The fat lady hasn’t sung yet

Anna Arutyunova

25/07/2014

Exhibitions of the annual photography festival Les Rencontres d’Arles 2014 are open through 21 September 2014

This year’s edition of the annual photography festival Les Rencontres d’Arles has opened in Arles. The small southern French city where Van Gogh used to paint his fantastic starry swirls and dreamt of founding a new group of artists with Gauguin has been completely taken over by photography exhibitions. You will find one on every corner here: in a church, in an abbey, in a former city hospital. And yet this year the festival has lost almost half of its main venue, Parc des Ateliers – a row of huge hangars on the outskirts of the city. It was here that the main exhibitions used to be housed, making it the main spectator magnet of the festival. Half of the space has now been purchased for the construction of the new Luma Foundation museum designed by Frank Gehry. This year’s edition is held under the subtitle of Parade – and it should have been the victory parade of the exiting director, the French curator François Hébel who headed ‘The Encounters of Arles’ for the last 15 years. As of next year, the office will be taken over by Sam Stourdzé hitherto successfully holding the post of the director of Musée de l'Élysée in Lausanne. What the parade has amounted to, however, is more like a somewhat off-key swan song. Instead of an edition that would stay in our memory for years and years to come, this year’s offering seems quite uneven as far as quality of the shows is concerned. Instead of forming a celebratory procession where they would be supporting each other, the exhibitions have transformed into isolated little islands.

Vik Muniz. Sunbathing, from the Album series, 2014. Courtesy of the artist and Sikkema Jenkins & Co, New York

And yet there is life on some of these islands. The Église des Trinitaires hosts a show by the Brazilian artist Vik Muniz, one of the guest-stars of the festival. The exhibition features two series of photographs: his Album and Postcards from Nowhere. While very different in content – the former shows a collection of photographs from a fictitious family album; the latter deals with cities and tourist attractions that do not exist in the real world – they are both based on the same technique: the artist takes a single photograph, magnified several times, and then proceeds to recreate it using thousands and thousands of anonymous photographs from flea markets as his material. For instance, here we have a huge – almost 2 x 2.5 metres – portrait of a child (the artist aged 4) in front of us. It is way too blurred, way too painterly for a real photograph: it looks almost as if it had been painted in oil on canvas, using some really bold brushwork. On closer inspection, however, the ‘brush strokes’ turn out to be small cut-out pieces from other photographs. In the case of Muniz’ self-portrait as a four-year old boy, it is hundreds of round-cheeked nameless babies, prams and other objects. Creating his self-portrait as a collage of anonymous pictures by other people, Muniz seems to be questioning the uniqueness of our memories about the past: where do we store them? and what do they consist of?

Raymond Depardon. NORD-PAS-DE-CALAIS, Pas-de-Calais, Montcavrel

The exhibition by Raymond Depardon deals with memories of an entirely different sort. The photographer’s idea is presenting the evidence of what remains of World War I in the collective memory of small French towns, namely – some 40 000 monuments erected to commemorate those who lost their lives in the battles. It is obviously impossible for one man to capture such a large number of monuments, and so the project went interactive: anyone who is interested can take a photograph of a monument, mail the picture and become a co-author. The rules set by Depardon are very simple and serve one purpose only – to help even an amateur take a very decent picture: the light source must be positioned behind the photographer and the monument must be photographed from a number of different angles: all of it, including the pedestal; from a distance, including a wider view; close-up, so that either the sky or a ceiling would serve as a backdrop. The exhibition itself consists of two parts: Depardon’s own pictures are shown in one room while the amateur photographs are projected on big screens in the other.

From Kids at War (La Guerre des gosses) by Léon Gimpel. The second picture: Execution of a Boche with a French 75! Paris, 1915. Courtesy of the Collection Société française de photographie (SFP)

A small room just around the corner houses a rare collection of autochrome pictures by Léon Gimpel – some of the first colour photographs of the 20th century, made in the technique invented by the Lumière brothers. What Gimpel did was stage a play war in Rue Greneta in the Sentier neighbourhood of Paris at the time when a very real war was actually going on all over the place. He was assisted in this by the local kids who dressed up every day as French and German soldiers and nurses, made their own toy fire-arms, trenches and airplanes. The result we see is a very touching image of a war in which there is no real death.

Read in archives: Interview with François Hébel, longtime director of Arles Photography Festival

Several shows are dedicated to photography collections, both private and public. William Hunt shows his collection of group photographs – somewhat strange and sometimes ridiculous pictures, often taken to record equally weird occasions. The size of the groups vary: from relatively sparsely populated family photographs to pictures into which the photographer has somehow managed to cram hundreds of people – taken, for instance, at all sorts of veteran get-togethers or official assemblies and featuring some really vast groups. People in the pictures look more like tiny match-sticks; the photograph serves merely to record an event. A collection of group photographs that adhere to aesthetics of a completely different kind have been brought to Arles by the historian and expert of Chinese history Claude Hudelot: these are panoramic pictures dominated by an ideal order. And last but not least, the famous collector Artur Walther is showing a selection of photographs from his extensive collection that comprises more than 2000 individual pictures. This museum-quality exhibition features some vintage works by Richard Avedon, photographs by Hilla and Bernd Becher, August Sander, Ai Weiwei, Zhang Huan et al.

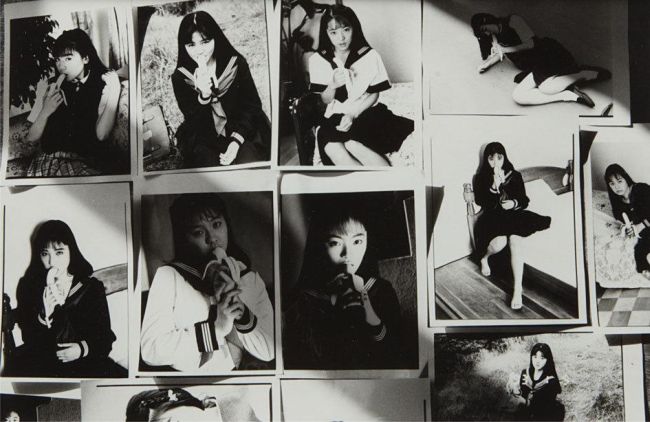

From the Artur Walther collection. Nobuyoshi Araki, 101 Works for Robert Frank (Private Diary), 1993. Courtesy of The Walther Collection and Anton Kern Gallery, New York

And yet even the collection-themed keynote of the festival fails to save it from the general dissonance. There is a tense anticipation of imminent change in the air this year in Arles; it is not in the announcement of the new administrator alone that said change makes itself felt but also in the shows presented by the potential new hosts of the ‘ball’, the Luma Foundation. Where a few years from now a crystal-like museum and centre for contemporary culture will be standing, a hangar is currently housing an exhibition entitled The Solaris Chronicles. The show presents architectural models of both existing and forthcoming buildings by Frank Gehry, including the Guggenheim Museums in Bilbao and Abu Dhabi, the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles and the Facebook headquarters under construction in London and Dublin. To create their own works around these mock-ups, a group of well-known artists were invited. Philippe Parreno and Liam Gillick have come up with a light installation: the source of light is moving across the ceiling, casting all sorts of bizarre shadows. Tino Sehgal has staged something reminiscent of a dance featuring people as well as architectural models: a team of his assistants are pushing platforms with Gehry’s mock-ups around the room, strictly following the route laid down by the artist.

As for the route that the festival itself will take in the future, it remains to be seen. Given the presence of a powerful neighbour like the Luma Foundation, focussed on contemporary art exclusively, the position of photography in Arles is not so much threatened as it is in need of some serious thought. And the new director has a year to figure out the future direction of the festival – and demonstrate that the proverbial fat lady has not sung for Les Rencontres d’Arles yet.