There’s constant background noise

A conversation with Paulis Liepa, artist and nominee for the 2019 Purvītis Prize

04/03/2019

The Cabinet of Fine Arts, the title of a series of artworks by Paulis Liepa, is misleading. Or, more precisely, it’s only partially true – images of graphs, diagrams, and curved lines are not exactly the first things that come to mind when one hears the words ‘fine arts’. Even if they have been carefully framed, glazed with coloured varnishes, and placed behind glass. Adding fuel to this ‘fine’ fire is the information being presented by the graphs and curves – it turns out that many of them were created by analysing data on weapons and their use in various parts of the world. Bullet trajectories, the cross hairs of a gunsight, and a cross-section of a pistol are just a few of the first elements one recognises. Liepa does not completely explain all of the content that we see, emphasising that the image is meant to elicit distance and mystery, as well as leave space for the imagination. In his view, we are too distanced from the whole military conglomerate nowadays – we are thoroughly alienated from the physical suffering and raging emotions associated therewith. In our conversation, Liepa compared it to the ballet – an art form that looks completely different than what is actually happening inside of it.

Paulis Liepa (1978) has consistently worked with graphic arts techniques – from the seemingly simplest forms of collagraphy and cardboard block printing to letterpress and silkscreen printing. Long-standing subjects of his have been daily life and its associated memories. Spatial layouts and technical drawings of objects encouraged him to reflect on geopolitical changes that have occurred in the last half century. Since 2004, Paulis Liepa has had thirteen solo shows. For his exhibition Klusā daba (Still Life), he received the Diena newspaper’s Annual Culture Award for 2013. In 2005 Liepa received his first award of recognition at the Graphic Art Biennial of the Baltic Sea Countries ‘Kaliningrad-Königsberg’, but by 2008, he was the Grand Prix winner at the same event. In 2018 he participated in the 1st Riga International Biennial of Contemporary Art. The exhibition The Cabinet of Fine Arts, for which he is now nominated for the Purvītis Prize, was held at The Mūkusala Art Salon in 2017.

The Cabinet of Fine Arts exhibition view. Publicity photo

Are you still a big fan of football? What are you focusing on right now about the game?

The fact that the World Cup is dying out. One could say that, as an event, it’s been destroyed: for instance, the next World Cup will be held in the winter, in Qatar, and it will end shortly before Christmas; the number of teams participating in the following World Cup will be 48 [an increase from the current number of 32 – Ed.] It’s becoming a joke. Of course, these are only problems in the eyes of football nerds – the games will continue to be played, and I’ll surely be watching anyways.

You seem to be quite invested in it...

Yes. It’s a four-year process that is being increasingly commercialised. They’re selling more broadcasting rights, more advertising, more everything. The spirit of the event is being ground into the dirt. I could talk about this all night. For example, there are 32 teams – that’s eight groups with four teams each… Have you ever watched?

No. That’s why I’m listening with such interest.

Every group has four teams, and a total of six matches are played within a group. Each team that has gotten that far knows that they will play three matches. This creates a bit of drama already. In their first game, the players sniff things out; in the second, they become serious about the whole thing; and by the third match, it’s defining – will they go further or not? If there are 48 teams, that means there will be three teams in each group. That messes up the whole scheme. I could talk for hours on why this is bad...and only bad – there’s nothing good about it. The whole symphony of life falls apart into pieces. But that’s going to happen eight years from now, and there’s still the European Championship before then. They’re simply these monumental events for which people schedule vacation time off of work, buy new TVs...at least it used to be that way. Guys would go out to the countryside and just watch football. It is a form of addiction, actually.

We have yet to see football in your art.

It is there, but it’s secret. All sorts of numbers and names creep in. I haven’t dedicated any works or exhibitions to it. The pictures contain daily noise, which is often rooted in football. I really can’t do it any other way since I’m watching football as I cut up the cardboard.

So, football is on in the background when you work?

Usually. I probably listen more than watch. For instance, if the World Cup is on, but I have a show in two weeks, then there’s a conflict – which one takes the upper hand?

Do you miss any goals?

No, I miss out on the important things, like watching the glue dry.

The Cabinet of Fine Arts exhibition view. Publicity photo

Thematically, The Cabinet of Fine Arts, for which you’ve been shortlisted for the Purvītis Prize, is not typical of your work: it used to feature more design- and daily-life-based motifs. Aren’t you a bit disappointed that this side of yours won’t be seen in the exhibition featuring the finalists for the Purvītis Prize?

No; this direction, or a similar aesthetic, has been simmering in my mind for a while now. Ideas take a while to come together to the point where you can execute them. At first, there’s just a vision; now, its a new offshoot. What came before hasn’t disappeared. I don’t feel as if my previous work hasn’t been sufficiently recognised.

You don’t feel as if you’ve gone off your subject?

An artist can’t veer off course. If he does something, it’s like his diary. It’s impossible to mechanically make something from nothing. What has been made doesn’t go away.

N20317R, 2017. Plywood, paper, mixed media, 33 x 33 cm. Publicity photo

The Cabinet of Fine Arts was altogether war themed. Are you interested in that?

Overall, it’s difficult to draw a contour around that exhibition. The subject is the quest for truth, or the hiding of it, in both cross-sections and the rises and falls of curved lines. There appears a struggle for spheres of influence, control over geographical units, and cold, cynical calculation. Humanity is like an infinitely complex mechanism with friction, tension, material fatigue, and steam that needs to be released. Mutual agitation occurs and, unfortunately, war is an integral part of human existence.

Graphs and schematics are the ultimate trivialisation of numbers – the sequential layering of a cheese sandwich and the colouring-in of war machines – until everything begins to resemble a children’s game: a virtual phenomenon that lives only on the radio and in history books, but in no way affects us in the here and now. In short, schematics and concepts are twisted up with each other so that everything impedes everything else...and no one is in charge.

Nowadays, people have the power and ability to calculate things and to work by following previously proven formulas – ‘hybrid war’, for instance. Luckily, a lot of the fighting is done over the internet. Conflict and collision are inevitable in any dimension of our existence. Friction, interaction, and the energy that breaks out in an unexpected moment...of the kind that results from the movement of tectonic plates. In terms of tension, the point of critical mass is attained, even if the whole thing had been made from rubber.

How do you learn about this? Do you read a lot of news and history books? Do you visit military antique markets? Those are a whole subculture in themselves, are they not?

Yes, there’s football and other things that people do in the same, almost religious, way. Regarding history books, no, I would love to know history better. But it is quite difficult to live without being affected by everyday background noise. For example, I remember when Barack Obama was first elected. Or the Trump and Hillary affair. For a whole year I was surrounded by CNN, percentages, bar graphs, tweets, and what not. It is yet another branch of humanity's common existence which cannot simply be cut off, sawed off and forgotten. And, of course, all of the can’t-miss events regarding Ukraine. The most painful moments took place in 2014, 2015...now we no longer hear about it, but it’s still pulsating in the background. That’s when I got the feeling that there is some kind of parallel intelligence...calculations...that there is an underwater fight going on all of the time.

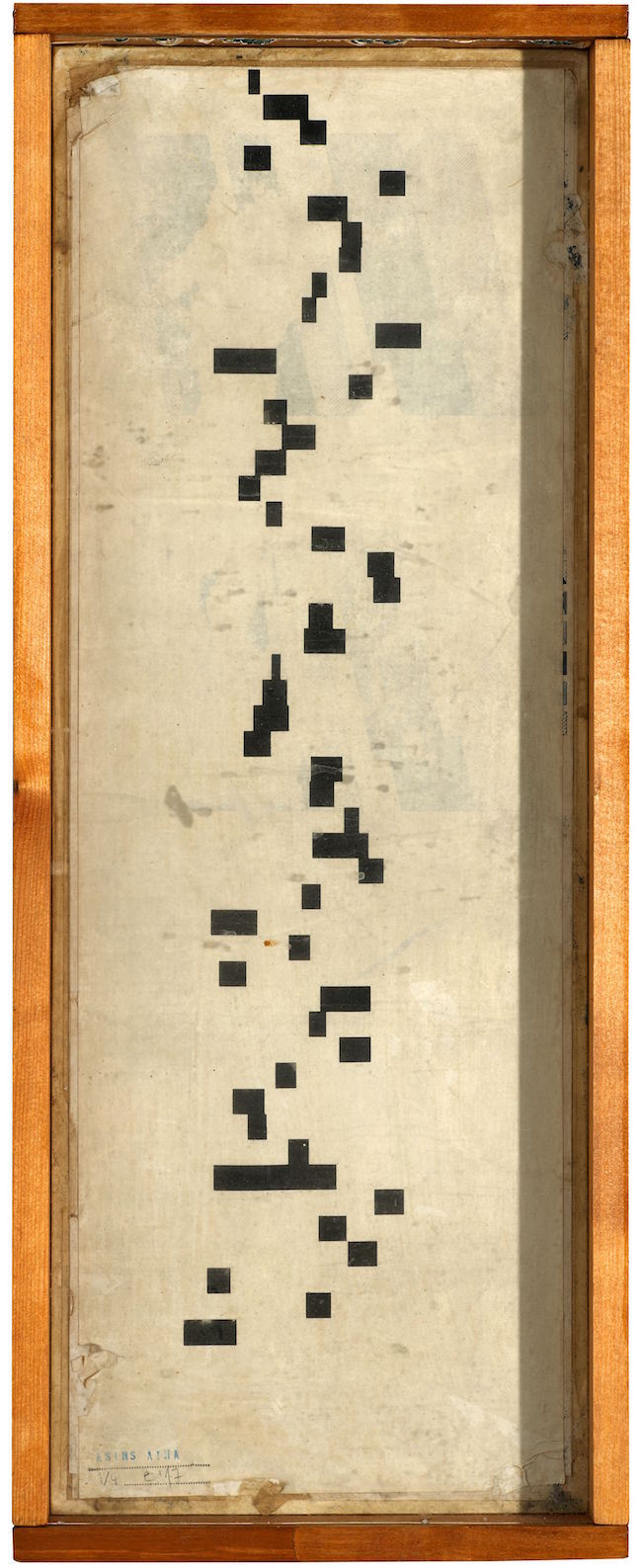

Blood count, 2017. Plywood on paper on cardboard, 63 x 23 cm. Publicity photo

I like how you speak about this in a removed way, through the language of schematics and graphs. Is that because we really don’t have much influence on these things?

Yes, that too. But what is it that we call war? When things explode and bullets whistle by. But it’s a whole industry in which everything is aestheticised and presented to people by way of live broadcasts, reporters from the front lines, and so on. Everything turns into percentage bar graphs – there are no dead bodies, but there are infographics. Pretty lines and numbers. It may sound ridiculous, but the war industry is the same old physics and chemistry. It can all be expressed through numbers. Behind the scenes there are curved lines, trajectories. Serious people – scientists – work at coming up with ways to damage the opponent's side even more. For instance, how can we blow off more legs. This is done with protractors, French curves, and formulas in a removed setting. Some guy makes up the technical drafts and then disappears behind the door – as if it what happens next doesn’t concern him in the least.

War photojournalists present us with disturbing close-up pictures of mangled and burned flesh. Usually, when art latches onto similar themes, it highlights these ‘expressive’ aspects.

It think the mathematical aspect is much more cynical – precisely because of its incompatibility. The algorithms and the drafting table translate as the other half of the equation. That is the other side of war – the family man/woman who comes home every day after working at the office.

Did you make any shocking discoveries while working on this project?

The works are much more abstract; they don’t contain much tangible information. It has always been important for me when making, for example, a picture of a room with a book shelf, that the books’ spines are arranged according to a string of numbers. They’re not set up randomly with their differing heights.

Strings of numbers? Where do you get them?

It depends. I’ve used football scores. One time, the end result looked like abstract graphic lines, but I had taken ten games and the minutes during which the goals were scored. For example, at the third minute, the eighth minute, and so on. It looks kind of like a barcode. But I’m just talking about this now – the ‘formula’ itself doesn’t appear in the images; I don’t write it down in the corner of the picture. When translating it all into visual signs, I don’t have random lines – they draw themselves. I think it always turns out better and more beautiful than if I were being guided by any artistic feel for it.

Are you pedantic? Do you tend to rationalise everything?

Perhaps. I’m a workaholic. In my art, I like to put life into play. The exhibition we’re speaking about had graphs, curved lines, slopes...at the basis of everything are number series. In one piece, there’s the ration of men to women in the human population – it’s microscopic, 101 to 100. You can’t even see it. There was one thing which I thought was well known, but I had great difficulty finding it: how the population of the Roman Empire grew and then shrunk. It’s depicted in a graph.

N21317R, 2017. Plywood, paper, mixed media, 33 x 33 cm. Publicity photo

Don’t you explain this in the work’s accompanying text?

No; I like encrypted messages. History geeks might detect it; it’s along the lines of the golden ratio or Fibonacci numbers.

You say you’re a workaholic, but at the Māksla XO gallery, I heard that you work slowly.

Let’s not get hasty. First of all, the graphic arts are a technical event – it takes weeks to crystallise, for a real cliché to be born. The problem is that, for me, the intensity of it all grows exponentially as crystallisethe deadline approaches. Only then can I settle into the right pace. It is not possible to work towards an abstract future – to finish a work today that will be needed only two months from now. It’s not possible for me to make any responsible decisions...I can't decide between red and orange-red today if I don't need it by tomorrow. My brain will not feel the necessary intensity.

Preparing all of the glues and cardboard also takes time.

Do you still consider yourself a graphic artist? You also uses painterly effects, varnishes and so on…

The exhibition in question involved a lot of silkscreen and letterpress printing. I like the mechanical part of the graphic arts. The image is produced without using your hand; there is no brush stroke. Printing creates a gap between the artist and his work, although the artist has, of course, worked hard to get all of the details just right. However, the surface is produced by technical means, which gives the work the impression of being a document.

Do you still make just one copy of each work?

No! In fact, there have always been two or three. There are only a few of which there is just one copy. Only the ones with adhesive layers cannot be reproduced. There are also some works that have the character of a painting or an object. Of course, if the work has been lacquered and framed, then one has to ask what the second copy of a print run of two will look like? Mechanical means should then also be used to make it the same as the first. There’s something I like about this whole thing.

Paulis Liepa. Publicity photo