Neo-baroque around us

Conversation in St Petersburg with members of the Russian art group AES+F

12/08/2019

Predictions and Revelations at the St Petersburg Manezh Exhibition Hall is a show featuring five large-scale videos, prints, sculptures, as well as a mobile application from MTS and plasma panels in the façade intercolumniation of the building, informing every passer-by 24/7 about the AES+F exhibition open though late September.

AES+F. Islamic Project. 1996.

The group of artists, founded in 1987 by architects Tatiana Arzamasova, Lev Evzovich and Evgeny Svyatsky (later, in 1995, they were joined by photographer Vladimir Fridkes), alongside Timur Novikov’s New Academy of Fine Arts, was one of the first in contemporary Russian art to re-examine the concept of beauty, doing it with different means ‒ actively using methods of mass media and pop culture. After their Islamic Project, which was launched in 1996 and gained new relevance in the aftermath of 9/11, the artists were so often declared ‘prophets’ that the members of the group eventually grew accustomed to their oracular role ‒ or at least they cannot afford to disregard it completely now. The Liminal Space Trilogy, created in three stages and comprised of video installations Last Riot (2005‒2007), The Feast of Trimalchio (2009‒2010) and Allegoria Sacra (2011‒2012) with their perfect visual form, allegorically describes the beautiful yet simultaneously terrible future towards which the human race is moving with doomed inevitability. The same parable style and universality is fully revealed in the Inverso Mundus project dating from 2015‒2017 and inspired by images of an ‘inside-out world’.

During the vernissage days, the artists are almost constantly busy with interviews, guided tours, the photographing and video-recording of the mounted exhibition. Our conversation at the Manezh café starts with Tatiana Arzamasova, who is brought the coffee she has ordered. ‘I’m so happy,’ she says, ‘I’ve finally figured it out that espresso is strength-wise like americano here, while ristretto is actually espresso.’ Evgeny Svyatsky joins us to answer some questions, Vladimir Fridkes also lingers for a short while, but Lev Evzovich does not show up at all. The whole conversation takes place to the sounds of Turandot coming from the second floor: the scenic design of the opera, a production that opened at Teatro Massimo in Palermo in January 2019, is the most recent work of AES+F to date.

.%20%D0%A4%D0%BE%D1%82%D0%BE%20%D0%9C%D0%B8%D1%85%D0%B0%D0%B8%D0%BB%20%D0%92%D0%B8%D0%BB%D1%8C%D1%87%D1%83%D0%BA%202.jpg)

AES+F (Tatiana Arzamasova, Lev Evzovich, Evgeny Svyatsky, Vladimir Fridkes). Photo by Mikhail Vilchuk

The length of the video works shown here at the Manezh range from forty minutes (Inverso Mundo) to over two hours (the Turandot opera). In what way should the viewer interact with them?

Tatiana Arzamasova: It is absolutely not required to be prepared for viewing our works. Sometimes we receive completely unexpected transcripts and totally magical expressions of appreciation both from professionally immersed viewers and completely fresh people ‘from the street’. A contemporary person, not necessarily possessing any special knowledge and profound cultural background, may view one of our things in a nap-of-the-earth flight, as it were. Whereas for a prepared and visually educated viewer it is, of course, a deep mine: how deep he or she will penetrate it, depends on how far their oxygen level, brain and cultural background will take them; how many layers they will recognise ‒ that’s their business. We never imagine ourselves smarter than our viewer.

At the vernissage, a few people commented that the recognisability of actors famous for their roles in Russian TV series had been a hindrance to connecting with the videos; it had made it difficult to dissolve in the works and reach a universal level...

Т.А.: You can look at it through the eyes of a Frenchman or an Australian: for instance, someone from Sydney is more likely to recognise a local elderly lady, the collector Penelope Seidler, who appeared in Inverso Mundus than Svetlana Svetlichnaya, with whom we had the great pleasure to work on one occasion, in The Feast of Trimalchio. Andrey Rudensky took part in a number of our projects; he is the perfect character, we used him as ‘simply a man’. Danila Polyakov, a talented performance artist, the most wonderful freak in the world ‒ Jesus, centaur and Van Gogh in one...

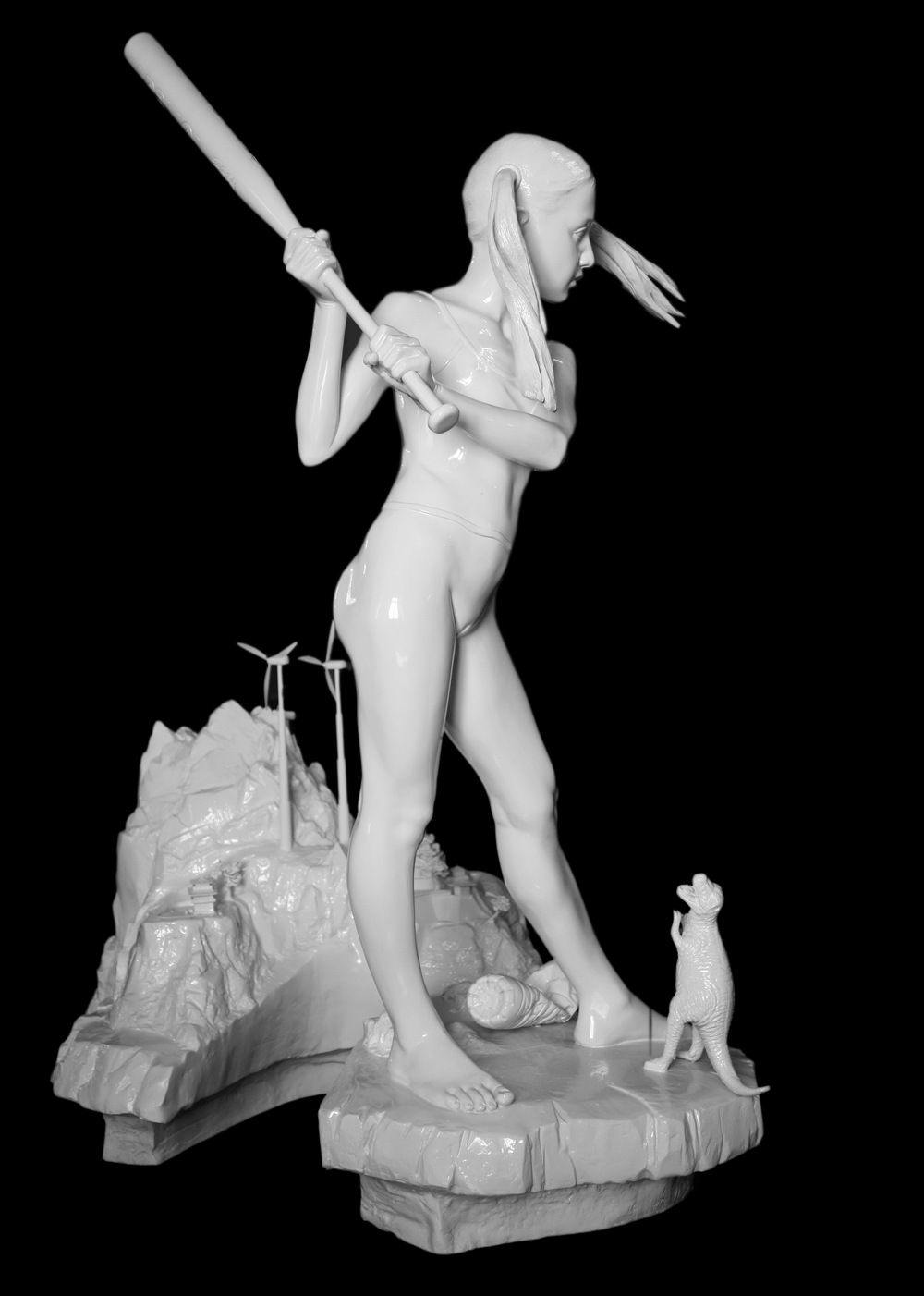

AES+F. Last Riot. Girl with a Bat. Composition #2. 2007. Cast, aluminium, enamel.

The artistic language of AES+F combines the visual approach of the 17th century with 21st-century technique. Baroque was made relevant again in the 1990s by post-modernism. In your opinion, is the baroque period still going on or has the time come for rococo now?

Evgeny Svyatsky: I strongly believe that art is not divided into separate unrelated periods; rather, it is like a river, its stream still containing within itself all the little brooks that have joined it, and they are easy to trace. You must have noticed how the laws of composition discovered during the Renaissance era or even images of totalitarian aesthetics are present in the contemporary iconography, in advertising or cinema: everything is still alive and applied in new ways, in keeping with the demands of the present day. Is the thing that we see now all around us ‘neo-baroque’? The way we see and feel it ‒ yes, indeed it is. The trademark feature of baroque is excess; it is expressed in the obvious dominance of the visual aspect. All sorts of expression are still going on ‒ corporeal, compositional. I believe that these stylistics have not as yet materialised as rococo, and the large baroque forms are still very much here. According to our professor of art history at the institute, rococo is a ‘boneless baroque’; well, so far the bones have still been present.

AES + F. Action Half-Life. Photo: Ruslan Iskhakov

The art of AES+F has been developing in keeping with the logics of progress, where each project is realised more perfectly than the previous one. What is the next technical record that you are planning to break? Perhaps it is the interactive aspect of the artwork that appeals to you?

E.S. We try to master the new media ‒ we already made a project in VR, Psychosis, which is on view at the Mars Centre for Contemporary Art in Moscow, and currently it is being presented as part of a special segment at the Rencontres d’Arles festival of photography. Is is obvious that any new means of expression will become part of the artists’ arsenal as soon as they familiarise themselves with it or, in other words, move on from being surprised by the actual technology to mastering its artistic potential.

Interactivity is appealing. Perhaps something like that will eventually appear in our work but it is difficult to name the project or time as yet. We take a very relaxed approach to various interpretations of the things that we do, understanding perfectly that a work of art starts to live a life of its own as soon as you release it into the world. And since that is inevitable, the next step of potential interaction is also logical ‒ that is, giving the green light to feedback. But that calls for certain inventiveness, the need to direct and anticipate in some interesting way the behaviour of the viewer, incorporating its variability into the actual idea of the work. I think that even in this case we would still remain true to ourselves.

Т.А.: A new project is obviously already present in our minds; it is based on a story dating from the pre-Christian times, one that almost any school kid is familiar with. We would very much want to place every viewer inside this story, make him a participant and let this world pass through his eyes ‒ if we can get it done. It is quite a complicated and tricky task, a genuinely very interesting one ‒ and the actual material is very good.

Feast of Trimalchio. Arrival of the Golden Boat. 2010. Digital collage, LightJet print

All of your projects have been made over the course of several years. What are the changes that take place from the beginning until the end, from the initial idea to the moment when decisions are already imposed by technology?

E.S.: Something always happens. We usually don’t make strict story boards, referring to a mood board instead; it helps us keep inside the associative field of certain ideas and merely adjust allusions and images that are born during the development stage. Improvisation often takes place during the shooting: new ideas, new combinations, new movements occur on the set when we already see the actors ready and wearing costumes. We don’t shoot frames; the frame appears and takes its place during the post-production stage, and therefore, once certain blocks and episodes have been lined up, it sometimes seems a good idea to change their places.

Т.А.: However, the general idea of what we want to create is always present, floating like a flying saucer above us; it does not go anywhere.

Fragment of exhibition at the Manezh. Photo by Mikhail Vilchuk

Could AES+F repeat the artistic destiny of certain famous Western artists, like Julian Schnabel and Sam Taylor-Wood, and start making mainstream narrative films?

E.S.: I would never say never ‒ who knows? But it seems to me that we already are a bit over this idea. In the late 1990s, we really wanted to make a film and spent quite a lot of energy and time attempting it. Between 1997 and 1999 we wrote a screenplay with the poet Alexei Parshchikov; we even registered it in Hollywood. Funnily enough, the screenplay was born from a proposal by Nina Zaretskaya (TV Gallery) to make a documentary about us; we turned the idea upside down and decided to make a fiction film. We didn’t get as far as making it real, and perhaps it was for the best. The whole thing got somehow sublimated and incorporated into various projects ten or so years later.

Neither King of the Forest nor Suspects ‒ well-known works that have not lost their topicality ‒ have been included in this exhibition. Why? Was it because the subject matters were absorbed by the following projects?

E.S..: This was not intended by the curator as a formal retrospective, like the one that was mounted in St Petersburg, 12 years ago. This time around, it is more like a solo show, a large exhibition. The projects selected for it were the ones where the phenomenon of Predictions and Revelations was revealed most of all. King of the Forest exists in its own right, although there was this element of image anticipation: in the aftermath of the tragic events in Beslan, people wrote on the Internet that photographs of children in white rushing around were reminiscent of images from our project. It was a case of simple visual coincidence, but everybody said: they guessed it again; it was purely formal, rooted in a desire to find external similarities.

(Sounds of the finale of Turandot.)

Т.А.: This always sounds to me like a quote from God Save the Tsar.

In the Manege. Photo: Ruslan Iskhakov

What is your historical ideal? And what is the ideal form of government for you, if there is one?

Т.А.: I don’t find a single separate ideal in the history of art. It is this whole ‘tureen of soup’ as a whole that I find interesting. Sometimes I feel like telling about something by remembering a beautiful Pompeian fresco, sometimes ‒ by thinking about Rothko’s abstractions. You can find the anthropocentric element in everything. For this reason, I cannot single out a favourite period in culture for myself.

Speaking of a political ideal ‒ perhaps this will sound a little paradoxical, but there is a tiny state located in the middle of a very ancient city, and it unites people living in different continents. Vatican excellently functions as a state occupying a small territory with a park, a cathedral and a few buildings for its, what, 1400 or so residents. Over a long period of time, this state has not undergone any change at all, but it is admitting its mistakes and, strangely enough, trying to evolve as much as it can. I think this is quite an interesting form of government.

E.S.: Well, that’s very close to constitutional monarchy. I am a supporter of a democratic system and a republic. I think that a kind of electoral qualification does make sense, because one vote is not necessarily equal to another, and there are reasons for which people should have reached certain maturity. However, it is imperative that the views of every member of the society be considered and the views of even the tiniest minorities be listened to. Nobody should feel disregarded, disappointed, abandoned or robbed of their rights to equal opportunities.

Fragments of the exhibition in the Manege. Photo: Mikhail Vilchuk

Can your works serve as an ideal for people?

Т.А.: We have never had seen it as our goal. We are all ‘born in the USSR’ and we remember the ideological burden that art carried back then perfectly well. We always tried to softly evade the Soviet control, and that is why we are very sensitive regarding the attempts of censorship that emerge today. Who could suddenly start censoring culture and from what position? We are ourselves the first viewers of our works and we first and foremost think about avoiding didacticism.

The Russian consciousness by its nature is a narrative one; it is only afterwards that imagination develops in the visual realm. The narrativity happens individually in the mind of each viewer with his cultural luggage, associations and all that stuff; we have simply learnt to operate with a technique of imitating it. We value the cultural kissel or cultural protoplasm from which the viewer builds his own personal narrative. The way he understands the moving and shifting play of light and colour, the lifelike appearance of certain situations, stories or characters ‒ all of that is inside his head. We don’t want to exert any kind of pressure; we take care of a certain ‘technical support’, shall we say, but the rest is done by the viewer himself.

AES + F. Inverso Mundus. Shelving # 1–4. 2015–2017. Digital collage printing LightJet

Can your works be viewed in tracking mode or is complete meditative immersion necessary after all?

Vladimir Fridkes: I believe that meditative immersion is necessary. Moreover, I think that our works are built in such a way that, if you watch attentively and relax, they actually take you to such a state. I was forced to rewatch Inverso Mundo for a number of times: I had to show it in Venice to various people and my colleagues had all left, and I repeatedly caught myself losing track of time: I didn’t notice how the time passed ‒ what happened to these 40 minutes? There is this state of watching, and it is necessary. Afterwards, I hope, the viewer is left with some sort of impression and certain food for thought.

How do real and symbolic economy relate in your art?

Т.А.: There is no limit to consuming finances, and any of our works could easily consume even more. Nevertheless, we can make it possible for people to watch our work completely free of charge; for instance, here, on the façade of the Manezh building, fragments of our works are demonstrated to the whole city.

E.S.: The Turandot opera was staged in association with the Lakhta Centre company from St Petersburg; they wanted to support one of our new projects. Our proposal was to contribute to this opera production, and so they became the fourth partner on this project. The production is travelling through Europe, moving from one theatre to the next; next year will see it run in the third theatre, at the Badisches Staatstheater Karlsruhe in Germany. If everything goes as planned, we hope to show a video installation of Turandot in St Petersburg in January 2020.

Т.А.: The young director Fabio Cherstich from Milan and the artistic director of Teatro Massimo Oscar Pizzo invite non-theatrical artists to take part in their productions: Bill Viola, William Kentridge, AES+F. It was very comfortable to work with him; the director was very considerate; sometimes he even enhanced our visual image with his directorial decisions. The octogenarian maestro Gabriele Ferro became a true fan of our visual solutions. Turandot is a mixture of various cultures: a Persian legend with some added Chinese colour, retold by Gozzi for Italian theatre ‒ that’s the story to which we suggested adding the element of future.

Turandot. Jellyfish. 2019. Single channel freeze frame.

After Turandot, have you now found a taste for opera productions? Which opera would you like to stage next?

Т.А.: Our friend, artist Katya Bochavar from Moscow, has written a fantastic libretto (it is a secret for the time being). It is based on ancient Chinese and Korean stories about dreams. So we spent some more time brainstorming, and the result is a transhistorical tale: dream permeates the whole culture. Someone falls asleep, finds himself in the future and then wakes up again in the baroque Asia. What we need now is a new composer. Economic issues are always a matter of initiation. You just have to start, and the actual culture of opera helps bring it to fruition. Opera is alive. People will always find it interesting to watch these animals with the huge voices on the stage.