When I Work, and In My Art, I Hold Hands With God

Getting to know Robert Mapplethorpe

Tabita Rudzāte

14/04/2015

Robert Mapplethorpe

KIASMA, Helsinki

Until September 13, 2015

In the spring and summer of 2014, Paris' Grand Palais showed a retrospective of the works of American photographer Robert Mapplethorpe (1946-1989). This spring the retrospective (in a slightly expanded version) has arrived in Helsinki, serving as one of the first exhibitions since the reopening of the Kiasma contemporary art museum.

On the evening of November 4, 1988, the New York penthouse apartment located at No. 35, West 23rd Street, was full of people. Among the almost 200 hundred guests who had come to celebrate the 42nd birthday of photographer Robert Mapplethorpe were such luminaries as the film-stars Susan Sarandon and Sigourney Weaver; Greece's Prince Michael and his consort; the Earl of Warwick; Tom Armstrong from the Whitney Museum; the gallerist Mary Boone; and Mapplethorpe's photo stylist Dimitri Levas. Also present were a flock of famous faces from the worlds of glossy magazines, galleries, auction houses and museums, not to mention the usual art collectors, friends, and a group of men in tight black leather clothing. Waiters in black jackets scurried about with trays of champagne, and cocktail tables were laden with large cans of beluga caviar. In the middle of the room stood a separate table, heaving under an ever-growing mountain of presents. Every few moments yet another bouquet of flowers arrived from well-wishers who couldn't be present. The birthday boy himself looked to be surprisingly healthy, contentedly sitting in a chair with his iconic skull-topped walking stick in hand. Singly or in pairs, guests would come up to Robert, crouch down, and whisper their regards and adulations. Although everybody knew that this was Mapplethorpe's last going-away party, nothing on the surface of things gave this away, and the party was as boisterous as ever. As the Prince of Greece said afterwards: “Robert has style. That can't be learned. You either have it or you don't”.

Four months and five days later, on March 9, 1989, Robert Mapplethorpe died in a Boston hospital from complications arising from AIDS.

Self-portrait. 1988. © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

“I come from suburban America. It was a very safe environment and it was a good place to come from in that it was a good place to leave.” Robert Mapplethorpe was born in 1946 in Floral Park, a suburb of Queens, New York. Born into a Catholic family, he was the third of six children. At the young age of 16 Mapplethorpe enrolled in Brooklyn's Pratt Institute, where he studied sculpture and majored in the graphic arts. His first creative works were mixed-media collages, objects and jewelry – even these early pieces bore his trademark use of eroticism.

Mapplethorpe met the musician and poet Patti Smith in 1967, and they immediately formed a creative and emotional bond. At first they lived in separate apartments next door to each other, and Robert eventually kicked a hole through their shared wall so as to make communication simpler. Three years later, they moved in together.

The friendship between Mapplethorpe and Smith has become one of New York's urban legends, and as these legends tend to do, they often become exaggerated and romanticized. They were two beautiful, wild-looking youths without money or connections, but they were extremely dedicated to reaching the goal of becoming famous in their individual realms. For Smith, this was music; for Mapplethorpe, it was art. In her 2010 biography Just Kids, Smith openly describes what their life was like in the New York of the 60s and 70s – cheap hotels, scrounging for money to pay for food and rent, love affairs, the club scene, their creative collaboration, how they took care of one another, and so on. “At the base of our relationship was a mutual trust. We we never jealous of each other's accomplishments. We inspired one another.” Although in photographs from those days their cool, detached looks and their angular, bony physiques lead one to think of bohemian excess and addictions, in the book they are both portrayed as a pair of rather civilized and loving dreamers.

In 1975, Mapplethorpe created the legendary cover design for Smith's debut album Horses. Hair messily tousled, Smith is dressed in men's clothes – an image that was in direct contrast to what the music industry and the public expected from a woman in rock and roll. The photo was one of Mapplethorpe's first portraits of somebody famous, and it was to be followed by many more.

Patti Smith. 1979. © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

Mapplethorpe's and Smith's creative and domestic partnership slowly came to end at that time – Smith left New York in 1979 and moved to Detroit to be with her future husband, the guitarist Fred Smith. Nevertheless, they stayed very close friends, and since Robert's death, Patti has been an active advocate of keeping his legacy alive – publishing several books on Mapplethorpe, helping organize retrospectives of his work around the world, etc. One of Smith's greatest achievements in this regard was the 2009 Mapplethorpe exhibition at the Accademia Gallery in Florence; Robert's works were displayed next to Michelangelo's sculptures of slaves – the classical figures had always been a special favorite of Mapplethorpe.

“I went into photography because it seemed like the perfect vehicle for commenting on the madness of today's existence.” From Smith's book we learn that Mapplethorpe wasn't at all interested in photography at first because back then, it was quite a complicated process with the developing of negatives and such. He began using pictures that he taken himself with a Polaroid camera – simply because he didn't want to use magazine cut-outs of other people's photographs in his work. Perhaps that is why he is one of those few who are most often referred to as being an artist rather than a photographer – although he eventually developed an extremely complex and powerful technique, conceptually, his work goes beyond the bounds of expression that have been set for the medium of photography. Today there are about 1500 known Polaroids taken by Mapplethorpe. According to the story, Mapplethorpe was gifted a Polaroid camera in 1972 by John McKendry, curator at New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art. McKendry and his wife, Maxine, took Mapplethorpe into their fold and introduced him to the high society of New York, thereby procuring him new friends and clients.

Another notable introduction for Mapplethorpe was made that same year – to the collector, philanthropist and “local aristocrat” Samuel Wagstaff. Having been given Mapplethorpe's telephone number, Wagstaff called the artist and asked him: “Are you the shy pornographer?” Even though Wagstaff was Mapplethorpe's senior by 25 years, they soon became lovers. The relationship was mutually beneficial – Wagstaff provided Mapplethorpe with material support, confidence, and assurance of his talent and ability; whereas Mapplethorpe encouraged Wagstaff to collect art photography. “He became obsessed with photography,” Mapplethorpe has said about Sam. “He bought with a vengeance. It went beyond anything I imagined. Through him, I started looking at photographs in a much more serious way. I got to know dealers. I went with him when he was buying things. It was a great education, although I had my own vision right from the beginning.” It is widely believed that it was due to Wagstaff's zeal that photography finally gained prestige as an artistic medium and came to be accepted as a valid, and expensive, form of museum-quality art. In 1984, Wagstaff sold his art-photography collection to the Getty Museum in California for five million dollars.

Back then, Wagstaff and Mapplethorpe were known as what could be called the couple terrible of New York – they participated in various underground sex and drug orgies, obsessively pursued erotic gratification, and at the same time, searched for aesthetic completeness. When their romantic relationship ended, Wagstaff continued to financially support, and love, Mapplethorpe. They were good friends, and both were HIV positive. When Wagstaff died in 1987, it was revealed that he had bequeathed all of his worldly goods (estimated at a worth of seven million dollars) to Mapplethorpe.

Leather Crotch. 1980. © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

Mapplethorpe's first photography show, “Polaroids”, took place in 1973, in New York's Light Gallery. In the mid-seventies, he changed his professional “instrument” to a Hasselblad medium-format camera, and began to take pictures of his friends and acquaintances from all walks of life.

“Most of the people in S&M were proud of what they were doing. It was giving pleasure to one another. It was not about hurting. It was sort of an art. Certainly there were people who were into brutality, but that wasn’t my take. For me, it was about two people having a simultaneous orgasm. It was pleasure, even though it looked painful. Doing things to people who don’t want it done to them is not sexy to me. The people in my pictures were doing it because they wanted to. No one was forced into it. For me S&M means sex and magic, not sadomasochism.” It was at this time that Mapplethorpe began doing that which later made him scandalously famous: photographically documenting New York's gay S&M community in all of its most extreme forms. In 1978 he published X Portfolio – thirteen altogether shocking, but technically and formally, perfectly executed photographs with homo-erotic and sadomasochistic motifs; it received critical acclaim.

“It’s [S&M photography] past history to me, but I think they’ve influenced the way people look at my pictures, even though they might not have even seen the S&M pictures. I mean, I’ve had reviews and such, especially in the gay press, where they’ve been really nasty about them. They attacked me as a person, and decided I was a certain kind of person because only a certain kind of person would take those kind of pictures. It was so weird. It really depressed me.” It should be noted that for many years, these pictures remained exclusively in book form because none of the New York galleries were willing to show them. They were first exhibited publicly only in the spring of 1987, in the exhibition “Censored”, held at the alternative art space at 80 Langstron Street in San Francisco. Shortly thereafter, Mapplethorpe told ARTnews: "I don't like that particular word 'shocking.' I'm looking for the unexpected. I'm looking for things I've never seen before … I was in a position to take those pictures. I felt an obligation to do them." In 1989, some of these pictures were included in Mapplethorpe's posthumous traveling exhibition, “The Perfect Moment”. One of the hosting institutions was to be the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., one of the oldest private art galleries in the US. Even before the exhibition's opening, there was wide public discussion on censorship and the subsidization of art with taxpayers' money. For instance, the American Family Association made use of the moment to criticize the government of supporting what they called “nothing more than the sensational presentation of potentially obscene material." The Corcoran Gallery ended up refusing to show “The Perfect Moment”, but the underwriters moved on and eventually exhibited at the non-profit Washington Project for the Arts, and to large crowds at that.

Read in Archive: An express interview with Museum Director of Kiasma - Pirkko Siitari

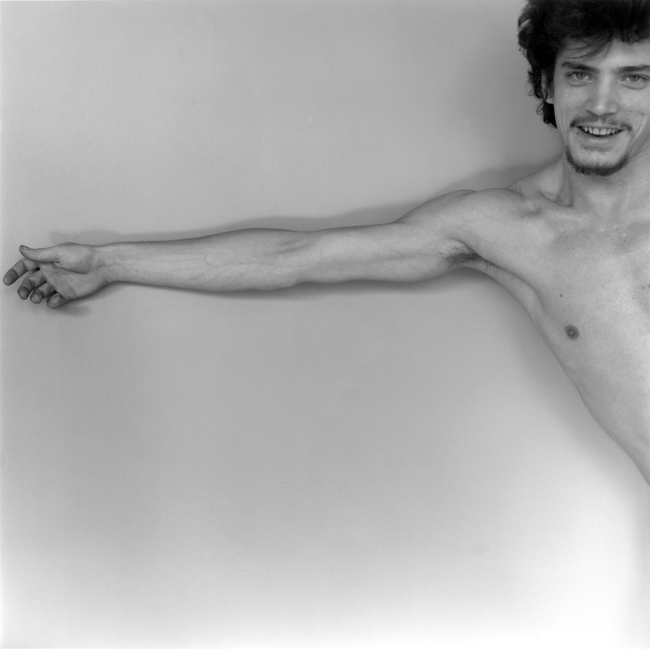

“I am obsessed with beauty. I want everything to be perfect, and of course it isn’t. And that’s a tough place to be because you’re never satisfied.” Mapplethorpe generally worked in the studio, creating stylized large-format compositions that complied to, and at the same time challenged, the standards of classical aesthetics. He developed and fine-tuned various complex technical methods and formats such as photo engravings and platinum prints on paper and textiles, among others. It could be said that in the early 80s, Mapplethorpe had developed his style to the degree that his pictures seemed to be sheathed in a timeless elegance. He worked in a variety of genres: still lifes, interior shots, portraits and self-portraits. By acquiring a unique and intensive style of illumination and using silvery, archaic light, everything that Mapplethorpe photographed – be it a face, a flower or somebody's ass – “materialized” almost as if it were classical sculpture.

“I played around with the flowers and lighting, so that was a good way to educate myself.” Sophisticated photographs of flowers take a special place in Mapplethorpe's oeuvre; much like all of his other works, they appear to be erotically charged and clearly allude to interpretations of a sexual nature. Mapplethorpe began taking pictures of lilies, tulips, orchids and chrysanthemums at the end of the 70s, putting to use all of his technical and stylistic abilities to endow the blooms with the noblesse of fragile alabaster. One could say that he transformed something as “trivial” as pictures of flowers into a contemporary and popular genre.

Poppy. 1988. © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

“The formality and intensity of the early photographers are evident in what I do. I use a rather slow film and long exposures...and it gives you a certain intensity. I’m working with old fashioned techniques...there hasn’t been a creative portrait photographer since Nadar in the 19th century.”

Another aspect of Mapplethorpe's body of work are his portraits of famous people. Arnold Schwarzenegger, Robert Wilson, Richard Gere, even the Archbishop of Canterbury posed for him. “People ask me, who would you really like to photograph? I don’t have anyone, you know? I’m doing a book on women, my next book’s called On Women, I have to come up with a list. I have to make an effort, to get some of these name women because the publisher wants some in there . . . I could care less. I see the point; but then you have to write a letter, get on the phone, talk to their agent—it’s so awfully complicated. Because of that, I’ve never photographed Mick Jagger, I’ve never photographed—you can go through the list—David Bowie, most of the key people, because it’s too complicated. I always hope that maybe they’ll come to me, but I don’t want them badly enough to go through those changes.

Arnold Schwarzenegger. 1976. © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

Continuing with this theme, Mapplethorpe's self-portraits must not be left unmentioned – some are unabashedly narcissistic, some are theatrical, while others are harshly truthful. He took pictures of himself as a hooligan brandishing a knife, as a horned Satan, as a terrorist with a machine gun, and as a diva wearing a fur stole. As Mapplethorpe's life neared its end, he tended to include skull motifs in his self portraits – usually as a topper for his walking stick.

Self Portrait. 1980. © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

Undeniably, the main subject in Mapplethorpe's art is the body – the human body: male and female nudes in which he was able to capture the perfection of classic sculpture in combination with an erotic charge.

In 1980 Mapplethorpe met Lisa Lyon, a world champion female bodybuilder. She modeled for him for several years, which resulted in a series of portraits and figure studies, as well as a book, Lady, Lisa Lyon (1983).

Lisa Lyon. 1982. © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

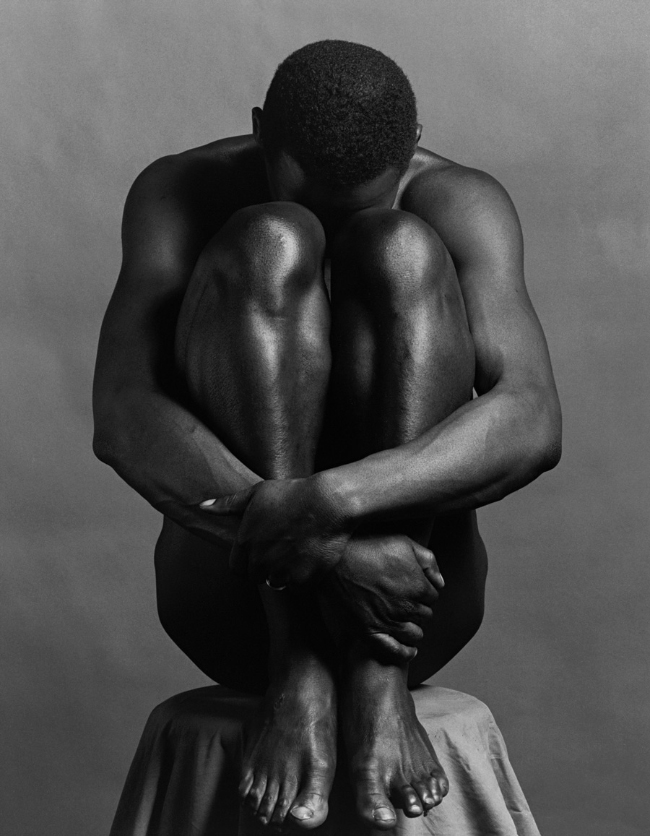

However, one could speculate that it was pointedly with his male nudes that Mapplethorpe reached his artistic summit. He had already distanced himself from the S&M theme before he fell ill with AIDS, and had also quit with the “shock” scenes. He moved on to using the muscular male body in his art as only the ideal form of an energetic object. “At some point I started photographing black men. It was an area that hadn't been explored intensively. If you went through the history of nude male photography, there were very few black subjects. I found that I could take pictures of black men that were so subtle, and the form was so photographical.” Mapplethorpe's powerful and sculpturally clean compositions of male bodies were a fusing of classical sensitivity with homo-erotic content, at a time when male nudes were not a popular theme in photography. In 1986, Mapplethorpe officially showed his photographs of black male nudes in the exhibition “Black Males”, which was then followed by a print edition, The Black Book. At the time, the exhibit was harshly criticized and the pictures were deemed to be “exploitative”.

From the series Black Males. 1981. © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

“Photography is a whole different—it’s so many different things. I think it’s more interesting than being a painter because you’ve got all these options. You can do books, you can do postcards, you can do calendars, you can work for magazines, you can reprint, you can do album covers; then you make art objects as well […] I think you have a really interesting life as a photographer.”

Robert Mapplethorpe lived and worked in the Chelsea studio that Wagstaff had bought for him. The interior design of the apartment was extremely stylish, and in 1988 it was even featured in the famous American magazine House & Garden (Mapplethorpe had, on occasion, worked with the magazine in a professional capacity as well). “You create your own world; the one that I want to live in is very precise, very controlled,” Mapplethorpe once said about his precisely ordered living quarters. As time passed, his closest friends had noticed how he had moved away from the “underground scene”, and had started inching closer to the company of the upper classes. In recalling having gone with Mapplethorpe on a visit to an apartment in the Upper East Side, an associate of Mapplethorpe's remarked: “I think he wanted to become a society photographer. Once, leaving someone’s town house on the Upper East Side, he said, 'I wouldn’t mind living like that'.” In 1986, Robert Mapplethorpe was diagnosed as suffering from AIDS.

Self Portrait. 1975. © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

In the middle of 1988, Mapplethorpe's expansive exhibition at New York's Whitney Museum brought him recognition from a much wider slice of the general public than ever before. He has said that his only regret was that the short amount of time he had left in this world would not allow him to fully enjoy his fame. On the evening of the exhibition's opening, Mapplethorpe was temporarily released from the hospital where he had been staying on an almost permanent basis by then. “I’ve seen people at openings, straight people I’m talking about, running around so nervous. You should be able to have a good time at your own opening. It’s your work and you’ve done it all your life, and if you don’t feel comfortable with it, something’s wrong.”

Legend has it that Mapplethorpe spent the last day of his life making up two lists: one containing the people who are to be informed of his death, the other – people whom he does not wish to be informed of his death.