Find Eastern Europe!

The exhibition Orient at kim? Contemporary Art Centre. Sporta iela 2-1 and Tallinas iela 6

17/05/2018

My viewing of the exhibition Orient began with a search – knowing that its larger half was set up in the old motor depot on Tallinas iela, where cultural activists have set up camp under the leadership of Kaspars Lielgalvis, I had mistakenly assumed that it would be in the same place where the Kaspars Groševs-curated group show Baltie klīdēji (White Wanderers) had taken place the previous year. It turned out that Orient was in the neighboring building, but I figured that out only after having walked through the nooks and crannies of the quarter, witnessing the vivid cacophony that many deem the epitome of Eastern Europeanness: a crumbling but slightly spiffied-up environment in which the garages could very well still house their old soviet-era mini-buses, while one corner appears to have already been gentrified for the corporate crowd. Which is why I was quite surprised to find that the personality of the space was extraneous, even counterproductive in terms of the real exhibition: the artworks were linearly hung up on the walls, whereas the more sculptural pieces were set up in the middle of the room, that is to say, just as in any white-walled gallery. Perhaps only a bit more crowded owing to the old wall partitions that had yet to be knocked down. Maybe this impression arose due to my expectations that I would be going on a search for something that would be decidedly ‘Eastern European’. I hadn’t come up with this out of the blue, by the way – the exhibition’s handout states: ‘The exhibition Orient is a meditation on the Eastern European identity. As the unifying aspect of this unclear region, it considers the failure of its own identity.’ Since Orient is neither the first nor last of this year’s exhibitions that promise to search for identity, it’s worth looking at a bit closer.

Photo: Viktorija Eksta

Leaving aside the essence of identity (if such a thing even exists), let’s ponder the question in play – who is asking it, and for what reason? I know of people who have found their personal identity with great difficulty, occasionally even suffering, which is why this dilemma seems neither ludicrous nor trivial to me. Nevertheless, I don’t think that Eastern Europe can be likened to a person. I’m not sure that the people who live in Eastern Europe are struggling with identity issues on a daily basis. The same goes for the countries – there are several of them in the region, and their borders are not in question (at least not on drastic scales). The only unifying element is the influence that comes from a country that no longer exists – the USSR – and that, too, exhibits itself in markedly different ways. A need for constructing an additional unifying identity – which has no basis on either a personal or political level – arises in certain situations. (I still remember the European expansion project that was accompanied by cultural activities of a similar nature.) It is not by accident that the construct of ‘Eastern Europe’ is no longer on the agenda in a political sense but in a cultural one, specifically, in the context of contemporary art. Attempts at unity usually occur in a situation of imminent threat or in the name of some goal, either of which is usually stated. Threats: weakening competitiveness, a decrease in access to resources, globalisation processes, and cultural colonialism coming from more economically developed countries (not only on a European scale but world-wide). In terms of goals, I think it’s crucial that the focus here not be on a label or some souvenir, as in, to use a metaphor, some new-fangled Russian nesting doll whose only message is ‘buy me, lovely Western tourists (i.e. collectors, curators)! I am beautiful and exotic, and there is so much more inside of me!’. I’m not sure if the point of identity is to be able to offer it to others but not yourself.

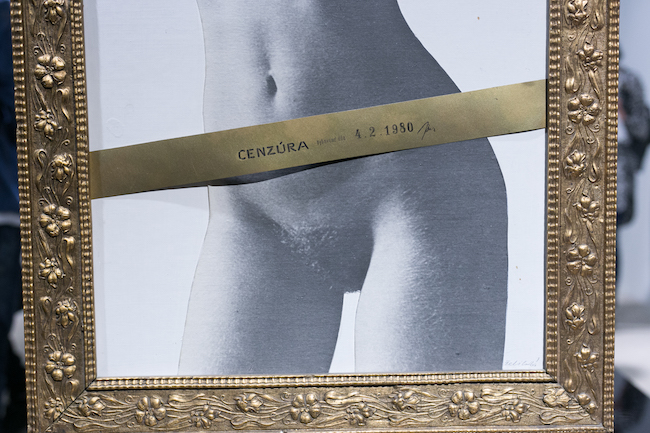

Veronika Bromová, I table, 2000. Photo: Viktorija Eksta

We can thank the exhibition’s curator, Michal Novotny, for introducing us to a large number of Czech artists – at the Tallinas iela venue they make up 16 of the 43 artists being represented, while at the kim? Contemporary Art Centre they are 8 of 15. Even though the works in the exhibit were not only by young artists but well-established names as well, I will not hide the fact that it was my first time viewing most all of them. I won’t list the numbers of artists representing the other countries because that would only highlight the fact that only two artists from Latvia were shown – Atis Jākobsons and Viktor Timofeev, the latter of whom is now based in the USA. Moreover, the recurring problem with Jākobsons has now arisen twice in recent times, namely, when his introverted manner is placed in a politicised context, it risks being misunderstood. I don’t want to sound like a picky accountant who believes that artistic presence can be increased by sheer numbers alone, but some concerns linger nevertheless – In what way does ‘some’ turn into ‘many’? Which ideological constructs are people offered to identify themselves with? Which generalizations are we willing to tolerate? And is it really proper to be building up concepts about a region’s identity by inviting one Russian and one Lithuanian (alright, two Lithuanians) purely for the sake of broadening the scope of representation?

Photo: Viktorija Eksta

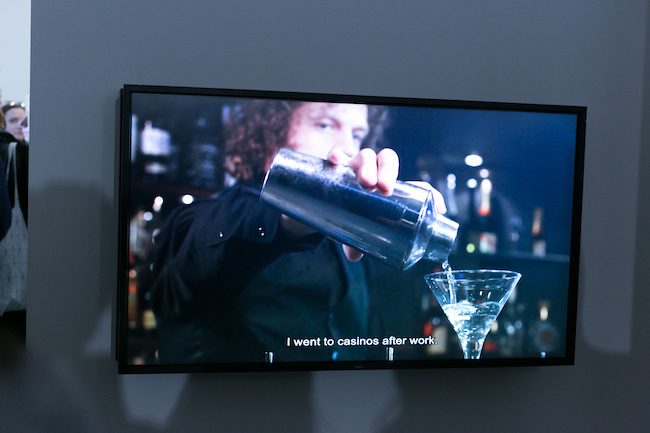

There is little in the exhibition to indicate that its objective is to introduce a large number of artists to a specifically Latvian viewership. As one has, unfortunately, come to expect with exhibitions organised by kim?, walking through the show with handout in hand and trying to identify each work is a fairly arduous task. The numbers on the map are not in order, and trying to match up each work with its description becomes a frustrating game if you do, indeed, wish to take a serious look at the exhibition; one is left with the feeling that the printed guides were made for a different hall and some other unknown use. The video work, which has audio in Estonian and Russian but subtitles only in English, becomes only marginally more viewer-friendly than one in which the audience understands neither the audio nor the subtitles. My attempts at figuring out which part of the exhibition I was in and when (after I had already walked through it) became a true puzzle. It turns out that the first part, which was in the Tallinas iela venue, was followed by a second part at the central location of kim? on Sporta iela, after which there were two more parts back at the Tallina iela venue. Why it wasn’t possible to lay out the exhibition in the order selected by the curator instead of changing sections of its numbering remains a mystery. I wouldn’t want to think that an exhibition on identity is being presented to people whose identity no one really cares about.

Photo: Viktorija Eksta

A surprising amount of the works in the show contain themes on consumerism, executed with greater or lesser levels of irony depending on the work; only in a few does cutting critique rear its head. The most blatant example is by Romanian artist Vlad Nancă: ‘I love shopping!’ yells its title, and that also is what his photographs depict. His other work, Untitled (Comet plant stand), appears to illustrate an affinity for decorating a room with plants bought at the local mega-store, then ignoring them until it’s time to throw them out. We have no idea whether or not that was the artist’s intention since two works are too few to be able to judge an artist; in the context of this exhibition, however, two is a lot.

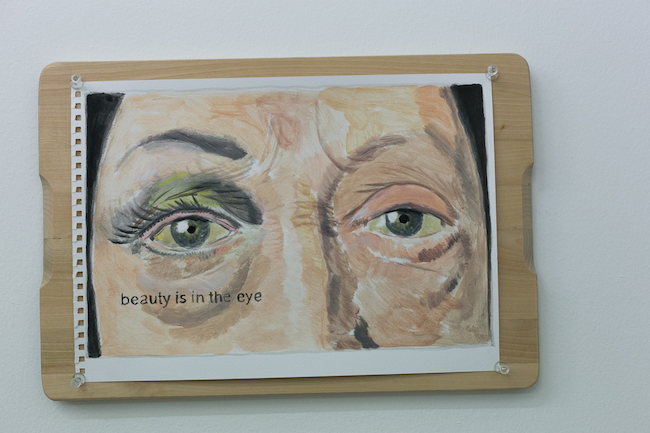

Although in some cases handicraft skills characteristic of a certain region can be discerned, most of the relationships with the physical materials themselves are like those in the performance Work by Pavel Brăila (Macedonia) – to see a video of it you have to stick your head through a slit in a thoroughly unnecessary piece of fabric, whereupon you see a man digging into the ground (albeit through sheets of white paper, thereby creating patterns) – subsequently, the kind of people interested in contemporary art try to hide their yawns. Seemingly eye-catching is the video by Croatian artist David Maljkovič, Lost Memories From These Days, in which women, apparently either tired or bored, pose next to high-powered cars. This archetypal Eastern European dream of ‘cash, cars and women’ can be seen in several works here. The part of the exhibition on view at Sporta iela, All dressed up and nowhere to go, sounds like a sarcastic diagnosis: ‘And here, gentlemen, we see the new Eastern European problem!’ Luckily, a few artists, for instance, Marge Monko from Estonia, have managed to make something deeper.

One photograph, however, stands out, and that’s not just because it’s been placed on the floor. It is, in fact, the only documentation of Russian artist Avdey Ter-Oganyan’s performance Towards the Object, from all the way back in 1992. Calling it a performance is stretching it – Ter-Oganyan simply lay on the floor drunk during an event. If you’re even slightly familiar with the rich traditions of Moscow actionism, you’ll sense that this is not just a joke.

It’s not the exhibition itself but its accompanying texts that are full of references to yearnings for freedom – a prominent characteristic of Eastern Europe’s past – and which were no stranger to extreme, altruistic behaviour in the name of justice. Another feature was art’s ability to adequately reflect these yearnings. However, taking into account the exhibition’s stated concept, it really is in the past.

Photo: Viktorija Eksta

Photo: Viktorija Eksta

In the exhibition’s handout there are many intelligent and educational statements, some of which I agree with, and some that I don’t. What I know of the curator’s tendency towards frankness comes from the published interview of him done by the creative director of kim?, Valentinas Klimašauskas, in which Novotny says: ‘I will never speak and write English at a level that I would like. Perhaps that is why I tend to use so many quotes.’ That really is true, there are many quotes in the exhibition, expressed both verbally and through form. Novotny continues: “...I’m interested in how to make understandable those who don’t speak in an international language...how to make them look stylish.’ The wish to look stylish in mass-produced Western merchandise is, indeed, every Eastern European’s raison d’etre.

“Orient” is on show at Tallinas street 6 and Kim?, Sporta street 2 k-1 till May 20