A story about belonging and not belonging

An interview with Australian artist Imants Tillers

05/02/2018

Imants Tillers is one of the world’s most renowned Australian artists. In the 1970s and 80s he was regarded as a provocative phenomenon on the Australian leading-edge art scene, and that’s how the art world of that time got to know him. Tillers represented Australia at the São Paolo Bienal (1975), took part in Documenta 7 (1982), represented his country at the Venice Biennale (1986), and has participated in numerous other prestigious international projects. He has had shows at PS1 in New York and the Institute of Contemporary Art in London, and has received many international art awards, including the full range of the Osaka Triennale Prize – Gold (1993), Silver (2001), and Bronze (1996); the Beijing International Art Biennale Prize for Excellence (2003); and Australia’s most distinguished award for landscape painting, the Wynne Prize (2012&2013). Tillers is also recognised as a prominent intellectual in the fields of art theory and curating.

Today Tillers’ conceptual quintessence encompasses a range of subjects: the relationship between ‘the province’ and ‘the centre’, and the search for a sense of identity and belonging; the capacity, processuality and mutual influence of the cultural space; and the presence of historical phenomena and events in today's world. Painting is what Tillers focusses on now, and it seems that he has become more emotionally sensitive as compared to his early career. Back then, in the 1970s, he was described as a marked conceptualist who, above all, was interested in art as a phenomenon and a process. ‘In the seventies, it was more about art ideas. My art was a quite complex thing with many parts. It was never just a painting. Even though I used painting, it was more of an installation or even sculpture sometimes.’

Imants Tillers. The Nine Shots, 1985. Synthetic polymer paint on 91 canvasboards, nos. 7215 - 7350 330 x 226 cm. Collection: National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

An enduring mark of Tillers’ art has been the use of quotes, references, and appropriation. He has never been afraid of borrowing characters from others; the works and texts of others have been a notable conceptual starting point – a base upon which he builds and develops his message. At the 1986 Sydney Biennial, Tillers exhibited his work The Nine Shots, in which he used images taken from the painting Five Dreamings by Aboriginal artist Michael Nelson Jagamara. Tillers was unprepared for the resulting accusations of copyright infringement and appropriation of Aboriginal imagery since, up to that point, citing others had been a common method and regular instrument for him. Tillers says that after the incident, he didn’t want to engage much with Aboriginal art. However, something rather unexpected happened fifteen years later – Imants Tillers and Michael Nelson Jagamara became partners in the creation of large-format paintings. Trusting and supplementing one another, a series of canvas boards (much like the pieces of a jigsaw puzzle) travel from one artist to the other, and, in the end, are joined together to create one large-format artwork. It turns out that this piecemeal method of connecting an impressive number of canvas boards, which immediately brings to mind the above-mentioned jigsaw puzzle, arose from both the wish to expand the boundaries of painting and, for practical purposes, to simplify the logistics of transporting large-format paintings from Australia to other continents. Today, this ‘puzzle-effect’ has become a specific idiosyncrasy of Tillers’ oeuvre.

An important touchstone in Tillers’ life was the year 1990 when, far away from Australia, on the other side of the globe, the Soviet Union broke apart. This child of Latvian WWII refugees, and who as a young man had decided that he would distance himself from his ethnicity and simply be an Australian, suddenly saw the return of a place called Latvia on the map of the world. ‘There was no place called Latvia because it was in the Soviet Union. The [political] changes changed my orientation, and I thought about diaspora and identity, and history. It actually gave me a new kind of content and it brought more emotion into what I did.’ Today, Imants Tillers recognises himself as a member of two cultures.

Arterritory.com met with Imants Tillers in Riga, at the Latvian National Museum of Art, which in July of 2018 will present a broad retrospective of Tillers’ work titled Ceļojums uz nekurieni / Journey to Nowhere. ‘The exhibition in Riga is a tribute and testament to my parents, Imants and Dzidra, who arrived in Australia as “displaced persons” in 1949 on the Dutch ship Volendam after the longest journey of their lifetimes. I was born the following year, in 1950, in Sydney. My exhibition, indeed one could say my work, is all about “belonging” and “not belonging” – about relationships between a “fatherland” and its diaspora. In many ways, this is almost the universal leitmotif of the 20th century. Much of the contemporary world, at least what is called “the new world”, is populated by the descendants of refugees and immigrants, most notably Australia (let’s forget about the convicts, but never forget the collateral damage done to the Aboriginal people!).’ This is how Tillers commented on the forthcoming Riga exhibition in November 2017, at the opening of his show at Sydney’s Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, which included one of the pieces which will be on view in Riga. In fact, the piece is titled exactly the same as his upcoming solo show in Riga, Journey to Nowhere, and is a pronounced concentration of Tillers’ conceptual and formal thinking. At 229.5 cm x 356 cm in size, this classic view of the Riga skyline (a postcard shot which most every Latvian living in the Soviet era had sent to their friends and relatives in the West) consists of 90 painted cardboard panels. Text overlays the image; or more precisely, phrases overlay it. Upon googling the boldest, and perhaps most emotional, phrase – ‘We have decided not to die.’ – the top results reference a 12-minute Australian short film with the same title.

.jpg)

Michael Nelson Jagamara and Imants Tillers. Metafisica Australe, 2017. Synthetic polymer paint and gouache on 72 canvas boards, 245 x 285 cm.

You are one of the world’s most famous Australian artists. Yet you are a first-generation Australian since your parents were Latvians who fled from the Soviet occupation. Does this European background have any influence on your life? Do you sometimes feel as if you are European?

Maybe I feel European because I don’t feel fully Australian sometimes. I think it’s very positive to feel a bit European because Europe has such a rich culture. And Australians… I guess they relate to the UK and a bit to America. But... the British look down on Australians.

They look down on everybody.

But especially on Australians [laughing]. There was a show at the Royal Academy called Australia in 2013. It got very bad reviews in the UK, and that’s because they still look down on Australians. Australia was a penal colony where they sent their convicts; maybe it’s still like that somewhere in their memory.

We first met during the Venice Biennale. There are a lot of issues that come up with the subject of the Venice Biennale and its national pavilions. In 1986 you represented Australia there; is it even possible to talk about national art in today’s world, one in which globalisation plays such a strong part?

That’s a difficult question. From the beginning of my career, Australian artists – my whole generation – wanted to be international; they didn’t want to be Australian. But in this global art world, internationalism has changed its nature; it’s has taken on a duality and now it has a completely different context. I think that, at this moment in time, it’s important to have strong links to Australia, because otherwise you’re just a part of this ‘sea of art’. We now have museums in Australia which exclusively collect, for example, Chinese art. Suddenly, internationalism means that you’ve become diluted in your own country. Collectors now want to purchase international art (whereas in the past they wanted to buy Australian art), so now, even at home, you’re competing with the stars of the international art world; in a way, you can be marginalised in your own country. I think what is important is to maintain some sort of a connection to your place. Maybe you don’t want to call it Australian art, but you want to have something unique which comes from where you live and your cultural background. You don’t want the world to become homogenised. We have a museum in Hobart (which is in Tasmania) that has been set up by a private patron, David Walsh, called MONA (Museum of Old and New Art). He collects some Australian art, but he also collects Christian Boltanski, Anselm Kiefer, Jannis Kounellis, Damien Hirst – all of these big names. It’s great to go there and see these works, but... I think there needs to be a bit of a balance in which you don’t kill off the local artists. Of course, I think that ambitious Australian artists would still like to belong to the international pantheon of significant artists, but I think it’s actually hard to achieve this. There are a few [Australians] who’ve had international art exhibitions in New York or London or elsewhere, or who have been in museum shows, but people still find Australia as a bit of a blank spot in terms of contemporary art; and really, it’s Aboriginal art that people think of when they think of Australian art.

How would you characterise the Australian contemporary art of today?

Well, I think it would be hard to differentiate it from British contemporary art or American contemporary art. You know, people are working in the same modes: video, film, installation, sculpture, painting, and there isn’t much to differentiate it from art originating elsewhere. Maybe Aboriginal art, in some way, or aboriginal issues make Australian contemporary art something unique, you know, for those outside of Australia. That’s what I partly try to engage with as well. This kind of combination of an ancient tradition and a contemporary tradition doesn’t exist in many places in the world. I think that for Australians, that’s kind of a unique and positive situation.

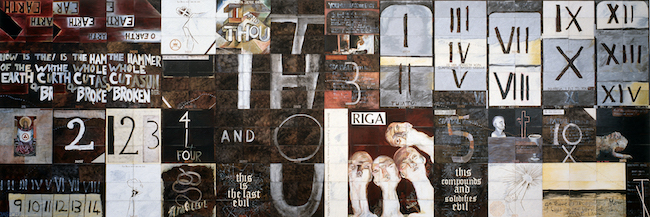

Installation view of Tillers’ exhibition at Matt’s Gallery, London in 1983

And you have had a relationship with Australian Aboriginal art for a very long time…

Originally, it was because I was interested in quotation and appropriation, and I did reference some Aboriginal works in the same way that I did other works. It was a bit controversial because Aboriginal artists were not part of the contemporary art scene at the time...so they were a bit angry at that, a bit shocked, that someone else had done that with their images...yes, I certainly got into a bit of trouble. [Chuckles] In later years, I developed cooperative relationships and many things changed.

But how did you first find out about Aboriginal art? Do you remember that moment?

Yes! It was quite exciting because this Aboriginal art was something new. I mean, Aboriginal culture is sixty thousand years old, but most of the culture’s manifestations were rather transient – they would paint their bodies or paint the ground for ceremonies, and then when it was finished, it would all disappear. But then in the early 1980s, in Papunya (which was like a displaced persons camp) there was this school teacher named Geoffrey Robert Bardon... Do you know about this?

The government set up these camps for the Aborigines, right?

Yes; the government brought in people from different tribal groups, and they were all in the same place. Some of these people came from really remote areas and had not had any contact with white people before. Also, having different tribal groups in the same area is not necessarily a happy place because they had different languages and different cultural traditions. It’s like if you put Latvians, Czechs and Russians in the same camp [chuckles]. And some of the elders were worried that their culture was not being passed on to their children and younger people, so Bardon, the schoolteacher I mentioned, had the bright idea of getting them to paint their stories on the walls of this school in Papunya. From that, he got the idea that they could paint their stories in permanent materials on something like boards – so instead of disappearing, they would stay there and be seen. And that was really the start of a new art movement, one in which Aboriginal culture is actually manifested in a permanent kind of way. That happened in the early 1970s. I became interested in Aboriginal art in the 1980s, around ‘81, ‘82. Initially, mainly through an artist,friend Tim Johnson, who had started visiting this place and had begun to paint them(depicting the artists with their paintings in the landscape), and who also liked collecting their work, which he did with his wife Vivien, and then eventually donated to museums. So that’s when I first learned of it, and I thought that it was something quite amazing. The images were quite amazing. I mean, now we are very familiar with the symbols and what they might mean, but initially, it was something completely new, and... I felt it was very kind of conceptual, also. These weren’t just attractive patterns. They actually had quite specific content and meaning. As someone who had come from a more conceptual background, I found it really interesting.

In 1986 you created The Nine Shots, which was exhibited at the Sydney Biennial and then elicited the scandal that you mentioned. You had appropriated images from Aboriginal art, referenced them without permission. Did you meet with Michael Nelson Jagamara – the artist whose works were at the core of all this – at that point, or only many years later, when you began to closely collaborate with one another?

Yes, I met him at the Biennale opening. On being shown the catalogue, he recognised his painting as being jumbled up in mine. He was polite and did not seem angry — however he thought I should consult and seek permission next time. Immediately after this controversy, I didn’t want to engage with Aboriginal art all that much [chuckles]. So I looked at other things. But in 2001 I had been engaged on a sculptural project, and I remembered that I had seen in a magazine some sculptures by that same artist, Michael Nelson Jagamara. I contacted him through his gallery, and thought that maybe this project could involve some of his sculptures, but it didn’t happen. However, his representative, Michael Eather of Fireworks Gallery, Brisbane, suggested that I bring him some canvas board panels and show him how I work on these panels, and that we might do some collaborations. So it kind of happened through a third party…

So he painted on these canvas boards?

Yes. We began to collaborate. But I only went to Papunya for the first time just recently.

And what was your first impression of the place?

Well, it’s quite remote [chuckles]. It is the most remote point from the coastline on the Australian continent.

There must have been about sixteen people at the house when we arrived, but anyway, Michael Nelson Jagamara was very pleased to see us. There were sort of these ‘dreaming’ sites nearby. ‘Dreaming’ is actually quite a hard concept to grasp in Aboriginal culture. It’s more than mythology. It’s kind of like a reality… It’s kind of like their perception of the land. It's a story that explains the creation of the land, the people, and the animals. It goes back sixty thousand years, but it goes back with information and songs that are passed on from generation to generation. So these places are, I guess you could say, places of power. For instance, one is called The Honey Ant Dreaming [this is depicted in a mural painted on the outer wall of the school in Papunya – ed.]. In the real world, honey ants are how the Aborigines gather sweetness – the ants have huge abdomens filled with real honey. But ‘dreaming’ isn’t really about animals like the wallaby or the kangaroo, or lizards, snakes, or honey ants, but more about what they really mean. It’s kind of like a supernatural being called ‘the honey ant’, or a supernatural being called ‘the wallaby’. So, somehow, these spirits are embodied and connected to particular animals, but the stories are really about the creation of the world. I think it’s quite metaphysical, but maybe also spiritual. But for them, it’s a kind of reality. If you break the rules, there can be serious consequences. There are these various rules, such as women mustn’t see certain ceremonies or objects and vice versa, and there are certain things they have to do, and if they don’t do them, they get punished. Maybe even by death.

Imants Tillers and Michael Nelson Jagamarra. Fatherland, 2008. Synthetic polymer paint, gouache on 90 canvasboards, nos. 228 x 356 cm. Private Collection, Brisbane

Is Jagamara deeply involved in this culture?

Yes, he is truly involved (he is a respected elder responsible for initiations and enforcing Aboriginal law etc. in his community) which may seem unusual because now he is quite famous. He has had quite a lot of opportunities in the West; for example, for the opening of the new Parliament House of Australia, he was commissioned to design the extensive forecourt mosaic. He met the Prime Minister and the Queen when she came out to open the Parliament House.

Nevertheless, he continues living his life the way he always has.

He does, yeah. He has also travelled to London and New York, so he has become a bit more open to the West. He probably wouldn’t have collaborated with me if he had not had those experiences, but now he thinks it’s okay to work with someone like me. In fact, he also did one of those BMW Art Cars.

That’s wonderful!

Yes, Michael Nelson did one. He has...not quite a manager, but a person whom he hires (Michael Eather) to represent him. That’s how it even became possible for me to work with him...but we don’t actually sit down and say ‘So, what are we going to do?’

So how do you do it?

Well, it was more like, I start by doing some panels with some text in them, and then he would paint over them, and then maybe I would finish them. But we were not working in the same place.

You just sent him these panels?

Yes. Before my trip to Papunya, he had been in Brisbane and had painted some panels for me to work on. Now they’re in my studio in Cooma, with me. I could do anything...I could paint it all out if I wanted to. So our collaboration was based on trust; I would respect what he had done, and vice versa. There have also been works where he sort of started everything, and then I had to kind of respond. So we really connect in the painting, but not so much personally. Because there’s still a huge difference between us, I mean a cultural difference. But anyway, it has kind of become a friendship through this process.

Michael Nelson Jagamarra and Imants Tillers at Papunya, April 2017

A friendship without verbal conversations or words, but rather conversing through painting and drawing…

Yes, exactly. I feel very privileged. But that’s not the totality of what I work on. However, once I started these collaborations, I became more comfortable when referencing Aboriginal culture. You know, there were originally over 400 different Indigenous nations within Australia, so I did two major works about that - Terra Incognita 2005 (which is in the collection of the National Gallery of Australia) and Terra Negata 2005 (which is included in the exhibition Journey to Nowhere at the Latvian National Museum of Art). I don’t think I would’ve had the confidence to explore these things if I hadn’t been working with Michael Nelson. A lot of the restrictions about this kind of interaction are not made by Aboriginal people but by white people – academics or critics or people who actually manage the art cooperatives because they’re concerned about the Aborigines being exploited. But once you’re in this process, you realise that they’re more laid back about it than you had imagined. With Michael Nelson, I also wanted to have a finite time in which I would work with him, but evidently he keeps saying to his home gallery: ‘When is Imants going to send me more panels?’ [Chuckles]

Let’s talk a bit more about your artistic career...you started with Christo, which is really impressive. Was it Christo who inspired you to become an artist, or was it just a coincidence that you met Christo? You were a student of architecture at the time, after all...

I think it was more of a coincidence. In Australia, it’s a bit like – everyone is an artist. For example, in the “Latviešu nams” [the local Latvian community centre – ed.] there are exhibitions featuring young people; I mean amateurs. [Chuckles] So now I think: Maybe I was always an artist?

I was just very fortunate that Christo’s Wrapped Coast took place in the first year of my university studies, which were in architecture. We had a couple of tutors who had just come from Berkley in the US, and they were very open about changing the architecture course of study in Sydney. They thought that it would be a good experience for some of the architecture students to go work on this Christo project – there was this fabric that needed to be affixed to rocks. It was quite a large area of coastline, so Christo needed a workforce; some were paid, but we architecture students could work on it instead of doing a required design component. There were around ten of us. During the process, I met a young artist Ian Milliss who was already exhibiting in serious contexts, and he was only 18 or 19; we were friendly, and he said: ‘You must subscribe to Art Forum’ [chuckles]. This was in 1970. So I did. I began to read Art Forum and I started to develop an interest in the avant-garde, minimalism, conceptual art. That became my focus then, and I was probably quite a quick learner. In Australia, there weren’t many opportunities for young artists, but they had something called the Contemporary Art Society, which held two exhibitions a year – one for young contemporaries, like young emerging artists, and one for older artists. That was where the more progressive art was being shown in the seventies.

Imants Tillers. Conversations with the Bride, 1974-75. Gouache, synthetic polymer paint on paper, type C photographs, aluminium dimensions variable. Collection: Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney

In the 1970s, you were a pronounced conceptualist – the most distinct example of your art and thinking at the time would probably be the installation Conversation with the bride, which is in close dialogue with Marcel Duchamp’s The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even. But now when I look at your landscapes, I see the same artist but more melancholic, more spiritual. How did this happen? What caused you to change in this direction?

Yeah, that’s a good question. In the seventies, it was more about art ideas. My art was a quite complex thing with many parts. It was never just a painting. Even though I used painting, it was more of an installation or even sculpture sometimes. Then, in the 80s, there was this return to painting internationally, which was also kind of exciting. So instead of just doing one self-contained work after another, I started working continuously. As part of something that’s also conceptual but… not everything needs to be impressive or large. Also, I was attracted to neo-expressionism (Kiefer, Kirkeby, Schnabel, etc.), and at the same time, I was attracted to the opposite – to un-expressionism, which was like a critique of expressionism. Somehow I was able to do both, in the sense that I started to quote expressionist painting but with the quoting itself becoming a kind of critique. When I was able to start showing in New York in the mid-1980s, for example, critically I got one very bad review from Donald Kuspit, the biggest defender of neo-expressionism. And it was fantastic! Because that’s how people persuaded me to cross over to the opposite camp [laughing]. There was definitely a struggle going on in New York, and elsewhere too, between these two impulses. Actually, now I realise that the fact that expressionism caught my attention could have been the impetus for me to continue painting. Maybe those were my Latvian roots and their link to everything German...in my subconscious...which drove me to expressionism. But in the 80s it was all about appropriation and deconstruction. A kind of critique, a part of which was the fact that Australia was like a second-hand culture where everything came second-hand. We had the same art movements but they came a bit later.

The relationship between ‘the province’ and ‘the centre’.

That’s right, as we were very much a province. My idea was, partly, that you can make your art from this dilemma, by embracing the dilemma and saying – it’s all second-hand. In fact, that was something that was being recognised outside of Australia – that all this Australian art is trying to make a virtue out of [the country’s] distance and provincialism.

But then, I guess, a turning point really came with the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1989/1991 and the political change actually struck me quite strongly, because growing up in Australia, when you said you are Latvian, people would look at you blankly and say ‘there is no such country’ [chuckles]. There was no place called Latvia because it was in the Soviet Union. The [political] changes changed my orientation, and I thought about diaspora and identity, and history. It actually gave me a new kind of content and it brought more emotion into what I did. And trying to make connections between different sources that weren’t just arbitrary; it wasn’t just about the art world anymore. It was more about… the fact that you have a link, a connection to a place even though you have grown up and spent your adult life elsewhere. In a way, maybe the attraction to Aboriginal culture is that they’re very much suffering the consequences of colonisation. So, I think it has given me more depth. But I use the same processes.

It seems that in your art, along with the conceptual position and the layering of content and emotions, just as important are the formal methods of expression. At least the painterly surface of your work indicates that...

In a way, I think that goes back to choosing the canvas board as a way of producing work. Initially, part of the reason I thought of it was due to transportability and working with minimal resources. You could produce large-scale works.

Imants Tillers. Diaspora, 1992. Oilstick, synthetic polymer paint, gouache on 228 canvasboards, nos. 34000 – 38183 305 x 915 cm

Approximately how many of these smaller elements make up one work?

I started with about fifty elements, and soon produced paintings that had maybe a hundred and seventy panels, so they were around 3x6 metres in size [Tillers has since produced a series of 10 monumental paintings consisting of 288 panels each, the first of which was ‘Diaspora’ 1992, exhibited at the Latvian National Museum of Art in 1993 - ed.]. So they were around 6x3 metres in size. The first solo exhibition I had overseas was in London at Matt’s Gallery and I basically showed two paintings which were a hundred panels each. I sent them by post…So it was a way of actually participating in this new moment without having too much of a disadvantage. I mean, there is a lot of disadvantage, but you could still do large-scale works and they could be transportable. So that was initially the reason, but I think that as I kept using this format, I kind of discovered what you can do with this new material. For example, you can, if it’s a hard surface, draw on it, press on it. Initially I used charcoal and a pencil and paint. I started to kind of reinvent painting for myself. Like a child, you know? [Chuckles] Then I began to develop some complexity and started to use layering; I sometimes used my old works as an under-layer for the next work. Now I use masking tape and cutting with a scalpel because you can cut into a panel, whereas you wouldn’t be able to cut into canvas. So, this layering process has become something that’s developed from working with the canvasboard as a ground and which I like now because it gives a complexity to the surface… it’s really about making all these little discoveries about how you can work with it.

Imants Tillers. The Blossoming Tree, 2017. Synthetic polymer paint, gouache on 54 canvas boards, no. 98784 - 98837 228.5 × 213cm

An important component of your art is the presence of text.

Yes, but that’s also more recent. I’ve used texts for maybe the last 20 years…They’re more like visual poems; the text and the image interact with each other, and I like this kind of match. I collect not only images but fragments of text as well. I read different writings, I read authors and poets, and philosophers, but in a very targeted manner…

With the purpose of finding texts you could use?

Yes, very targeted. I’ve had help from a writer friend, the author Murray Bail, who’s sort of mentored my reading. I look for connections. For example, one author I liked very much was Thomas Bernhard, an Austrian writer; in their noble moments, his characters would reference or quote the German poet-philosopher Novalis. So I’ve now looked at Novalis, too. [Bernhard] also references Nietzsche, and I’m quite interested to see what I can find there, so it’s a bit of an informal investigation. One thing leads to another.

Your inspiration appears to come from different sides and sources.

Yes… maybe I find something, maybe I don’t find anything. I certainly can’t understand Heidegger or anyone like that [chuckles], but I do like some of his expressions. It’s not theoretical research; it’s more like intuitive and emotional research. Whenever I’m not in the studio, I take notes about whatever I find.

But you were a strong writer as well. In the 1980s you wrote a lot as an art theoretician.

A little bit. I mean, maybe once every two years or so. I have written a few pieces just exploring different ideas. In fact a selection of my essays are being collated for a book right now which will be published to coincide with the exhibition in Riga. I’ve just written one called Metafisica Australe, which is about the metaphysical nature of Aboriginal art and in which I look for links between the art of de Chirico and Aboriginal culture. But I don’t think that I’m a really great writer. I prefer to be an artist, really.

Imants Tillers. The Emergency of Being, 2013 [Self Portrait]. Synthetic polymer paint, gouache on 25 canvasboards, nos. 92655-92679 150 x 150 cm. Collection of the artist

In the 1970s, you claimed that painting was dead. But now you paint yourself.

Yes, I did say so in the 70s. But I don’t personally agree with that anymore. I think that it’s alive. Now it’s a more complex situation. You could say a lot of installation art is dead, or that video art is dead, because they have the same problem. Not everything is very original. When they say ‘the death of painting’, what they really mean is the death of painting as a kind of avant-garde expression, because painting obviously survives. It’s just that painting is no longer cutting-edge, and painting can’t really take you anywhere different.

We are in a situation where everything is quite dead.

Yes, everything is quite dead [chuckles]. That’s why I actually like someone like de Chirico, because his work is quite complex. I don’t mean that each painting is complex, but his approach to his whole output is quite complex. I think that you can learn something from that now. For example, in his work, time simply does not exist. Because he has defied chronology. He is very well known for his early metaphysical period, but he rejects that and paints copies from Rubens and Michelangelo, and paints still lifes and paintings of Venice. It’s very strange. When you start to see a lot of his work, you can spot this certain moment in which he has decided that he can paint his metaphysical paintings again, like thirty years later. And improve them. So there’s this quite original way of thinking. Now that I’ve done a lot of work, I’m also thinking about how I can connect to the earlier work as well. It’s not always a progression to a sort of climax, like Rothko or others, or a climax to pure abstraction. But I think that is no longer really relevant, because there is nowhere for painting to go after the simplest kind of abstraction, so it has to kind of reinvent itself and make itself more complex again. I don’t think that painting is dead. It’s just that you have to take a different view of how to engage with it.

But that means that everything has already happened. Is the avant-garde no longer possible in today’s world?

I don’t know. Not in the same way. I think that maybe it is no longer possible. The art in the biennials and all these exhibitions that we see – none of it seems avant-garde anymore. There isn’t something exciting and unexpected. The avant-garde sort of stopped at some point. Maybe it stopped in the early seventies, even. I mean, it’s sad, because we would like to have an avant-garde. It would be nice if we could say that, for example, Tino Sehgal or Marina Abramović are today’s avant-garde. But it’s framed by museums; it’s framed by collectors. So it’s kind of not so avant-garde. I mean, maybe it’s avant-garde for people who have no experience of the art world.

Does that mean that if art is being accepted by institutions, powerful money, and the public, it cannot be avant-guard?

Yes [chuckles].

But does art have the ability to change things? Does it have energy?

I do think so because I think that art definitely has an energy. The first time I went to the Van Gogh museum in Amsterdam, which was in the mid-90s, I was overcome with this incredible emotion; it wasn’t an intellectual response, it was just something that happened. I think that when you do see work by a great artist, it can have that effect. An artist needs to see great work, whether it’s contemporary or older, to reaffirm that it’s worth being an artist and that art can be powerful. But I think the trouble in our world is that we see a lot of art which is not powerful and which doesn’t have that energy.

Imants Tillers. The Journey To Nowhere, 2017. Acrylic, gouache on 90 canvasboards nos. 98522 – 98611228.5 × 355 cm

In the spring of 2018, the Latvian National Museum of Art will present a broad retrospective of your art titled The Journey to Nowhere. What is behind that title?

Well, the simple reason is that a friend gave me a book called A Journey to Nowhere. It was written by a Canadian writer, I think his name was Kauffman, and he was in love with a Latvian girl when he was young, in Canada. He was curious to find out where she came from and he came to Latvia just after 1991 and made his way through the country. It was very interesting because he knew nothing about Latvia, which is why it is called A Journey to Nowhere. It’s quite an inspiring book. The way I was brought up, as a child of Latvians, was that being Latvian was the only thing that mattered [chuckles]. I had a very protected childhood, very insular, and very Latvian, really. I was, kind of like, Latvian at home and Australian at school. You become a split personality. But when I went to university, everything changed. I thought: ‘I don’t want anything to do with these Latvians!’ Saying to someone ‘I am from Latvia’ or ‘My parents are from Latvia’, that was kind of like nowhere to most people. But I also thought, to my parents who had to leave Latvia, Australia must have seemed like nowhere as well. They knew about America, but Australia… So, I thought, actually, those are some nice places – from nowhere to nowhere, or from somewhere to somewhere [chuckles].

In which language do you dream? In English nowadays, I suppose.

Mostly, but I have had a couple of Latvian dreams.

Portrait of Imants Tillers by Harry Ho