal of 500 arhats is an ancient Japanese tradition, and that portraying them in paintings and sculptures is a memorial in itself, as well as a way to lessen one's pain through the act of creating.

A section of “500 Arhats”, by Takashi Murakami

Murakami has attained fame and popularity through his colorful characters – made in the style of manga and animation – and is currently most renown for his collaboration in designing bags for Louis Vuitton, and other marketing-orientated projects. Although “500 Arhats” can be seen as Murakami's reaction to what is going on in Japan, its reserved and fixed manner in the midst of Japan's art media has categorized him to an era that has already passed – a time when order, economic stability and a carefree joy in frivolous things were what ruled the day.

On my recent visit to the city of Ishinomaki, which was one of the cities hardest hit by the earthquake and tsunami, a man who had lost his shop to the tsunami showed me the model for his new shop. The outer wall of the model was covered in grass, flowers, and even trees. He said that one must live with nature, that both earthquakes and tsunamis are an intrinsic part of nature, and that no one can hate nature for taking away houses or loved ones. Everyone is just angry at the government. And that is precisely what is going on in art, and other movements, at the moment – the glorification of nature and the scorning of government; the return to what we had already forgotten a long time ago.