The art exhibition as a conceptual laboratory and a political statement

An interview with Jane A. Sharp, Liisa Kaljula and Anu Allas, the curators of the exhibition Thinking Pictures at Kumu Art Museum

This spring, a long-awaited show at Kumu Art Museum took on an unexpected form, causing controversial reactions. Thinking Pictures, which has been in the making in cooperation with the Zimmerli Art Museum in the United States since 2016 and focuses on dialogue between Baltic and Moscow artists in the 1970s and 1980s – a truly outstanding phenomena in our shared art history – opened on 18 March as an empty hall. There were no works of art, only gray rectangles and labels marking the planned locations of the artworks as well as annotations of thematic sections mapping the conceptual plan of the display. The Thinking Pictures exhibition was supposed to, among other things, bring world-known dissident artists of the Moscow Conceptualist movement together with Soviet Estonian alternative artists, who altogether formed what was known as the Tallinn-Moscow cultural bridge. In broadening the circle of Tallinn-Moscow associates, the Estonian conceptualists were to be supported by Latvian and Lithuanian like-minded artists, thereby strengthening the dimension of Baltic Conceptualism. The exhibition’s three curators – Jane A. Sharp (professor in the Department of Art History at Rutgers University, USA), Anu Allas (Vice Rector for Research at the Estonian Academy of Arts) and Liisa Kaljula (head of the Painting Collection of the Art Museum of Estonia), all PhDs and great specialists in Soviet art history – had made an emphasis on exhibition as research, which had led to great expectations for the outcome of this investigation.

However, the outbreak of the Russian war of aggression in Ukraine caused both museum authorities as well as the curators themselves to revise the format of the exhibition’s display. The exhibition opened on 18 March, as scheduled, but devoid of any artworks – not in denial of the historical dialogue with Russian artists but questioning its possibility at the current moment. This gesture declared the exhibition’s creators’ support for Ukraine, and the exhibition hall stayed like this for one month. Then, step by step, artworks started to appear on the walls – the selection and schedule of installing the works was formed gradually, based on several circumstances. The last group of artworks will be installed on 1 August, and the complete exhibition will be open for two more weeks until its deinstallation on 15 August. However, not all the works from the original exhibition list will be displayed, as there are some images that, since 24 February, we see completely differently now. In summary, from a static object/environment, this exhibition has become a process of thinking and discussion. We are witness to one of those rare moments that has changed the history of the art exhibition as such. Exhibition-making is experiencing a paradigmatic change, one in which the so-called “post-curating” mode focuses on public discourse and discussion instead of just imposing the results of curatorial research. Thinking Pictures became a conceptual laboratory and a political statement – not only during its preparation but also throughout its period of display.

Thinking Pictures. Exhibition view at the Kumu Art Museum. Photo: Paco Ulman

When did the idea of this project emerge, and how did it develop? It was based on an exhibition with a similar concept – Thinking Pictures: Moscow Conceptual Art from the Norton and Nancy Dodge Collection, curated by Jane A. Sharp at the Zimmerli Art Museum (at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, New Jersey, USA) in 2016 – but what are the unique features of this project? Besides broadening its geographic scope, can we talk about the broadening of its core subject – adding, for example, the decolonization or even deprovincialization of Soviet Baltic art?

Jane A. Sharp: When I first developed the concept for the Zimmerli Art Museum in 2016, my goal was essentially to decolonize the presentation of Moscow Conceptualism, which has always been cast as a belated if distinctively Cold-War-inflected derivation of Anglo-American Conceptualism, a dependency encouraged by some of the artists themselves. I sought to explore and bring to the foreground the ironies and ambiguities of its very different visual culture. So, it is particularly rewarding to see the current exhibition take this process much further. I see the show as primarily a presentation of Baltic work, in which the Moscow exponents no longer drive or motivate the narrative but are integrated into a complex web of visual/conceptual strategies and expressive concerns.

Thinking Pictures. Exhibition view at the Kumu Art Museum. Photo: Paco Ulman

Liisa Kaljula: I really hope we take this decolonization process another step further with the Kumu exhibition. And yes, from one side, it is about geographic broadening as this time we are showing conceptual developments in the art that was made in the westernmost republics of the Soviet Union, and especially in their capital cities: Moscow, Tallinn, Riga and Vilnius. And this decentralization aim is also the reason why we try to cultivate the use of the term “Soviet Conceptualism” in the exhibition catalogue rather than using “Moscow Conceptualism”, which is a well-known brand that has consolidated the meaning of conceptual art made in the Soviet Union. But perhaps it’s not only geographic broadening, as the Baltic material brings along with it different approaches to the understanding of the conceptual in the late Soviet context. For example, in Tallinn, Leonhard Lapin and Sirje Runge spoke about the need to create Objective art in the context of a modernized, rationalized and industrialized Soviet society. In Riga, Miervaldis Polis used a hyperrealist painting technique for his sophisticated games of looking at things, and Jānis Borgs – one of the first artists to call himself a Conceptualist in the Soviet Union – imported ideas of Polish Conceptualism to the Baltics.

Anu Allas: In addition to broadening the understanding of Soviet-time conceptual art and creating a dialogue between different regions (and different collections), one of the goals of the exhibition was to work on Baltic regional art history. Over the past decades, Estonian, Latvian and Lithuanian art histories have been predominantly written within national “containers” and framed through references to bigger – often very abstract – entities such as “the West”, “Eastern Europe”, etc. Our question was rather – how can those small art histories illuminate each other while also interacting with something outside of themselves? The first version of Thinking Pictures presented Moscow Conceptualism in such a versatile, fluid and inspiring way that it didn’t impose any strict framework on Baltic material, but rather offered a wide range of connections to explore.

Eugenijus Cukermanas (1935). Prism I. 1976. Tempera. Private collection

Could you say a few words about the history of the Norton and Nancy Dodge collection, which now belongs to the Zimmerli Art Museum? I’ve always wondered about a very practical aspect of the collection – how was it possible to take non-official Soviet art out of the country, a country where practically everyone was closely watched and everything was tightly controlled by the government?

JS: Norton Dodge was an academic who, while on research trips to the USSR in the late 1950s–60s, became convinced that given Soviet excellence in so many fields (music, literature, technology, film), the same must be true for the visual arts – and saw it as his mission to make the rest of the world aware of the extent of the creative innovation he had discovered in underground art. The remarkable thing to me is not so much that he could get the work out – which he did through a combination of means: artists bringing works themselves, use of diplomatic contacts (mail), and official permission by the Ministry of Culture – but that he remained so devoted to representing this art in all its diversity. Our collection of Baltic work is particularly deep and rich – and he was incredibly proud of it.

AA: Jane and many other scholars have done excellent work on the Dodge collection, but there’s still so much to reveal and explore in terms of lesser-known material, the inner dynamic of the collection, stories related to it, etc. It’s usually been understood as a collection of non-conformist art, but in fact, it offers a much broader view on late Soviet art in its complexity. The Dodge collection is also unique because it contains art from all former Soviet republics, a feature rarely found elsewhere.

Leonhard Lapin (1947–2022). Signed Space. From the series Signs. 1978. Oil. Zimmerli Art Museum at Rutgers – Norton and Nancy Dodge Collection of Nonconformist Art from the Soviet Union

Can you say approximately how many items of Estonian and Baltic art are in the Dodge collection? How much of this sub-collection is being shown at Kumu?

JS: The Baltic collection is among the largest groupings in the collection (over 3,000 units), and for Thinking Pictures we deliberately chose some of the major works that have never been seen here (by Leonhard Lapin, Raul Meel, Sirje Runge). What this show has done, for me, is to encourage other approaches, areas of exploration, in drawing works from the Baltic states together – and to move beyond the national identity issues which have perhaps dominated debate over postcolonial representational strategies. But I think we’ll continue to struggle to figure out how we might do this without depoliticizing our narratives.

Raul Meel (1941). Travelling into the Green. 1973–1979. View from exhibition A Vibrant Field – Nature and Landscape in Soviet Nonconformist Art 1970s–1980s at Zimmerli Art Museum, 2017. Photo by Peter M. Jocobs

LK: When we were doing research in New Jersey with Anu in 2016, we were amazed by the amount as well as the quality of the Baltic part of the Dodge collection. The major series by Leonhard Lapin, Raul Meel, Sirje Runge, Janis Borgs and Miervaldis Polis, which is now on view in Tallinn, is only the tip of the iceberg, so to say. But these works were really easy to place in the context of the Thinking Pictures exhibition as their meaning is not limited to their national cultures. Lapin’s painting series Signs, for instance, is an excellent example of Soviet Conceptualism in that it deals with the Soviet sign system – assembling it, examining it, but also trying to infect it with a virus of deconstruction.

Erik Bulatov (1933). Danger. 1972–1973. Oil. Zimmerli Art Museum at Rutgers – Norton and Nancy Dodge Collection of Nonconformist Art from the Soviet Union

How was this display influenced by Russia’s war of aggression in Ukraine, which began approximately a month before your planned opening? This exhibition involves several representatives of Moscow Conceptualism who were like-minded supporters of Estonian artists in the silent resistance during the Soviet era but, at this moment in time, not all of them have unequivocally condemned Russia’s aggression. For me, there is a certain clash between the ethics of being an art historian and the ethics of witnessing of a current political situation that demands our reaction. Yet you developed a great solution here: it is not for nothing that this exhibition has been highlighted as an example of a new paradigm in exhibition making – so-called “post-curating”.

AA: I think it was the first time for all of us to experience that something happening in today’s world shifts the perception of history to such an extent that we can’t not react to that as curators. To look at the situation rationally, the war didn’t change much in terms of the historical material that we had planned to show nor the narrative that it was based on – not to say that this material and narrative had little to do with Putin’s Russia. However, this was the moment when the affective overtook the rational, and we respected it, worked with it, and made it visible. Our whole show was built on the dialogue between Moscow and the Baltics; a few weeks after the war had started and as we were opening the show, it was clear that this dialogue had stopped. There were certain sections of the show that were subtly playing with / subverting Soviet visual imagery (like a big part of stagnation-time culture did) but which could have been misperceived in this state of actual war. Nevertheless, the empty exhibition that we opened was never meant to be a conclusion but a part of the process, and by now we have, step by step, installed most of the works. It had nothing to do with “cancelling” Moscow artists, Russian culture or anything else, but rather with our responsibility as curators to act in a real world rather than in an ivory tower. Post-curating means interfering in an existing exhibition and reworking it; in this case, we interfered in an exhibition that was prepared in our minds but needed to be rethought in this particular moment of time.

LK: I also feel the clash that Elnara mentions because, as an art historian, I could never go as far as to claim that there was no dialogue between Moscow Conceptualists and the Baltic artists during the late Soviet era. The unofficial art spheres in Moscow and the Baltics were equally opposed to the totalitarian state, so there was a lot of friendship and solidarity, as well as creative influences, between these artists back then. However, as an activist-minded curator, I felt that I could not keep working the same way that I did before the war, so this is why we needed to rearrange the whole project from a traditional research exhibition into an experimental anti-war statement. However, we didn’t want to become a repressive organ that praises and punishes, so we decided to keep installing until the very end of the exhibition, treating all the artists the same way but constantly reminding the viewer with empty places that war has not come to an end in our region. I really think the former Eastern Bloc needs to be the consciousness of Europe now, as it is already becoming apparent that the rest of Europe is growing tired of this war and wants to return to a normal way of life. But we also need the help of Eastern European émigré artists in terms of using their position and symbolic capital because it is still much more safer for them to speak up compared to their colleagues currently working in Russia.

Viktor Pivovarov (1937). Do you recognize me? From the series Face. 1975. Gouache. Zimmerli Art Museum at Rutgers – Norton and Nancy Dodge Collection of Nonconformist Art from the Soviet Union

JS: I really like the term “post-curating” because it reminds us that the show was essentially curated, re-curated, and, in fact, continually being curated through the process of dialogue – not only between art objects and real-world events but also among us curators. It’s nearly impossible to imagine an exhibition with no end – a kind of open work – from the institutional perspective. People – art handlers, conservators, etc. – have jobs and need to move on. But in this case, being responsive to the events and moods of the times truly continued to shape the look of the show and its meanings. I have to say, as an American working here during the onset of the war, and even now, I feel very strongly the distinctive series of shock, fear, anger and outrage that is more abstract for those who do not live in the former Soviet-era borderlands. I can only hope that the diverse range of audiences you have here each find something in this show that stimulates, and gives hope. That said, I really wish that the remaining works – by Bulatov, Polis, Mikhailov and others – were allowed to be shown. This final act of a few empty walls remains a cipher – both negative (censorship) and positive (a response to the imagined sensitivities of local viewers).

I imagine you have gotten all sorts of reactions to this exhibition. Are there any worth mentioning, i.e. feedback that was constructive, informative, or that made you rethink your actions?

LK: I have really enjoyed the diversity of opinions around the exhibition because one of the aims of our solution was to induce discussion about the role of culture during the crisis. And the most critical reviews have given me a lot of stimulating thought material, often even more than the positive reviews. But I also liked the Estonian art historian Heie Treier’s comment that in this show, the pieces of the bigger puzzle finally come together. Estonian art during the Soviet era – whether we like it or not – was part of a bigger picture as we shared similar problems with many other small occupied nations of the Soviet Union. However, these comparisons have not really been drawn out after the fall of the Iron Curtain, because Baltic art histories have mainly been written in their national- or Western-oriented frameworks. But in fact, the three Baltic countries shared an almost identical Soviet art system during the 1970s and 1980s, and several theme rooms that we created for the exhibition grew out of this like-minded material. When we built the thematic structure of the exhibition, I was so amazed to see that the Balts actually shared some radical ideas which were specific to the Western periphery of the Soviet Union. For example, the bold imagination of how to intervene and take back their cityscapes using the means of photomontage and different print techniques. This could never happen in the center of the Soviet universe because in Moscow, the public space was so heavily controlled.

AA: As we had borrowed the means for dealing with this situation from the artists we worked with, i.e., turning the exhibition into a conceptual gesture, it was clear that it can be – and has been – understood differently depending on the viewers’ position, experience, etc. It’s not a bad thing, and most of the feedback has been very positive. Probably I’m most glad about some insightful analyses from my students who have no direct experience from the Soviet era but who have now been confronted with it in an unexpected way.

JS: During the months of the exhibition’s installation (March 2022), I was teaching a curatorial training seminar at Rutgers for a group of graduate students. They were absolutely riveted by discussions of process – the dilemma of reaching out to audiences during the war – and we had exciting conversations while being an ocean away. I was so pleased that even these viewers, who could only virtually feel and see the choices we made, understood – and claimed – that this was the best course they’d ever taken at Rutgers. It’s possible to communicate one’s strategies, and their impacts, far beyond the local environment with such a show.

Sirje Runge (1950). Geometry VIII. 1976. Oil. Zimmerli Art Museum at Rutgers – Norton and Nancy Dodge Collection of Nonconformist Art from the Soviet Union

I have a slightly personal question – as curators, you have to treat all the artists and artworks equally, but are there any artists or artworks that are special to you, personally, at this exhibition?

JS: For me, this is such a difficult question since I know all of the “Moscow” artists (most of whom now live elsewhere in Europe), and I’ve only recently met or had contact with the Baltic artists; among these, Sirje Runge’s works mean a great deal personally, as do Raul Meel’s. The great discoveries for me are in the artist group Pollutionists and other sections of “Interventions in the City”. I’m extremely grateful to Liisa and Anu for their extraordinary efforts to research and locate so many works in Riga and Vilnius that are new for me in this exhibition. It is also wonderful to see some of the familiar Moscow classics presented within the context of entirely new narratives: Nakhova, Kabakov, Albert, Zakharov, Monastyrsky.

LK: My personal favorites are the two series by Latvian artist Miervaldis Polis that are scattered around different collections in Europe and the United States but finally had a chance to come together for this exhibition. Colossus Island is a work that imagines the artist together with his wife, Līga Purmale, discovering a lost civilization, Colossus Island, with gigantic finger monuments. It is such a great metaphor for Soviet society, treating the finger as the symbol of totalitarianism, but also a good example of how Soviet conceptualism used serial medium and storytelling, which were not only characteristic to Moscow Conceptualism as we tend to think. While the Polis in Venice series is a marvellous appropriation of a Venice travel guide and an escapist fantasy by an artist who had never been to Venice.

Ilya Kabakov (1933). The Short Man (The Bookbinder). From the series Ten Characters. 1980–1987. Exhibition view. Collage, ink, coloured pencil and lithograph. Zimmerli Art Museum at Rutgers – Norton and Nancy Dodge Collection of Nonconformist Art from the Soviet Union

AA: Conceptual art has been known as a rather masculine, even chauvinist phenomenon that has often left out or side-lined many women artists who were actually very much participating in the movement. We tried to balance this as much as possible, so all women artists at the exhibition are particularly important to me – not only because of their gender, but because they often broaden the strategic horizon of conceptual art. Like Jane, I’m fascinated by the Pollutionists, but also by some other photo works from Baltic artists like Mindaugas Navakas, Violeta Bubelytė, etc.

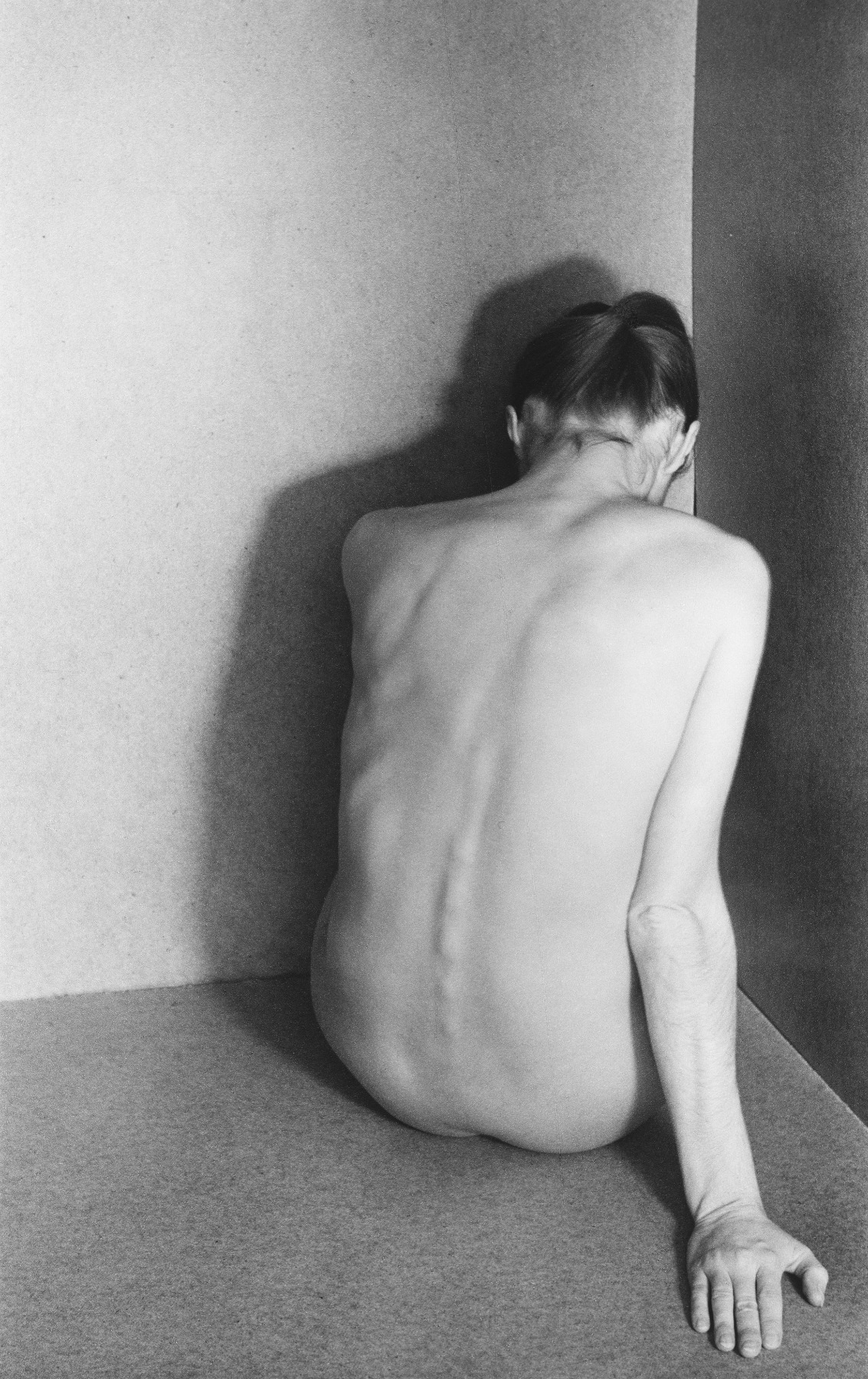

Violeta Bubelytė (1956). Nude no. 23. 1983. Gelatin silver print. Lithuanian National Museum of Art

Is there a plan to show this exhibition in other venues? We have here an integrated and evocative whole that has great potential as a traveling exhibition, at least in the Baltics. Do you already have some ideas on how to develop this project further?

LK: This show was actually meant to be a traveling show because the five-year-long preparation of the exhibition has meant a lot of work for many people, and bringing works from the United States these days has become very expensive. And since the art world is moving towards a more sustainable mode of operation, we were negotiating with several Eastern and Central European museums before the crisis regarding second and third venues for the exhibition after Kumu. But now everything has, of course, been cancelled due to Covid and war, and the works are traveling back to the United States and the respective Baltic collections after the show closes on 14 August. However, our focus at Kumu Art Museum for the next few years is to work with Baltic culture connections, so who knows, perhaps the Baltic part of the exhibition will become a traveling exhibition at some point.

Mindaugas Navakas (1952). From the series Vilnius Notebook I. I–XII. 1988. Zincograph. Lithuanian National Museum of Art

JS: Although it is disappointing not to see the exhibition travel within Europe, I’m looking forward to taking advantage of all the advance conservation and preparation we did for the Baltic works, and plan to install many of them (many by women artists) again shortly in our main galleries, to continue rethinking the histories that emerge from this era.

Thinking Pictures. Exhibition view at the Kumu Art Museum. Photo: Paco Ulman