Who should we be afraid of…?

Sergej Timofejev

…artificial intelligence or ourselves? A conversation with Lev Manovich, Professor of Computer Science and author of ‘Cultural Analytics’ and ‘The Language of New Media’

‘There are 20 million programmers, 20 million designers in the world, and the question is ‒ even if a masterpiece were to be born, how would we notice it? For more than 13 years, my laboratory has been looking for a solution to the problem of observing culture, seeing important things, noticing trends in this era of unprecedented scape,’ says Lev Manovich, Professor of Computer Science at the City University of New York. In 2007, Lev Manovich created his Software Studies Initiative research lab, which became the first centre for computer analysis of big data in culture ‒ all these constantly escalating massive amounts of images and videos published in the digital environment.

In 2016, this initiative was renamed the Laboratory of Cultural Analytics, and in October 2020, Lev Manovich’s ‘Cultural Analytics’ was published ‒ a book that is a summary of this part of his research and this period in his life. One of his previous books, ‘The Language of New Media’, became a genuine cultural bestseller; it has been translated, among other languages, into Russian and Latvian, and this year saw the publication of the Chinese edition. The book also sums up a whole period of interests and studies in Manovich’s life – he has been teaching media art since 1992, and has frequently appeared in various conferences and programmes.

We contacted Lev in early November, when activities such as travelling had again become temporarily impossible. The US elections were still ahead, and there were concerns of potential civil unrest in connection with that, while in Latvia, vast passionate debates were taking place on the necessity of wearing face masks in public places. A good acquaintance of mine, a professor of economics, had recently reposted on her Facebook page a news report which said that the pandemic was almost completely under control in China, very obviously hinting that something was being concealed from us. Contrastingly, Lev had just forwarded me a link to covid19.healthdata.org, where there were charts developed by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), an independent research centre at the University of Washington, that modeled the spread of the pandemic. In these computerised charts created by ‘smart machines’, universal mask wearing and the complete suspension of various public events were the key criteria causing infection rates to radically change. On the following day, Lev and I got together on Zoom. It was 10 am in Riga but already 5 pm in South Korea, where Lev joined me from his home ‘studio’ for video conferences. We opened the conversation with the selfsame Covid modelling charts.

…Those people at University of Washington, they are not idiots. They demonstrate in their charts that if everybody is wearing masks and periodically everything is shut down, the infection rate remains approximately the same. Of course, this is not ever going to happen. And that is why the numbers will be growing practically everywhere.

This situation is currently also discussed as a kind of endurance or reliability test for human social systems. Why is it that Asian countries seem to be coping better at the moment, whereas Europeans are re-entering a period of total lockdowns again?

My wife is from Korea, and we have been staying in South Korea since late March. It has been a sort of immersion into Korean society. And for me, Asia has already entered a new age completely. They have overtaken us on so many counts. It may not at all have been obvious to everybody, and perhaps it still isn’t obvious to everybody. Nevertheless, thanks to their ways of coping with coronavirus, it has been gradually starting to dawn on many people that Asia is already living in a somewhat different dimension. First, everybody wears a mask, except while visiting a café or a restaurant. The culture of the body is generally on a high level here: everybody is washing their hands all the time. And when the SARS virus emerged, they developed a very sophisticated system of fighting with similar things; it comprises various different elements, including contact tracing. Furthermore, they closed their borders at the right time and, while separate hotbeds still continue to appear occasionally (in Korea they mostly have to do with church communities), they are able to control them.

Whereas in America, no contact tracing system will ever work. They are not prepared to implement them because people do not trust their government. In Korea, if they call you and tell you that you have tested positive, and please help us contact the persons you may have interacted with over the last 5‒15 days, people, on average, submit 18 names. In America, half of the people simply hang up on you and the other half give just one or two names. People are afraid. In the Baltic countries, which are quite small, contact tracing ‒ on principle ‒ should work ideally. The population of Korea is 50 million, after all.

Still, there must be a different type of mentality involved in this. It is universally accepted that everybody is different, and yet together, we are all a single interconnected society. The individual and the communal seem to be balanced differently.

Absolutely. In terms of infrastructure and aestheticism of everyday life, the developed Asia is some 15 years ahead of us. On the other hand, they have retained this sense of collectivism. Family is of extreme significance here; one’s relatives and relationships with people in general are very important. People think of others first, only then ‒ of taking care of themselves. When someone is parking their car, they fold their side mirrors automatically to leave a little more space for the person who will be parking their car next. And when I forget to do that, my wife always reminds me. It seems to be a little thing, a trifle. And yet these little things accumulate and shape the general picture.

How do they treat conspiracy theories and fake news in these countries?

I do not have exact data regarding this, but my intuition tells me that all these rumours and news reports based on them are evidence that people do not trust their government. And that is why they are looking for conspiracies on every step. Here, in Korea, democracy is in a quite robust state: people are reasonably active; there are protests and pickets on a variety of subjects going on every Saturday. Four years ago, as a result of similar protests, the corrupt president of the country, Park Geun-hye, resigned from her post. Meanwhile, people really have greater trust in the political system on the whole, and when people trust each other and trust the system, they have no need for fake news or rumours. They are quite satisfied with the official version of political events. Whereas, say, in Russia ‒ or so I have read ‒ not so long ago, as many as 50 % of the population did not believe in the existence of the coronavirus. I mean, there is this link between these things.

And yet this sense of everything not being ‘quite right’, not moving ‘in the right direction’ ‒ it is a wide-spread thing in the West on the whole. And this total lack of trust somehow also turns against the new technologies. They are also viewed with enormous suspicion.

There is a sense of a crisis, and it is connected, of course, with more than just the coronavirus. It is also a political crisis, all this giant wave of populism. Since I have started taking an interest in Big Data, I have, of course, fallen in love with statistics and various surveys. So I recently read a survey where young people were asked: in your opinion, is your generation going to live a better life in terms of prosperity than your parents? In Africa, 95 % said ‘yes’. Or let’s take China, where a third of the population transformed from the poor into the middle class in a mere 15 years. They are not experiencing any crisis; they feel extremely optimistic. And the situation is similar in many developing countries. Whereas Americans and Europeans ‒ 70 % of them said ‘no’. There was this ‘golden age’, relatively speaking, in Europe and USA between 1955 and 2005, when life was visibly improving in front of people’s eyes. The situation changed ‒ for a variety of reasons. For instance, the population of Europe aged: the average age is approximately 44; in Asia it is 30. And that is why they are more open to change, to everything that is new.

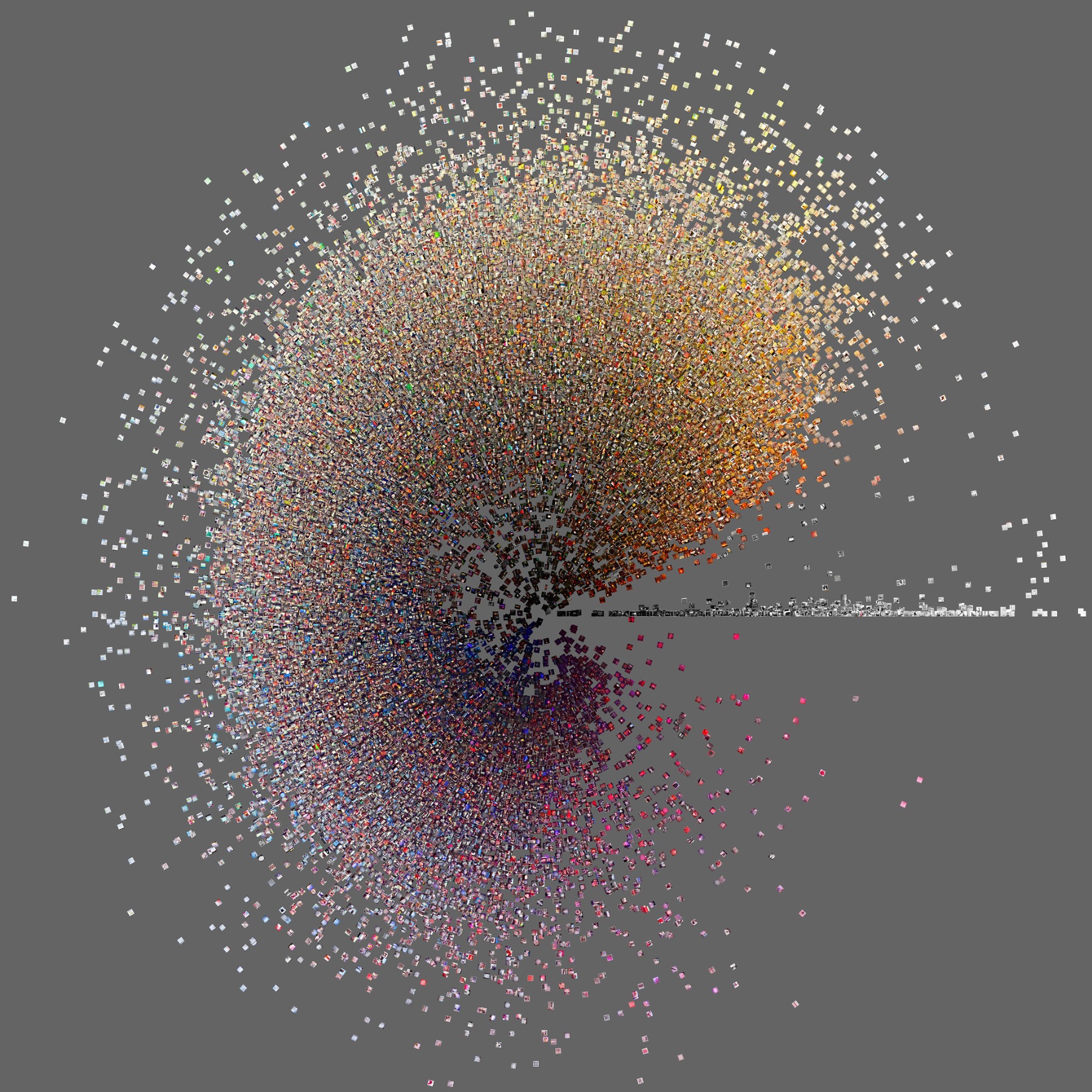

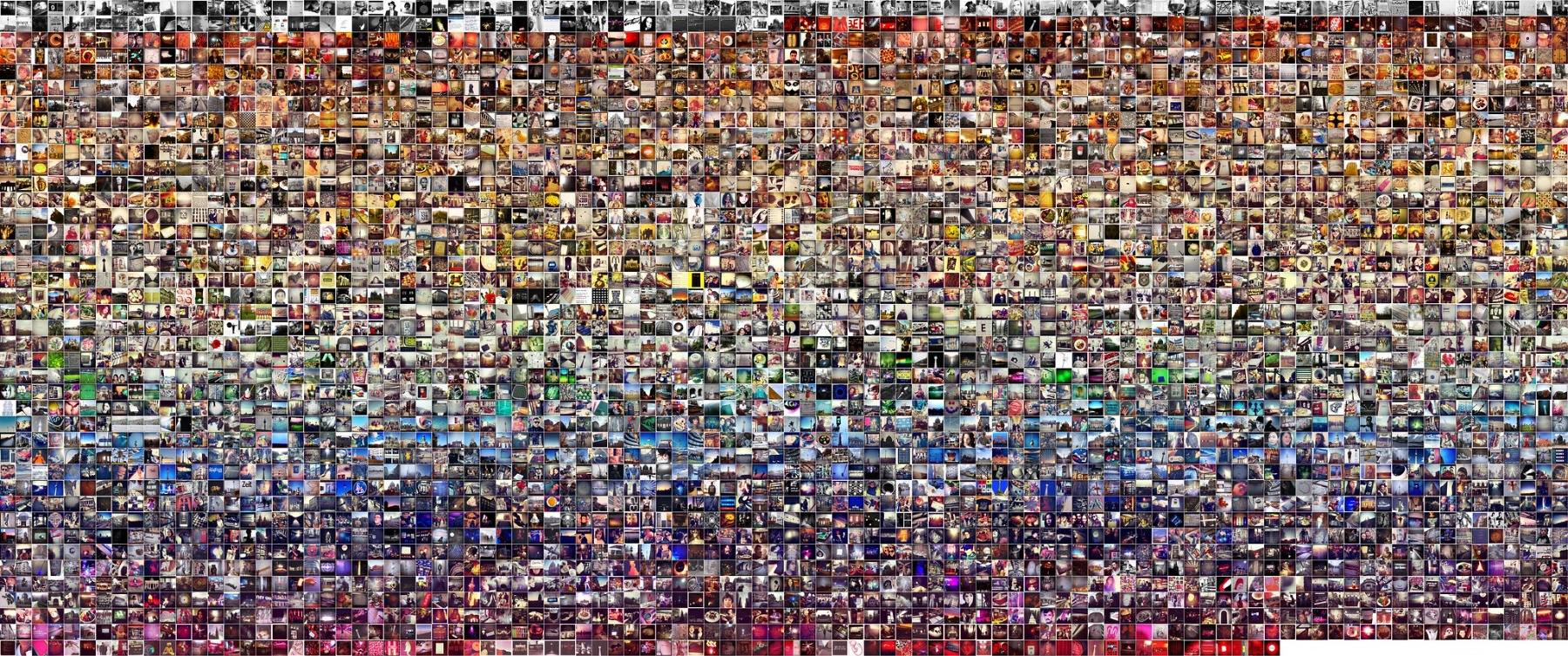

From the project Phototrails. High resolution visualizations created with custom software using 2.3 million Instagram photos from 13 global cities

Is there also a noticeable difference in trusting Big Data?

The modern Western society was formed as a result of two revolutions ‒ the French Revolution and the American one. It is based on universal values like liberty, equality, freedom of speech and privacy. For this reason, there is this great mistrust of anybody collecting data – be it Google or the government. ‘This is my private world, and I am not letting anybody in!’ As someone with a global experience of living between Asia and the West, I personally feel that this particular outlook is somewhat dated. I absolutely don’t care who is following me and collecting my data. Whenever I use various services or applications for the first time, I always say ‘yes’ to all these questions about cookies. I even find it intriguing that all this amount of data is being stored somewhere. The question is ‒ how this data will later be used. To what extent is the system of law and justice capable of protecting you from being persecuted for an e-mail or a tweet, as it occasionally tends to happen in Russia.

Or let us take contact tracing: South Korea has a very democratic society of high political culture. But when people are asked here ‒ how do you feel about a situation where we will be tracing your phones, your credit cards ‒ they say: yes, we understand the risk and we are not very happy about it, but it absolutely makes sense if we can beat the coronavirus this way. People are generally very advanced here; they understand what is happening and they trust their government, which, in this particular situation, is temporarily given the right to exercise this level of control over the population.

But why is there such a different level of acceptance/intolerance? Is Korean society in general more oriented to efficiency of certain decisions?

It is, of course, my interpretation only. But I feel that it is a more contemporary, more elastic approach. For a country to develop, people need to be elastic. Europe and America have this fixation with certain values that were born in the 18th century, and they don’t want to change them. People in Asia are more open to a changing situation.

Another area where we encounter big data and algorithm control is social networks ‒ how we build our own circle of information and how we obtain information in general. Many people are worried that algorithms are starting to restrict their life, making it narrower. To what extent are these worries valid?

Back in 2011, Eli Pariser published his ‘Filter Bubble’, which described this very situation. We used to have a TV, and we used to watch whatever was on. And there was a kind of consensus among the population. In the USSR, all the TV channels lied, but they all lied in the same way. In America, there was a difference between various sources of information, between the New York Times and The Los Angeles Times. However, back then, journalists really checked their information and they strove toward some kind of objectivity ‒ as it was understood then in the press circles. So the news reports were approximately the same everywhere. Of course, even back then there were people who did not believe anything they were told, but they were few and far between. And then the Internet came, and 20 years later a completely logical thing takes place: you can subscribe to a variety of channels, but you choose the ones that fit your own picture of the world. Which is completely understandable.

Meanwhile, I also read about a special app created by some artists; it subscribes you to a special selection of various conservative channels to expand your picture of events around you. However ‒ suppose this selection includes, say, the TV programme ‘Sunday Evening with Vladimir Solovyov’ on the Rossiya channel: you will only be able to manage the first five seconds, and then you will be consumed by sheer revulsion. It is very difficult to force people watch channels that do not match their own picture of the world. And I think the algorithm is not at fault here. It is the consequences of this new alternative reality where thousands and thousands of channels are on offer.

At the same time, there is a nongovernmental organisation with a team of researchers who rate various media according to their level of bias, either left or right, and their level of verifying their information and whether they strive to provide objective information or appeal to your emotions. The New York Times does not have the highest score in this respect, because they are focusing strictly on New York, they are very liberal (which is why they could not understand for a very long time why Trump won the 2016 elections), and their columns are also very emotional. It turned out that the most objective channel of information was a newspaper to which I already had a subscription, because I intuitively felt that was the case. It’s The Financial Times. Because if you work in business and you buy stocks and shares, you really need an objective picture of the world instead of biased opinions.

By which I mean that we, of course, can blame artificial intelligence for everything, but the reality is ‒ various problems have their own causes.

But perhaps this situation and the influence of AI on our choice of information still does polarise the world, making the red redder and the green ‒ greener? The situation with the US elections and the radical polarisation of views in American society are a strong example of that.

Yes, polarisation of the society has taken place. Ten years ago, if you attended a talk, there would definitely be some incisive questions from the audience; today, you are more likely to hear applause. This circle of people attend this kind of talks and that one ‒ another kind. It is almost like Communist party assemblies in the Soviet Union.

There are many reasons for this kind of polarisation, but I don’t think it has anything to do with AI and algorithms. Those are giant systems, neural networks that make billions of decisions every day. Even if you are researching something, you cannot cover the whole system. And there are countless articles on the subject of ‘filter bubbles’, half of which say that yes, it happens, and algorithms are to blame, and the other half say ‒ no, not at all. Which is also quite typical for certain contemporary global matters in general ‒ you can find a number of arguments confirming one answer and approximately the same number attesting to the opposite.

How has your research of big data and cultural analytics progressed over the last five years?

It has resulted in a book that was published a couple of weeks ago by MIT Press ‒ ‘Cultural Analytics’. I do, of course, worry about it ‒ not so much about the number of copies sold, but I do want it to be noticed; I want people to hear about it. I have dedicated 15 years to this subject, and the book is a summary of everything I know, or, to be precise, have managed to learn by a certain point in time. Because the process of preparing an academic publication is a somewhat lengthy one, but the world is not standing still. But I hope the book can become a kind of manual on this subject of how we should deal with these millions of images and this enormous mass of contemporary digital culture ‒ how to view it in general.

Alongside that, I have lately been working on a project called Elsewhere. The idea of looking at the intellectual map of the world and observing its ways of changing seems very appealing to me. The idea behind the project came to me in 2015 as I was walking down Miera iela in Riga with an acquaintance; it was declared a ‘hipster street’ at the time. And I said to him: why am I researching websites like Deviant Art and Instagram ‒ why should it be digital things only? So many hipster neighbourhoods, shops, cafés and co-working spaces have appeared in the world lately; so many conferences and concerts take place. Why don’t I study culture through actual physical cultural events? Because since globalisation, the number of cultural events and the number of their types have also grown many, many times. And now it’s five years later; we have compiled the data, and I am writing a paper. To date, we have compiled 4.3 million events in 200 countries between 2003 and 2019. But it is not just the temporal and geographical coordinates that we are compiling but also their descriptions. For instance, an exhibition opens at a museum, and the curator writes a few words regarding this event. If you have millions of these texts in your possession, you can, on the level of words, phrases and keywords, trace various terms – how they emerge and how they migrate. Do they make an appearance in the big cities first, and then spill over to smaller ones? Do they migrate from the West to the East, or along some other route? We have built a data base that allows tracing the route of ideas through the world. Through 22 thousand cities. And for me it is important ‒ getting to know what is happening beyond the traditional centres. What is happening in Vyshny Volochyok? What is happening in Klaipėda? Hence the title of the project ‒ Elsewhere.

Does this project allow for the making of certain predictions?

I think it does. If your dots are all situated along a certain line, you can extend the line. And one of the things you can try predicting is the potential impact of the coronavirus on the development of culture. I should mention here that our data also cover the years 2008 and 2009, when, despite the economic crisis, there was no decline in the cultural sphere. Everything continued to grow.

In one of your interviews – I think it was in 2017, and it was also on the subject of AI – you mentioned that the shortest way is not necessarily also the most needed and interesting one for people…

I speak about this quite often ‒ about the fact that our society is still following the same old ideals of the industrial era, which is efficiency and rationalisation. And these ideals have penetrated every area. In many contemporary fields, you are transformed into a worker, spurring on your own efficiency. And the fact that you can also use various gadgets for that only pours more oil onto the fire. A single criterion is applied in all these smart-cities, smart-everythings. It is rationalisation, economy of our time, economy of resources. A very engineer-like approach.

But that is not the way a human is built. Imagine having the same thing for breakfast for the rest of your life ‒ something very good for you and inexpensive at that. You would still rebel! That is exactly why we live in big cities ‒ because all sorts of unexpected things may happen there. You attend an event and bump into an acquaintance; you go for a drink with them ‒ who knows what can happen next. At the same time, the more people are able to measure things, the more they attempt to rationalise everything. And, as I and my students agreed recently, the coronavirus era has only intensified this trend. In the past, you could go loafing about the city, and things would happen to you. Whereas now you are staying at home and ordering the whole city to be delivered to your doorstep ‒ pizzas, all kinds of products, books and so on. And so it is getting harder and harder to do something absolutely random or unexpected.

Perhaps that’s also a new area of data for AI ‒ constant factoring in of this element of irrationality…

How do we appreciate irrationality or, rather, how do we build everything to consider not just the criteria of rationality…

In this sense, it would perhaps somewhat calm down this fear of being controlled by AI if the AI itself would base its decisions not just on rationality alone…

Yes, definitely. At that, deep learning and neural networks are now being employed everywhere, at every step. For instance, Google search ‒ it used to be algorithms, now it’s AI. The whole thing looks the same, it’s just that the actual search has become so much more efficient. But if we look at machine learning from a more philosophical angle, on the one hand, it may be completely customised to fit you. It looks, for example, at what you are reading and listening to and starts to suggest things especially for you. In itself, it is an absolutely positive thing. But alongside that, in millions of cases a different approach is used, when it’s not your data specifically but data from millions of people that is fed into the system. And the neural network establishes certain patterns that are basically a kind of arithmetic mean. This approach is not without its problems; certain things will be simply cut off. So a kind of average universal subject emerges here. For instance, the software that applies various filters to people’s pictures according to its own automatic settings is oriented toward the ideal of an average ‘perfect photograph’.

In your opinion, will this element of averaging out, copying everything, continue to grow, or will AI learn to balance itself and incorporate an element of ‘mistake’, of surprise?

Computer science is an enormous field, and there are countless people working in it. It has a sub-sector that is recommendation systems. This has been a huge subject for many years now ‒ how do we find the right balance between showing people things they have liked before and introducing them to something new. And there are certain solutions to these problems.

Although there is not really a great wealth of data on this subject. Last year Spotify published a report saying that the musical taste of its average user has considerably widened over the course of two years. Meaning that their recommendations have facilitated that. But it is just information released by the company itself. There are very few independent studies on this subject because the data is in the hands of the companies. In any case, it all depends on what kind of solutions, what kind of algorithms are used by the company. Everything can change depending on the choice.

Of course, diversity of culture is a very important subject. One of the objectives of my big data study was creating some kind of metrics for measuring diversity in culture. There are certain methods available, it’s just that I need funding; I need a team for that ‒ I cannot do everything on my own. For instance, we could have compiled several millions of photographs on Instagram and analysed the aesthetics, the subjects and so on, to see whether they are becoming more diverse over time ‒ or not.

I came up with ‘cultural analytics’ back in 2005 because it seemed to me that there is such an abundance of cultural objects that it would be useless to simply sit down with a cup of coffee and have a good think. And I managed to achieve certain things, but so much more was left outside of my reach purely due to practicalities.

From the project Phototrails

And yet, coming back to predictions ‒ how do you see the model of interaction between man and various systems based on artificial intelligence? Is it a ‘master-slave’ relationship or symbiosis, or is it just the opposite ‒ will AI manage to stimulate the growth of humanity as a species, as a community… What is your take on that?

We must distinguish between the ways in which AI is integrated into all kinds of user services and ways in which it is employed in industry and science. Although in both cases, in our race to achieve greater efficiency, we are transferring more and more processes to neural networks. At that, people who use them frequently do not have a clue how the whole thing works. In science, this kind of model is of very little use. That is why I believe that people will gradually start using increasingly ‘transparent’ networks. There is a kind of battle going on around this: which is more important ‒ efficiency or transparency? If I were, so to speak, the President of the World, I would say: ‘You know, guys, it’s not like everything in the world really has to be efficient. But what we do need is knowledge of how these decisions are made.’ I think that transparency will become increasingly topical.

Another story ‒ Bruno Latour, the first 21st-century philosopher who invented the actor-network theory. It means that we are gradually starting to view non-human agents as someone who has rights. I am sure there will be lawyers whose speciality will be the rights of AI ‒ for instance, did an accident take place and who was the culprit? The operator, the machine, the company? This area will definitely develop. And there will definitely emerge a new area of social sciences and human studies that will focus on relationships with this kind of non-human agent.

As we watch all this, we are wondering ‒ how fast is the world changing? Which are the periods in the history of mankind when the most intense changes were taking place? Was it from 1905 through the 1930s? Or was it in the 18th century? It seems to us that it was in our time. But perhaps that is an illusion? From this point of view, it would be interesting to see what happens in 10‒20 years’ time to be able to say: things are going to change radically in this area, while this area will stay the same. Just think of all the things that have taken place in just a year’s time. For instance, the whole fashion industry has changed. More and more designers are giving up the traditional fashion weeks, the race to make new collections all the time. And I have this feeling that there are a handful of subjects that will become very important in as little as five or ten years.

Do they have anything to do with our evolution and development as a species, as a community?

I think when we look at the social sciences, there has not been much progress since the times of Aristotle ‒ he already defined comedy and tragedy. Or perhaps we should start with Buddhism. In any case, a couple of millennia is a very short time for our biology to undergo any significant change. On the other hand, there is such a thing as cultural evolution. From the moment when man invents language, he starts to evolve culturally. Then he invents instruments, fire and so on and so forth ‒ all the way to self-operating machines. In other words, it is the very world we are building, and in this sense the cultural evolution is progressing very rapidly.

In the 1990s, there were lots of ideas revolving around the fact that we now have a global internet and so there has to emerge a global brain. And yet there are not that many projects moving toward that ‒ perhaps Wikipedia is an example. Since its launch in 2001, the ‘energy of the masses’ have been mostly used by the big companies for their own purposes.

As for human feelings and psychology ‒ were they the same 500 years ago? I think a lot depends on culture and religion. Or perhaps on geography: it is always about the South and the North. There are serious cognitive differences, and they still remain intact. In this sense, I also think that men and women are quite different; it is a miracle they don’t kill each other. But is it possible to change that, is it possible to raise people who will not envy each other or who will not feel a desire for revenge? Lots of science fiction has been written on the subject. But almost in every story there is this situation where society has changed human psychology and there are some unexpected and not always very pleasant consequences.

If we consider European culture, historically, it is a culture of feelings, emotions, passions. Caravaggio, Rubens, horror films, Vysotsky, all these random confrontations in bars ‒ in this tradition, the human being is still a bit of an animal. And it is perhaps exactly because of this that it has been an extremely interesting and exciting culture. We’ve had films with crazy editing, we’ve had crazy poems. There was a huge emotional range to this culture. But over the last few years, we have been witnessing that there are new values emerging in human society, that it is becoming extremely sensitive regarding any inequality. Things like #MeToo are emerging; the subject of minorities is becoming more and more topical, and it’s not just in America.

As a consequence of this, there is a kind of cautiousness growing, both in cultural production and in people’s behaviour: what if I say something, what if I offend someone and get fired? It is very obvious in America, but Europe and even Asia are not that far behind. There is this sense of the range of emotions shrinking in developed societies, because certain emotions are being declared bad. In the United States, they are starting to take Gauguin’s paintings off of museum walls because he painted Polynesian girls with whom he was living. A certain moralist censorship is emerging. And there is undoubtedly a positive side to all this. But it could potentially also have a negative impact: there is this feeling that the emotional, passionate, revolutionary, depressive 20th-century man is being replaced by a character permanently using some antidepressants: he does not rejoice much, he does not grieve much; he is constantly scared of hurting someone’s feelings… And most importantly: he is afraid to do the wrong thing ‒ fall in love with the wrong person, start attending the wrong institute. And therefore, he has this need to rationalise his own behaviour all the time.

And so this situation, where global competition is emerging all around us but we, on the other hand, are constantly accompanied by both the fear of offending someone and a feeling of shame for our culture in the past ‒ these are already very significant things. If people have feelings, they do not openly show them. Everybody has become so very polite. And if someone is rude, they are almost like from a different planet. They have set up cameras everywhere. Everything must fit certain standards. But all of this has nothing to do with AI; AI is merely a tool used in these processes, in these transformations of the emotional tonus of society.

Lev Manovich. Photo: Дмитрий Зиновьев

Meaning that, yes, we are changing, but we are still changing ourselves, just like we used to?

AI is a myth created by society. There are just certain algorithms solving certain problems. Apple phones have new software that follows how you are washing your hands, and it announces that you should be doing it for 30 seconds. What is this ‒ AI? No, it’s just an app.

Yes, an efficient app. Which takes us back to the subject of ‘interesting mistakes’…

Not quite. The subject of errors and glitches frequently surfaces in this discourse. This is not the way I think. I am not particularly interested in the subject of mistakes, because I grew up in the Soviet Union where nothing ever worked ‒ at all. For this reason, I love it when things work.

Of course. But we are referring here to the significance of the irrational element…

Irrational, emotional, the situationist flânerie. This random movement around the city. Accidents in general. This thing that seems to be so very unlikely…

All of that acquires an additional value…

Yes, but the fact that AI is used for universal rationalisation, for self-control and self-surveillance ‒ Foucault also said all that. Everything is happening exactly the way he wrote about it. And yet, the problem here is not AI; the problem is that we want it. That society wants an increasing rationalisation of behaviour, traffic, energy. It wants to make things more efficient. AI is a mere tool in our hands. We should not fear AI, we should fear ourselves.

I agree.

The world used to be so cruel that nobody could be sure that they would make it to tomorrow. The situation has changed over the course of the last couple of centuries. Furthermore, the world’s middle class has grown from 700 million people to several billions over the last twenty years, mostly because of the Asian countries. And when people have found a certain level of welfare, what is it that they want? Stability, control.

In our time, consciousness has completely taken control over unconsciousness, the subject of endless research and reflection by Freud. I would say that we should think about helping ourselves come out of our shell and reclaim our irrationality. At that, we should not, of course, go back to things like male violence against women. Could we get back some irrationality while still being good human beings? Now, this one, I think, could turn out to be the key question of our times.