On trees and people

11/09/2019

You can't deny the surrealness of sitting in a 32,000-seat stadium that is usually filled with an adrenaline-fueled football game, looking at a forest that for two months has occupied the pitch like an alien from outer space. Instead of adrenaline, one senses a strange feeling of all-encompassing peace. In place of tense excitement, there is contemplation. Instead of often misguided passion, there is poetic conception. And instead of the collective roar of shouting for one’s team until hoarse, there is a spatial silence. Because as we all know, in the forest one doesn’t shout – one listens.

The forest that has taken over the middle of Klagenfurt's Wörthersee Stadium for two months – the art project FOR FOREST – The Unending Attraction of Nature (9 September - 27 October) – is undeniably beautiful despite its absolutely absurd location. And that is precisely why it is so significant – the inherent contradiction of the project is its main feature!

Klaus Littmann „FOR FOREST - The Unending Attraction of Nature“, Art Intervention 2019, Wörthersee Stadium Klagenfurt, Austria. Photo: Gerhard Maurer

FOR FOREST is a story about the forest and people, and the times that we live in...with all of the nuanced relationships therein and their inherent contradictions. It embodies ambitious feats of engineering while, at the same time, encourages us to let go of ‘the ego’ and our pretentious self-proclaimed status of ‘lord of creation’ in terms of the natural world. As Arterritory.com has already reported, FOR FOREST is the lifelong project by Swiss curator and artist Klaus Littmann that began thirty years ago after he saw the dystopian drawing The Unending Attraction of Nature by Austrian artist and architect Max Peintner (b.1937).

As Klaus Littmann mentioned at the project opening’s press conference last Thursday, the portentous drawing was shown to him by a friend. And even though he really wanted to buy it, it had already been sold to a US collection by that time. ‘There was nothing left for me but to turn this idea into reality,’ Littmann said. He also emphasised the contextual nature of the project, more or less also serving as an urban reality alarm bell as the forests of the Amazon and Siberia smolder and burn. ‘It is important to plant forests. This is not just an art project but also a social project.’ It should be noted that this is not Littmann’s first project linked to football and stadiums: in 2003, Littmann Kulturprojekte in Basel organised the exhibition The Stadium: A Cult Venue, the subject matter of which was the excesses that take place during football games.

„FOR FOREST - The Unending Attraction of Nature“, Art Intervention 2019, Wörthersee Stadium Klagenfurt, Austria. Photo: Una Meistere

Undoubtedly, the controversial aspect of the project is the fact that it is located in Klagenfurt, a city surrounded by nature and whose skyline is marked by mountain ridges...not to mention the real and verdant forest growing about a five-minute drive from the stadium. If this ‘art intervention’ had taken place in an abandoned stadium in the Amazon or Siberia, or even in the middle of a desert, it would have had a completely different gravitas and impact. Be that as it may, c’est la vie – Klagenfurt turned out to be the great ‘opportunity of a lifetime’ for this project, in effect becoming both a springboard and a handicap.

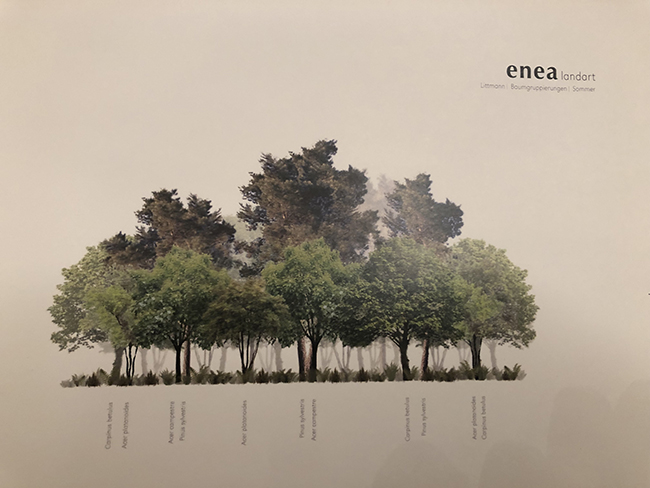

At the FOR FOREST press conference, it was repeatedly stressed that the project did not use taxpayers' money and was carried out with the support of private donors. The trees, in turn, were provided by nurseries in Germany, France and Austria where they are grown for cultivation and replanted every three years. These trees are used by landscape architects for urban landscaping, and their root systems have been specifically adapted for such an existence; in essence, all sustainability criteria have been fully met in the realisation of the artwork. In addition, the landscape architect Enzo Enea, who collaborated on the project, set the condition that the 300-tree artificially mixed forest of birch, ash, oak, white willow, pine, etc. would subsequently be transplanted as a whole to the outskirts of Klagenfurt, where it will continue to live out its now-authentic forest life as it develops into a natural forest ecosystem. Enea has said that the main challenge in executing the FOR FOREST project was the forest itself, i.e. its size. ‘Dimension is always important. The average footballer has a height of 1.80 m, and it was important to me how each tree would look in the context of the stadium.’ Enea settled on an average height of 15 m for the trees, which, one must say, perfectly fit into this absurd venue.

Klaus Littmann „FOR FOREST - The Unending Attraction of Nature“, Art Intervention 2019, Wörthersee Stadium Klagenfurt, Austria. Photo: Gerhard Maurer

Littmann does not hide the fact that from an architectural point of view, Wörthersee Stadium is the ideal platform for executing the installation – the contrast between the concrete, glass and trees is very stark. ‘It encourages you to think about your relationship with nature in a very personal way.’ Yet at the same time, hidden beneath it is the obvious paradox of investing large amounts of money and effort into planting an artificial forest in a stadium, all for the purpose of encouraging people to think about what is happening in the nearby real forest...and with world ecology overall. According to landscape architect Enzo Enea, this is precisely the purpose of the project: ‘It is artificial. It creates an impact over a short period of time. Of course, it is paradoxical. But I think it is time that we do something so paradoxical that it switches the way our brains think a little bit. We have to turn things around now – that's the whole point.’

Klaus Littmann „FOR FOREST - The Unending Attraction of Nature“, Art Intervention 2019, Wörthersee Stadium Klagenfurt, Austria. Photo: Gerhard Maurer

When asked if he thinks art has the power to change people, and whether this is the right way to do it, Enea answers: ‘It is never to late for human beings to do something, but only as long as you actually do something. I think that for me, all art has to have a reason or something behind it. Otherwise there is no sense in doing it. Whatever you try to say, the message should arrive somewhere. When I go to a museum, I always see a lot of things, but there are just certain paintings and sculptures that touch me… if it touches me, it moves me somehow, and this is what I want from art. If people come and realise that they are looking at a real forest in an artificial place, it could move them. At least I hope it does. The forest has been removed from its normal living space. I think it is important that people just sit down and reflect on this. This contrast is very important because when people think of the forest, they think everything is normal – everything is as it should be. For example, for me it is a normal thing to go out and into a park because I grew up doing that, and it is a completely normal thing to have a park in which to go. But when you go for a walk in the woods, you usually don’t think about what is going on with the forest itself. Does it get enough water? Sometimes you see a dead tree, and you have no idea what happened to it, but you just ignore it and go on. What we wanted to do with FOR FOREST is give people a sense of what could happen and what is happening to the forest at this moment in time. We are killing biodiversity with monocultures, the soil is being poisoned, bees and butterflies are already disappearing from many places, and so on. If we continue like this, all that will be left of nature will be a zoo. You’ll have to go to the zoo to look at a forest.’

Klaus Littmann „FOR FOREST - The Unending Attraction of Nature“, Art Intervention 2019, Wörthersee Stadium Klagenfurt, Austria. Photo: UNIMO

To further magnify the complex context of human-nature relationships, the forest installation can only be viewed from the spectator stands. You cannot enter it, wander around in it, get lost in it, or walk down its paths. You are not allowed to experience the smell of a sun-heated or rain-soaked forest, nor may you lean against the trunk of a tree trunk and check to see if there really are any birds living in it. In its own manner, the stadium seemingly guards the forest while, at the same time, emphasizing the chasm that has developed between nature and people.