An ambitious archipelago of art

04/12/2012

It is the autumn of 2012, and I am about 20 kilometers from Stockholm, in one of Sweden’s newest art spaces, Artipelag. A large group show named Enlightened is being set up – a memento mori to the incandescent light bulb, which is no longer available in Scandinavia. Among the participants in the show are Spencer Finch, Christian Boltanski, Tracey Emin, Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Jeppe Hein, Monica Bonvicini and Mona Hatoum, to name just a few big international names.

“My favorite piece in the exhibition is Joseph Beuy’s Capri Battery (1985), in which a light bulb has been stuck into a lemon and painted yellow,” reveals Bo Nilsson, the creative director of Artipelag. Nilsson has been actively taking part in the art world since the 1970s, and agreed to an interview with Arterritory.com that would help introduce our readers to the art space that he now manages.

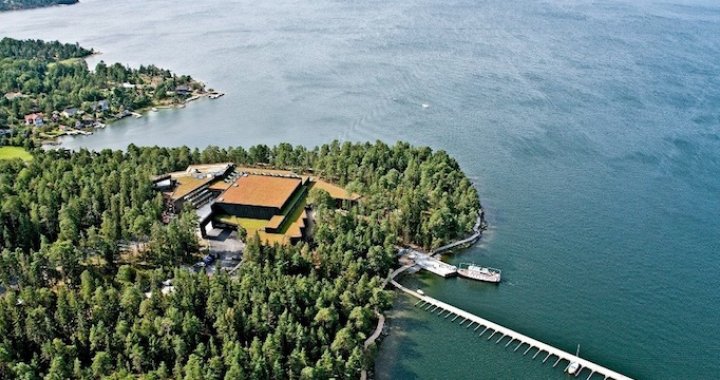

Artipelag opened its doors in June of 2012. Its initiator and sponsor is Swedish entrepreneur Björn Jacobsson, the founder of Baby Björn. During the 1960s, Jacobsson began selling products for children in Stockholm, but his big break came in 1973, when he invented a child carrier that allows adults to carry small children on their chests. The idea of building a beautiful space for art and culture on the archipelago came to Jacobsson in 2000. Twelve years later, the idea has come to life. Right on the sea and surrounded by pine trees, stands a 10 400-square-metre building designed for world-class art exhibitions and cultural events.

Artipelag has two floors above ground level, an underground level and a rooftop terrace, as well as a boardwalk that winds through the surrounding forest and seashore. An 1800-square-meter room, the Art Hall, is intended for exhibitions, while the Black Box – a 1200-square-meter room with a ceiling 11 meters high – is meant for concerts, theatrical productions and conferences. The Black Box has been upholstered in a special black material that reduces reverberation, thereby ensuring a clearer sound and making it feel like a huge television studio. The intention to regularly hold concerts, operas and theatrical productions is a serious one, as indicated by eleven dressing rooms specifically set aside for the artists.

Bo Nillson. Photo: Charlie Bennet

I meet creative director Bo Nilsson at Artipelag’s café, which features a glass wall that gives us an unobstructed view of the misty sea. At the table next to us are six middle-aged patrons having a leisurely lunch and who, judging by their constant chuckling, are having a jolly time. A bit further sits a young family with a baby. On this autumnal workday, the halls of Artipelag are completely empty. Visitor numbers usually swell on weekends. To get to this secluded art space, you can either take a ferry from the center of Stockholm, or take the special Artipelag bus, which makes several trips daily. Nilsson is wearing a black shirt, jeans and brightly colored trainers. His head is topped with a mop of gray hair and his expression is one of measured excitement.

From the 1970s to the mid-1990s, Nilsson worked at Stockholm’s Moderna Museet as head curator, then spent a year working at the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in Denmark. From 1995 to 2000, he was the director of the Rooseum private museum in Malmö, Sweden (the space once occupied by the Rooseum is now the Malmö affiliate of the Moderna Museet). Nilsson has also headed the Liljevalchs art gallery and the Charlottenburg exhibition hall in Copenhagen. With an education in art history, Nilsson says that his best “school” was the time he spent working at the Sydsvenska daily newspaper, where the intense deadlines forced him to formulate opinions on every new art exhibition at breakneck speed. When I ask Nilsson about the state of art critiquing in Sweden, he sighs and says that several newspapers have done away with their cultural sections, and that only one newspaper still retains a meaningful voice – all of which makes for an unproductive situation in terms of developing art critiquing.

In tandem with his work at Artipelag, Nilsson is an associate professor at Stockholm University, and was one of the initiators of its two-year Master’s program for curators. When I ask Nilsson to cite the most important thing that he wants new curators to learn, he answers: the ability to balance between having a good knowledge of how the artists work – in order to intuitively and precisely predict what the artist is capable of, and in which directions he/she could work if invited to create something new for a specific exhibition – and the aptitude to create a group show’s final conception while it is still in the process of being put together, rather than having the “big picture” chiseled in stone right from the start. We continue our conversation, turning exclusively to the subject of Artipelag, which is the first art space that Nilsson has headed since the day it was established.

Tell us about the concept of Artipelag. What is the meaning behind the combination of the words “art” and “archipelago”?

I’m not sure if it would be correct to call it conceptual. Rather, it is a typically Scandinavian way to interact with natural landscapes and live with them in harmony. Entrepreneur Björn Jacobsson, who financed and built Artipelag, has a special relationship with the sea and the archipelago. He has spent many of his summers here and is passionate about sailing. Having traveled through Europe these past 30 years and familiarizing himself with the architecture of art spaces, Björn noticed that the most effective spaces are those that have a rapport with the surrounding environment. One of his sources of inspiration was surely the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in Denmark, as well as the Beyeler Foundation Museum in Basel, and others.

So, Björn Jacobsson was less enamored of the sort of museums like the Guggenheim network, whose buildings are usually in sharp contrast with their surroundings?

In planning Artipelag, Björn invited seven architects to bring him their designs, so that he could choose the one that best suited his vision. He chose Johan Nyrėn who, unfortunately, is no longer with us. He passed away shortly before the project began, which was a huge shock to all of us. But this architect said: “If you want to build another Bilbao – which is like a spaceship that has landed in an incompatible location – then I’m definitely not the architect for you. But, if you want architecture that finds itself a fitting place within nature, then I’m your architect.” This philosophy can be seen everywhere. The café contains an ancient spire of rock that rose above the sea in this exact spot, approximately 1000 years BCE. In the basement level, a cliff side makes up one of the walls. And the wooden exterior of Artipelag comes from the pine trees that used to grow here.

Artipelag from the sea side

Does Artipelag also serve as home to Björn Jacobsson’s private art collection?

No, this is an exhibition hall. There is no trace of a private collection here. Björn is not interested in building a monument to himself, unlike many of today’s collectors. He wishes to create a space where relationships can form among architecture, art and nature, as well as other forms of art. At the opening of Artipelag, Stockholm’s opera theater performed a new production. This is the sort of cooperation we’d like to foster.

To build an art space in a location like this, no matter how beautiful it may be, is a very bold step when one takes into account how far it is from the city’s center. Isn’t the size of your audience an important factor?

Visitor numbers are crucial and it will undeniably take several years to increase them. Our goal in this first year of operation is to have 100 000 visitors. Then we’ll see how we did. Interestingly, our audience is completely different from that at the institutions in the city’s center. Stockholm has about 20 art spaces, which means that each one has its own specific circle of visitors.

How would you describe the people who visit Artipelag?

Interestingly, most of those who visit Artipelag are older people, I’d say the “50 plus” crowd. Why is that? Perhaps the natural environment plays its part, and also many people in this generation have just entered retirement. That is a huge and new trend in Sweden – older people are becoming increasingly active consumers of culture. It wasn’t that pronounced before. Advertising and media specialists assert that no other art institution in Sweden has formed such an obvious target audience at such a quick pace as Artipelag. In addition, I am sure that a large part of those who visit us don’t go to other art institutions. We have harmonious architecture and a good restaurant, and they also like the fact that they’ve been among the first people to go to Artipelag. They don’t feel as comfortable when they go to Fotografiska or the Moderna Museet, because those institutions have a long history of which they know very little about. They don’t feel as if they belong there, because they have just now become actively interested in art.

Do you take these observations into account when working out your exhibition program?

No, we don’t plan exhibitions that would be specifically suited for a certain audience. It is important for us to organize events that, in our opinion, are currently essential, and which no one else in Sweden is organizing.

How many exhibitions do you plan per year?

We plan on holding four large exhibitions a year. We will not be organizing any smaller, parallel exhibitions.

Is Artipelag trying to fill those niches that Stockholm’s institutions haven’t yet gotten to?

In a sense, yes, because there are so many art institutions. Consequently, so many exhibitions are being held that people have become indifferent. That’s why it is important for every show at Artipelag to answer the question: “Why should I go see this?” We’re planning on showing exhibitions with such names as Joseph Beuys, Rudolf Steiner, Cy Twombly, Per Kirkeby, Gary Simon and Jean-Michel Basquiat.

Joseph Beuys. Capri Battery. 1985

Is Björn Jacobsson satisfied with how Artipelag has turned out, and with the exhibitions that are being held here? Does he make regular appearances?

Yes, he comes here every day and never meddles with the planning of the art exhibitions.