Schachter-istically outspoken

A conversation with Kenny Schachter

Guess the riddle! He is a direct, simple, and honest person – sometimes harsh – but infinitely enjoyable. Although he doesn't take himself too seriously, he is deathly serious about art. He is one of the most disruptive and influential of Artnet’s columnists, is not afraid of stepping on the toes of the art world's most important players, and is merciless in regards to himself while taking an almost fatherly approach when it comes to emerging professionals. He is a member of the University of Zurich Art Market Faculty and an ecstatic storyteller on the ethical approach to the art trade. His personal art term glossary has introduced the word spec-u-lector, as well as a new human-animal: the art market beast. For him, good values do not rust, i.e. old automobiles, vintage Adidas track pants, and of course, honesty. He seems to be smiling from ear to ear all the time. Who do you think this person is? Answer: the renowned American art writer Kenny Schachter!

Since the late 80s, Kenny Schachter – art market reporter, lecturer, artist, and so much more (a veteran ‘dealer-to-dealer’ dealer, art collector, art world provocateur, etc.) – has become a towering figure in the international art scene. Completely unaware of the fact that 'art and commerce were bedfellows' until well into his 20s, Schachter started his adventures with visual art in New York curating 'pop-up art exhibitions before the term “pop-up” even existed'. In 2004, after moving to London, Schachter became a writer for the website Artnet.com, where he brings unprecedented radical transparency into art market reporting. In doing so, he provides direct answers to particularly cringey, yet fair, questions in the art trade: What is the price? Do the actual transactions correspond to the sums publicly released? What other paranormal activities happen in the art industry besides ‘ghost bidding’ at auctions? What is it that drives prices up to mind-blowing amounts?

The art market is composed of a global infrastructure, social relations, financial transactions, and much more. Much like a drop of oil in a glass of water, the art industry reacts to tectonic shifts in the worldwide economy while also enclosed in its own economic ecosystem. Another comparison comes to mind: paraphrasing the late artist John Baldessari, when artists attends an art fair, it’s like a child walking in on its parents having sex. This intimate act could be more accurately described as 'art dealers operating within the private world in which works of art are bought and sold through handshake agreements and bargaining for the highest commissions'. Kenny Schachter's entire career has been about analysing the commercial dissemination of art, thereby providing his readers with comprehensive behind-the-scenes information. He writes about exclusive art deals, contractual dispute controversies, and sometimes, the often speculative nature of the art market.

Having left London, for over a year now Schachter has been living in New York. His home is where his eclectic art collection is. Schachter's office is brimming with a wide array of artworks, amongst them a small, almost childish painting of a star which is very precious to him. For him, art is so much more than what he writes. Case in point: I had yet to hear the word love uttered so many times by an art collector when referring to their private collection.

Is Kenny your full name?

It's Kenneth.

Now I can trust you without us having shared a drink beforehand.

Hah.

Going by our email exchange, you are a man of few words – which seemed so un-Schachter-ristic when compared to your usual public output of the written word.

I simply can't stand small talk.

Neither can I. You are known as an art dealer, an art market columnist, an artist, curator, lecturer, art world provocateur… and so much more. Is the order of these titles important to you?

The things that are most important to me are writing, teaching, and making art – in that order. The busier I am, the more I can achieve. You can always find time for the things that are important to you.

I've created a platform that didn't exist before. It contains short narrative digital videos as well as 3D-manipulated photographic works by me which illustrate my articles. My writing is my art, my curating is an art form, and my art is whatever it is. I love teaching and collecting art, but I sell art to make a living. I am a ‘dealer-to-dealer’ dealer. I always joke that I can't sell drugs to a drug addict, therefore I've never really spent my time selling to private collectors. They're very fickle, and capricious. And I just don't want to spend my time explaining to people why they should like something. I believe that good art has very objective inherent qualities. But I love to teach, to give lectures, generally speaking, but not with a view towards making an acquisition.

For example, I had my second hoarder auction at Sotheby's. For me, this is the best of all possible worlds. None of the works on auction are recently purchased. I don't believe in selling recently acquired art works, also commonly known as ‘flipping’. These are the works that I've acquired over many years. The Sotheby's auction house takes care of logistics, clients, shipping, basically all the things I just don't have to pay attention to.

In 2019 and again in 2020, Schachter partnered with Sotheby’s in holding an auction affectionately titled ‘The Hoarder’, with proceeds benefiting himself. The eclectic selection offered everything from photographs and paintings to furniture and a 1972 Porsche 911S, including plenty of affordable works that Schachter was glad to pass into the hands of someone looking to start an art collection. – Ed.note

So, for instance, because of economic necessity during the COVID19 crisis, I started to launch a series of selling exhibitions online. I've managed to sell around 40 artworks, if not a bit more. All deals were closed digitally – without speaking to anybody, without any kind of physical, real life interaction. So it's been the best of all possible worlds. The revenue hasn't been loads of money by any stretch of the imagination. I never sold anything through those selling shows for greater than $10,000.

This is how I sell art works commercially. Mostly I earn through writing, but that's not why I do it. Pretty much anything I do commercially, I would do for free.

Moma Covid-19 © Kenny Schachter

How do you decide that you are ready to resell a particular portion of artworks?

There are some things that I won't let go of. I see myself as ascetic in the way of self-denial; on the contrary, I am materialistic because the whole world is surrounded by works of art. Not a day goes by when I won't rub my nose up against a work of art and think about it, touch it and smell it and everything else. There's only so much stuff I can live and spend time with. I also have to make a living.

I hesitate to give up works from my collection, but after some time, there a few that won't make me sad to part with them. I never work with things that I don't like, whether commercially or for myself. I don’t get (too) attached to anything. I can get rid of anything and I wouldn't care as long as I was able to replace it with other works of art that challenge me, and there are plenty. In a way, it's just a hierarchy of how I feel about something in the given moment.

What are you surrounded by at this moment?

My home in New York is literally brimming with things. I'm a maximalist. I must have, let's say, 100 items in this group of objects that are very important to me.

I have a Paul Thek sculpture from 1975 which is composed of 23 tiny bronze mice. Each of them is hand formed by the artist and completely different. Paul Thek is the most meaningful artist in my life. (Shows a mouse sculpture in his palm) Oops, I almost dropped it! Anyhow, that's something I will never sell. I have somewhere here a Sarah Lucas sculpture...Tracey Emin's work of her beloved Docket, the cat. Honestly, there is nothing terribly big or expensive (turns the computer camera around the room to give me an overall impression).

Many works of art were given to me as a gift by their authors.

Do you change the display of artworks at your home?

I generally don't change them because I obviously love to see them.

What is that blue chair you have over there?

Oh, that I designed myself.

Many of the items in my collection are important to me for personal reasons because they enhance my life. For me, works of art are the physical manifestation of thoughts. I have a signed poster from Christopher Wool's first text painting exhibition in 1989 at Max Hetzler’s gallery, which was in Cologne at the time. It's a poster. Surely they printed a couple thousand of them, so it's not limited in any way. If I had Wool's painting worth $8 million, it would still have the same impact on me as a signed poster of it. I like it even better as a poster...besides the fact that I don't have $8 million. I would be tempted to sell the painting if I ran out of money because it would be by far the most valuable artwork I have.

For example, I like old cars. I like industrial design in general and the care with which objects were made. I'd get more satisfaction with a car worth $20,000 than I would with a car worth $2 million. The price would completely change the entire relationship with the car. A car should be driven, and a sports car should be driven hard...but safely, of course.

The point is, I have no hierarchies to my democratic collecting habits, and I don’t differentiate between a signed poster or a painting, chair, spoon or fork. I love things that are made with love, passion and attention to detail.

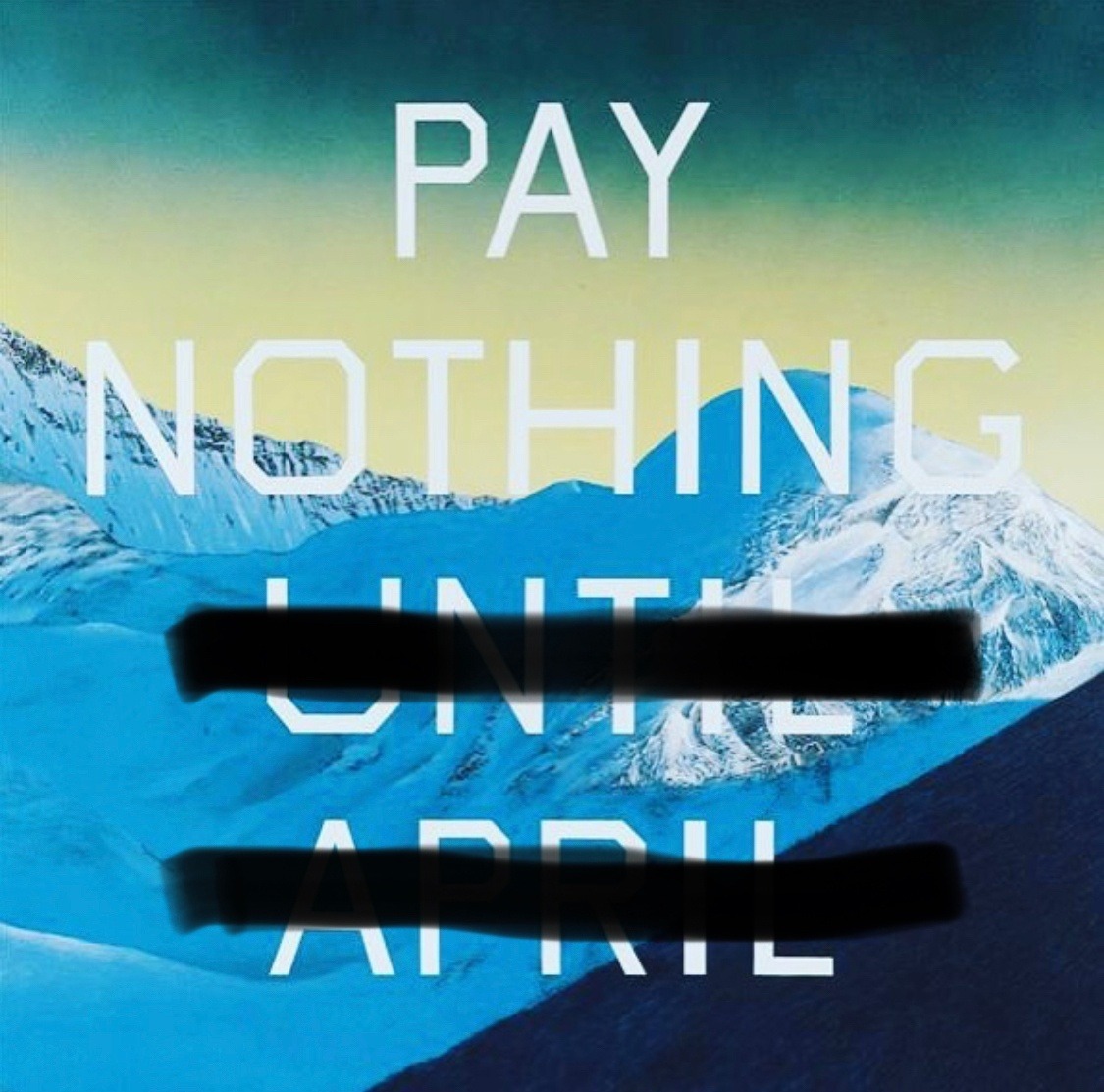

Kenny Schachter, Pay Nothing (2020) © Kenny Schachter

Tell me about your writing conditions. For Proust, it was the ‘petites madeleines’ that triggered a deluge of memories with which he filled long and ponderous volumes.

For 15 years my office in London was a converted garage with only a sliver of a window; and, the nose of a car under my desk. Now I have a sun-filled space in Manhattan. Basically, I could work in the street if I had a laptop, desk and chair.

Before I had an iPhone, I liked the Blackberry keyboard for writing down notes. When I'm in the trenches writing an article, I typically write notes that I email to myself and that's the first stage of my writing. Then, in front of the computer, I pull all the emails into one file. I move the notes around, get an arc of the story, and then I spend one to two days putting it in a cogent form of paragraphs. While writing, I'm listening to music – typically one song repeated at a deafening level of sound for three days, up to 10 to 12 hours a day, until I can never hear that song again for the rest of my life. I connected speakers to my computer that are not known for their quality of sound, but probably for being the loudest wireless speakers. When the music is blasting, in a way, it blocks everything out. I concentrate on what I'm doing and I barely hear it. It's not classical music, jazz or techno. My playlist contains rock, indie, and the kind of funky new rock which is more on the extremes of the margin – which is where I like to consider myself. I also consume a lot of coffee. That is just how I like to work.

Why do you emphasise being an outsider? From my point of view, you navigate very well within the art world.

I'm sort of an inside-outsider, which I'll always be. An outsider because I never studied art. I am completely self-taught. I have been teaching PhD students at the University of Zurich for nine years. I've been teaching studio art at the School of Fine Arts for almost 30 years. I always tell my students that they shouldn't hesitate to contact me. I will reply, and I will reply personally and promptly – which may set me apart from most people in the industry. If I can anyhow be in service and help them, I will – and I do. I like to inspire people the most and foremost.

I never had a job within the art world. I work by myself. I'm an outsider because I'm really not normal. I don't work within normal constraints or in normal streams in commerce. I work in my own independent fashion.

From the first day I walked into a gallery, everything I did was in critical response to the art world and the machinations of the stream of commerce as it relates to the dissemination of art. It's an environment unlike any other environment in the world.

There's a lot of hegemony in the art world, and a lot more uniformity of thought. I'm not cynical – I consider myself idealistically cynical.

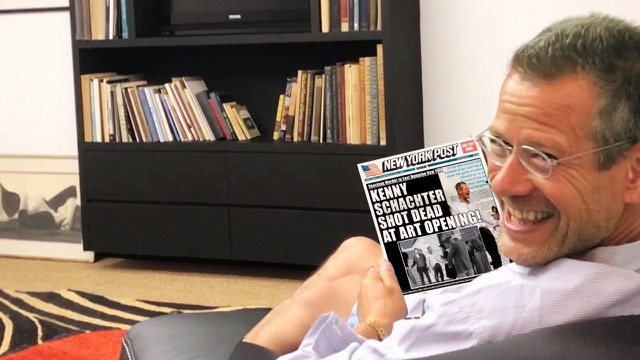

I'm scared of a lot of things in my life; I'm a coward, I guess. When I'm sitting behind the computer, I'm fearless. And honestly, if I got shot today, literally, it may sound melodramatic, histrionic, and exaggerated, but nobody would be surprised and I couldn't care less. That's the cost I would pay to stay true to myself.

Self(ish)ie from Kenny Schachter on Vimeo.

I must say that it is easy to talk to you. You even helped me for 45 minutes to solve technical connection problems before we could speak. It is a person's honesty and kindness that I value above all else. How do you think people in the industry perceive you?

There are some people who don't like me that much – because of my frankness and the fact that I am so straightforward in my writing. Some have threatened me with lawsuits, but I've never been actually sued. Since I am telling the truth, I cannot be sued.

I make mistakes. I am not always right. That is part of being a human. If you don't fail, you are not trying enough, not working hard enough, and you are not challenging yourself enough.

For the most part, I would say at this stage of my career, the majority of the art world that reads me appreciates that I provide in-depth information about a world that is very opaque and prides itself on secrecy and not opening up about the simplest of things. And when they do, it's peppered with lies because the art world is one of the few professions that celebrate and embrace ambiguity and myth-truths about money, about the machinations of business. They are frightened to the truth. These are the things I strive to pull back the curtain on and share. I'm kind of an investigative journalist.

How do you get information about things that most likely take place behind closed doors?

None of your business. Hah!

Bravo! You couldn't have said it better.

Because of the fact that I've been doing this for so long and with such determination, people trust me. Access, which is so important in the art world, is all done through personal relationships and friendships. They better be sure and confident of what they're saying. I recoil from the term gossip in my writing. It's in human nature to share information. People like to see things enter into the public realm. ‘Deep Throat’ was the pseudonym given to the secret informant who provided information to reporters who uncovered the whole Watergate scandal in the USA. I had a character called ‘Deep Pockets’, who was based on this anonymous source. So there's always people that have information, and I'm going to express it.

I’m sensing a tone of dismissal in your voice concerning the gallery business. What is your standpoint?

Well, in the beginning, I was a lot more critical of galleries. This year the thing I miss about going to fairs and travelling the whole art circuit, generally, are the people that make up my closest relationships, artists, and gallery people. I love to work with art directors and gallery owners. I really feel that they have made the biggest leap of faith in their lives – to embrace art with all the difficulties that entails. And selling art is a real struggle. I appreciate people that are worker bees in the art world.

I believe that running a commercially successful gallery is one of the most difficult businesses. You know, small to medium galleries have never had a viable business model from the first day a small gallery opened. Of course, small galleries have turned into big galleries. But you know, there's some degree of futility built into the business model of an upgraded gallery. The moment you succeed, you also fail, because when the artist gains notoriety, they find a bigger gallery that goes to more art fairs, that has more money for production, and that has a bigger base of collectors.

I don't always agree with the manner in which gallerists do business. The last power that art galleries have is granting access to buyers to buy art that everyone else wants. That's what it's all about. You have this kind of waiting list of who's more important than you: someone wealthier, someone that has a private museum, or someone else that beats the next person and gets offered the best work. That's the way it's always going to be.

Do you do political analysis in order to support your activities and protect yourself from criticism?

I never really thought of that. The very first day I put my foot into the art context, I was frank. That's simply my nature. Probably because I never learned what you can't do or say in the context of the art world – I just simply did it. You learn to not speak about basically anything while making your way through the gallery system. The first time I stepped into a gallery was in my late 20s. The reason for not going to galleries before was that I didn't know they existed. I went to museums while in university, and I naively thought that art is sold in museums. I had no notion of what the art trade exactly is.

Years ago, Greg Smith's resignation letter from American investment bank Goldman Sachs was published in the New York Times. I used Smith's letter as a kind of template to compare the financial market with the art world. In the end, every time the word ‘Goldman Sachs’ was mentioned, I substituted it with the word ‘Gagosian’, and ‘financial investments’ I replaced with art context, like ‘Mike Kelly's installation’, and I reprinted the article in a newsletter. Some people mistook it as a true article although it said that it's a satire, but obviously they skipped that part. And it went viral. The article was read hundreds of thousands of times. To this day I get stopped by people thanking me for inspiring them to quit their job or for just standing up to authority like that.

Schachter wrote a satirical piece on the monetisation and commercialisation of the art world using Greg Smith’s resignation letter as a foundation.-- Ed.note

www.instagram.com/p/CDH1KUggERc/

I adore Larry Gagosian. He is one of the greatest art dealers in the last 100 years. There was a while where Larry disliked me and would speak very badly about me. In the course of time I started to speak way more favourably than unfavourably about him. We have forged a good relationship.

I mean, if something came up, I would never prophylactically edit or censor myself for any reason – nothing would get in the way.

When it comes to the fact that I have a big mouth, and the reason why I don't give a shit about anybody or anything, in terms of talking about the nefarious activity in the art world, is that I am not relying on working for an art gallery or even Artnet. I have enough in my collection to sustain myself and my family. As a result, I can act in a way that may be considered a little bit reckless, but always with a sense of purpose. I would never write to be vindictive. If I were ever knowingly insincere or dishonest, I would lose my audience.

Can I help you find something. Kenny Schachter presiding over his Sothebys sale © Kenny Schachter

How often do you manage to step on someone's toes?

I mean, a lot.

Just a year ago, this well-known antagonistic lawyer, Aaron Richard Golub, who's the lawyer for many famous players in the art world, called me a ‘fucking asshole’ at the top of his lungs and threatened to beat me up in the middle of New York’s uptown art canteen on Madison Avenue. I was a little bit nervous. I've never willingly got into fights in my life. I was beat up very often when I was younger and bullied. But I will never be scared to write about that experience. And this man's behaviour. If I believe in something, I will do anything to espouse it.

I have been accused of all kinds of terrible things on social media. People who haven't even met me have accused me of harassment just to get the art world to dismiss me. None of which is true. Nothing will stop me. Nobody. The only one who is capable of stopping me is me.

This summer I was suspended for three months from writing in Artnet because Sotheby's accidentally gave me wrong information that may have been correct on a certain level, but was wrong technically. The seller of an Amoako Boafo painting even tried to sue me.

So I'm like a rock in a stream – you may shut me down in one place, but I'll appear in another place. If I would lose all of my platforms to write on, I will just publish it myself, like I did. I wanted to react against the accusations so I wrote about this situation, which the lawyers advised me not to do. I posted it on my Instagram page. And it was read over 1000 times, if not 3000.

After that, these people were on the rampage and accused me of cheating on my wife and purposefully lying in my article. These are the kinds of things I sometimes have to go up against. I don't care, and this is the price I pay.

Kenny Scahchter posted the article ‘The Art of War (and War of Art)’ on his Instagram account on 12 July, explaining the situation in excruciating detail.-- Ed.note

www.instagram.com/p/CCigrZKADkR/

Honesty and courage make up the pedestal for being outspoken. Do you ever feel discouraged?

If not daily, then at least weekly I get let down, disappointed. I mean, more often it’s because of the model I have made for myself. I don't capitulate or compromise terribly often.

I get edited as well. New York Magazine once edited my work so heavily. I'll never forgive myself for not being more adamant about it.

I've spent 30 years building my audience. It is never consistent financially. It hasn't gotten easier in the course of 30 years. Never. It's still a complete hustle. The work is hard; nevertheless, my passion has never dimmed, and my faith has never relinquished.

I have one life, and it's such a short period of time. I wouldn't want to live my life just trying to make a lot of money and being able to buy more expensive cars and more expensive holidays. I don't leave for the holidays. The only holidays I ever take are in places that are in close proximity to see art or people that are engaged with art, because visual art is my only interest. I don't have hobbies other than a bit of classic cars. I love reading biographies of people who have done extraordinary things out of nothing. I have a great respect for human ingenuity. But other than that, art, art, art…

With physical spaces on lockdown, and exhibitions and sales rooms having migrated online, many people interested in art have crossed the barrier from buyer to collector thanks to digital viewing rooms.

Art is the most conservative industry I've ever faced in my entire life. The online viewing rooms are nothing more than glorified websites that are considered a breakthrough in the business of art. It's ridiculous. This year, I visited the Dallas Art Fair online. That was in March, when this whole pandemic started. I like the fact that most or many galleries list the prices in the online viewing room. But more often than not, the major galleries don't even do that. I love transparency, therefore in my writing the prices, the buyers and sellers are revealed. The art world is famous for keeping these aspects hidden like a state secret.

People have acclimated themselves towards the advent of technology in a much quicker and more overwhelming fashion than they ever did before – out of necessity. So I think that people have become much more comfortable with the online context within which to consume more. The digital experience of looking at art will never substitute the physical relationship you can have with an object unless it's artwork intended for a digital format. But I think it's very important that people are open to social media, to the digital offerings of galleries. The most incredible thing, which I just find really extraordinary, is the fact that since physical auction theaters have been shelved due to the pandemic, Sotheby's contemporary art sales, for instance, had a viewership of over a million people this autumn. I find that to be absolutely gobsmacking.

Before the pandemic, the auctions were also available online. Were those numbers any different?

True. I don't think the audience was ever more than probably between 50,000 and 200,000.

People are bored of streaming Netflix series, and they're starving for entertainment, so they watch other people spending money. I guess that constitutes a famine these days.

The cheaper art is as good as the best. People can spend $5000 impulsively, if they are wealthy, and don't worry too much about it. I just think like, in the past, nobody would even think of watching an auction online who was not professionally involved in the art world. So somehow, people caught on to the fact that auctions were free, and were duly available. And I'm not quite sure what else has sparked this trend other than the fact that people have nothing else to do.

At a time when galleries are facing uncertainty, many artists who don't have gallery representation are experiencing a boom selling works directly from their studios. It’s been amazing to see that happening.

I mean, more and more you'll see artists take a self-agency approach towards marketing their art. Like David Hammons, the great conceptual provocateur of art who put his works up for sale at Phillips in the 90s. He took this market in his own control. I mean, there's a long history of the Impressionists having no opportunities to sell their work and taking commercial matters into their own hands.

Especially during times of crisis, you have to be more proactive as an artist to figure out ways to make commerce. It's not easy in the art world or in any world. And when there's such financial hardship, and so many people who are ill and dying around us, it takes ten times more work and effort to do so.

Little by little, banks and companies like Deutsche Bank and British Airways were silently selling their corporate art collections. Is this an act of financial desperation?

Art has become monetised over the last 25, even 250 years. Not that I said that – Renaissance painters were infatuated and obsessed with money in the same way artists are today, except the audience for art has grown exponentially through things like social media and larger global participation in the market. That's why it's always depressing to hear politicians dismiss globalisation as some kind of bad force, which is absurd. Globalisation is the most beautiful aspect of the old world – that people can communicate from every continent and from all economic walks of life. And I think that's a beautiful, significant aspect of what makes our world such a special place to live in.

When you have an art collection that you bought as a company 20 years ago to beautify your office space and make it more attractive to your clients, and all of a sudden, this art that you once bought for $20,000 or $50,000 is now worth $400,000, you have a responsibility to your shareholders to sell that art. It is totally understandable if a company can sell an art collection and fire one less person at the expense of an artwork. The company has no responsibility to the public to have a nice painting on the wall, but a museum does.

Because we're in such, you know, an unorthodox situation like a global epidemic, museums selling parts of their collection should be only an emergency situation.

I mean, the Baltimore Museum of Art was about to sell three major paintings from its collection. (A Sotheby’s sale of works by Brice Marden, Clyfford Still and Andy Warhol was estimated to bring in $65 million to fund acquisitions of art by people of colour and staff-wide salary increases – Ed.note) And literally one or two hours before the auction, they were forced to pull the works from the sale because of the public outcry – which is a great characteristic of the social world of today, in which enough people can band together to express displeasure at a travesty like a museum selling works.

How much time do you spend on social media?

I was addicted to Facebook for ten years after my kids unwittingly signed me up back in 2008. Facebook is a more ‘socialistic’ platform – active users are aware of important social problems. Once I got into a month-long battle with British art critic Matthew Collings, which was frustrating. It was like arguing with a brick. You couldn't talk to him in a way that would make him acknowledge something that was already established. He started making personal, stupid, frivolous comments to me. Then I just get bored of Facebook. Don't get me wrong, I like to get into discussions (chuckles). I have studied philosophy, law and political science. I think it's fun to have a position, an opinion, and stand up for it.

I use Twitter sporadically. I don't think in fragments that are 140 characters long. So as long as I can write in long form, Instagram is pretty much the only social media that I'm actively on with great care and thought engaging. I wish it would be a little more like Facebook and open-ended towards discourse amongst people. But nevertheless, Instagram just suits me perfectly right now. Everyday there are more ads; sooner or later it's going to bug the shit out of me and I'm just going to move on to something else – the same way I don't get attached to one art piece or another. I'm just reminding myself to archive the content of my Instagram account. I would be sad if I lost that. But in the end, my articles are what counts. My artwork is what counts, and I will always exist no matter what.

Social media is very much a real-life give-and-take experience for me. It has revolutionised visual communication and expression. I have established means of communication with people from all walks of life – rich people, poor people. I opened myself up to people that are starting out in the art field. I interact with people from every region of the globe in a very personal way. On Instagram I discovered this brilliant emerging painter in her mid-60s, and we established one of the strongest artists relationships I have. And we've changed each other's lives.

I'm back from Kenny Schachter on Vimeo.

What do you think of art meme culture? Do you smirk at them in secret?

I mean, I like humour, but 90% of the art memes I don't even find funny.

Funny is funny, no matter what form it takes. Artists like Maurizio Cattelan use humour as part of the basis of their art. I wouldn't call it a meme. I make these short narrative video art films, or for lack of a better term, short digital films. I don't really care what you call it.

There is this one meme site where the person behind it banned me because I revealed her identity. And then she went on to accuse me of engaging in gross behavior. And I've never even met her – nor do I want to.

Schacter's article on revealing Hilde Lyn Helphenstein as the creator and true identity behind the Instagram account Jerry Gogosian – Ed. note.

news.artnet.com/opinion/kenny-schachter-on-frieze-los-angeles-2020-1784211

I just think memes are a little bit shallow. I love art that cheeks art. I love art that's about philosophy. I consider art to be giving physical form to thoughts, ideas and concepts. And humour is very much a part of my life as a defense mechanism, but mostly as a celebration of humanity through what is funny. So I don't really like these accounts, whether it’s Jerry Gogosian or The Art Gorgeous. Nevertheless, l like how the founder of the platform The Art Gorgeous interviews people.

Balcony Naked © Kenny Schachter

Is there something you would like to highlight as having been particularly positive in the art world this year?

I'm not going to say if it is negative or positive, but, I mean, people consume art through art fairs, primarily. In 2000 there were 50 art fairs, whereas now there are around 300. The onset of COVID19 and global travelling coming to a near standstill has resulted in the degree of people frequenting art galleries accelerating in proportion. Local gallery scenes have benefited, more or less, as a result of the cessation of art fairs. I admit that I didn't visit as many galleries as I would have hoped to in my first year of living in New York City. I had COVID19, so I couldn't go out for three weeks. Still, I’ve gotten to see twice as many galleries as last year.

I used to travel every two to three weeks for the last ten years, non-stop. This year I spent more time just luxuriating. With that said, I don't mean the typical notion of luxury, like running expensive, but the opposite. Luxury, for me, was having the time to appreciate the things that surrounded me in a much more meaningful, intimate fashion.

Thank you for this private lecture.

That's what I'm here (on this planet) for.

Read Kenny Schacher's articles, acquire author's books, and other products on www.kennyschachter.art

Title image: Death be not proud (it is bound to happen soon er or later) Video still © Kenny Schachter