Having serious fun

An interview with artist Miet Warlop

07/11/2019

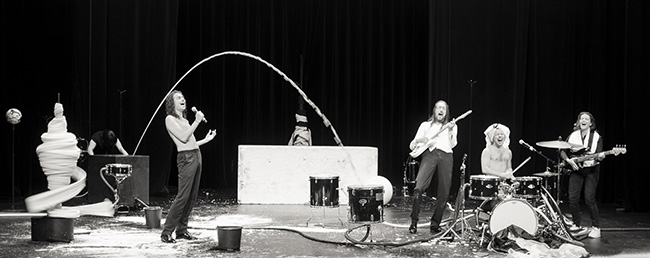

As she herself points out in this interview, Miet Warlop's (1978) work is difficult to classify into a particular genre. Performance artist, theatre director, scenographer, actress – none of these attempts to label Warlop are wrong in themselves, yet they all miss the bullseye. In her work, she gives primacy to an idea of something that must be shown and told instead of the form it's going to take, which, in turn, develops organically by way of any means of expression necessary. The Flemish artist graduated from the KASK School of Arts in Ghent and has created dozens of shows, performances, exhibitions and scenography projects which tend to overlap. She often takes these works on international tours; she first visited Latvia in 2012 with the show-painting Springville. To this year's Homo Novus theatre festival in Latvia, Warlop brought two performances: Fruits of Labor (shown twice) and Ghost Writer and the Broken Hand Break (shown once). Presented on the premises of “Rīgas kinostudija”, Fruits of Labor was a tumultuous, lively and loud concert-mystery with a strong emphasis on percussion and an overdose of various symbolic images that, with the help of lyrics written by Warlop herself, led the audience on a tour of existential journeys, occasionally surprising them, splashing them, or making them laugh. The performance was shown two nights in a row, and in the morning before the second one, I managed to meet Warlop for a chat. As it turned out, the timing was rather precarious because during the first showing of the physically demanding production, one of the musicians had broken a finger and Warlop had strained her back. Yet according to what I would later hear, those were deemed to be minor obstacles, and Fruits of Labor was successfully shown for the second time as well.

From performance "Fruits of Labor" © Reinout Hiel

Arterritory: Much to my surprise, a large portion of the audience was laughing a lot. Was Fruits of Labor supposed to be funny?

Miet Warlop: I don't think so. It was supposed to breathe and to show things in a relaxed way. Maybe that's what makes it funny. It's hard for us to hear the public while we are on stage. It seemed to me that in the beginning, the audience was silent, but then they kind of began to open up because they started to understand us.

Being the sole author and the director of the show, do you think you can answer for every bit of visual imagery and every symbolic element that was used? Or where some of them just random?

I think I can do that.

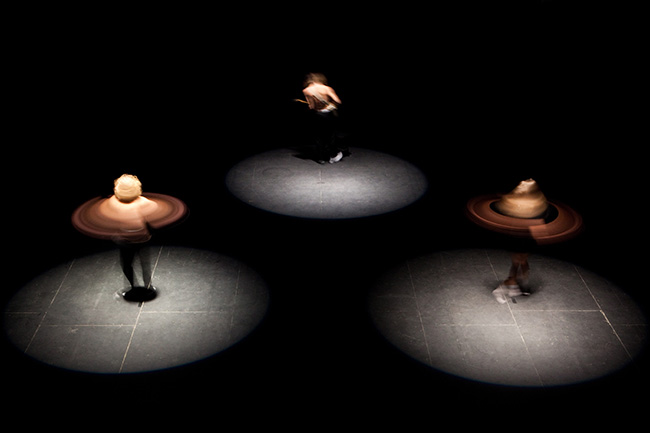

For instance, I was intrigued by the regular use of the whirlpool-like meditation technique that is often associated with Sufism. What purpose did it serve in the show?

One of the purposes this “whirlpooling” serves is looking for extasis, and I use it in many of my works. But in this show I use it not only as a ritual but also as a symbol for something else. This movement draws a certain sign – a circle, a circular shape, a movement with cosmic meaning. Lately, you can find it in all of my works. I am trying to reach a kind of extasis by dealing with all of the elements at the same time. For me, it symbolises the whirlpool of the Universe and helps me understand life. Religions and other systems of thought have done so much by shifting and transforming ideas and meanings... And so we ask – where are we now, what are the results of all of the things that have already happened? What are the results of all of this work that's been done before us? Hence the title – Fruits of Labor.

From performance "Fruits of Labor" © Bart Vermaercke

In the show and its texts, there's a lot of talk about “moving beyond language”. Have you managed to get there?

I think so, yes. I find it interesting, for I don't think that the reality described by language is the only one.

Can you describe what you do to make it happen?

To describe that, I have to use language, right? That isn't all that easy, you know. I can try to lead you down that path. Remember the scene where we use the white cube as a bull in the toreador show? As theatre, it's something very bad and banal, but we do it because we're not interested in technical and academic quality. It's not about the quality of the scene or the story of the toreador; in this way we are trying to lean over not only language, but even the image. Not only in this scene, but others as well, where we are trying to refer to religion, terrorism, traditions, this thing with a psychotic Jesus and the crucifixion... By showing all these things together, though not in the way that it's usually done – without thinking about the style and quality – I think we do, in a way, “go beyond”. We go beyond the need to talk about all of these things like quality, form, beauty... All of these conventional, conservative things are put aside, and I think that that which remains is much more interesting.

From performance "Fruits of Labor" © Laurent Philippe

What were the states of mind in which you wrote those lyrics?

You mean, was I drunk enough? (Laughs.)

No, not exactly. Rather – have you noticed the patterns, the situations in which they come to you?

Some of the texts I wrote a long time before Fruits of Labor. But for me, the reason why it happens to me is, I guess, what characterises human existence as such – embarrassment and fear. Am I healthy in my head, you know? Is the way I am how it’s supposed to be? There are all these things, religion and your beliefs, all of the attitudes among which you have to find your own way... So, the moments when I write these texts are the ones in which I wonder about my own position in a bigger frame, a bigger picture. And the embarrassment, this embarrassment of being in the world, is in all of us. We don't often get further than that, you know.

How did you come to be an artist?

I don't think I am an artist. But I'm being called that.

Why are you being called that?

Because what I do counts as a part of the art world. But I don't feel special like that. I don't feel that I am special at something.

From performance "Fruits of Labor" © Miet Warop

Ok. But how did you come to do what you do?

I'm actually a bit irritated that I have to be called something like an “artist”. I wanted to be something entirely else in my life, and it didn't work out, and somehow my journey lead to this, and it worked. It has allowed me to be myself. Of course, it was not easy. Somehow this chain of events has been spun like that of a stereotypical “artist” – you get disappointed early in your life, and then you become that. I don't like the way that sounds. That is not my case. I feel like something just stood up within myself and became visible, but somebody else wants to frame me – put a stamp on me.

Do you worry about your work being difficult to place within a certain genre?

I don't worry about that; I don't care. But I feel that from the outside, there is a need for it to have a name. I liked the approach we had at KASK. I was part of a school where you didn't have a specific task, but you were tasked to look for your own ideas and, when you have one, to see how you're going to get as close as possible to realizing that, to what it turns out to be. By using any means, any format. It's nice, and I like it very much. But it also has a certain problem, namely, you don't become very good at anything, in any artistic craft. What you're good at is saying – ok, I want to say this, so let's see how we're going to move towards that. For instance, I am not particularly good at anything – I cannot dance, I cannot sing, I cannot act... That is, I can't do it at a high professional level. I can't do anything. (Laughs.) I would not have the patience to be, for instance, a sculptor. Yet I have a strong urge to understand something and to share my search with others. And I have enough skills to translate my reflections and my ideas into, for instance, an hour-long performance. If you call that art, I don't have a problem with it. For me, art is like a frame through which we might see the things that are important to us more clearly.

So, for me, being a performer, a visual artist or a theatre director... I don't really feel being any of these somehow, but I also don't know what is the area that I actually represent. Not that I have invented another word for that. But I am totally not a theatre director. I cannot be. It's super important for me that I've gone to that school, but I'm not sitting upon a dais, shouting at people that maybe they should come a bit to the right because being on the left is too weird. I don't do things like that. Also, the people I work with are not actors. The drummer you saw – he's a wonderful person, and I invited him because of his personality, not because of what he can play. I didn’t have to lead him very much at all – he grasped very quickly how he should move about the stage and where he must be. All by himself. I try not to make anyone become something that he or she is not.

Reinout_Hiel-highres-8806.jpg)

From performance "Fruits of Labor" © Reinout Hiel

Could you perhaps share the details of your “translation” process – how exactly do your ideas take the form of an artwork?

At first, an idea is just a vehicle with which you embark upon an unknown road. The idea is pure and clear, and you hold on to it tightly, not allowing anyone to interfere, and adjusting all things to its realization. But in my case, there is always one critical moment at which I understand that the idea has already added too many new things or even has become something new, and at that moment, I simply let go. I let myself give in to everything, to becoming something new so that I don't become a slave to the initial idea. And at that moment, anything becomes possible – even more than at the beginning, when I was still very strict in terms of planning and research. The people I choose to invite are always carefully chosen based on my research, yet they always come with their own richness and contribution. In short, I might say – at first I have an idea, then people I have chosen begin to participate, then I watch them trying to work with this idea (sometimes failing), and then I finally give in to their energy. Fruits of Labor is typical in this sense. If I saw this richness, this capital of new ideas in front of me, but I would choose not to let it in and strictly hold on to my initial idea, then that would be foolish and also boring. Sometimes it's risky, but that, of course, is also appealing.

An important turn of events in creating Fruits of Labor were the Brussels subway bombings that happened a few years ago. There are references to terrorism in the work. I figured we should try to respond to it with... If not exactly laughter, then at least with joy and generosity. That's a better alternative to fear. To breathe and perhaps even to laugh is better that to live in fear. Otherwise, living would be too heavy. Letting yourself go, trying to be free when facing embarrassment and fear is what we are trying to show, and it is tied to these reflections. By the way, it's crucial to me that I can have fun while I'm working. I don't care if that sounds stupid. For me, it's crucial to have fun.

Do you take yourself seriously?

Yes, but that doesn't exclude the possibility of making fun of oneself. Making fun can be serious, too. Humour helps us to connect better, to understand each other better. For one, I don't believe that people without a sense of humour can be intelligent. Perhaps here we can recall what you said earlier about the reaction of the audience. By laughing together, we are also searching together.

Miet Warlop © Miet Warlop