Orchidelirium: An Appetite for Abundance

An interview with curator Corina L. Apostol and artists Kristina Norman and Bita Razavi – the creative team behind the the Estonian pavilion at the 59th Venice Biennale

For the upcoming 59th Venice Biennale (2022), the Estonian pavilion will exhibit a project by artists Kristina Norman and Bita Razavi titled Orchidelirium: An Appetite for Abundance (curated by Corina L. Apostol), inspired by Emily Rosaly Saal’s (1871-1954) watercolours and paintings of tropical plants. In the exhibition the artists combine historic and new artworks to propose a multifaceted view on colonial history and its problematics.

This project started with a collection of some three hundred images of tropical flowers, fruits, and vegetables produced during the first decades of the 20th century by a forgotten artist from Estonia named Emily Rosaly Saal. Her works depict plants from different corners of the Dutch East Indies, then under the Dutch Empire, where she lived and travelled with her husband Andres Saal between 1899 and 1920.

‘When ordinary people become protagonists of vast histories, they often complicate perceptions of both national histories and colonial project(s). Our proposal for the 2021 Estonian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale takes this as its point of departure through exploring the forgotten story of the 19th century artist and world traveler E. R. Saal. Her work and history serves as a case study for the entangled histories of Estonian self-determination, Western colonialism, botany, science, and art. The project brings a novel understanding of Estonia’s history in a world system where power imbalances influence how the human and the natural intersect,’ state the artists and project curator Corina L. Apostol.

Kristina Norman (1979) is a Tallinn-based artist and documentary maker who explores the converging trajectories of national identity, the politics of memory, and public space. Norman’s most recent work is a poetical documentary performance entitled Lighter Than Woman, whose protagonists are women who overcome the ‘gravity of life’ in both a metaphorical and literal sense.

Bita Razavi (1983) was born in Tehran and is currently living and working between Helsinki and the Estonian countryside. Her work looks at everyday situations which become the basis for making broader conclusions about the surrounding culture and society. In one of her latest projects, Museum of Baltic Remont (2019), Razavi built a commemorative scientific installation to showcase the invisible building materials that many people in the Baltic region live amongst. Corina L. Apostol (1984) is a curator at Tallinn Art Hall and the co-curator and coordinator of the international project Beyond Matter – Cultural Heritage on the Verge of Virtual Reality.

The exposition of the Estonian pavilion in Venice will open in April 2022 and will be hosted at the historic Dutch pavilion in the Biennale’s main exhibition grounds in the Giardini.

Arterritory.com sat down for the following interview with artists Kristina Norman and Bita Razavi and project coordinator Corina L. Apostol.

The beginning of your project was a collection of approximately three hundred images of tropical flowers, fruits, and vegetables produced during the first decades of the 20th century by a forgotten artist from Estonia named Emily Rosaly Saal. How did you find this collection, and why did its reflection on the history of colonialism and its consequences seem relevant at the moment?

Corina L. Apostol: Emily Saal’s paintings depict plants from different corners of the Dutch East Indies, then under the Dutch Empire which comprised a significant swath of the globe. They were to be incorporated into the publication ‘Representatives of Tropical Flora: The most important and interesting from the plant world of Java’, which also included explanatory text and photographic images by her partner Andres Saal. The manuscript was never published and is in the archives of the Literature Museum in Tartu. The Saals retired to Hollywood, CA in 1920, and a few years later in 1926, Emily had a solo exhibition showing all her works at the Los Angeles County Museum of History, Science, and Art. I retraced that exhibition and was able to find several lithographs of her works scattered throughout different galleries in the US. We are still looking for the entire collection. During our research, we also received guidance from Grace Samboh, who is a writer, researcher and curator based in Yogyakarta; she had a very important role in shaping how we thought about colonial history from a local perspective.

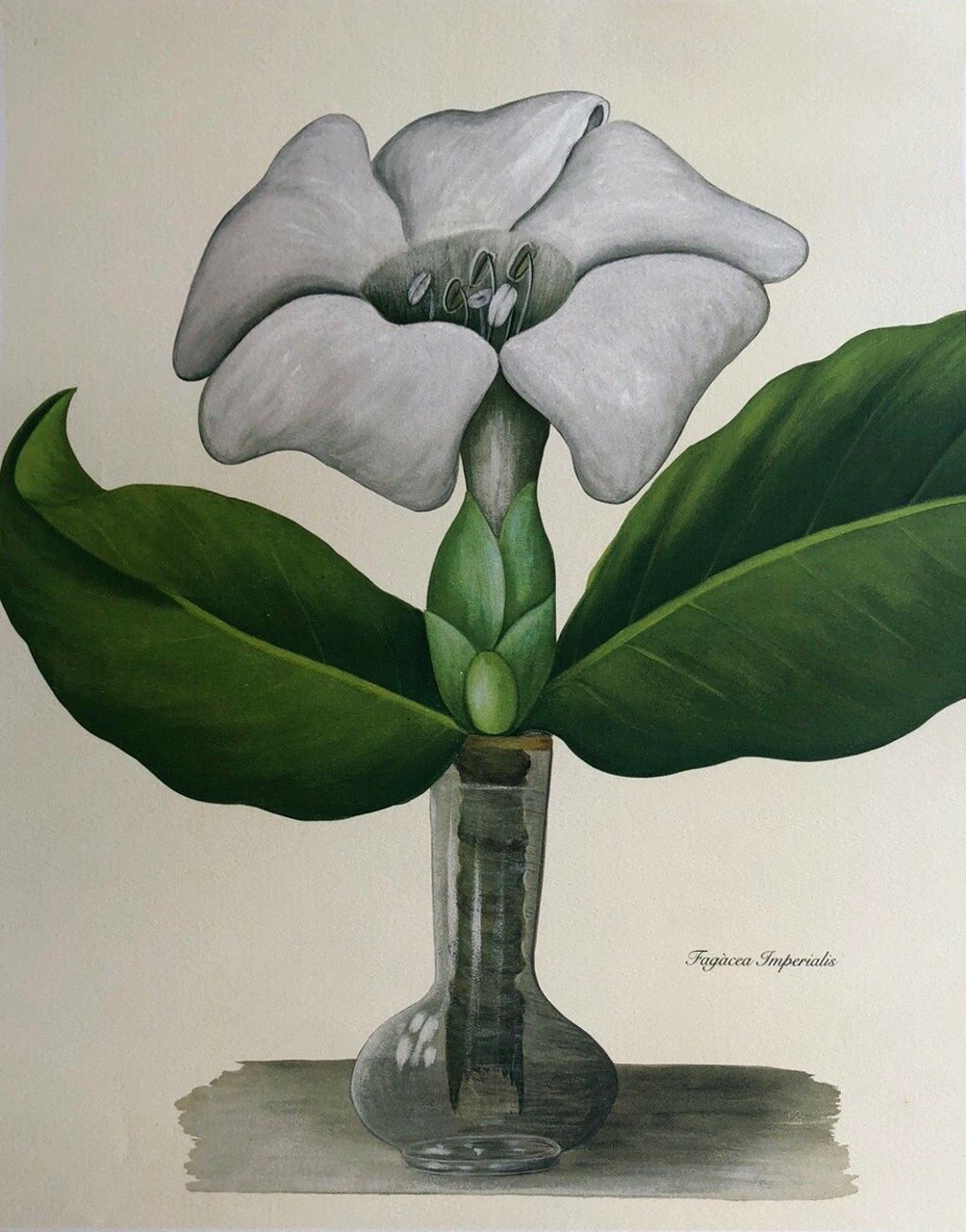

Emilie Rosalie Saal "Michelia Campaca", ca 1910, newly print 1995

Emily Saal’s works depicting flowers forever in bloom and perfectly ripe tropical fruits are not realistic depictions of any specific living plant, but rather are idealized representations. She used a standardized iconography in Europe at that time, in order to combine multiple plants together, as well as to compress space and time so that the images included the information that botanists desired. Likewise, our project proposes to do just this in order to complicate the historic definitions of nationhood, belonging, and colonial exploitation of that which is deemed ‘exotic’. Saal’s works and its historical material will be embedded in an intriguing take on a conceptual garden that is conceptualized by Bita and a film trilogy by Kristina. We imagine the exhibition space itself as a play between what we see and what is invisible.

We imagine the exhibition space itself as a play between what we see and what is invisible.

Kristina Norman: It is true that before we learned about the collection of Emily Saal's botanical paintings and got impassioned by it, the artist herself needed to be re-discovered for the sake of global art history. And this happened when I was reading a biography of Estonian writer Andres Saal, Emily's husband. He’s been somewhat forgotten, but at the end of the 19th century he was an author of very popular national romanticism novels, first about the Estonian anti-colonial struggle, and later, after having moved to the Dutch East Indies, two novels about the Indonesians’ resistance to Dutch colonial rule. Ironically, a few years later he accepted the position of head of the topography department for the Dutch colonial army in Batavia. While reading this life story, Emily appeared as a footnote character, a wife of a remarkable man. But from between the lines, I learned that Emily was a painter and that after 22 years of work in Indonesia, she had a huge solo show in Los Angeles, in a place similar to the Venetian Giardini. After this discovery, we were thrilled to shift the focus of our research from Andres to Emily and so far, it's been a fascinating detective investigation.

Bita Razavi

What did you understand about humans and our relations to the land while working on this project?

Bita Razavi: Emily’s husband Andres Saal was the head of the military cartography department of the Dutch colonial army. Just as Emily mapped the exotic nature and plants, her husband mapped the exotic land. So he wasn’t only a simple worker who was paid by the Dutch East Indies but had a significant contribution to the colonial system. Maps have always been a form of political control by Western colonial powers. They were cheaply and widely mass-produced so that every middle-class western citizen could hang one in their living room and bear the idea of the colonized lands as visual ownership. Maps were always the depiction of the colonizer and his relation to the land. Even if they didn’t have enough information about the land to make details on the map, colonists rarely used information from locals who had lived in these territories for generations.

Maps have always been a form of political control by Western colonial powers.

KN: Nationalist accounts of history are closely tied to territory and borders. The Estonian history of striving for national independence has always been narrated through the urge to cast off foreign rule (be it German, Russian, or Soviet) and become part of Europe. But ideas about what Europe and Europeanness mean, are in constant flux. The recent ‘refugee crisis’ introduced the category of race in the Estonian collective imaginary and caused old and new divisions and invisible borders inside society to resurface. It also provoked yet another discussion within the European Union which defined Estonia along with other Eastern European countries as ‘less European’ due to their reluctance to accept the refugee quotas. The reasoning of the Estonian side was grounded in the continuous need to struggle with the unwanted legacy of the socialist past, and in the fact that Estonia should not be held responsible for the injustices of Western colonialism. In my recent works I have addressed migration, historical injury, and Eastern European identity in the Western European context through the prism of post-socialist experiences. In my new work I'm digging deeper into history to see if it's possible to narrate the history of the Baltics not as one of suffering and victimhood, but as of a place that has always been on the crossroads of different cultures. I want to show that the biographies of people who lived here reach far beyond regional and state borders and connect us to distant territories, and that some Estonians had agency and influence on histories of other peoples and cultures.

Do you agree that plants are a wonderful conduit to culture?

BR: Sure! Just as any other subject could be. I think that is the beauty of art and culture – that it can derive from anything. But I would like to emphasize that what we are really discussing with this project is not plants but human’s craze for plants. We are not romanticizing nature or plants; we are looking at a social issue around them. For the Estonian pavilion I’m creating a conceptual garden to look at colonial history and its problematics, such as class, privilege, hierarchy and other subjects, through the representations of plants.

We are not romanticizing nature or plants; we are looking at a social issue around them.

KN: Another notion that connects our project to the history of colonialism and the white man’s scientific gaze adopted by the protagonist of our project, is that of classification. I was speaking with historian Ulrike Plath from whom I was fascinated to learn that in Central European scientific writings from the end of the 18th century, Estonians appeared as ‘Europe's last savages’, one of the unknown peoples on the Northern margins of the continent. In Johann Gottlieb Herder's classification of men, Estonians are considered to be at a similar stage of wildness as African, Sami and Siberian peoples. I am trying to imagine Emily Saal’s biography against the backdrop of the German colonial discourse and it is intriguing to think of her transition from a racialized native ‘other’ in the Baltic cultural context into a representative of the white colonial élite in the Dutch East Indies at the beginning of the 20th century. The project will look into her professional career as a female painter and analyse it in the context of cultural and racial codes. I suspect that she was able to emancipate as a woman at the expense of the labour of indigenous Indonesian women who took care of her children and her household and secured her the spare time to dedicate to the science of botany and painting.

Are all of the plant species from Emily Rosaly Saal’s collection still growing in their native lands, or have some already gone extinct?

CA: We have yet to trace all of the species in the Saal collection, but an additional focus of our research besides orchids has been palm trees, in particular the exploitation of palm oil in Indonesia, which has been driven by capital, land availability, low-wage labour and the international demand for palm oil products. One can trace the desire to exploit the environment and transform the landscape back to the colonial period, when Europeans enforced modern agriculture in this part of the world. Culture played an important part in this process: extensive maps, depictions of lush, open landscapes, wild plants and the omission of local laborers and those who would resist the colonizers cleared the visual field for the intervention of European scientists, entrepreneurs, and the military. Today, the exploitation of palm oil and deforestation in Indonesia is happening at the same time as local companies are creating so-called shelters for rare orchids which they wish to save from extinction.

Corina L. Apostol

The lifespan of Saal’s images of these plants, which inspired our original research, has endured beyond the culture and politics that sustained them. Her collection further opened the biodiversity of the then Dutch East Indies to the world, bringing tropical plants closer to scientists, gardeners and the elite in Europe in the twilight of the Dutch colonial period. As such, this collection cannot be separated from the imperial polity that enabled Saal to create her work, just as we are now piecing together how deeply intertwined slavery, science and botany were.

Today, the exploitation of palm oil and deforestation in Indonesia is happening at the same time as local companies are creating so-called shelters for rare orchids which they wish to save from extinction.

Which is the most unique plant in Emily Rosaly Saal's collection and what makes it special?

CA: The title of our project, Orchidelirium, references the 19th-century orchid craze during which a fascination for collecting the flowers erupted into hysteria. While orchids are now commonplace in our society, they used to be exclusively the purview of the elite, and hunters were employed to track down exotic varieties in the wild and bring them to collectors. Emily paid special attention to these flowers, dedicating more than 100 of her works to different types of orchids. Using this observation as a starting point, we hope to bring a novel understanding of Estonia’s history in a world system where power imbalances influence how the human and the natural intersect – in commonplace items such as orchids. We plan to address the many layers of Dutch-Indonesian botanical history, including the exploitation of orchids by naturalists and merchants and the desire to protect, cultivate, and scrutinize by scientists and artists.

Emilie Rosalie Saal "Fagacea Imperialis", ca 1910, newly print 1995

KN: Our project is rather critical of the concept of uniqueness. The quest for unique natural objects and the ‘exotic’ is what has been driving capitalist greed for centuries. The tradition of collecting curiosities in the colonies and showing them in zoos and botanical gardens in the imperial metropoles is exactly what lies behind the extinction of species. Ironically, zoos and botanical gardens today appear to be the very last habitats of many species that have been excavated to near extinction or whose natural habitats have been replaced by mines or plantations.

The quest for unique natural objects and the ‘exotic’ is what has been driving capitalist greed for centuries.

Can you give us more details about your artistic contributions to the Estonian Pavilion?

KN: For the pavilion, we are planning to dive deep into the archives in Indonesia, US, Holland, and Estonia to find documents that will help us to better imagine Emily, her art, and to reconstruct the material conditions of making it. Beside other things, the project is an exploration of performativity of class and race through the prism of colonial architecture which surrounded Emily and her art in all the three main geographical places connected through her life story. Bita, who has her own vision and approach to the subject, will develop them inside the pavilion in her site-specific installation in the form of a garden.

In addition to that, I’ll be collaborating on a film trilogy with choreographer Teresa Silva, composer Märt-Mati Lill, as well as Erik Norkroos who will be director of photography. With Erik we have worked together on a number of projects since 2006 and we also have collaborated with Märt-Matis before. Now we are looking forward to starting experimenting with Teresa. Using choreographic means, she has been exploring human-plant communication as a theme in her own artistic practice.

CA: Throughout the process we are also closely collaborating with Aet Ader and Arvi Anderson from b210 architects, who are supporting our approach to transform the pavilion space to best showcase the intertwining key notions that the artists are expanding upon in their contributions. I am also planning to edit a special publication that will offer the viewers a deeper understanding of the research underpinning the project and its contemporary relevance, with contributions from specialists noted by the artists, such as Grace Samboh, Tashima Thomas (Pratt Institute) and Ulrike Plath.

There has been a remarkable trend of exhibitions in the last years about nature in the art world and, in some way, also the feeling that art is leading the way in promoting radical ecological awareness. In the meantime, there are worries that it is just a trend and that nature could go ‘out of fashion’ again. What is your opinion? How strong is the voice of art and does art have the power to change something?

BR: I think nature-related exhibitions are already out of fashion. Every institution has already fulfilled their duty of responding to the trend by making at least one ecology/nature-related exhibition during the past few years. So, I don’t think we should be worried about not seeing those exhibitions anymore, but we should see if all those trendy exhibitions raised any discussion and made any impact and change outside the small bubble of the contemporary art scene.

Kristina Norman

KN: Artists should help the romantic notion of ‘nature’ to disappear for good and put the notion of environment in the middle of public consciousness. The notion of environment acknowledges the human presence and its effects on everything that surrounds us. The construct of virgin, untouched nature is, first of all, closely connected to social class, and it also explains the popularity of landscape paintings. The ‘beauty of nature’ historically was – and still is, and maybe even more so today – accessible to those who have the time and a place to enjoy it. It also shows our will to abstract ourselves from signs of human activity and to turn a blind eye to the effects of human presence on the surroundings, thus making us forget our responsibility and agency to preserve and protect. I believe artists can do a lot here.

Artists should help the romantic notion of ‘nature’ to disappear for good and put the notion of environment in the middle of public consciousness.

CA: In the past few years, discussions about sustainable futures, civic ecology, environmental education and resilience have indeed intensified in the arts. Infusing art’s unique power of communication with a sense of urgency, several artists whom I have worked with, as well as writers, poets and dancers for the ‘Creative Time Summit: On Archipelagoes and Other Imaginaries in Miami’ (2018) and the ‘Shelter Festival: Cosmopolitics, Comradeship and the Commons’ (2019), have contributed to the public’s awareness of the economic, political and systemic conditions that affect our collective futures, and even developed ideas for green solutions and scenarios. There is quite strong cross-pollination between artistic tools and ecological education, and I don’t think this will go out of fashion, even if the media attention to it may wane. I believe that, together with renewed forms of resistance and solidarity, we need to continue the process of learning from nature and fight against the exploitation that is happening on a global scale.

Returning to our own proposal for 2022, we are taking into account the position of the Estonian pavilion, and plan to address the history and location of the Rietveld pavilion itself and the establishment of the national pavilions in the Giardini, looking critically at the relationship between national accounts, the environment, and global exchange.

If we look at this pandemic as an opportunity to re-evaluate/questioning our attitude towards the things we used to, models of existing, and the idea of how we are going to live in the future – what are the main lessons the art world should learn from this crisis?

CA: In my view, we’re not only in the middle of a virus outbreak, but also of a pandemic which reveals inequalities that are long ingrained in our communities and way of life. Culture continues to thrive nonetheless, and I’ve seen a lot of innovative platforms that have been adapted to this period of containment, from digital platforms to online symposiums, to art on balconies. There is acute awareness that as this crisis continues, we need to act to support one another, moving beyond competitions and grudges, but also address the injustices of the past that have been ongoing. The truth is that we do not have easy answers to how we are going to overcome this pandemic. There is a lot of anxiety about the future, however, we can learn from this moment and reset the machine, do away with it altogether, or turn it into something completely different.