Julian Rosefeldt – a mysterious discrepancy

In Riga, the author of Manifesto and In the Land of Drought explains: ‘I’m interested in the mysterious discrepancy between what you’re seeing and what you’re hearing’.

20/08/2018

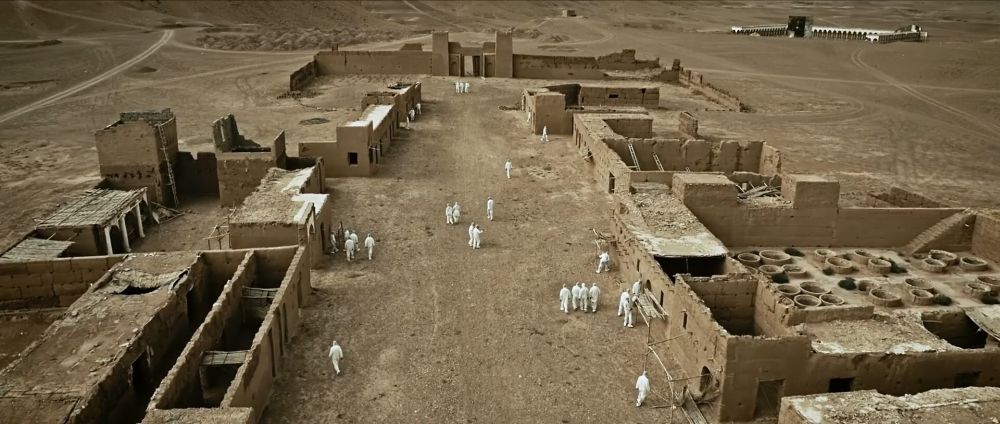

Julian Rosefeldt shows us the world from a completely different viewpoint. At the start of the 2000s, he was already demonstrating with his upwards-sliding camera how everything really isn’t as it appears to be from our accustomed perspective. Shot from above, it showed the ‘lining’, or inner workings, of the manipulative nature of everything that we see (and hear, in regards to his 2004 work The Soundmaker, one part of the Trilogy of Failure series). In his latest video work, In the Land of Drought (2015/2017), the viewer sees only aerial views for the entire 43 minutes of the film. ‘On screen, an army of scientists appears and investigates the remnants of civilisation after humanity’s self-extinction. Shot entirely using a drone, Rosefeldt’s images hover meditatively over the desolate landscape and ruins. Connoting surveillance, the drone’s bird’s-eye view removes human perspective with the viewer kept at a distance throughout,’ states the description of the work in the catalogue for the Riga International Biennial of Contemporary Art (ongoing through October 28).

A scene from the video work In the Land of Drought (2015/2017)

It seems to literally be ‘a view from above’, which is why, if one pulls in closer, this sort of approach to the material could be called religious even if Rosefeldt hasn’t mentioned any specific gods in his latest works. We are simply given the opportunity to look at everything through a god-like lens – from the same point of view of as that of the ‘higher being’ who is just as watchful of stray dogs roaming through the abandoned remains of a block-buster movie set somewhere in the Moroccan desert as it is of the geometrical layouts of abandoned factories in the Ruhr, Germany.

The successfully epic video-story In the Land of Drought can currently be seen in the large empty auditorium of the former Faculty of Biology, accompanied by a scrupulously crafted soundtrack (a balanced combination of noise and rhythm) created by Rosefeldt himself. As the work comes to a close, figures dressed in white lab coats and caps assemble inside of an amphitheatre which, from the ‘drone’s-eye point of view’, looks like a gigantic eye: ‘[…] a dialogue unfolds between the two perspectives of control: the eye on the ground and the drone's eye overhead […] the figures draw close only to disperse again. Reminiscent of cell division, […] hint at a prospective optimism amidst a dislocated world man has created.’

Also strangely optimistic is Rosefeldt’s first ‘real’ feature film – a joint project with Cate Blanchett which was originally shown (in Melbourne, in 2015) as an installation on 13 screens with a complexly timed dramaturgy, and which was later re-edited into a linear feature film in 2016. Titled Manifesto, it is a wonderful dialogue between human rhetoric (lines and whole pages taken from 20th-century art movement manifestos) and urban architecture filmed in and around Berlin. Berlin is also the city where Julian and Cate first met at an exhibition opening. However, in Manifesto, architecture is neither an illustration nor a corresponding backdrop in terms of tonality. In an interview for the film, Rosefeldt said: ‘Architecture [usually] underlines the narration or announces it. In my work, I do the opposite – I don’t use architecture to explain what happens, I mainly use it in an enigmatic way, so the architecture becomes an alienated place to the text that the action unfolds there.’ [sic]

A scene from the film Manifesto (2016)

The architecture here really does ‘alienate’ the strings of words. Yet the various characters played by Blanchett speak the texts not only in front of the buildings but also within them – at the dinner table in a bourgeois dining room, or in a modern-day classroom in front of nine- and ten-year-olds. In his early video works, which he began showing in art galleries in the mid-nineties, Rosefeldt often accented daily life, including media clichés and rituals. Here, though, he works with text – with a narrative – and shows us how it works when juxtaposed with a completely disparate setting; for example, schoolchildren in a classroom recite the tenets of the Dogme 95 Manifesto as if it were a multiplication or conjugate verb table.

It’s all a bit sad (i.e. while watching, I felt pity for some of the manifestos for having entered such unaccustomed situations), but also interesting. And it’s not illustratively beautiful like some of the surrealism collages of the 1920s and 30s, in which the overlapping of various realities looks like an amazingly accurate discovery of meaning. It just so happened that thanks to the Biennial, we had the chance to speak to the artist in Riga about both Manifesto and The Land of Drought, in the same building that used to be the Faculty of Biology. We sat down on a high and wide window sill on a stairwell landing situated between two floors. Rosefeldt spoke in a calm and confident voice, occasionally breaking into a timid smile above his three-day beard stubble.

A scene from the film Manifesto (2016)

When I finished school, the libraries that were accessible to me barely had any books on avant-garde or contemporary art. Yet I did find a wonderful collection of 20th-century cultural manifestos that had been published as educational material. That’s where I learned about the dadaists and the surrealists. I was also intrigued by the peculiar style of the text – it possessed a special kind of credibility and power. How did you come up with idea to work with bygone manifestos, and to give them the opportunity to ‘come back to life’ in your film?

I began rereading them while working on a completely different project. First of all, I was surprised at the unbelievable energy that was locked into them. An energy that aspired to break the ties to the past but which, at the same time, was more interested in the present than the future. And that is what really interests me – an outlook of the world that is deeply rooted in the sense of the present moment. On the other hand, I was captivated by the poetry of these texts – their lyrical quality. We now know many of the authors of these manifestos from their visual works, yet often the manifestos were written before the authors were able to execute their visual ideas. Now we perceive their statements as something solid and fundamental. But for me… yes, it is something fundamental but at the same time, very fragile, because in most cases these artists were very young when they addressed the world in written form. When you’re just a few years past twenty, you can be loud and angry yet, at the same time, you’re fragile and unsure – about what you want to achieve as well as about who you are. That’s why you’re angry and loud. You play in a punk rock group, you go to demonstrations… or, you write a manifesto, which is an expression of this very fragile and sensitive period in life.

And so I began to read these manifestos and think about which of them have not lost their meaning or can still be applied today – in our time, when it seems that manifestos have completely gone out of fashion. And that’s also interesting – but why is that? On one hand, we now have a huge global art world with an unbelievable number of artists and positions and diverse approaches, but back then, say, in 1909, when Marinetti was writing his manifesto, or in the early 1920s, when a whole other bunch of manifestos appeared, the people conceiving these ideas were just a small minority of the already small number of individuals who made up the artistic community. The vanishing of manifestos was also influenced by the fact that in today’s world, an artist can realise themselves in many different ways. Today we have an interview, tomorrow there will be a panel discussion, you can create your own blog in which you can publish your thoughts, or make your own website. All of that has come to replace manifestos – it’s made them unnecessary, antiquated.

Although I myself try to avoid the word ‘antiquated’ because I believe that we need manifestos more than ever before; I even think that we may soon experience a rebirth of expressing one’s positions in writing or verbally. Moreover, it is all happening on a backdrop in which populism is gaining strength, and where the main feature is that our world is being made simpler and dumber. Artists are angry and loud, but populists are also supposedly angry and loud. Yet they are just pure ‘noise’ – they’re selling only fear. Behind it all is a vacuum of ideas, whereas in artistic manifestos you’ll also find a great deal of anger, but the anger is tied to an unbelievably creative message, and with inspiration. What activates you as an audience is also what encourages you to concretise your ideas. These texts are very poetic and saturated with the energy of thought – they can serve as a great form of protection against the dull anger of populism.

A scene from the film Manifesto (2016)

I also see your film as a very interesting work on the theme of contextualising expression. Here, the words of the manifestos are placed in situations that make them more fragile or alienate them. There are similarities with the studies in which the way a text is perceived depending on where it is being said or by whom it is being said, e.g. a bum on the street, a teacher, a housewife, or a television newscaster.

As I said, I wanted to clarify how relevant these texts are in today’s world. That’s why I wanted to transfer them to this day and age also visually. Of course, I didn’t do it by using a direct analogy to the content of the manifestos. For the most part, I used settings that looked enigmatic and that didn’t correspond with the text. In commercial film messaging, and also in ‘normal’ art-house cinema, you’ll often see how the architecture is taken advantage of to emphasise the content, or how the music announces the emotions. I try to avoid that. I’m interested in the mysterious discrepancy between what you’re seeing and what you’re hearing. I create conditions that don’t emphasise the text, but rather activate you as the viewer. It’s a simple method that is rarely used in conventional film, but I wish to involve the viewer with what is happening on the screen in a different way.

Moreover, the context that is utilised in Manifesto reflects the so-called kaleidoscope of today’s society and its various layers and the social and professional groups therein. This is, of course, the Western world simply because the film’s lead character speaks English, but she uses thirteen different dialects that aren’t all that easy to pin-point even for English speakers. It could be Canada, Scotland or New Zealand. You’re never completely sure of where you are at any given moment.

A view of the 13-screen installation Manifesto at the Park Avenue Armory (New York, December 2016) © James Ewing Photography, Park Avenue Armory

It was originally an installation, which you then made into a film. Did you do any additional filming or add anything new to the film version?

For me and Cate, the installation was the main idea that we wanted to realise. In order to finance it, I met with people from the film and TV industries. They said they would help us, but only if we could offer them something in return. Cate and I pondered this and, at first, we couldn’t even imagine how it could be done. But then I convinced her that we could make a fantastic job of it – we could come up with a complementary linear version that would later be shown as a feature film, and would thereby also reach a completely different audience. And, at the same time, it would also work on a different level – just like many of my other works do – by doubting the messaging and perception models used in conventional film and which we take for granted when watching a film.

It’s interesting that in the more than one hundred years that the film industry has been in existence, the moving image has not abandoned its three framework formats: short, feature, and documentary. Even though the moving image inherently allows for so many things. That is one of the reasons why I don’t work with narrative film, but rather show my works in the context of contemporary art.

In the installation version, thirteen screens are in use; one of them is the introductory screen showing quotes from texts, starting with the same Communist Manifesto by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, which became the template for this genre and upon which many artists later oriented themselves upon. On the remaining twelve screens we see thirteen characters (one screen has two – a TV newscaster and a journalist having a discussion). Each screen shows a video that is ten and a half minutes long, on loop. In the film version, perhaps you noticed a moment at the very end in which the screen is divided into twelve cells with all of the characters speaking in the same tone and timbre, thereby creating a kind of choir. That is the key moment of the installation – this effect occurs once every ten and a half minutes. The twelve characters look you straight in the eye and speak in the same tone; this was, of course, specially edited to make it happen. It creates an effect of spatial harmony – the impression of a harmonic choir made up of many 20th-century opinions, united in one voice – the voice of art speaking to society.

We cut quite a bit of material out of the film version, and we were well aware that we were expected to produce a story/plot that would take the viewer by the hand and lead them through it. But we’re not presenting such a story here. We don’t even have twelve short stories – we have twelve situations, you could say. And we were well aware that we need a visual narrative in place of a verbal one. And that’s what we looked for. We don’t have a specific time-line, and the parts don’t closely follow one after the other in succession – we understood during the first sample edits that that would be very boring. Instead, they latch on to one another, they interact, and together with the film effects and the soundtrack, they nevertheless do create a peculiar kind of linearity.

For me, the strong side of the the linear film version (along with its provocative nature in the context of film industry norms) is its different level of textual concentration. Because here you hear only one voice; there is just one person telling you something. It allows one to read art history as a kind of unified line of thought. In the installation, you can choose between listening to the cacophony of the whole or just concentrate on a single one. You can do your own ‘editing’ by choosing how much time you will spend by each of the screens. You can look at them in any order of your choosing.

A scene from the film Manifesto (2016)

Architecture plays a large role in the film version. But how about in terms of the installation? The scenes are one and the same, aren’t they?

Yes, they are. But the film is 94 minutes long, including the credits; the installation version has 130 minutes of material.

It was shot in Berlin?

Yes, except for one building.

It seems that your architectural education helps you use scenes with buildings and structures as a true visual language.

My architectural education is probably very evident in what I do. I often use architecture as a theme or as the object in my work on screen. I even create my presentations based upon my conceptions of architecture.

In Manifesto we see Berlin and its surrounding area, but in the work being shown at the Riga Biennial we see desolate regions of Morocco and abandoned industrial sites in the Ruhr. I understand that in Morocco, filming took place in former film sets that had been built in the dessert at the end of the 1990.

They are also being built now.

A scene from the video work In the Land of Drought (2015/2017)

While watching, I was wondering how old they really are. Obviously, time is eating away at them as well.

It’s good that you immediately thought of the set decorations. Some people perceive them as reconstructions of historical buildings or restoration works. I got the idea to film them when I was in Morocco and learned of the city Ouarzazate – the centre of the local film industry. The landscape there is ideal for all ‘biblical’ films that feature ancient Egypt or Rome; Gladiator and Asterix and Obelix were filmed there. Lately, a lot of the films made there are set in Iraq or Afghanistan. The technical control in Morocco isn’t very strict, and often times once a film wraps up shooting, the crew leaves everything there as is and just leaves. All of the sets are left to the water and wind to do with as they wish, and they eventually disintegrate; I think that is amazingly beautiful. We also saw stray dogs there. Actually, the dogs you see in the film aren’t strays but ‘film animals’. That’s when I came up with the idea of showing them as the only inhabitants of this place.

This whole project came about on the initiative of the organisers of the Ruhr Biennial, who asked me to shoot video material for a two-hour concert featuring Haydn’s The Creation, performed with a choir and orchestra. I told them that I would gladly do it if, afterwards, I can use the material together with a completely different musical accompaniment specially created for it. And that’s what happened with In the Land of Drought.

[In the film,] we are looking at the world after a global catastrophe. Civilisation has made a grave mistake on a human scale, and has disappeared from the planet. All that’s left are all kinds of ruins. From the ruins of Mesopotamia and Ancient Egypt to the ruins of the industrial world. Those we filmed in the Ruhr, of course.

The idea is very simple – returning to the upcoming future from a very distant future. An army of scientists lands on Earth to find out what happened.

A scene from the video work In the Land of Drought (2015/2017)

They’ve come from another planet?

Or they could be the descendants of the survivors, who have been able to hold on and survive in some faraway place. I don’t want to explain it; I want to leave space for the viewer’s own fantasy. But my own thoughts are of an army of scientists who return to the past, which is still in our future. It’s like a return to the scene of the crime. Or a scientific expedition. That’s why I’m very happy that the curator, Katerina Gregos, has displayed the work here, in a place that is closely linked to science – an auditorium where the results of other studies have been presented for decades on end.

The audio accompaniment was made together with my friend, the sound designer Fabian Schmidt; we tried to imagine the music of the future, which isn’t all that similar to music but sounds sacral and has a ritualistic mood to it. This sound corresponds with the very powerful ritual performed by the visitors at the end of the video work. A kind of eye is formed, reflecting the ‘eye’ of the drone with which it was filmed. A vibration or pulsating takes place; the ritual reminds me of what cell division looks like under a microscope – the cornerstone of all life on Earth.

A scene from the video work In the Land of Drought (2015/2017)

I can’t get rid of the thought of these gigantic film sets in Morocco. They look like ancient historical complexes, but at the same time, they’re built of plastic, veneer and papier-mâché – modern materials that quickly break down. It’s like a metaphor for ‘fast history’, reminiscent of these numerous pseudo-theories purporting that history is really much shorter than we’ve been taught – that Ancient Rome existed just two or three hundred years ago, and so on.

Yes, that’s an interesting parallel one can draw.

I wanted to ask something else: In your works, you frequently take a close look at routine, the daily ritual of existence. Right now, you’re a guest of the Riga Biennial, and these sorts of events are also have their own kind of rituals or clichés, as does the art world in general. We all understand what an ‘exhibition opening’ or ‘award presentation’ is (including what an ‘interview with the artist’ is). How do you feel in these sorts of situations, when you participate in them but are completely conscious of their partly ceremonial character?

There’s a whole spectrum of possible answers to this question. Of course, if you’ve chosen to go down the road of art, it may be that you may expect a bit fewer rituals than if you were a clerk in a bank or some other office worker. And yet artists also become caught up in a slew of these kinds of traps. My interest in these sorts of things appears as soon as I comprehend that they are also happening to me: ‘Stop! What am I doing?’

I see life as a complex and absurd system that occasionally is also very interesting. I’ve devoted whole work cycles to this theme. It can be partly noticed in my work here at the Biennial as well as in Manifesto. Of course, as an artist you inevitably become a participant in the rituals of the art world, which locks your ideas into circulation just within the very narrow boundaries of ‘“white cube’ exhibition space status”. And that’s why our art doesn’t reach the audience that it should, and instead, our exhibitions draw friends and admirers who don’t need to be convinced of anything. They already share our views. In this sense, It seems to me that the Riga Biennial is realising a completely different model by using buildings and spaces that are very far removed from the ‘white cube’ model, and bringing together into one dialogue works that have been brought in from a variety of countries with their own local art and local audience. I think we need more events like this in which we, as artists, don’t feel captured by the traps of the art world.

A scene from the three-screen installation Soundmaker (2004)

In your 2004 work Soundmaker, the camera rises vertically upwards, revealing to us the illusionary effect of what just took place. Was that the first time that you used this technique?

Let me think… It probably was, even though I had already deconstructed the ‘behind the scenes’ of character creation in all sorts of ways. Nevertheless, this episode really is critically important in terms of what I do and what I’m trying to get across. It shows the truth as something construed, created with the aid of rituals. And as the camera rises higher, you see everyone who was involved in the filming process, in the creation of this chain of characters; you also see me, and the camera man… This moment demonstrates the whole microcosm that was necessary for us to see what we just saw. I’m very interested in the idea of a reality that is an artistic notion, or a notion that becomes reality. That corresponds exactly with my belief that everything that we create is a kind of echo of what we have read, seen, consumed, heard. There’s nothing absolutely original; everything that we give of ourselves is a reinterpretation or reworking of something that has already been.

A scene from the film Manifesto (2016)

In Manifesto, Cate Blanchett intones in a classroom: ‘Nothing is original...’

‘...Steal from anywhere.’ Yes, that’s one of Jim Jarmusch’s golden rules of filmmaking.

But then she concludes by saying: 'It's not where you take things from...’

‘..It's where you take them to.’ I would also underline every word here.

This makes me, once again, think about the view from above, from a distance – which is used often enough in the film world, yet here it is used with a completely different objective – and also about filming with a drone, which are being used so much now. Was the first scene of Manifesto also filmed with a drone?

Yes, exactly. On an unconscious level, it gives you the idea of an almost scientific perspective on human existence. Halfway scientific, objective, or at least attempting to be so…

And halfway religious?

Halfway religious. Or pseudo-religious. I am not a religious person myself. However, there is a way to look at human existence in a much broader context, and it can be generated thanks to this perspective of the drone. And that’s what I find interesting.

Julian Rosefeldt at the former Faculty of Biology building in Riga. Photo: Kristīne Madjare