Two Brants

27/07/2012

I meet with Harijs Brants before the opening of the exhibition featuring his sketches, scheduled for July 27 at the Cēsis Art Festival. During our conversation, Harijs leafs through the many pages covered in drawings and, at times, illustrates his point with one or two of them. However, it is his large-format charcoal drawings that have been reproduced the most often; they are much more involved, although in terms of theme – mellower. I attempt to get to the bottom of these differences.

Harijs: I have a feeling that drawing like this [sketching] has come to an end for me.

Vilnis: You mean fantasy pictures?

I call it a dumping ground for fantasy. I even tried finding key words with which to formulate it, and I wrote down all sorts of silly things.

For instance?

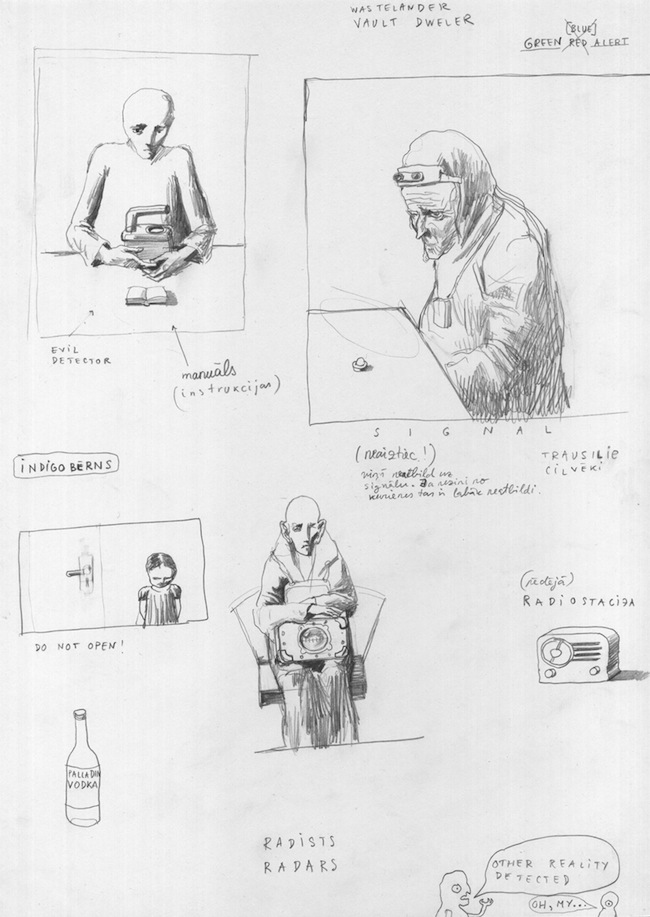

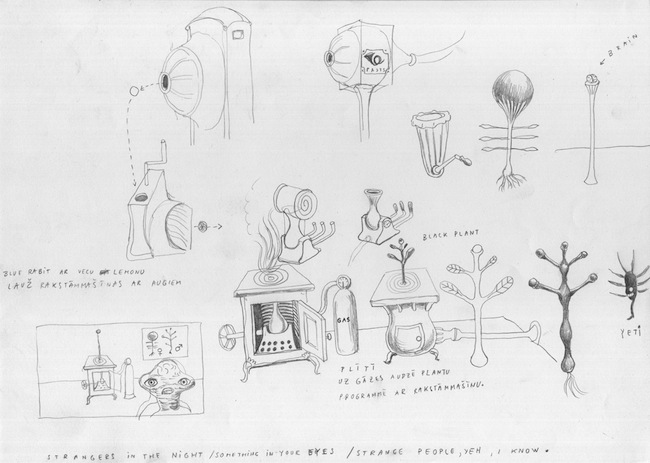

The mind in reverse. I read about the surrealists. What did they manage to pull out? Everything that's in the unconscious. The more paradoxically that things are connected, and the more that their meaning is changed, the better. Because it's more unrelated. See, it's quite a task. But the more I'd think about it, the more I started to not like this surrealism. Even though, if going by what's in the sketches, I should count myself as one of them [the surrealists], because there's a different function here. [Leafs through the sketches.] For instance, the Geiger counter here is a detector of evil. I should have given it that meaning. The person has it in his hands; I should have made the viewer think about it having some connection to evil. Maybe this is an interpretation, not quite surrealism...

I was interested in it all the time, but now... I think, if I continued to do this, it would be serving its own ends – it would be keeping something going that used to happen naturally.

Is it not coming to you anymore, or does it seem as if there's no point in putting it on paper?

It still comes. If I shake the “box”, stuff still comes out. But, if I get the idea that it should be drawn permanently, with coal... There's a technical problem as well. I still haven't been able to put a lot of things into one drawing. For instance, if the sketch has ten elements, then to put thirty in the drawing – so that they interact among each other on their own, and a process occurs, about which I don't really know what it is. It would be pure aesthetic enjoyment – it looks good, it has a good vibe. Unknown objects, well shaded, would make it seem as if there's some sort of world there. An aesthetic high, like it is with people who are really into antique things. For instance, transforming a 1920's lamp into something else – you don't know yourself what it is, and wonder at it. But now it seems as if its just another kind of burden; that instead of messing and fooling around, I'd like to understand more. That's why the portraits that I draw are an attempt at understanding. I don't know how much it is possible for a person to understand: Who is he? A drawing is an attempt to look into a person in a different way – not with the help of text, but with his visual image. A drawing is an attempt to either reflect, or to find something else, draw something out. So you see: all portraits have swept surrealism away. I've always had a dream to make a work that would be more like sketches. Make a work characteristic of surrealism. But I've always put that off, again and again. With coal, you can make two or three things, but if there are many, and they're small, then you'd have to sharpen the charcoal much too often. That's why in big works, there is one portrait, one wall; and that's tiring enough.

Would you get tired of drawings with many objects?

I would tire of them, yes. A person, a portrait – that's a serious goal that ensures an everlasting... what? It's disgusting overall, trying to describe with words that, which is being drawn. And the craziest thing is that today, I can tense up and try to explain something. But I am sure that after a year, I will be able to deny it all. That's why – is there any meaning in the part that is told? Does it even carry any weight?

There is – there's educational meaning.

You have 1000 sketches. How can you tell which ones could have the potential to be turned into a large drawing?

I have a feeling that there are so many because I'm really having a trying time. I used to not have a single drawing, just sketches. They were accumulating, and all just in A4 size. Now it's completely different. There are barely any sketches. There are just compositions – a person, half of a figure without arms, a portrait...

There aren't any sketches for the portraits?

No. Just for the one, which was said to look like Gints Gabrāns, even though the eyes were taken from the actor Tim Roth. I thought – I need one with a narrow arm... Hey, he looks a bit like you! I thought – I should really try and draw a portrait by myself, from heart [Harijs usually works with previously selected and mounted photographs – V.V.], and – yes, it came out just it should have – a bit “old-masterish”, posed at a three-quarter's turn. Then I cut out details from other pictures on the computer, and tried to put these details into the drawing. Well, I really taxed myself, but at the end, it ended up as my piece called “Behind the Wall”. Actually, those compositions that are in the sketches never get anywhere.

%201020%20x%20610%20mm-Charcoal%20on%20Paper.jpg)

The Candy Eater. 102 x 61 cm. Coal on paper. 2012

I look at your sketches as if they were finished works, because they don't need anything else. The themes are comprehensible, and the shapes – laconic. The only problem – how can you bring it to the viewer? The sketches are very small.

There are several drawings on every page of A4. There was the idea – maybe they should have been made large-format from the start. But there's a problem – to make a drawing the way that I do now, I have to know how dark every space will be beforehand. If I haven't planned for it, and if I have to erase a bit, I can no longer get that spot the exact shade of gray that I need. Right away, the gradient of darkness jumps to +/- 20%. The tonality is very unstable. It's hard to reign in paper that has been roughed-up.

Then why do you draw your large-format works so finished?

I want to attain a believability that the drawing can become palpable. I want the drawing to approach the level of a photograph. But they're not photographic [the images], because there are a lot of things that are wrong. The shadows aren't right, the...

The Watcher. 102 x 58 cm. Coal on paper. 2012

We don't notice that.

Yes, its trickery. Drawing has the advantage of trickery – adapting a necessary shadow or shape. A photographer can't do that. A photographer has to get the lighting right, and the image is just one take. But when drawing, you can change the lighting, the angles and the proportions all the time. You can put the nose in a bit of a different angle, bring the eye out – according to need. In order to bring out the character, you can act freely, even if the image is realistic. Combining everything in terms of tonality and rhythm, believability arises. Although – if someone could make him (the person I have drawn) three-dimensional, it would be a really deformed human being. Not at all as good-looking as he looks in the drawing. Because as it turns out, character – expression, is what shows up in the drawing; but you can't say that about the person who was drawn.

But why couldn't you draw these sketches larger? Just the same way – using lines, but just, say – three times bigger? We can also understand images that aren't photographic.

When I used to draw caricatures – grotesque figures with pumped-up heads... I had a period when I was powerfully influenced by computer games – but that's old news. Cartoon characters have always interested me, which is why I've always drawn all sorts of comic figures. On the way to realism – although I never projected that I'd be making drawings as realistic as the ones I do now – at one point, there was a transition period: little girls with disproportionately large foreheads. I slid out of that stage somehow. But what was it that didn't satisfy me? Probably the fact that it wasn't really believable. That the image itself places boundaries. In the sense that it very strictly dictates what we see. When we can no longer interpret what is seen in the abstract – in the geometric cacophony. I have a tendency to deliver a concrete feeling to the viewer – that's an objection. But I haven't specially researched this myself. I just know that at some point, it became much more interesting to me.

In the sketch, we see, for example, a wrinkled old man sitting at a table; in front of him is a cup full of brains. An alien is sitting next to him. I won't ask about the story being told. A large picture could also be drawn with a line, a shadow hatched-in, and so on. Preserving the movements of the hand, which you completely remove in the finished work.

Ahh, to preserve that carelessness? I like to joke that to draw like me, you don't need any skill. It's very simple – If I don't draw for a year, the only thing I've lost is the ability to concentrate for long periods of time. And my fingers hurt if they're not used to it; I must have a thin palm. The whole of my assignment is to solve the relationship of “darker – lighter”, which I must do in any way possible. With a brush, by rubbing, scraping – it doesn't matter. I can poke with an eraser, make dots with a pencil. Any trick will do. There is not a single streak nor line – they must not show up in my work! If there is one somewhere, than that's a flaw. A line achieves concreteness; it has been visibly drawn. But that can't be! I've thought about how our sense of sight is ruined by the possibility of looking through a viewfinder, how it changes the conditions of perspective and everything else. But that's another story. A careless drawing wouldn't be interesting to me, because I probably need shadows and light; that the light is coming from somewhere. Although, I could make a drawing in which the sky is overcast. And I also want a lot of space.

How do you select the sketches to be exhibited?

For example [shows a sketch] – could this be called relatively good? This next one, for instance, is better. If there are three, then they form a composition that can be exhibited. And so on. There are, of course, duds!

You're known for your large works. They're mostly portraits – only at the very beginning did you draw something similar to skeletons. Could it be that you are assumed to be a portraitist, while the weirder, more surrealistic ideas are destined to stay as sketches?

Those portraits watch me. See, there's a psychologically therapeutic motif as well – maybe they're treating me? [Laughs] Something happened recently – I had been sketching all day. The good thing was that some sort of inner pressure had formed in me. Like in a pressure cooker, when a ventilation hole has to be opened to relieve the pressure. By working the whole day, the ventilation effect had worked. But on the other hand, I didn't feel well from that which was coming out. Instead of making happiness and surprise, it was depressing. Because in many of these ideas, there is something quite disconnected, in a bad sense. Chaos manifests there. I don't think that it's natural for a person to wish for chaos. Nevertheless, I think that fantasy is something of itself – with its intensity; I can't ignore it. But it is quite chaotic. You can work with it in several ways: it can be used, you can try to tame it, organize it, review it and put it into works with content. If the potential – the event – of chaos can be so used, then in my opinion, that's very good. But you can do it differently: be less controlling. Let it do its own thing. But then, when I've caught myself doing that, depression arises.

Once, after you had done the cartoon drawings for the show “Ice”, and I asked you about the role of erotica in your art, you distanced yourself from this topic because it wasn't relevant anymore. Now, when I show interest in the surrealistic and fantasy elements in your drawings, you distance yourself from these as well.

There is one way in which I can try to speak about that – by using a description of the process, how I approach a drawing, how I try to start. It's quite awful, in a sense, because the amount of material that is created during the process is so large and encompassing that it's very difficult to choose. Very often, two very similar characters compete with one another. Every character has sub-characters. As soon as I allow myself to look for them, they begin to multiply faster than I can sort through them – which is the best, which isn't. And they change even on a daily basis. Then I fall into a sort of labyrinth, and I have only one wish – to quickly get out of this situation and to focus on only one task, and bring that to a finish. These sketches give proof to the amount of work that I haven't been able to finish to any sort of degree. I could say that the sketches are good enough by themselves, and that that's just the way I draw; but then I, as a perfectionist, would have given up on my wish to bring something to a conclusion that would surprise me, as well. The surprise that I create for myself – by drawing an eye with expression, or in the details, or in a corner of the mouth – is much greater.