Narcissus reflected in canvas

An interview with Israeli artist Nir Hod

25/10/2017

New York-based Israeli artist Nir Hod (1970) seems to have found the ideal modern-day formula for fine-art painting. It’s technically innovative, conceptually multilayered and reference-rich, and to top it all off, extremely pleasing to the eye of today’s art connoisseur. It’s contemporary painting. How is it done? By using a high-pressured air gun, a canvas that has been painted with traditional oils and then chrome pigments acquires a particular patina. Something similar happens to virtually anything that has been left outside for a long period of time, exposed to the elements. Once a staple of master painter studios, chrome pigments are rarely used today, and moreover, the deterioration of paint is usually regarded as the greatest threat to any masterpiece. But Hod uses these methods to draw references to art history, and, in the name of staying up-to-date, he also recognizes the vain urges of today’s art aficionados to constantly feed their Instagram alter-egos. Hod allows the viewer to literally enter the painting as they look for their reflection in the chromed surface (a unique experience which must be, of course, saved for posterity via a selfie).

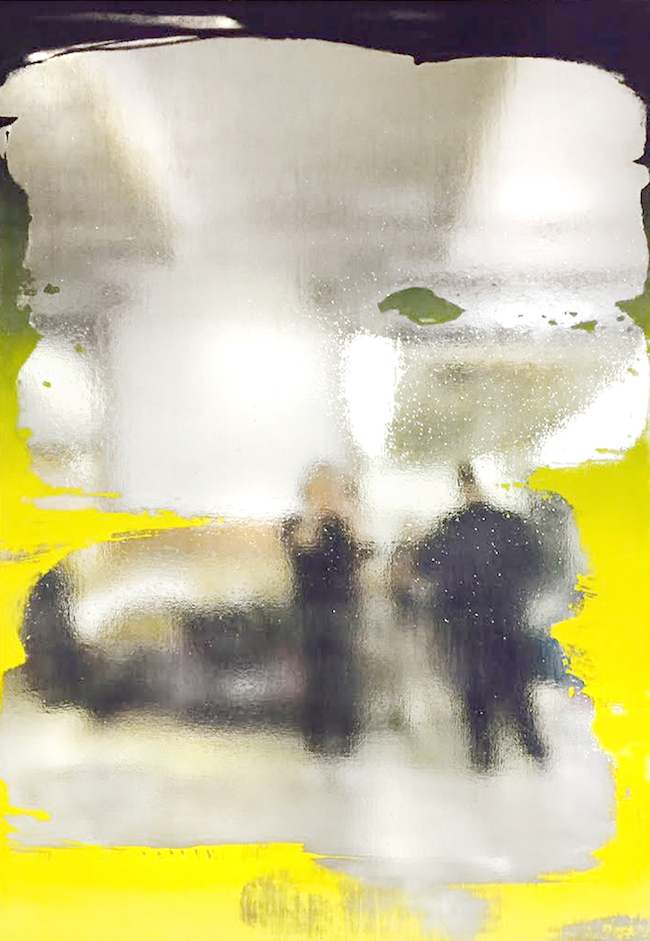

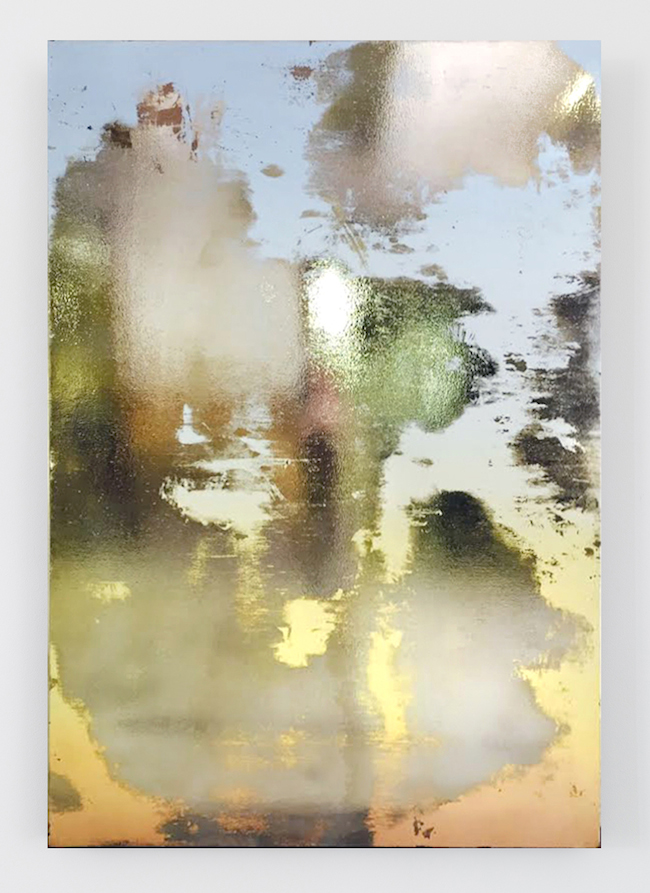

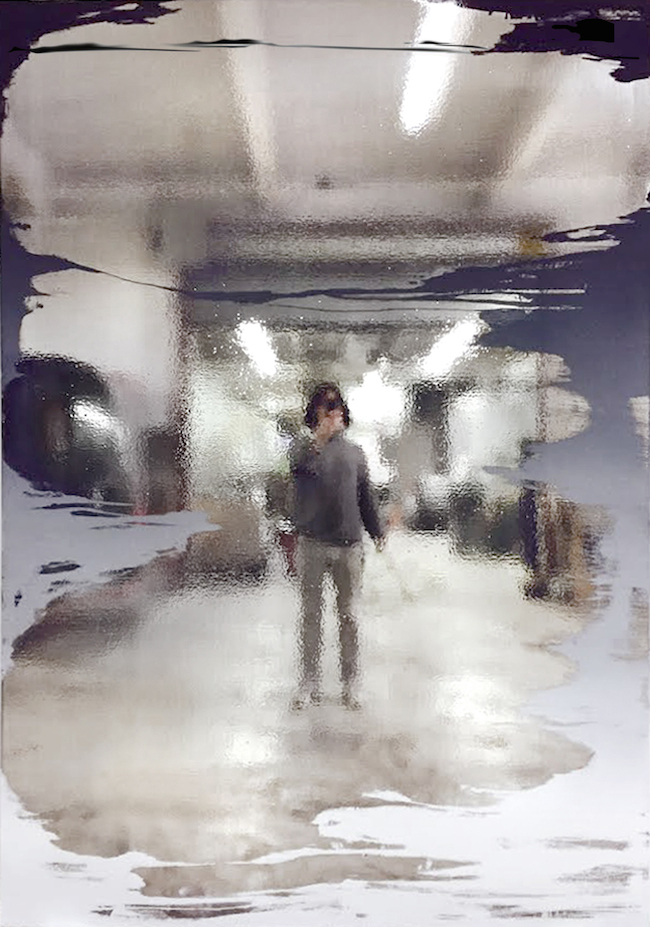

The Life We Left Behind. Oil paint under chromed canvas. 229 x 159 cm

These are the sort of works that make up Hod’s latest series, The Life We Left Behind, which can currently be seen in the Dreams and Dramas exhibition at the forthcoming ZUZEUM art center in Riga. Up to now Hod had been known for his high realism paintings that covered subjects such as beauty, glamor, narcissism, loneliness, and death.

Hod studied at the Bezalel Academy in Jerusalem and at Cooper Union School of Art in New York. He’s had several solo shows, including at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art, the Rosenfeld Gallery in Tel Aviv, the Michael Fuchs Galerie in Berlin, and New York’s Paul Kasmin Gallery and Jack Shainman Gallery.

It was for the sake of his career that Hod left Israel, and now he lives in New York only because of that. What does New York mean to an artist of today, and by the same token, to their career? This is a question that he asks himself daily. He does admit, however, that this city is the place for an artist to be, due to the visual stimuli and inspiration it can give, but also due to “all of the crap it shills out”. When asked about his impressions of Riga, he says: “It’s alive and fresh, yet it still has a romantic air. It has a balance between the past and the future...the proportions are right. Something about it reminds me of Tel Aviv.”

Let’s return to the recent past for a moment… Did you have any expectations about Riga before you came?

I am like a child – in general, I have big expectations from life. That's why I always get disappointed. I live in my imagination, and when you live in your imagination, most of the time there is no connection between your mind and reality. It is so easy to love things in your mind, but it is so hard to love them once you are close to them in reality. In my imagination, I always expect to find love in the places where I go. I really had expectations, and once I landed in Riga, it was almost like going behind a mirror. To forget everything and start to melt into something new.

Tell us about the behind-the-scenes part of your work. How much time do you spend in your studio?

I go to the studio every day, except for weekends. The focus is very important. No matter what the real situation is, I always go to the studio with the feeling that, two days from now, I have two shows opening. I don't know what it is to relax. For me, I can relax for five minutes, not for a whole day or a whole weekend. I don't have a routine because I work on several different things at the same time; I am involved in various projects. I go there in the mornings and just start to work.

Once Every Thing Was Much Better, Even The Future, 2012 – 2013. Plexiglass, stainless steel, 24 karat gold flakes, and mineral oil. Total height: 78 1/2 in. Globe: 40 x 36 diameter inches. Base: 42 x 42 diameter inches

Do you work alone, or do you collaborate with other people?

There are pieces which only I can work on; no one can touch them. But there are individual pieces which require assistance from several people for their execution. For example, at Art Basel Miami 2013, a work from the series Once Everything Was Much Better Even The Future – a monumental bronze snow-globe – was shown in the booth for the Paul Kasmin Gallery. I worked on it for two and a half years, and nine people were involved in its creation.

Other people are involved in the painting with chrome pigments, and there are only a few people in the US who are versed in the technique. You need at least five people to create one chromed canvas. It’s really great that I can work like this because, often times, the process takes up so much time and energy that, by the end of it, you’re just tired and your enthusiasm has waned. But if the idea is being realized by someone else, there’s a whole other energy there. It’s still your work – you have created something great in your mind, using your imagination. In these cases, when I finally see the final product of my idea, I’m as happy as a small child who has been given a present. Then I can also comment on the work completely differently – otherwise it would be rather silly for me to praise how good my own work has turned out.

As an artist, I basically work all day, by myself. There is something almost religious about it, something meditative. I am a victim of my art, and I like to be a victim of my art. I serve my art, and my art serves me. I like to be isolated. When I am doing my art, I am not doing anything else – I don’t eat...I don’t even get hungry. But sometimes it is so nice to go out. To escape your loneliness and to have some people around to share whatever it is that you have in your mind. There always is this conflict. It is almost like functioning as both a nun and a prostitute at the same time.

Genius Christian, 2011. Oil on canvas. 162 x 111 cm

Do you tend to continue working on themes/ideas that you’ve covered in previous works? Or is each series of works a finished and closed creative cycle?

There are so many artists for whom, if you’ve seen a few of their works, there’s no need to see the rest of them. Their ideas and execution always repeat themselves. But I don’t do cheap replicas of myself. I am a thinker, I am a storyteller, I am an image-maker. My artistic contribution is like a film, a book – it’s made up of a number of paragraphs, but at the end it forms one unified whole. The idea behind my work is always the same – it is an interpretation of life and people in a very nostalgic, romantic, sad and painful way, but at the same time, in a very beautiful, seductive way. My work is about falling in love with something you are not supposed to. It's about forbidden desire. And it always has some kind of twist on classical themes, tradition, and icons.

Mother, 2012

Through this twist, I show things as something completely new, something that you see for the first time. My last series, before I started with the chrome paintings, was called Mother. It was based on a very iconic Holocaust photo taken by the Nazi photographer Franz Konrad during the rounding up of the Jews in the Ghetto. It shows Jews being driven from their homes, including a woman, one of many, with her head turned in profile. I isolated her from the picture and, using a Warhol-type of collage format, created ten different images of the woman (or “mother”) with subtle variations in color and lighting. The series before that was titled Genius, and consisted of 98 portraits of children. It was a study on classic portraiture, the subjects, the style, the fashions, and the mindset – a multitude of things that define a portrait as such.

Genius Valentin, 2010. Oil on canvas. 56 x 41 cm

And all of these works examine a dark part of history.

For many years now, since Google appeared, I’ve immersed myself in images. I really like history...I like dark history. As soon as we notice the aesthetic aspect of dark history, a vast territory opens up in which we can better understand how emotions work – both in society and in ourselves. That’s because if we approach it from a completely blank slate, without any contextual information, we are better able to assess the beautiful. There are so many times when you look at something and say: “Wow, this is so beautiful”, but then someone says: "Yeah, but this was taken just moments before the girl’s death,” or “this child is an orphan,” or “this is a forest where they killed two million people," and then you automatically reply: “Oh my God, I can’t believe I liked it”.

It has become something ugly simply because you have become aware of some additional information. But if I like it – it is beautiful; for me, its beauty is the truth.

So I started to look at these kinds of images that appear in dark places – after violent events, after dictatorships, after war, after a very emotional disaster. I found beauty there. Because when you take it out of its context...all those walls, they look so much like Alexander McQueen, Stella McCartney, something between style, fashion. I like this twilight zone of images; you can style them in so many ways. Beautiful children can be like models, but at the same time, they can be orphans, and their beauty can make you feel like you simply want to take them home.

The Life We Left Behind. Oil paint under chromed canvas. 230 x 159 cm

In your new series of works, The Life We Left Behind (and which is currently on view in the Riga exhibition), there are no images of people.

Yes; after Mother, I understood that I can longer work with images of people. Not my own, not those of children, no one. But I knew that I wanted my work to deal with people. [I wanted to work] on the concept of a person who is so tempting that you want to touch them. But they are untouchable, unreachable. I began to think about the meaning of painting today. We live in a time when images are accessible without limits – thanks to smartphones, the whole world is in our hand. In addition, people are obsessed with themselves. Wherever we go, we have to take a smiling selfie of ourselves.

When standing in front of my chromed canvas, the viewer sees only themselves in the reflection. The painting does not exist without the viewer. The viewer becomes a part of it. And people are happy to see themselves in a painting. They see themselves as a work of art. There is something of Dorian Gray in these works...in an interesting, spooky, and very metaphorical way.

The Life We Left Behind. Oil paint under chromed canvas. 229 x 159 cm

Returning to painting… what is painting today? Or, what is contemporary painting? Ever since I came to New York, I’ve been interested in abstract painting and action painting. I’ve also always had an interest in the Old Masters. I understood that I want to find a way in which to combine all of these many narratives, the many maxims of painting, in one work of art. In the Genius series, one could already see how I was intertwining the Old Masters and portrait and family portrait painting. I tried to find a way in which to translate all of this to a canvas which was clean, and how to transform the canvas into a reflective material.

It took almost two years for me to develop this chroming technique. It is done in a spray booth in which the canvas is treated with extremely strong air pressure. As a result, what has happened to the canvas is the same thing that happens to old buildings and frescoes. This artificial treatment speeds up the effect of time destroying the work, and creates a patina. I really like the result because it embodies a lot of elements, from the Old Masters to action painting in the manner of Jackson Pollock. Also, I am dealing with pure chance. These are paintings created randomly; you cannot control the process.

The Life We Left Behind, 2016

If we go back to painting, for as long as I can remember, there has always been an ongoing discussion about the future of painting – Is it alive or is it dead? Is painting experiencing a renaissance?...and so on. How do you see the role of painting in contemporary art today?

Everyone was talking about the death of painting already back in the 90s, when I was a student. Due to technology, video, photography… But nothing like that happened, and moreover, I believe that painting will always be powerful and relevant. If anything, I see the relevance of photography waning as a direct result of good painting. In addition, today, anyone can create a good photograph. But not everyone can be a painter.

This brings New York’s Times Square to mind. With all of its billboards and ads, it’s inspiring, but nevertheless, so very vulgar. You feel as if you were eating junk-food. It tastes good, but five minutes later, you begin feeling ill. The body is not ready to digest it, but your appetite wants more and more. But if you resist this junk-food, and eat only good, healthy food, you will want more and more of the healthy food. The same thing holds true for painting in the world of art. Painting is the foundation of everything. That’s also why my chrome paintings are successful in this era of the selfie. It’s trendy, it’s contemporary, but it’s painting.

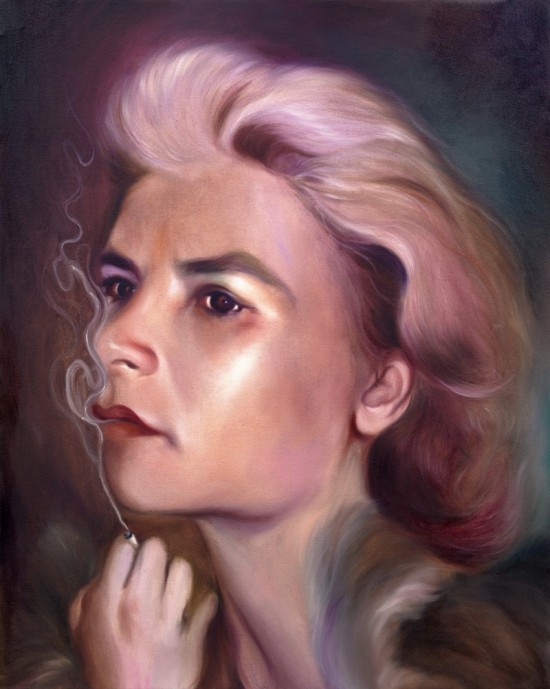

Elizabeth, 2003. Oil on canvas. 310 x 210 cm. From Forever series

What is the relevance of hyperrealistic painting in contemporary art?

Sometimes artists become so enthralled by the technique of achieving a maximum closeness to reality that the message and the concept behind the work disappears. I like realistic painting, but hyperrealistic painting – to a lesser degree. Because even in abstract painting it’s possible to create your own reality. I have proved to myself that I can paint hyperrealistically, which is why I can also break it and deform it. Otherwise, it seems too cold and technical to me. Gerhard Richter inspired me to paint, and he is a realism painter.

What is the relevancy of the titles of your works?

Many artists don’t title their works, but I believe that titles give the work context. They are very important to me. Sometimes it’s even hard for me to work on a piece if I don’t have a title in mind. They appear instinctively. They can be romantic; they can come from the sorts of depths that many don’t want to peer into; they are about the soul, about life’s essence. Sometimes they are very naive, but at the same time, philosophical. They are beguiling – an element of beauty with an aspect of loneliness and despair. They can be interpreted according to how a person sees and understands the world.

When asked about the role of an artist today, you have said that “artists are the soldiers of God... The great artists today are the new teachers…” What sort of a “soldier of God” and/or “teacher” do you see in yourself?

I always have said that art is something very religious. It’s almost like a cult. “Soldier of God” – because as an artist, you never stop working. You’re working with your mind. It’s never-ending. Just like religious devotees who completely give their lives over to a higher power, so does the artist give their life to art. They live according to different rules, and they do everything to encourage people to live a better life, to look at things differently.

Genius Bernard, 2010. Oil on canvas. 71 x 57 cm

You tend to emphasize the importance of narcissism in an artist’s personality...

Yes. All of these years people have told me that I’m too narcissistic, and I always reply that it is great for an artist to be narcissistic. Art is about narcissism; it is about charisma and personality. I’m not saying that I, as a person, am narcissistic, but as an artist – I absolutely am! The best artworks in the world are narcissistic. Of course, there is a price to pay for that – it’s not easy to live with a narcissistic person, and it’s not easy to be one either. There’s always an inner struggle and searchings...narcissists have something like x-ray vision – they can see things that others cannot. If this narcissism is used to do something important, as in the case of an artist, then I think that is wonderful.

The Dreams and Dramas exhibition is a special project for Riga initiated and funded by the Riga-born businessman, collector, and patron of the arts, Leon Zilber.

The exhibition is ongoing at the ZUZEUM Art Centre through November 5.

Exhibition hours:

M: Closed

Tue – Th: 12:00-18:00

F – Sat: 12:00-20:00

Sun: 12:00-18:00

Guided tours:

Sat: 12:00, 15:00 / Sun: 12:00