A Trap for Critics

58th Venice Biennale: A Journey with Post-Truth

15/05/2019

These days it’s sometimes a good thing to be led by the nose. Because you should not have your nose in the air but rather follow it around. Which is what the curator Ralph Rugoff has understood perfectly. The very title of the current edition ‒ May You Live in Interesting Times ‒ is a hoax. What purports to be an ancient Chinese tongue-in-cheek proverb was in fact invented by 20th-century European intellectuals. Besides, the curse itself is more than a little ambiguous: what if living in times of change and turmoil is genuinely so much more interesting?

Curator Rugoff refers to the concept of post-truth in the context of the official mass media, vehicles of mass propaganda, lying away throughout the world like there’s no tomorrow. Ralph Rugoff recalls George Orwell’s 1984 where the novelist describes the strategy of instilling two mutually contradictory notions into the brain of the same everyman. The notions are to be perceived not critically but archetypically, as an axiom. The two countries currently excelling in this kind of zombifying people’s minds by all sorts of media scum are Trump’s America and Putin’s Russia.

Lauren Bon and The Metabolic Studio. Artists Need to Create on the Same Scale that Society Has the Capacity to Destroy. 2006. Photo: Joshua White

What emerges as an alternative is the domain of local stories created in various informal communities. Also important is deconstruction of manipulative technologies by creating dissenting ‘new spaces’. Alongside the traditional ‘good’ and ‘bad’ hypothetical spaces, ‘utopias’ and ‘dystopias’ (anti-utopias), it is fundamentally important today that we turn to intermediate meta-versions: heterotopias, atopias. Back in the second half of the 20th century, Michel Foucault introduced the concept of ‘other spaces’, heterotopia. He defined them in terms of a local, even intimate perception of separate fragments of space and time. This is what Foucault had to say: ‘We are at a moment, I believe, when our experience of the world is less that of a long life developing through time than that of a network that connects points and intersects with its own skein. One could perhaps say that certain ideological conflicts animating present-day polemics oppose the pious descendants of time and the determined inhabitants of space.’

Carol Bove, Nike III, 2019. Photo: Arterritory.com

New virtual or even post-Internet dimensions of space and time offer a way of understanding a personal truth, one that is not part of larger narratives and repressive ideologies.

The exhibition mounted by the curator Ralph Rugoff at the giant Venetian baroque ammunition and ship warehouse – the Arsenale ‒ and the main pavilion in the Giardini is capable of confusing those who define their lives in the old-school terms of ‘like ‒ don’t like’, ‘comprehensible ‒ incomprehensible’, ‘corresponding ‒ non-corresponding’. Having worked for many years at a daily newspaper, I know from my own experience that it is exactly this kind of protean elusive theme that irritates critics, whose rules of the trade demand that they saddle a comprehensible, intelligibly communicated subject as quickly as possible, dig their spurs into it and rush towards the deadline at breakneck speed. Whereas here...

The director of the Biennale constantly leads the visitor away from linear meanings. He, of course, makes the composition something like a quest. Said quest, however, is structured in keeping with the principle of foldable scenery. It is a bit like the façade of a Frank Gehry building: now the shards of steel tighten like a tourniquet, now they lie flat like smooth ribbons. And so the visual design is based on the principle of ‘expansion ‒ compression’. And it works a treat. Despite the dissertational format of a two-part anthropological study, the exhibition is easy to view.

One of the main reasons lies in the fact that it is the works of predominantly the same artists that are presented in both of the giant venues, the Arsenale and the central pavilion in the Giardini. Which means that each artist is effectively showing something like a folding ‘altar piece’, a diptych. Therefore, the compound image turns out to be voluminous and more likely to linger in your mind.

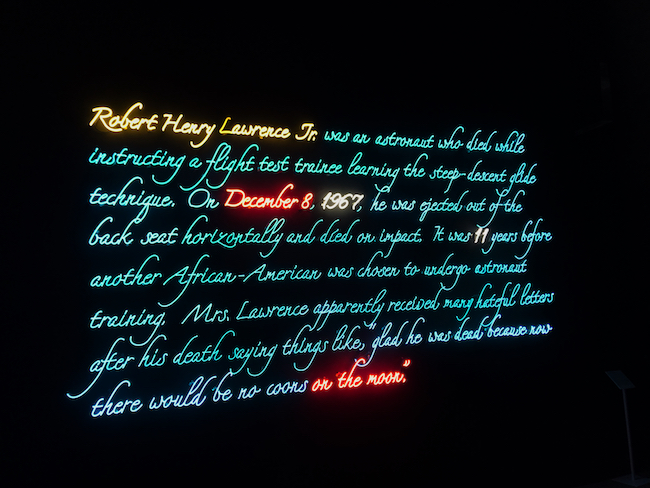

Tavares Strachan. Robert Henry Lawrence Jr. 2018. Photo: Arterritory.com

The second reason for the success of the directing is the contrasting juxtaposition of different subjects and media. Post-conceptual play on neon texts and meta-modernist Gothic fusion on the subject of consumption of Victorian culture today may very well find themselves opposite each other in the same room. Rooms with high-tech Chinese-produced amusement stalls rub shoulders with spaces dominated by naive expressionist paintings by African artists. Social documentation of the problem of truth in today’s world lives side by side with the simple material truth of abstract and/or minimalist sculptures.

The third reason: curator Rugoff has happily escaped the complex of the ‘star factory’. There are practically no brand names of the global art market who, in fact, frequently have very little to say. Artists from many countries that are not among the elite of global art consumption have been invited. They present their truth of life in all honesty. And you believe them.

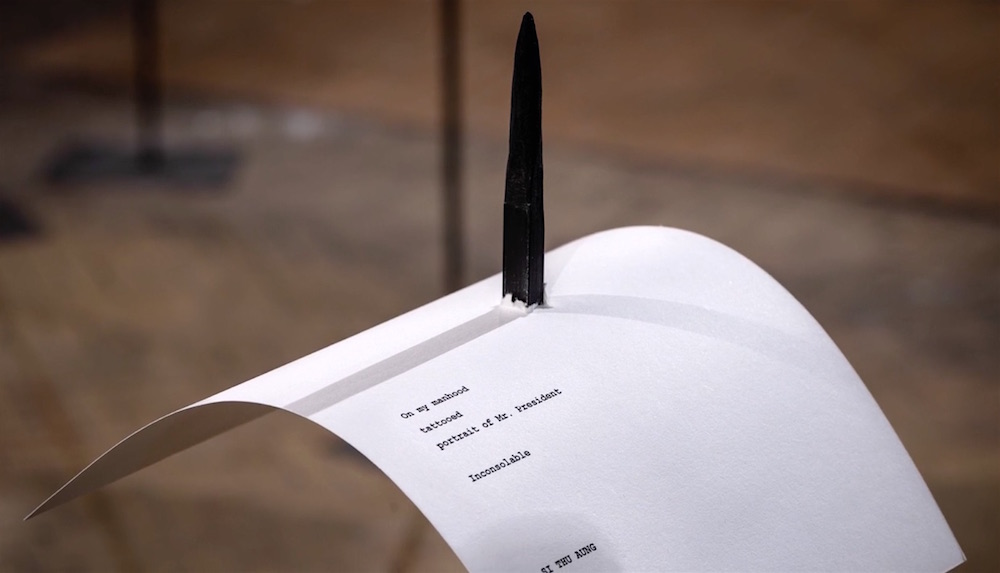

Fragment of installation For, in your tongue, I cannot fit by Shilpa Gupta

Regarding post-truth, an important subject is the border area where a number of diverse truths and wills meet. Quite a lot of works are dedicated to boundaries (ethical, political, social). One of the best among them is the sound art installation by the Indian artist Shilpa Gupta For, in your tongue, I cannot fit. These words are borrowed from a poem by the 14th-century Azerbaijani poet Imadaddin Nasimi. A hundred microphones are suspended in a dark room, under each of them ‒ a music stand with fragments of phrases in countless languages, from Hindi to Egyptian to Russian. The sound from each of the microphones, one by one, travels like a resonant wave to the next one. And so it goes, for a hundred times. A hundred verses by poets repressed for their political views, dating from the 7th century to the present day, fill the space of the room, inevitably engaging the hearing and emotions of the visitor. The sound landscape, amplified by a hundred, forcefully pulls you into its field.

Another important subject: the glocal, that is ‒ a search for universal subjects in the vernacular art with its local truth. In this context, African and South American artists make a strong appearance. The paintings of a 35-year old Kenyan artist, Michael Armitage, were a genuine revelation. Inspired by traditional mythological African art and primitive cheap pictures, his pieces unexpectedly transform into expressive poems that refer both to Christian baroque iconography and abstract expressionism. Armitage’s metastyle turns into a virtuosically and sublimely arranged territory of personal deeply felt truth about living at the intersection of civilisations.

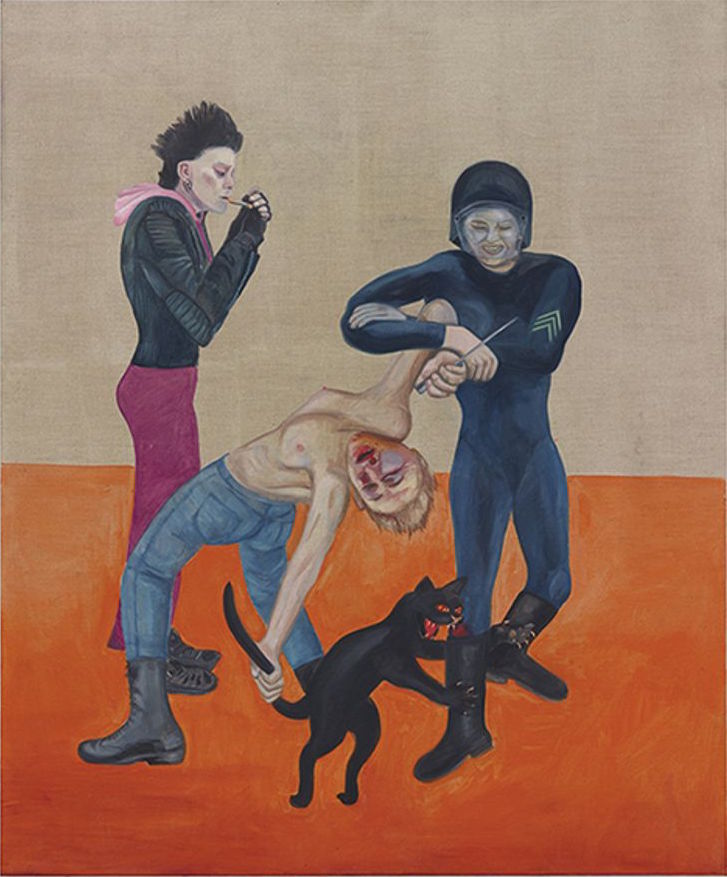

Jill Mulleady. Riot on the Holodeck. 2018 © Jill Mulleady; Courtesy of the artist and Freedman Fitzpatrick; Los Angeles/Paris

A similar subject is explored in both parts of the main project by the Uruguayan artist Jill Mulleady. Appealing to the art of Edvard Munch with his fierce colour attacks and tapestry-like composition adds an unexpectedly spiritual touch to unsightly scenes from the life of an American megapolis.

Yet another subject: genuineness and fakeness of material. Simulative constructions created from industrial materials imitating organic nature define the works of some Chinese artists, as well as the heterotopic market by the Ukrainian artist Zhanna Kadyrova. Zhanna has installed a typical makeshift stall with fruit and vegetables from concrete and tiles.

In this context, the Latvian Pavilion, continuing the enfilade of the Arsenale, reads like an epenthetic novella. Daiga Grantiņa presents her project entitled Saules Suns ‒ Sun Dog, also dedicated to the paradoxes of our perception, to the transformation of the organic into the non-organic. A garden of metallic spirals, pieces of wood and assorted synthetic materials resonates with the subject of the new Anthropocene ‒ the Biocene. And yet the resulting landscape is light, beautiful, airy and feels like a small isle of relaxation after the serious job of exploring the dissertations of the main project.

Fragments from the Saules Suns (Sun Dog) exhibition at the Latvian Pavilion. Photo: Toan Vu-Huu

I would give the name of ‘the Frankenstein complex’ to a wonderfully successful story dealing with fakeness and simulations, part of the curator’s project. Raging mechanisms ripping up the unconscious and exposing enjoyment of uncontrolled violence and oppression ‒ this is the subject of two works by the Chinese tandem of artists, Sun Yuan and Peng Yu. Hissing, a tourniquet explodes from a Roman emperor’s throne and proceeds to torture and aggressively lash the space around it. A powerful stream of air is released through an in-built hose, and the pressure makes the whistling and thrashing snake perform an insane dance. In the other work, Sun and Peng have imprisoned a mechanical dragon with a brush instead of its muzzle inside a transparent enclosure. It twists, performs a complex dance in the air, then bends down and starts to mop up the puddle of blood-coloured substance surrounding it. It splashes the red liquid all over the walls of the transparent cube and continues its wiggly dance... An unsettling sight. A mutiny of the machines and the archetype of power.

Photo and video fragment of installation by Ed Atkins

A cyber-ethical version of the Frankenstein complex is very accurately expressed in an installation by the British artist Ed Atkins. His Old Food brings to life the world of Victorian Gothic ‒ albeit in a matrixed, digital RPG format... All the attributes of noir ‒ abandoned hut, forest, candlelight, suffering children-dolls and a creepy hooded traveller ‒ are lovingly presented on numerous video panels courtesy of computer animation. In the middle of it all, there are huge wardrobes installed with stage costumes of knights, ladies and kings ‒ as if sent over from spare dressing rooms of an old theatre. The room is filled with sounds of minimalist music and muted sighs and sobbing. A separate screen shows a commercial-like clip of a sandwich being assembled from various tempting ingredients. On a serious level, this work by Atkins shows how the world of the popular genre of horror and thriller is prepared and served. It was in the Victorian age that the middle class started to consume the Gothic genre like an elaborately prepared sandwich with countless ingredients. Atkins showed us the universal assemblage of this sandwich, both in digital and old-school versions. The carnival-like presentation livened up the aesthetics of exalted sensitivity of cabaret camp, dime novels and pulp fiction. The gothic novel was the donor. And Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is also a member of the same family. Incidentally, it is nice to know that, to a certain extent, a whole team of Russian artists of the younger generation also take part in the conversation around the table at the candlelit dinner party hosted by Atkins. At the Museum of Moscow, we are currently mounting a programme dedicated to the patriarch of Russian fantasy, Prince Vladimir Fyodorovich Odoyevsky. My curatorial installation of the exhibition, due to open on 28 June 2019, also includes a dialogue between the virtual and the archival. A separate section will be dedicated to the alchemical recipes personally developed by Odoyevsky the gastronome.

Symmetrical answer

Interestingly, the duplication and muddle of post-history is also what makes the viewing of both Russian programmes at the Biennale ‒ the national pavilion and the exhibition There is a Beginning in the End. The Secret Tintoretto Fraternity at the San Fantin Church ‒ so confusing.

The Russian Pavilion presented a story based on Rembrandt’s Return of the Prodigal Son. The protagonists of the story were the Hermitage, director Alexander Sokurov and artist Alexander Shishkin-Hokusai. As for the idea, it is all about recognising the great tragedies and sarcastic grimaces of humanity in the mirror of works by the old masters from the Hermitage collection. Rembrandt and Sokurov are in charge of the tragedy bit while plywood objects by Shishkin-Hokusai and baroque Flemish paintings (still lifes) are responsible for the grimacing. The key concept of the pavilion’s interpretation for me was neo-peredvizhnik art. The visual plane is as obvious as a poster. Lots of shared space. Reproductions of Rembrandt are supplemented by sculptures by students of Academy of Art and some video art featuring rivers of fire and the Tower of Babel. Shishkin-Hokusai has livened up still lifes by Snijders with a mechanical ballet of Magritte’s little men. A very obvious critique of social sculpture. The poster-like style and propaganda of great art makes the image of the exhibition reminiscent of teaching aids promoting aesthetic education. I remember myself in the role of a curator-director, mounting an exhibition on the subject of ‘Rembrandt and the optics of mass culture’ some fifteen years ago. The artists Alexei Politov and Marina Belova made a plywood shadow play theatre, bringing to life the stories of some of Rembrandt’s paintings ‒ like in the teaser for the Night Watch movie. The whole thing was set in CCI Fabrika. In other words, there is already a certain tradition of showing the old masters in the genre of fairground peep show. I would have liked to see Sokurov’s part of the show, the solemn one, installed with greater attention to the actual Rembrandt. Because as it is, the painting is read too broadly. No specific themes, not even naive or, for instance, contemporary, digital ones, have been recognised and captured in the actual expressiveness, technique, dramatic structure of the great Dutchman’s painting. And yet the exhibition was curated by the Hermitage museum, where accuracy of vision is a criterion of expert judgement.

Fragment of Dmitry Krymov’s performance at the San Fantin Church. Photo: Natasha Polskaya

Staging-wise, the exhibition at the San Fantin Church is exactly the opposite. The script seemed quite similar. Except the dialogue here is between the authors ‒ the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, Stella Art Foundation, curators Olga Shishko and Marina Loshak ‒ and Tintoretto, whose unknown painting was shown at the church. Four masters ‒ theatre director Dmitry Krymov, artists Irina Nakhova, Emilio Vedova and Gary Hill – present the world of Tintoretto in its movement from a real evidence of divine presence, a manifestation of miracle (Krymov, Nakhova) to abstract virtuality (Emilio Vedova, Gary Hill). Contrasting with the poster-like naivety of works by the masters represented at the Russian Pavilion, in this project the nature of Tintoretto’s magic light is dissected carefully and painstakingly. We become eyewitnesses to the fact that in his treatment of the substance of light, staging the space as an enlightenment, an illumination (a term aptly used by the Italian art historian Giulio Argan), Tintoretto turns out to herald the masters of contemporary art. It is confirmed both by the cinematographic quality of his vision and his unique exalted sense of time. It was not by accident that a few years ago the curator of the 54th Venice Biennale Bice Curiger named the main project ILLUMInations and started the count of participating artists from Tintoretto.

Fragment of project There is a Beginning in the End… at the Dan Fantin Church. Photo: Natasha Polskaya

In the case of Gary Hill’s video projections, Tintoretto’s light helps expose the construction, the anatomy of the ‘substance of life’ that determine the couplings and joints of the church vaults and arches. And yet it is in the film by Dmitry Krymov that its genuinely magic nature is revealed perfectly. We witness the dismantling of an illusion. Especially created as a stage set, Tintoretto’s Last Supper from the San Trovaso Church is taken apart on film and in real time performance. Stagehands, having arrived at the church with the viewers, end up on the other side of the screen. They take away the cut-outs ‒ reproductions of the characters in the painting. The Saviour comes to life. He takes off his stage costume, picks up a smartphone. It turns out that the leading part was played by actor Anatoly Bely. The camera is turning inside a former factory workshop. An excited woman in a coat crosses the screen. The whole magic appears to be turned inside out, revealing its technical lining. While in the Russian Pavilion a mystical twilight was thrust on us by every available means, here it seems to be dispersed in some sort of humble simplicity. And that is when a miracle takes place. As soon as the illusion turns into mechanics, into machinery, we start to empathise with everything that is going on with unusual intensity. Krymov brought back Tintoretto’s living, spiritual, subtly nuanced light, revealing it in scenes of mundane routine, the everyday order of things. And that is brilliant. It turns out then that great art ‒ right here, in front of us ‒ transforms every moment of our presence here. Whoever has eyes to see, let him see.

Epilogue. Post-truth about paradise on earth

The winner of the 58th Venice Biennale is the Lithuanian Pavilion. And deservedly so. The award was son by the Sun & Sea (Marina) opera-performance (curator Lucia Pietroiusti, music by Lina Lapelyte, libretto by Vaiva Grainytė, staging and set design by Rugilė Barzdžiukaitė). The international jury noted the ‘experimental spirit and unexpected interpretation of national participation’. Basically, the pavilion perfectly embodies the subject of post-truth. A post-apocalyptic theme of a resort is played out in the genre of musical theatre, featuring an excellent score. Ecological catastrophes have robbed people of sun, water and air. The beach paradise is staged in a concrete hangar. And the view from the beach parasol opens to the old Arsenale courtyards where the horizon is obscured by a military submarine like a giant black fish. Each of the ‘sunbathers’ sings his or her individual part ‒ passages about mutations, accidents, depression, desire to procreate in 3D reality. The viewers stand on the balcony above them and watches the beach like some sort of wardens or puppeteers. From time to time, the frolicking children of the beach holidaymakers join them on the mezzanine; however, there is no interaction with the audience. No-one displays any inclination to engage in any theatrics. The pale bodies of many ‘sunbathers’ are far from perfection. The living picture is reminiscent of German expressionism or the magic realism of Balthus. The opera is simultaneously a masterpiece of retro-futurism and an example of the hybrid genre of contemporary theatre stagings in the style of Kirill Serebrennikov, for instance. Another protean image, the truth of which glares in the rays of the scenic sun.