The mysteries of le monde houellbecquien

Weronika Trojańska*

21/06/2017

Michel Houellebecq “French Bashing”

VENUS, New York City

Through August 4, 2017

Acclaimed author Michel Houellebecq is an “aging enfant terrible”[1] of French literature. Some people find it hard to pronounce his name, some find it hard to digest his work, but he seems to not care – just like his readers don’t. It could well be that there is no single text about him or review of his work that hasn’t hailed him as “one of the most controversial contemporary French writers”.

In 2011 Houellebecq went missing without explanation while promoting his novel “The Map and the Territory”, the narrative of which revolves around the fictional artist Jed Martin who becomes rich and famous for his series of photographs of Michelin road maps and paintings featuring people of various professions (including a writer named Houellebecq), and who later becomes intertwined in the investigation of a heinous crime. After the real Houellebecq failed to show up for a promotional tour in the Netherlands, rumors started to swirl, including speculation on him being allegedly snatched by Al Qaeda. Taking into account Houellebecq’s statements on Islam (calling it “the most stupid religion", and which landed him in court), for some, this possible explanation didn’t seem totally impossible. This story became the apparent genesis for Guillaume Nicloux’s brilliant movie “The Kidnapping of Michel Houellebecq” (2014), in which the novelist is held by three abductors who, instead of torture, prefer intellectual debate.

.jpg)

Michel Houellebecq. France #017 (2016)

This sounds like a possible opening sequence for Houellebecq’s new exhibition, “French Bashing”, at the New York uptown gallery VENUS. The opening was supposed to be preceded by a discussion at Albertine bookstore between the author of “The Map and the Territory” and Adam Lidermann, the founder of the gallery. If I had known more about the story above (in reality, the disappearance was caused by a failed internet connection), I wouldn’t have been so surprised that Houellebecq didn’t show up at the event which happened to take place on a sunny Friday early-afternoon (and which was eventually canceled after over an hour of waiting, apparently, because Houellebecq didn’t feel well). I read later in his interview with VICE Magazine – conducted the day before the disappointing no-show at Albertine – in which Houellebecq said that in France, when the weather is nice, people generally don't bother going to gallery openings. He did, however, attended the vernissage for his exhibition, which took place a few hours after the canceled talk at Albertine.

The fact is, whether Houellebecq appears or not, he succeeds in arousing the public’s interest. “It’s so rare to have someone who has a public persona like this. He performs, he participates”, said Jean de Lois, curator of Houellebecq’s exhibition “Rester Vivant” (To Stay Alive), which was presented last year at the Palais de Tokyo in Paris. A selection of works from the Paris show constitutes the exhibition currently on view in New York City, which is his first gallery presentation in the United States.

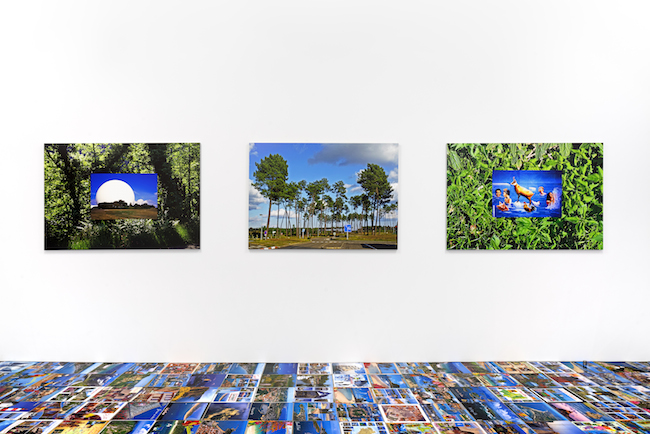

Michel Houellebecq. Installation View

The entrance room of VENUS has been transformed into pitch-black scenery where the only glimpses of light are illuminated, sleek photographs depicting the desolate landscapes of public spaces (e.g., train stations, empty roads, railways, apartment buildings). The grayish colors and ominous overtone remind me of the post-apocalyptic vision of the world in Cormack McCarthy’s Pulitzer Prize-winning book “The Road”, which tells the story of a father and son traversing a burned-out America inhabited by the last few remnants of mankind. Could we imagine, looking at Houellebecq’s photographs, that we are the only people left on earth – like the protagonist of McCarthy’s contemporary parable? People appear only in one picture, as blurred figures captured from above, and resembling an image registered by a video surveillance camera. They are in motion, but they don’t even look real. But there is other evidence of the (past?) presence of human beings, such as the sentence on one of the parts of the large triptych – placed right next to the cinematic and monochromatic scene of the roofs of Paris – which says “I had no more reason to kill myself than most of these people did”. Even the accompanying audio soundtrack, composed by Raphael Söhier, consists of purely industrial sounds such as horns or train announcements. This despondent city panorama could very likely be inhabited by the characters of Houellebecq’s novels who – living in a world shaped by reality TV, corporations, fast food, supermarkets and masturbation – have sunk into an overwhelming feeling of acedia. A lack of relationships, caused by constant work in the name of capitalism, led them to total isolation. “Unable and eventually unwilling to connect to any other body, Houellebecq’s protagonists retreat from affective potentiality into almost total somatic isolation where all human life is identical.”[2]

Michel Houellebecq. Installation View

“It has now become easier”, writes Frederic Jameson, American literary critic and Marxist political theorist, “to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism”[3]. With these words in mind, I move to the other room in the gallery, blasted by its bright lighting. Here on the walls hang vibrant, almost fluorescent photographs and photo-collages of kitschy tourism (hotels, tour buses, summer beach houses), while the floor is covered with laminated colorful place mats depicting famous holiday sites and attractions found around the world, from Normandy to Guadeloupe. But after a moment, I feel cheated by the semi-optimistic tone of the display. The places are, again, eerily uninhabited, and suspiciously too vivid. The aesthetic of the images, and this room in general, reminds me of the pictures printed on the plastic shopping bags that I remember from my childhood. And tourism and shopping, as one of the symbols of consumerism, are another of Houellebecq’s staples. His protagonists take a fin de siècle winter holiday in the Canary Islands (“Whatever”) or travel to exotic places to have sex (“Lanzarote” and “Platform”). “The realm of the erotic has thus been rendered as banally commodified shopping or tourism. His characters are becoming insensible to intimacy[4]”. The generated sounds of chattering people, laughing kids, and crashing waves that fill the room reminds us that “the neohumans have only the faintest trace of memory of human laughter and happiness”[5]. The joy can be only artificial.

.jpg)

Michel Houellebecq. Tourisme #014 (2016)

Believe it or not, but Houellebecq has been taking photographs for almost two decades and only in recent years have they been revealed to the public. However, “art is a constant preoccupation throughout his novels that allows him to establish exactly his own aesthetics,” as de Lois said. And much like Houellebecq’s other disputed novels, “French Bashing” is a scenario that guides us through some of his obsessions. Nonetheless, the exhibited photographs (all of them were taken within the last two years) don’t serve as an accompanying illustration or addendum to his writing. The world he creates with his images has the same properties as those constructed in his prose. The gallery acts like an open book in which each work is a new paragraph. The curator of his show in Paris said that “he did everything himself, with a strong obsession. He told me, ‘I don’t want it to be a show on Houellebecq, but a show by Houellebecq.”

Akin to his novels that tend to produce divided opinions, people can either love his art works or argue that the photographs are not good enough. Houellebecq has mastered the art of splitting the public’s response into two distinct halves. Jut as with the white and black rooms in the gallery, there are no ambivalent feelings towards his work. Or, like in his novel “Atomized”: “there are only two responses that they have created and encouraged: hedonistic libertinism or ascetic retreat”[6]. No matter what the reactions are, his name has become a brand in itself. But the obsession with le monde houellbecquien goes far beyond capitalist consumerism.

.jpg)

Michel Houellebecq. Tourisme #014 (2016)

Houellebecq’s exhibition came to New York during a significant political moment – in the middle of many Americans’ still strong dissatisfaction towards the current government, just after the elections in France (on which Houellebecq commented that it was

more fascinating

than any other political event), and with terrorist assaults happening in Europe. “The attacks on Paris have a depressing effect on tourism,” the author has said.[7] The English translation of his novel “Platform”, which was designed to pacify French Muslims, was published just before the attacks of 9/11. Another one, “The Map and Territory”, apparently predicted the financial crisis of 2008. Theo Taito, in a text for the “London Review of Books”, called Houellebecq a visionary diagnostician. Is it possible that his work is prophetic? One of the photographs on view at VENUS shows a sky at dusk, with a written slogan saying “Time to place your bets”. “French Bashing” is on view until August; let’s see what will happen by then.

.jpg)

Michel Houellebecq. France #013 (2016)

.jpg)

Michel Houellebecq. Mission #002 (2016)

.jpg)

Michel Houellebecq. Inscriptions #018 (2016)

Michel Houellebecq. Installation View

Michel Houellebecq. Installation View

.jpg)

Michel Houellebecq. Arrangements #004 (2016)

[2] C. Sweeney, Michel Houellebecq and the Literature of Despair, Bloomsbury Academic, 2013, p.188

[3] F. Jameson, The Seed of Time, Columbia University Press, 1994

[4] C. Sweeney, Michel Houellebecq and the Literature of Despair, Bloomsbury Academic, 2013, p. XVIII

[5] as above, p. 188

[6] as above, p.3

*Bio: Weronika Trojańska is an artist and art writer. She graduated from Academy of Fine Arts (Art Criticism and Art Promotion) in Poznań and Sandberg Instituut (Fine Arts) in Amsterdam. In her practice she investigate the notion of artists’ auto/biography as fictional construct. She writes regularly for art magazine Metropolis My, among others. Currently she lives and works in Poland.