None of my works has ever left me

An interview with artist Bita Razavi

11/11/2019

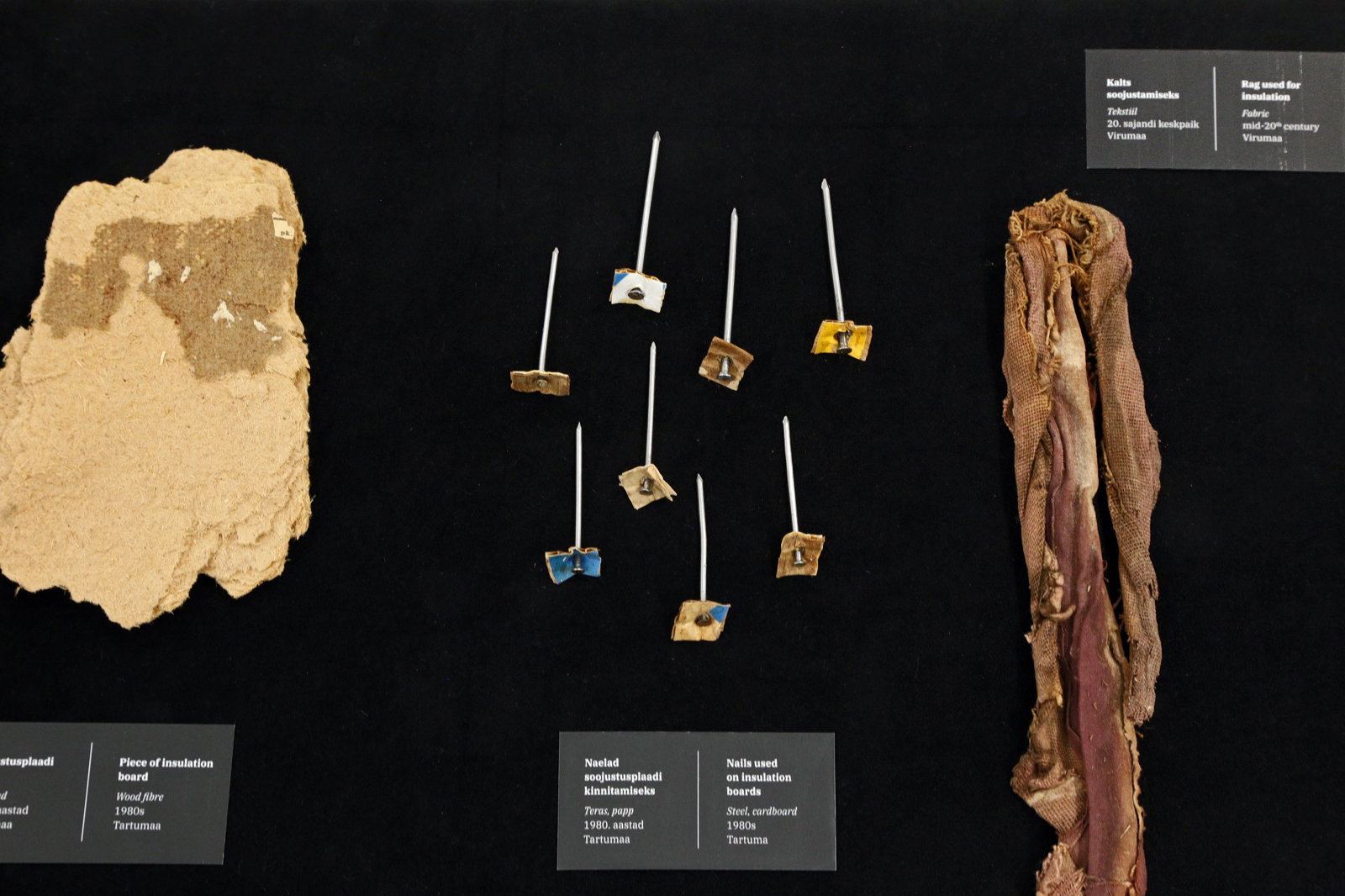

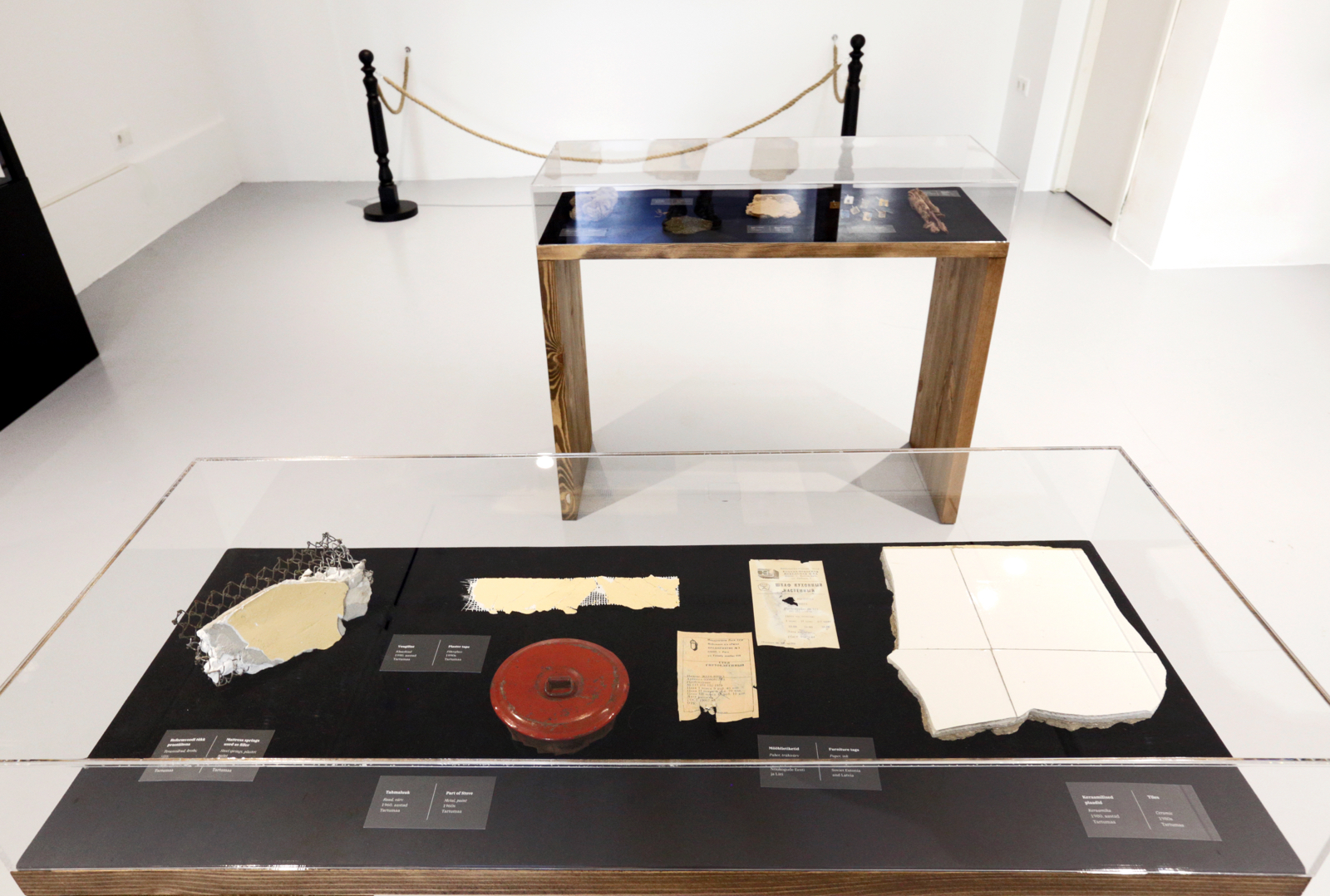

Over the last three years, artist Bita Razavi has been renovating an abandoned house in the Estonian countryside and an apartment in Tartu, documenting the mundane tasks done and also gathering different tools and traces that she encountered during the rebuilding process – as if it were an exercise of contemporary archaeology. Mattress’ springs, parts of a stove, furniture tags, tiles, nails, a leather drawer handle, repair tools, samplers of wallpapers, insulation fibre and board, a paint can, a drill, electric wires, old newspapers, a toilet sit cover and all sorts of unidentifiable things. “You are displaying trash and garbage”, said a visitor during the opening of Bita’s Museum of Baltic Remont at the Kogo Gallery of Tartu (17 October / 16 November 2019).

Photo Liina Raus. Courtesy of Kogo Gallery

In the description of your work ‘The Yellow House’ (2016), you mention that you bought the house to rest and to rehearse hospitality, yet ended up working more…

I was born in Tehran, and what I relate the most with, in the Iranian culture is its notion of hospitality. My home is always prepared for guests. I don’t receive guests that often after all, but I am always prepared for it. I've noticed that even when I do repair work, I look at it from the eyes of possible visitors.

And what kind of similarities do you find between Iran and Estonia?

I grew up in Iran during the Iran-Iraq war, and back then there was the feeling of living in a closed society, and an overwhelming sense of limits – of resources, materials, tools, knowledge… and also the movies and music we listen to. Then the borders slowly opened up. Something similar has happened in Estonia, from the Soviet time to the present. This has resulted in different generations having different relations to things, and also a sense of vanishing, that something is disappearing. I am personally influenced by this idea of crossing borders, and also by the aesthetics of vanishing.

Bita Razavi. Museum of Baltic Remont. 2019. Installation, dimensions variable. Installation view at Kogo gallery. Photo Bita Razavi

Many of your works are based on the idea that bodily interactions have a therapeutic effect.

This was not planned, but it goes back to my first work, when I married a schoolmate at the Finnish Art Academy as a public performance and my graduation project. I imagined it as a symbolic act, getting married to a Finn to criticise the proposed immigration policy of the newly growing party True Finns, and also to apply to the residency permit. But it became something in which I was physically and emotionally involved, not simply legally. The same with the work of photographing Iittala objects in different living rooms while I was working as a cleaner in Helsinki, then I developed a sort of attachment or fascination for these everyday objects.

The way you represent everyday objects also create a sense of estrangement…

This is done intentionally. When I engage with everyday objects, I always try to take an outsider perspective. This is not difficult for me, because of looking at things with fresh eyes. When you move across societies and places, not being a local in any of them, you become capable of noticing things that locals cannot, and feel the normal with a sense of estrangement.

Bita Razavi. Museum of Baltic Remont. 2019. Installation, dimensions variable. Installation view at Kogo gallery. Photo Bita Razavi

This resembles the anthropologist’s eye…

But you don’t have to be an anthropologist to have such eye; rather it is a sort of an attitude, a way of looking at things and observing… it is more the outsider’s eye, missing a sense of community.

Did you have any repair skills when you began working with the Yellow House?

I have exhibited a lot in artist-run spaces, I believe in them; but if you exhibit in this kind of gallery spaces you often end up installing your own work, which has the side effect of improving your bricolage skills. I learnt how to use basic tools, but no more than that; so when I started to repair my house, I did not have many buildings skills. In the Estonian countryside, people don’t hire construction workers, rather you do it yourself, or ask for help from your friend or neighbour. Everyone has some basic skills, and past experiences, building a bathroom, a stove, a wall, a roof… for example, in the countryside party I met a guy who proposed to make an exchange: he will build a stove for me in exchange of two of my photographs. I tried to explain to him that the kind of photographs I make is not the beautiful landscapes that you hang on the living room wall. It was an interesting discussion, because he then replied that it could also be cityscapes, if that's what I meant.

Photo Liina Raus. Courtesy of Kogo Gallery

The reason for exhibiting in artist-run spaces is because of a sort of anti-institutional approach?

Kind of, but it is not only the museums; also curators have a lot of power, choosing the artists that will be presented, establishing how works will be shown, setting interpretations and representations too. Now I am part of this system, so this is not a complaint, but more a critique of power dynamics and the systemic control over artists’ work

What do you expect from a curator once invited to take part in an exhibition?

I expect a mutual understanding, and that the curator puts the artworks at the centre of the exhibition and of the working process too. Also, that there is a collaborative relationship with the curator, instead of a hierarchical one. A positive experience has been, for example, a recent exhibition at the Tallinn Kunsthall.

Bita Razavi. Museum of Baltic Remont. 2019. Installation, dimensions variable. Installation view at Kogo gallery. Photo Bita Razavi

How do you see the commercial potential of your works?

No one has ever bought any of my works, which is something I ponder on, which worries me, but at the same time I am proud of it; as if my works were not made to be sellable. None of my works have ever left me. And my new works are a house and an apartment, which could not be part of the collection of any museum as such.

And which of your works could be the first one being bought by a museum?

I think if any, it would be ‘Bita’s Dowry’, because it is clean, very neat, direct, and rather exotic. Also, it fits to the way institutions label me -- as an Iranian artist, as if I was making works about Iran.

You have been in Estonia since 2013, however you only started to exhibit here a year ago, when Tanel Rander invited you to Valga…

At the beginning, I tried to be part of the art family here, but it never happened. The more I tried, the more I failed. So I gave up, and accepted that Estonia is for me a place to rest, where to spend my personal time, and Helsinki is the place where I work. Then, after Tanel invited me to Valga, I received several proposals to exhibit my work in Tallinn and Tartu.

Bita Razavi. Museum of Baltic Remont. 2019. Installation, dimensions variable. Installation view at Kogo gallery. Photo Bita Razavi