Art is Created from Reality. Interview with painter Luc Tuymans

Produced with the support of ABLV Charitable Foundation

Produced with the support of ABLV Charitable Foundation

Elīna Čivle-Üye

11/07/2013

Antwerp-based painter Luc Tuymans (1958) belongs to the circle knows as “the masters of contemporary art”. His works – the characteristic features of which are relationships between pale, almost smeared paints and laconicism – can be found in the collections of the most noteworthy museums and institutions, as well as in famous private collections. Tuymans' art is liked by both curators of prestigious exhibitions and so-called “A-class” gallerists. It is a source of inspiration and a touchstone for numerous young, and not-so-young, artists. And Tuymans is also loved by the public, his works almost constantly available for viewing in both solo shows and group shows being held the world over. And there's more – in the art world, Tuymans himself is also a highly regarded curator (he studied art history at Brussels' Vrije Universiteit in the mid-80s).

Luc Tuymans' creative biography contains practically all of the “medals” of the art world: the Venice Biennale (2001); Documenta (2002); a solo show at Tate Modern (2004); and a retrospective that started its journey in 2011, at the prestigious BOZAR in Brussels, and then continued through several cities in the US. Having attracted numbers usually associated with rock festivals – 90,000 visitors, it completely turned on its head the 21st century's mistaken declaration of painting being a “dead medium”.

At the beginning of August, a retrospective of the works of the famous Italian modernist Giorgio Morandi opened at BOZAR (ongoing through 22 September), with Luc Tuymans as invited guest artist. The dialog between Morandi and Tuymans draws the viewers into an exciting discussion on influences and their role in the creative work of an artist.

Arterritory.com interviewed the artist in his studio, which is located on the first floor of a brick building in a slightly shabby corner of Antwerp. Actually, the buildings on Korte Schipperskapelstraat are either undergoing renovations, or they're being decimated – there are pieces of scaffolding here and there, but then there's a window that looks as if it was smashed just last night. Right around the corner is Antwerp's red-light district – Schipperskwartier, with its piquant “window dressings”.

We both are sitting at the side of a long, white table. The studio's wide windows and walls are also white in shade. It seems as if the only bright accent in the room is the colorfully red packet of Marlboroughs next to Mr. Tuymans. It is continually being emptied – the last ember of one cigarette serving as the light for the next one, the stream of smoke cut-off for not even a moment.

I don't get to see the artist's works in the holiest of holies itself. We meet in the office part of the studio, and as I soon find out, the artist doesn't like to find himself in close quarters with his finished pieces. Tuymans answers the questions fully and deeply. When he listens, it seems as if he's judging all that was left unsaid...

You have never left Belgium. In addition, you've practically spent the whole of your life in your hometown. Famous artists usually head to London, New York...

First of all, I was born here and am somehow linked to this place. Secondly, it's really great to work in a small city! Of course, I could live in New York, Berlin or Paris, but famous artists have the bad luck that someone always needs something from them. And Belgians are a reserved people. Even though they are proud of me, they're not obtrusive; that's why I can feel unbothered here.

I do travel for five months of the year. Belgium is a very small and central country. Brussels, which is just a 20-minute drive from here, is the capital of Europe, and from there I can fly to anywhere in the world. We're close to the Netherlands, Germany, France...

Antwerp itself is a lively and important city for artists and for art itself. That's the way it's always been. Don't forget that already back in the 17th century, Antwerp's harbor was one of the largest in Europe. When Bruges lost its importance, many artists headed here.

How would you comment on today's art scene in Antwerp?

Jan Fabre still lives and works in Antwerp, as does German-born Kati Heck, who's lived and worked here for a long time; and there are many, many more.

The creative sphere in Antwerp has always been, and still is, lively. That includes the music scene – with the rock-group dEUS and Tom Barman at the forefront. It's own kind of “underground” branch of artists is also active here. Like in any small city, everybody knows each other and they work together – they create art, put out their own musical recordings, hold parties. It's a group of young people, around 30 years old, and their works can also be seen in the collection of Antwerp's Museum of Contemporary Art (MuHKA).

I must say, though, that right now the Museum of Contemporary Art isn't functioning the way it should, and many artists are forced to go to Brussels. It's a moment of transition right now. It's connected to the political climate, in large part – the activities of Belgium's Flemish nationalist party, which has now taken the reigns of government in Antwerp as well.

Brussels' Center for Sculpture (BOZAR) is currently showing a retrospective of the Italian modernist Giorgio Morandi, in which your paintings have also been included. There was a discussion held in connection with the exhibition – “Talking about Giorgio Morandi”. What did you speak about, and what does Morandi's art mean to you, personally?

This retrospective has been curated by an expert on Morandi – the Italian curator Maria Cristina Bandera. Among other things, the exhibition shows that even though Morandi was seen to be a master of still-lifes, he didn't paint only those. Still-lifes are only a part of the artist's work. He also painted self-portraits and landscapes. This exhibition reveals this diversity for the first time, allowing people to observe his evolution.

Also represented in the exhibition is Morandi's phase of metaphysical painting (Pittura Metafisica, 1918-1922), as is his joining of the German New Objectivity Movement (Neue Sachlichkeit) between both World Wars, which he also lived through.

A huge question mark appears here – what was Morandi's position in relation to the fascist regime in Italy? It's always been presumed that he was sympathetic to it, but that is not completely clear. More likely, it could have been a form of political escapism.

That was one of the subjects we discussed.

Since Morandi is still able to influence today's artists, including me, Mrs. Bandera asked me to share five of my works in which a link to Morandi's works could be seen. And the writer Joost Zwagerman has written a lot about Morandi. So, that's how we brought Morandi's idea about silence to the forefront. What did it look like in his works? And, of course, about Morandi's paintings themselves – he practiced a very enigmatic form of painting.

Luc Tuymans. Still Life. 2002

For you, contemporary art is mainly a form of expression in which to reveal the most salient occurrences in contemporary life. An exception is your latching on to a more meditative theme, in which you created your famous “Still Life” (2002). What was the motivation behind creating this piece?

Still Life (2002) came about shortly after the 11 September, 2001 terrorist attacks on the US. My wife and I were in New York at the time – we were really there and we experienced that atmosphere. I saw how the planes hit the Towers from all possible points of view.

The documenta exhibition was nearing, and I started to think about how I could make an answer to this terrible thing – what is it that I should paint right now... I came up with an idea that was completely opposite to the socio-politically acute events of 11 September, and to what was expected of me in the exhibition. I chose to go the way of something totally idyllic, something calming, something that didn't have the slightest thing to do with the Twin Towers. The painting is actually quite ironic. It kind of imitates Paul Cezanne's work, and modernism, as such. Concurrently, it is my own still-life, and as everyone knows – in the hierarchy of painting genres, still-lifes are on the lowest rung. In response to this, I created this painting in a gigantic format (347 x 500 cm). It's impossible not to notice it; it's not even possible to take it all in.

Are there other still-lifes among your creative works?

Well, maybe kitchen of a Los Angeles serial killer could be seen as a still-life. Intolerance (1993), which is in the Morandi exhibition right now, could also be a still-life.

And even if they are still-lifes, they contain a slew of iconic, meaningful and ambiguous elements. In that way, I differ from Morandi.

You, as an artist, pay a lot of attention to other artists. You are also an experienced curator. What is it that links you to other artists?

I've curated eight exhibitions in total. But I'd like to say that none of them were done at my own initiative. People asked me to do it. The latest and largest project was “Luc Tuymans: A Vision of Central Europe. The Reality of the Lowest Rank” – an exhibition in Bruges that I was asked to do by the festival organizers of the Brugge Centraal. It was a parade of Eastern and Central European art – from WWII to the modern day. Along with the Polish artists Miroslaw Balka and Pawel Althamer, American artists were also shown – Andy Warhol, the son of Slovak immigrants, and the artist Alex Katz, who is of Russian-Jewish ancestry.

For me, it's interesting in the sense that it is a possibility to work with art that I haven't created myself. The opportunity to work with notable artists who are still alive, and whom I know personally, is exciting.

When curating, if I speak as an artist to another artist, it's possible to get the project moving forward much faster than a professional curator could. If the artist in question is even interested in the project, than a much higher return can be expected from him in terms of cooperation – that's on the level of solidarity among colleagues.

The reason why I involve myself in these sorts of projects is also due to my observation that, in a large number of exhibitions that have been organized by curators, one can sense the one and the same discourse – which seems to have been pounded into all of the curators during their study years. A kind of pseudo-intellectualism. The exhibitions they make are more documentary than visual. And in terms of curating exhibitions which are based on a look back into art history, they are often created from only the visual viewpoint – not from the artistic viewpoint.

You are well-informed about what's going on. But there are artists who maintain that they never watch TV and that they don't go to the shows of other artists – so that they don't pollute themselves and they can retain the ability to think only about their own ideas. Do you look upon them as real representatives of contemporary art?

I think that's foolish. It's the same as saying that you're against the new mediums, and that you will fight them. That's impossible!

I think that you have to include these opportunities and knowledge in your arsenal of instruments.

And then there's always been this foolish discourse on authenticity. In my case, it's about how I use the new mediums in my works... Stupid!

We can paint by following a certain movement, we can also develop our individual style – which, in my opinion, is rather dangerous – but the most important thing is the meaning that we create in our works. Everyone can use the possibilities offered by today's technologies to create their own images and meanings. Because, in my opinion, art cannot be created from art. It is created from reality. The reality in which we live, the reality that has been created by history. They are connected.

If people are talking about Belgium and they're thinking about art, they always think about James Ensor and his grotesques, and René Magritte as a surrealist. But Ensor wasn't a master of grotesques, and Magrite wasn't a surrealist. They were realists.

People forget that realism has had a special place in Belgian art history since the time of this region's most influential artist – Jan van Eyck. He was the first one who finally broke away from the exact copying of images and the religious dogmas of the Middle Ages. He created realism from reality, by portraying the truth.

This country has been under the rule of so many foreign powers that there has never been room for romanticism here.

And that only strengthens my belief that art is created from reality, from what you experience and see.

Sometimes, one needs quite a bit of knowledge and background information to understand your works. What if your audience isn't in possession of this?

When I began to show publicly, I thought that it was important to supply the audience with informational materials. The journalists were especially happy about this, since then they always knew what to write about. Until it went so far that people began to think: if Mr. Tuymans hasn't spoken about this piece, then you can't even look at it.

Now I am certain that it isn't necessary to know everything – you just have to look. I don't want to encourage everybody to see the same things that I have seen, what was important to me. A work must be multi-layered, it must have room for people's interpretations. And the piece's visual aspect must come first.

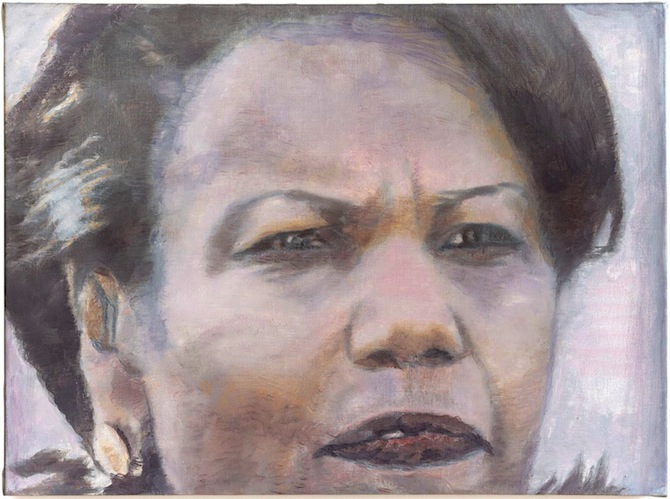

When the painting “Mwana Kitoko: Beautiful White Man”, which was a portrait of Patrice Lumumba, was first exhibited in New York, African-American society thought that it was a portrait of Malcolm X – a passionate defender of minority rights in America. But when the Guggenheim was interested in acquiring the piece, they wrote in their e-mail that they very much like the work with the man in the white uniform – Augusto Pinochet... In Belgium, everyone knew who the person in the painting was.

There was a sort of link between Malcolm X and Patrice Lumumba – they were both linked by power, which was symbolized by a uniform, they were both black, both were murdered.

I'm happy that the painting has made people think on an individual level, instead of pointing out what is what.

I also don't completely believe that it is possible to create universal images. Perhaps Morandi tried to do that, but I don't think that's possible.

When I created the portrait of Condoleeza Rice (she was still the Secretary of State at the time), people interpreted it as my critique of the Bush administration. From my viewpoint, that's what it was, but on the other hand: we're talking about a fascinating woman – the first African-American Secretary of State – a strong, intelligent persona. While some interpreted this portrait as a critique, others saw it as an iconic tribute to Rice – similar to Warhol's Marylin Monroe.

Luc Tuymans. The Secretary of State. 2005

How do you, yourself, feel in front of your works?

All of my pieces are created in one day – I paint fast; that necessitates concentration. When the piece is done, and I feel that it is has been done successfully, I go on to the next one. But before I begin to paint something, there's a long and quite painful thought process – until I arrive at the point where I know what I want to paint and how. My works include both brain- and hand-intelligence.

I don't have a single piece of mine in my house – I couldn't stand it. If I see my work in a museum collection, among the works of others – fine; but if I'm in the dining room of a collector, and my painting is the only one on the wall – I will turn my back to it. Because I always see mistakes.

Is it easy to speak about your work? And does the telling change every time, depending on who is listening?

I am not my art work. What I say is only that what I say. Those are two different things.

Does being a famous artist mean that people really understand your art?

No, not at all. And overall – there are so many people who buy art for the wrong reasons. But contemporary art now is so expensive that only a select few can afford to acquire it.

Another important thing that I'm trying to work on with my dealers – Frank Demaegd, with whom I've worked for 27 years in Antwerp, David Zwirner, with whom I've worked for 20 years in the US, and Kiyoshi Wako, with whom I've worked for 17 years in Tokyo – we try to hinder and discourage profiteering in the art market by buying back pieces from auction houses and controlling prices that are inappropriate for their quality. It is important to steer pieces towards collections in public museums or fund-collections. In America, there are eleven museums who have from one to three of my works, and who travel across the globe with them.

Of course, I work with private collectors, but I always follow along to make sure that they are trustworthy. That's why I don't like to sell to Russian collectors, and the same goes for the Chinese. There's always something to think about – will there or won't there be a speculative maneuver again...

Luc Tuymans. Gaskamer. 1986

What, in your opinion, are the mutual responsibilities of the artist and the gallerist?

It's difficult to follow everything that's going on in the art market. That's why I need someone trustworthy – a consultant from the same Russia or China – who can help me find the path to the right people, to those who are really interested in art.

That's why an artist needs dealers and gallerists, because it's not possible for him to control everything. And I've been lucky with having trustworthy people in my longterm cooperations, who not only sell my work, but also protect it. There are people who don't do this, and who only do cold-blooded buying and selling.

The art world underwent a stark change when the art market – as we know it now – was established in the mid-80s in New York, which was flooded with Japanese yen at the time. The bubble burst, of course, but the machinery continued to churn on. The new generation of artists joined in, and now this system has become a gigantic business. Never has so much money been spent on art as in the last 15-20 years.

The art market is similar to the diamond market – they are both largely based on trust. If you loose it once by doing something wrong – you're out of the game. This same principle applies to the art market, even though it's full of speculators. Because actually, you're buying and selling air – symbolic capital. A diamond is also judged by such qualities as clarity, color and cut – it's value and worth is in the finishing/creative process.

How do you see the future of the art market?

If people continue to invest at the same rate as now, then everything will go on. Interestingly enough, even though the world is on the brink of a gigantic economic crisis, the art market certainly isn't.

Even though there's constant talk that painting is a dead medium...

I think that this talk has been borne from misunderstanding. From the mistaken interpretation of some critics' writings.

When we talk about progress, we're talking about new and newer mediums, which can make it seem as if the oldest of them has died – but that's not true. We use a medium because of the medium – because of its characteristics. In order to create meaning. If a medium is used correctly – everything is alright. Even if it's the same painting. In this case, painting can still create meanings.

After touring in several American cities, my first retrospective in Belgium, in cooperation with the Francisco Museum of Modern Art and the Wexner Center for the Arts, was held in the BOZAR center two years ago. It drew 90,000 people. The exhibition of the German Renaissance-era painter Lucas Cranach, in this same venue, drew 80,000 people. This means that the interest in painting is marked.

Entitled, Allo!, the exhibition of Luc Tuymans was displayed at David Zwirner's brand new Mayfair gallery, opened last autumn in London. This was Tuymans's first solo show in London since his 2004 retrospective at Tate Modern. Photo: Stephen White; David Zwirner, London

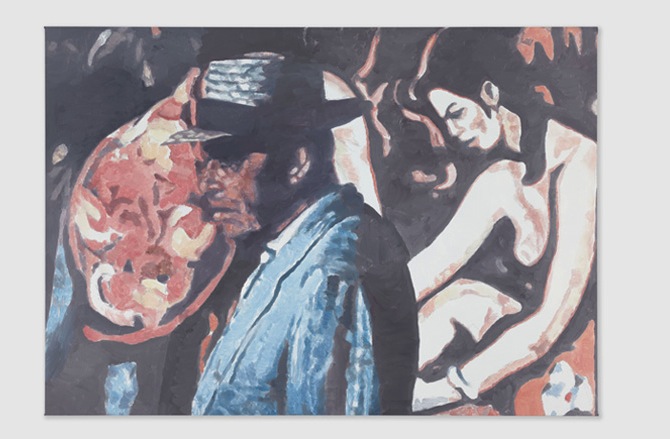

Luc Tuymans, Allo! I, 2012, Oil on canvas, 133.7 x 182.6 cm, Courtesy David Zwirner, New York London

You did leave painting, once. You turned to film. But then you returned to painting...

In the first half of the 80s, I felt as if I were working too existentially in painting, too personally, and it was becoming suffocating. I took a break. By chance, my friend showed me a Super 8mm camera, and I began to film. Indirectly, this experience changed the way that I painted when I returned to it. Very literally – through the camera lens.

How do you comment on the phenomenon when an artist becomes the central persona of an art- manufacturing plant – in which his next “masterpiece” is being created?

I do everything myself. I don't have any assistants. This isn't the kind of art that Jeff Koons or Damien Hirst make. And that isn't the kind of art that I'd want to create. I don't want to criticize – it's just not the way that I work. For me, painting is a very physically present activity; it belongs to a person.

But some art works are so technically complex that their realization requires the involvement of several people. Take, for example, my friend, the Japanese artist Takashi Murakami – I think he works differently than Koons or Hirst. About 250 people work for him. Murakami's hand-drawn sketches are digitally remastered, and then the printed material is silk-screened onto fabric. One image uses 500 screenings, and that's a very technical process. At first, it may seem like very superficial work, but it's not – in Murakami's case, his work is truly a passive-aggressive attack on the West. Unhealed war wounds.

The idea of an art factory was started by Andy Warhol in the 60s and 70s. But if we look even further into art history – Rubens also had apprentices.

Overall, parallels can be drawn between the modern-day art world and that of the Renaissance – Titian was a millionaire, Michelangelo left riches behind, and Da Vinci is seen to be one of the founders of capitalism. In their time, society had influential people who wanted to acquire art with money, and artists who wanted to acquire riches with their work.

It was only in the 19th century that the idea of a lonely and poor artist arose.

Then there were all those people who played that “bohemian shit”... Yes, they came from good families and could afford to do it. Duchamp came from the bourgeoisie, and he could afford to play around his whole life long.

The way an artist has worked notwithstanding – either as a craftsman or as a businessman – he is morally responsible for his work. Both during his life, and after it. He is the one who thought it up and whose thought was realized, and he retains the responsibility for it.

I think that being an artist is also a profession. It is not only a hobby and a dream, and a thing that one likes to do. Today, the creation of art is a complex process that embodies organization – transportation, preparing lectures, printing catalogs. We do all of that here, in my office – a team of several people. Museums should be doing that, but they don't.

Luc Tuymans in his studio. Courtesy David Zwirner, New York London