Harlem Vogue: Work. Paris. Dupree

Estere Kajema

16/12/2015

“Come on, vogue

Let your body move to the music”

Madonna, Vogue, 1990

Even though Vogue, as a dance, only became highly famous and popular after Madonna’s video for her song Vogue, in which the legendary singer dances and “strikes poses”, Vogue actually emerged in the 1970’s, in New York's Harlem.

Vogue is a dance movement with a deep, controversial and often surprising history. It is a movement that came from the urban slums, yet stood for all of the possible majesties and graces of the great neighborhood of Harlem. In the 1980’s, Vogue was confronted with AIDS, but the tragic disease was only one struggle amongst many layers of obstacles that the LGBT community had to go through. Hatred, racism, homophobia, disgust – and that barely covers everything Vogue had to confront.

In 1957, the famous artist John Cage wrote the essay “2 Pages, 122 Words on Music and Dance”. The peculiar and unorganized order of words, spacings and thoughts reminds me a lot of Voguing. Cage puts these words in a column –

love

mirth

the heroic

wonder

tranquility

fear

anger

sorrow

disgust.

These words perfectly summarize the ideas and rhythms of Vogue - because Vogue is not just about dancing. Vogue is a way of living, it is a rhythm of breath. It is a sentiment and always, always – a contest.

Paris Dupree. Still from Jennie Livingston's film Paris is Burning (71 min, 1990)

HISTORY

Vogue, as a movement, comes from African-American and Latino LGBTQ prisoners. In 1972, Paris Dupree, a prisoner from Harlem, started copying poses from Vogue magazine. He started with simple model poses, then added music and increased the speed of his movement – and that is how the dance emerged.

Voguing strongly depends on Balls – events that the gangs of New York would organize to show their wealth, talents and status. Each performer was supposed to be a member of a so-called House, and each House had a Mother, Father and Children, all of whom would consider each other as brothers and sisters. There was, for instance, the House of Ninja, created and led by the famous dancer Willi Ninja – who called himself Ninja because of his mind-blowing freestyle dancing skills. There was the House of Xtravaganza, the House of Pendavis, and the House of Dupree.

The Houses, the Balls and Vogue were all created and performed by members of the LGBTQ society in Harlem. Drag queens, transsexuals, Hispanic, black, butch and bitchy. The ideas of home and belonging was very dear to members of these Houses – in the 1970’s, there were generally very aggressive and negative views against LGBTQ society; a lot of the members of the Houses were rejected as children and were lonely. For them, a House became home.

However, Vogue should not be only seen as a purely LGBTQ movement – it is a dance of freedom and drama. It is the art of posing, being a model, being seen, being on stage. It is a dance of pride. Balls and Houses with drag queens existed long before Vogue – but the dance was a way to express oneself without dressing up to pose.

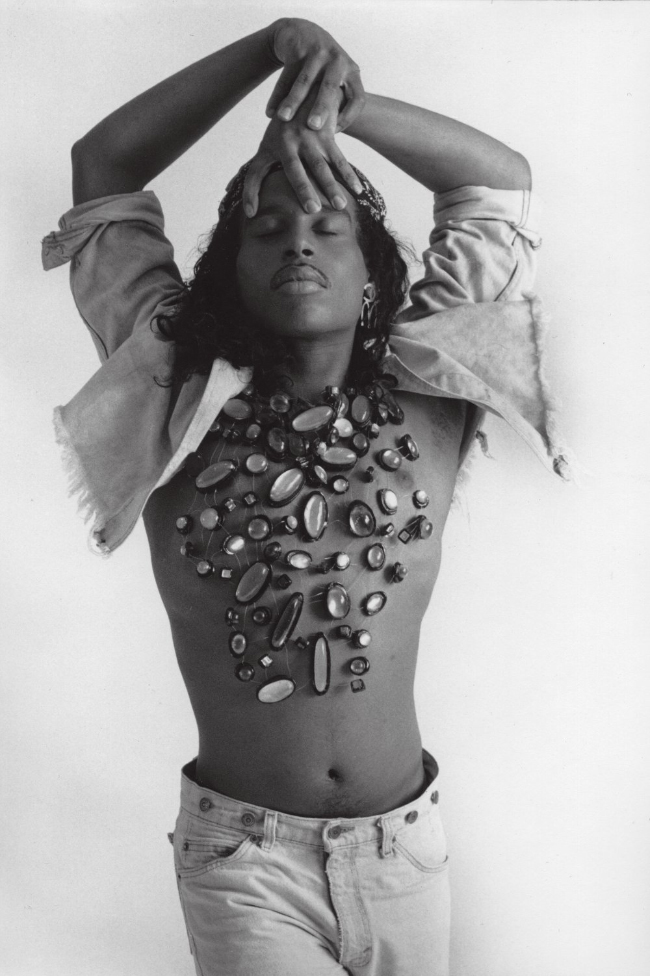

Willi Ninja. © Photo: Chantal Regnault. From Stuart Baker's book Voguing: Voguing and the House Ballroom Scene of New York City 1989-92

RULES AND RITUALS

There are eight possible positions of hands (although new way Vogue offers ten of them). Up, down, left, right – and you can alter these movements as much as you want. Don’t rush – take your time. Pose as if there were a camera in front of you. Put your best clothes on – your highest heels, feathers, gold. You must look extravagant. Pick a name that will suit you perfectly. A Ball is a battle, really. You are not allowed to touch your opponent – no pinching or hitting. You can perform a slap, for instance, but you are not allowed to touch. Everything you do must be full of taste and grace – Balls do not tolerate violence and disrespect.

There are four statuses a performer can reach at a Ball – Statement, Star, Legend and Icon. The more you Vogue, the more often you come to Balls, the higher status you gain. If one is a beginner – if he or she has come to a Ball only once or twice, they are Statement – which means that they are trying to make themselves recognizable.

Star is someone who had already been seen on the dance floor. They know the judges, and often behave rather freely on stage. When one starts winning the Balls, they become a Legend, and later – an Icon. There are three criteria by which one is judged on stage:

Style: how well you are dressed, how well does your look help you perform;

Precision: how exact and pure are your movements, how well do you feel the sound;

Grace: how comfortable and natural do you feel dancing and performing.

You will only win, or at least get some points, if you manage to combine all three factors. You have to listen to the music, improvise, and always practice. You have to read your opponent – exaggerate every single flaw your opponent might have, and shade – insult your opponent without actually touching them. You have to be a perfect actor, a model and a queen, no matter the character you are portraying – be it a policeman, a soldier, a girl who’s always standing on the corner – you have to be a queen.

In 1975 Marina Abramović performed Freeing the Body. She wrote a short description for her work:

“I wrap my head in a black scarf.

Performance.

I move to the rhythm of the black African drummer.

I move until I am completely exhausted.

I fall.” [1]

If you try to distract yourself from picturing Maria Abramović performing these words, you can clearly see how they correspond with Vogue. If you exchange the black African drummer with the sounds of house music, you can easily see one of the dancers at a Ball, performing at their best. This almost perfect juxtaposition proves how much Vogue differs from simple dance moves. Vogue is performance in its purest and most artistic form. It is always a ritual, a tradition.

LGBTQ AND VOGUE

There is no doubt that Vogue is closely connected with LGBTQ history and Queer Theory, even though the dance itself is not necessarily excluded to one particular group of people. Vogue witnessed homophobia, trans-phobia, AIDS, drug abuse, rape. In the incredible film Paris is Burning (1990), Jennie Livingston addresses all of these questions in order to show the purity and beauty which are often overshadowed by racial and homophobic hatred.

In his essay “Coming out Crip: Malibu is Burning”, Robert McRuer deals with explorations of “gender trouble” and “compulsory heterosexuality”. He argues that being queer is, in some way, being crip. This is a very western idea, and it is interesting to see that the thought of connecting the queer and the crip has nothing to do with both African and Latino rituals. Ruth Landes, an American cultural anthropologist, writes about the ancient Bahian [Brazil] tradition:

The only men who could take full part in the ceremonies, incorporating divinities through dance and spirit possession, were those who were “passive homosexuals” who, like the women, were “mounted” by the gods. [2]

Don Kulick, another professor of cultural and linguistic anthropology, writes about gender and sexual determination:

The crucial determinant of a homosexual classification is not so much the fact of sex, as it is the role performed during the sexual act. A male who anally penetrates another male is generally not considered to be homosexual... Gender in Latin America should be seen not as consisting of men and women, but, rather of men and non-men, the latter being a category into which both biological females and males who enjoy anal penetration are culturally situated. [3]

Both anthropologists argue that gay men were either sacred or considered to be non-male figures – but in no case thought to be broken, condemned or leprous. It is very important to understand that members of Houses were completely tolerated and accepted for what and who they were in the places where they originally came from. It is also interesting to note that many Ball participants would steal and rob to get their perfect costumes, make-up and accessories. Outside of the Ball, they were gangsters; but during the Ball, they miraculously became queens. If they chose a drag-queen style for their everyday life, they would be hated on the outside, on the streets; but again – during the Ball, they miraculously became queens.

Harlem in the 1970’s was indeed a place full of racial hatred, homophobia and trans-phobia. To explain this, I shall refer to one particular case study – Venus Xtravaganza.

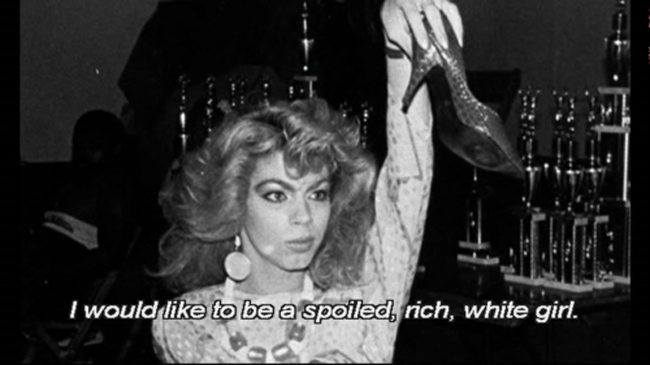

Venus Xtravaganza. Still from Jennie Livingston's film Paris is Burning (71 min, 1990)

Venus Xtravaganza

Venus Xtravaganza was one of the performers at House of Xtravaganza. She joined the House in 1983, where she was kindly greeted by Angie Xtravaganza, the House Mother. Venus had a dream, as she said herself – to be a “spoiled, rich white girl”.[4] As we know, and as can be seen in Paris is Burning, Venus was very poor and had no choice but to work as a sex worker. She was saving money for sex reassignment surgery, to become as much of a woman on the outside as she was on the inside.

In 1988, at the age of 23, Venus was discovered under a bed in a hotel room, four days after she was strangled to death. The murderer was never found, but it was clear that Venus was killed out of an act of trans-phobic violence. Venus was “killed for not being real enough”[5]. It was, indeed, a very tragic death for the House of Xtravaganza – “Angie Xtravaganza mourns the loss of her Child, whom she never felt was cautious enough – particularly in sex work.” Venus’s death opens up space for a different, possibly larger and wider narrative, that goes far beyond Balls and Houses. It shows that Vogue was indeed a highly political movement, or at least it had become one.

Vogue is not a dance. Vogue is shading, dancing like Willi Ninja, having a Family, being part of that Family. Vogue is being flawless, the Venux-Xtravaganza way. Vogue is being fearless, it is about being simultaneously a gangster and a queen. Vogue is a way of living Vogue.

“Ladies with an attitude

Fellows that were in the mood

Don't just stand there, let's get to it

Strike a pose, there's nothing to it.”

[1] Thomas McEvilley, Marina Abramovic: The Artist Body: Performances 1969-1998. Italy: Edizioni Charta Srl, 1998

[2] Ruth Landes, The City of Women. US: University of New Mexico Press, 2006.

[3] Don Kulick, “The Gender of Brazilian Transgendered Prostitutes”, American Anthropologist, 1997.

[4] Paris is Burning, directed by Jennie Livingston (1990)

[5] Barbara Browning, Infectious Rhythm: Metaphors of Contagion and the Spread of African Culture. UK: Taylor&Francis, 1998.