The conductor of an orchestra of artist jewellery

An interview with legendary jewellery maker GianCarlo Montebello, who gave rise to a new movement in art in the 1960s – jewellery created by fine artists

19/07/2016

GianCarlo Montebello and Teresa Pomodoro are a legend of Italian jewellery and, in a sense, also a legend of the entire art scene of the second half of the 20th century. In the 1960s they launched a unique movement in jewellery, namely, limited-edition jewellery made by fine artists, and in 1967 Montebello together with his wife Teresa (sister of the Italian sculptors Arnaldo and Giò Pomodoro) founded the companyGem Montebello, which supervised the manufacture of the jewellery. Thus, the project became an experimental, and sometimes even overtly sentimental, sidestep in the creative biographies of many a classic 20th-century artist.

But we must remember that the 1960s were a special time for jewellery, when practically all existing paradigms of the fashion and jewellery industries were shaken up with a hurricane-like force. Even though many of the well-known jewellery houses upheld the classical traditions and continued to work with precious metals, a radically new direction entered the scene as well, namely, conceptual jewellery based on experiments with completely new styles and materials. By this time, new introductions, such as plastic, mixed metals, paper, rubber, natural materials and even fabric, allowed gentler and more plastic forms than standard metals. From serving simply as decoration and beautiful accessories, jewellery grew into an endless embodiment of creative fantasy – a challenge, sometimes even a provocation, a social declaration that for a while pushed the conditionally practical and commercial aspects of jewellery into the background. In addition, the new jewellery began to be made from materials whose value was, according to classic standards, laughingly low, thereby challenging the concept of “status symbol” and other such primadonnas of the social scene.

During our conversation, however, Montebello admits that not all of the artists he invited to create jewellery agreed to the project, because some of them still considered jewellery as something elite and a part of the bourgeois lifestyle – everything the 1960s were against.

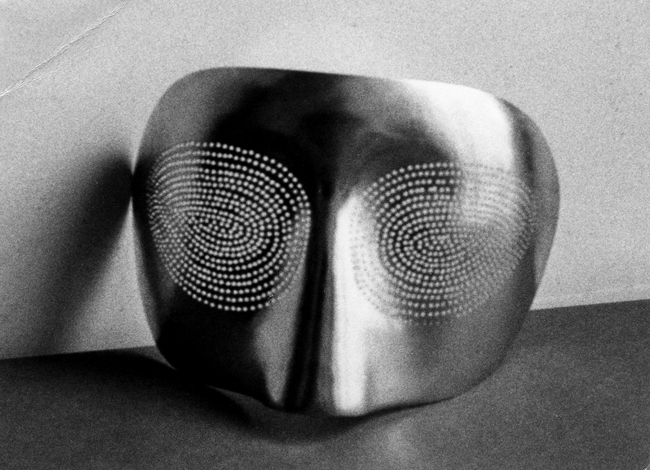

From the very beginning, Montebello enjoyed the closest collaboration with the classic surrealist Man Ray. This collaboration resulted in a total of eight pieces of jewellery, including the now iconic Optic-Topic gold mask (1972), of which 100 copies were made. Montebello still has one of them in his workshop. Man Ray also created the Pendants Pending earrings (1970) in his famous spiral-shaped lamp shade form. Because of the earrings’ weight, a special mechanism was created that allows the earring to be placed around the ear instead of hung from the earlobe as traditional earrings. But Montebello avoids answering the question of who came up with such a solution. In any case, the earrings became famous after being worn by French diva Catherine Deneuve.

Man Ray. Mask Optic-Topic realized in sterling silver gold plated. Project of 1974 made in 1978. Editions of 100, numbered and signed. Photo: Giorgio Boschetti

In all, Montebello collaborated with over 50 artists between 1967 and 1978: César, Sonia Delaunay, Piero Dorazio, Lucio Fontana, Hans Richter, Larry Rivers, Niki de Saint Phalle, Jesús Soto, Alex Katz and others. In addition to the creative challenge, he always also stressed the “informative nature” of the collaborations, meaning that jewellery became a way in which the broader public was introduced to the art scene of its time. Released in limited editions, the jewellery was not positioned as works of art and was therefore sold for very reasonable prices. Montebello still has a price list from those days on which we can see that some of the jewellery did not cost more than 210 Italian liras. Of course, today these very same pieces have gained a different status and fetch ever more astronomical prices at auction, because there are only a few copies available of each piece of jewellery, and these have all become coveted collectors’ items.

In 1978 Montebello’s workshop was broken into by thieves, and he subsequently brought this episode in his life to an end. He thereafter concentrated on developing his own collection, calling his jewellery “body ornaments”. He rarely collaborates with artists anymore, because, as he says, the style of collaboration has changed along with the times. Whereas private conversations were a natural part of the process in the 1960s and 1970s, nowadays there’s a sea of assistants one has to deal with....

Interestingly, Montebello personally owns very little of the jewellery dating to the late 1960s and 1970s, and he’s even tried to buy back some of his work from art collectors. He has a particularly close professional relationship with Diane Venet, a French art collector who was one of the first to begin collecting artist jewellery, thereby also creating a market for it.

I met Venet last year in New York, in the workshop of her husband, French sculptor Bernar Venet. In fact, our conversation led me to look up Montebello. After meeting Montebello, I asked Venet to describe him: “For me, he is the father of this whole movement. He was the first to encourage his artist friends to try their hand at designing jewellery. And also, their collaborations were very close. They had unending conversations – he dug deeply, so that the jewellery designs became something like a continuation of their art. Only someone who passionately loves his own craft and art can do that.”

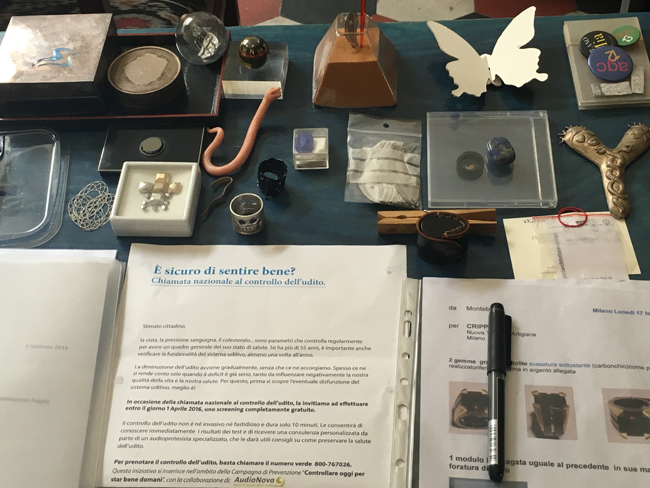

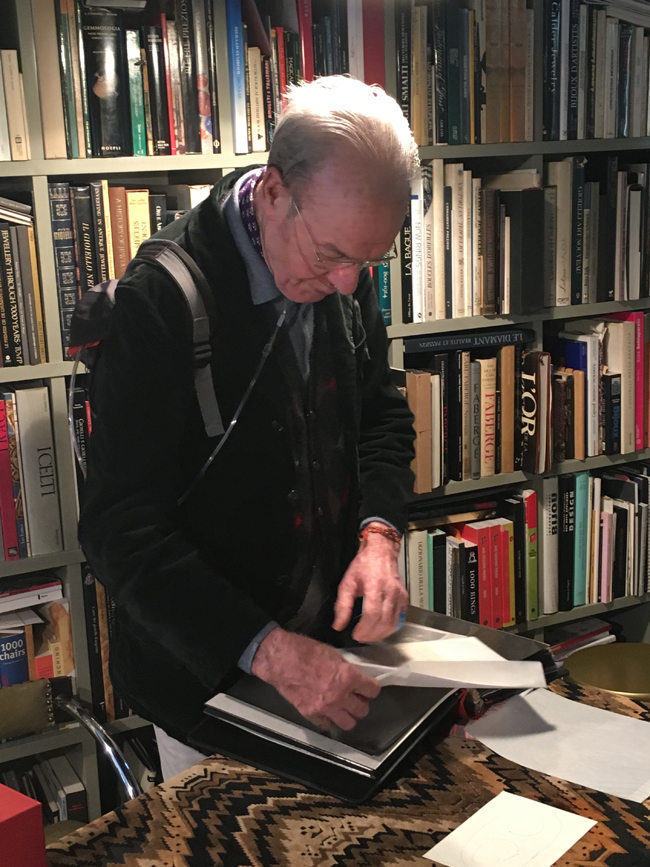

Studio of GianCarlo Montebello. Photo:

My conversation with Montebello took place in Milan, in his workshop, which is also his residence. It is located in Milan’s Chinese quarter – a place that, I must admit, I did not know about before. Montebello is now well over 70 years old, and most of the great 20th-century artists he worked with have long since passed away. While we speak, I continually have the feeling that I’m in the presence of a whole century of art history, in the presence of a person who has seen with his own eyes that which the rest of us only read about in history books. With slightly shaky yet precise jeweller’s hands, one by one he pulls folders from the archive he keeps in a large bookshelf. There, protected from dust in plastic archival folders and tissue paper, we find sketches of jewellery by Man Ray and other artists. Each sketch contains a story. On the table is an ashtray designed by Man Ray – he couldn’t stand the smell of a regularly snuffed-out cigarette, so he designed an ashtray with special holes that cut off the end of a finished cigarette and trap the unpleasant smell inside.

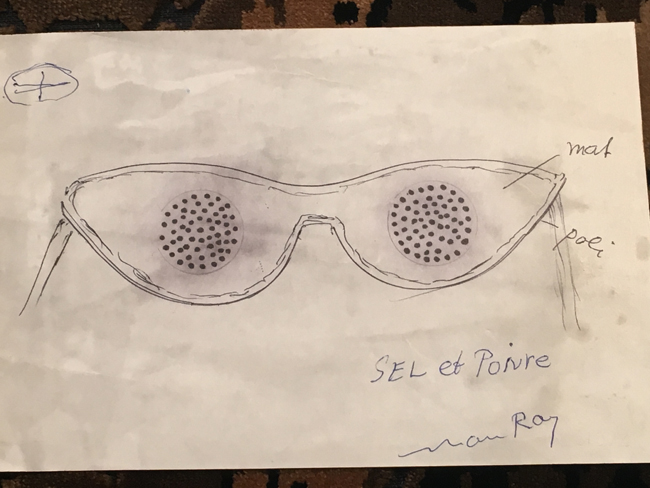

Man Ray's sketch for the Salt and Peper glasses. Photo from GianCarlo Montebello's archive. Photo:

Please tell a bit about how the idea for Gem Montebello began. Was it you who approached the artists, and who were the first artists you turned to?

In 1967, I first approached artists I had met before and who were close to me: Lucio Fontana, Arnaldo and Giò Pomodoro, Consagra and Piero Dorazio. This was during 1967. Then later I started working with other European and American artists.

I know that you had a very special professional relationship with Man Ray.

Yes. That was later in my artistic career, in the 1970s.

One of the most special pieces of jewellery you created together with Man Ray was the gold mask, although originally it started out as eyeglasses.

The mask was made quite at the end. We started with another kind of jewellery, and the mask was made at the end. But then, unfortunately, Man Ray died. Anyway, the mask was a wearable object – he didn’t want to make anything just to be hung on the wall.

At the very beginning, Man Ray sketched some glasses that were to be made entirely in gold. This was the initial project, and he wanted that the glasses have very small hinges. The shape was very “glamourous”, because Juliette, his wife, was American and the glasses were intended for her, so the piece had to be with a glamorous shape but with quite invisible hinges.

Man Ray named this pair of glasses Sel et Poivre (Salt and Pepper) because the lenses were made entirely in perforated gold, and this, in his Surrealist and Dadaist spirit, was the right name. It seems quite strange, but, once worn, the view is perfect and one’s sight is protected. The idea of perforated lenses came to Man Ray because he loved sports cars. At that time, all sport cars were convertibles, and drivers had to wear special glasses in order to protect their eyes. Those special goggles were made of aluminium, and the lenses were perforated in order to safeguard the driver’s eyes against insects and mosquitoes. So, the idea of perforated lenses came from sports-car drivers.

Man Ray's wife Juliet tries on Salt and Peper glasses. Photo from GianCarlo Montebello's archive

When the prototype was ready, I was busy and couldn’t go to Paris myself to deliver it to Man Ray, so I asked a close friend to bring it to him. Man Ray received the prototype glasses and gave them to Juliette, who wore them and they made a Polaroid photo. Then Juliette’s friend put the glasses on, and at that precise moment they broke. This occurred because the glasses – which were made of gold – were heavy, but the hinges were small and extremely delicate and didn’t work properly. Man Ray solved the problem immediately. You know, as a photographer he knew how to deal with that kind of situation. So, he dismantled the glasses and removed the lenses; he cut out a piece of black fabric, cut out an oval, inserted the lenses, and the mask was done…and he gave it to Juliette. But this was Man Ray, who lived in an art studio and lived his life as a work of art.

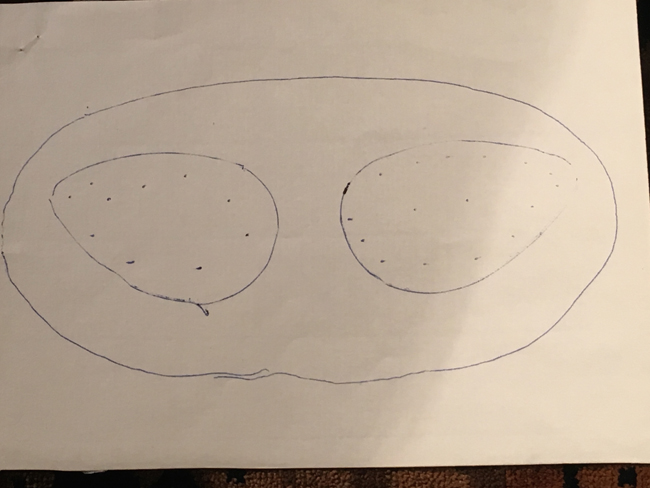

After that Man Ray wrote to me about what had happened. He took a Polaroid of the result and…instead of a pair a glasses, a mask came out. Then I made my choice: Man Ray sent me only a sketch, and I opted for the classical Venetian mask, with the nose….

At that time only one hundred pieces were made, so there were (are) one hundred people who have this mask.

Man Ray's sketch for the Optic-Topic . Photo from GianCarlo Montebello's archive.

Are they still around somewhere?

Yes, sometimes the masks appear at auctions, as it nowadays happens with artist jewellery. Sometimes the pieces appear at auctions because the previous owner has passed away and, due to the increasing value of the pieces…maybe this is too much for the heirs.

As a jeweller, what interested you most in this process of turning the sometimes wildest ideas of artists into jewellery?

Pleasure. Curiosity. At that time it was interesting to ask artists to make jewellery – not those who had already made pieces for themselves, but those who had never made jewellery before. It was also a way to earn some money. During the 1960s and 1970s things were very hard because of the “contestazione” (protests); those were years of protest, and making jewellery was considered “borghese”, bourgeois. Of course, not all of the artists responded to the invitation – some were categorically opposed to it – but many others gladly participated.

Pol Bury and Jesús Rafael Soto, the kinetic artist, they accepted because they liked the idea and they wanted to give the pieces as gifts to their wives or fiancées.

GianCarlo Montebello

Looking back at the history of artist jewellery, much of it is very private and associated with personal, even quite intimate, episodes of their lives.

Earlier, artists who made jewellery made only signed and limited editions or unique pieces. The aim of Gem Montebello was completely different – instead of using precious materials, we opted for using mixed and heterogeneous materials in order to make affordably priced design pieces and address people who possibly didn’t know anything about them before. It was a kind of “informative mission”. The pieces were not signed or numbered, because our intention was to be “informative”. And this motivation was accepted…and it was a success.

Once finished, a small card with the name of the artist and the number of pieces that had been produced was given along with each piece. The name of the artist was on the card, not on the piece of jewellery. Only the artist’s initials appeared on the jewellery. For example, LF was for Lucio Fontana.

But today this jewellery is sold at auction for great amounts of money.

Yes, because time increases the value, and things have a different price at auctions.

Only in the later years did Gem Montebello offer artists the possibility of making something with precious materials, but these were small, limited editions.

Who had the final decision regarding the choice of materials?

There was always a dialogue. Sometimes the artist asked and proposed to use a special kind of material, and at that point I suggested which was the best material to use and which technique was the best for the kind of jewellery they had in mind. There was knowledge, but also interpretation. And this is why there was no “standard edition” at Gem Montebello, because each piece was discussed and interpreted individually.

Talking about the pieces, one important thing to remember is the fact that there was never a standard situation. I was like a conductor in an orchestra – I had to be the interpreter of the artist’s idea, and I had to put the idea, the spirit, the concept of the artist in a piece of jewellery. What I had to do was instil and maintain the spirit of the artist in the jewellery through the technical skills of a goldsmith; the jewellery became a representation of the feeling, the concept and the idea of the artist. And that was the difference between jewellery by Gem Montebello and that of others, because each piece was the complete representation of that artist’s feeling.

How do you yourself classify these pieces of jewellery – are they works of art (because they’re based on the artist’s idea), or are they functional decorative objects?

Some were like “reductions” of works of art; many times they assumed the well-defined character of the artist, even if they were small in size.

One thing to remember is that the artists never asked themselves if the jewellery they created was beautiful or if they were making something beautiful – they used a woman’s body as a moving space, a moving wall upon which to exhibit their works.

Niki de Saint Phalle. Necklace Mouth and Eyes yellow gold, both side enamelled in various colors. From a drawing of 1973,edition of 12, numbered and signed. Photo: Antonia Mulas

You collaborated with Niki de Saint Phalle. Was her approach to jewellery, as a woman, different from that of male artists?

Niki loved jewellery very much, and what she loved most was to offer them as gifts to her friends. Each piece was made in gold and enamel. All of her works were lacquered in different colours. There was a lot of work to do: engraving, enamelling….

Were there any ideas over the years that turned out to be impossible to transform into the language of jewellery?

No, because the artists who weren’t interested in this project simply said “no”, and I always worked with those who wanted to make jewellery.

Jewellery has always had a very special relationship to the human body. How important was this aspect to you, as a jeweller, in your collaboration with the artists?

Very important. What you had in front of you was the artist, but behind him were my goldsmiths and I. We were concentrated on wearability and all those technical skills and aspects that the artists sometimes did not consider – the jewellery was sometimes not well-refined in certain points of view, like wearability, for instance. And I was there for this. I took care of all the technical aspects about making a piece of jewellery, because they had to be well-refined.

After your workshop was burglarised in 1978, you announced that you would stop making artist jewellery. Why did you decide to do that?

It was a “suspension” because of the theft. I decided to stop for a while, not to close completely, but I decided for a “suspension”. Then I began making jewellery again with the exhibition “Italian Metamorphosis 1943-1968” curated by Germano Celant in 1994 at the Guggenheim Museum in New York.

And then Niki de Saint Phalle called me. Some people had asked her to make some jewellery, and she accepted only under the condition that she could work together with me.

But from that moment on things, and the art world in general, changed completely; the feeling was completely different from the scene of 1960s Paris, for example. I worked in Paris with Soto, Bury, Man Ray, Niki de Saint Phalle...and if I think, for example, of Lucio Fontana – the approach and everything was very “easy” and friendly at that time. Now it’s different – the spirit today is totally changed, and it’s all a financial adventure.

What do you think changed the art world?

Art has been absorbed by finance, it’s a business. Art is no longer independent, it is considered as merchandise, as a business. Prices increase, prices are high in galleries and at auctions.

GianCarlo Montebello by his archive. Photo:

Do you still collaborate with artists?

Yes, but I collaborate with just a few artists, not as before. I prefer to remain in the background. My last collaboration was with Günther Uecker (he is now 80 years old), and I also made a series of pieces with [architect and designer] Andrea Branzi.

You first studied interior design and only later turned your attention to jewellery. Why?

I did my apprenticeship in various architecture studios, and I worked in what at the time was called in Italian “arredamento”, which then became “interior design”. At that time, the world of architecture and “interior design/arredamento” was really closely linked with artists, and I always loved details: this is the right way, this is the correct dimension, and so on.

I read that this attention to detail was also one of the reasons why you began making jewellery. Is that so?

I always loved experimentation, and luckily I worked with open-minded people, but I always had this attitude for details. Everything is made of and by details.

For example, if one looks at Carlo Scarpa’s buildings, especially the Olivetti shop in Venice (now the property of FAI, a heritage foundation) or the Fondazione Querini Stampalia in Venice or the Museo di Castelvecchio in Verona, one will always detect a strong impact on dimensions, but not an overwhelming one. That is something that touches a person deeply. Well, this dimension is made of details. The materials, for example, and how they were carefully chosen. It’s very difficult to explain, but Scarpa had such care for every detail.

Is jewellery a kind of language, an instrument of communication? Sort of like an extension of the personality?

Sure. We can see it immediately. It’s an extension.

Shoe laces. The only men accessory created by GianCarlo Montebello

Did you ever wear the jewellery you created?

No, because I never made jewellery for men. I made only shoestrings – I’ve never designed anything for myself except the shoestring in 1981. It was an ornament, in a way, that had a function. But I have to say that in 1981, when everybody had similar shoestrings, mine were different, shoestrings with diamonds for my tuxedo.

I can imagine men’s jewellery, but in my opinion everything has to be functional. For example, sometimes I use cufflinks as fasteners for necklaces and bracelets.

How do you feel about contemporary jewellery? In which direction is it going now? It seems that all taboos are gone nowadays....

I see everything as a process of evolution. The important aspect is to be “honest”. I see every change in contemporary jewellery as an evolution, but it has to be honest and sincere. I do not like all this jewellery made “for fashion”, because you have to be able to feel and see the quality. And quality is strictly connected to honesty, it’s a sort of reflection of honesty.

Just for example, I remember an exhibition, thirty years ago in Switzerland, by a Swiss jewellery artist who works only with paper. There was such care for the material, and that immediately gave the works a special quality.

But what is happening today is very interesting.

Lowell Nesbitt. Brooch or necklace Lily, entirely enamelled and miniated on yellow gold chiseled. Movable pistils. Chiseled collar shaped with two leaves. From a drawing of 1972. Edition of 5, each of a different colors, numbered and signed. Photo: Antonia Mulas

And yet, people have always been fascinated by gemstones. Have you, as a jeweller, understood why this is so?

To me, most of the time they’re nothing but wasted materials. All these brands, like Tiffany and Cartier, they’ve lost the ability to make something different. They use too many stones – not because it corresponds to their classic tradition of making jewellery, but because they have lost a sense of proportion. Instead of making something truly good and different.

On the contrary, if I think about the Chinese shop near my studio that sells big, fake jewels…yes, on the one hand they are terrible, but they’re also fun at the same time, and they’ve got some very creative pieces….

All these big brands, there is such an arrogance in them, only because they are a “griffe”, a brand. For example, Chanel jewellery. What do you think of it?

Well, Chanel’s artificial pearls were a quite revolutionary idea for their time. Today, of course, they’ve become simply expensive brand-name imitation jewellery.

Chanel invented what we call “the bijou” – not the real jewel, but the fake one. Because at that time, she was a young and beautiful woman and she received amazing jewels as gifts. Then she said to herself, “I would like that every woman could have such jewels as mine”…and she invented the so-called “bijou”. But we have to remember that Fulco di Verdura, who was a prince, designed jewels for her.

Is jewellery connected with the time in which it was created, or it is timeless?

Some pieces represent their time; others are for ever. As in art, there are some artists (very few) who transcend their time. Lucio Fontana, for example. Lucio Fontana is always the Future.

Lowell Nesbitt. Brooch or necklace Lily, entirely enamelled and miniated on yellow gold chiseled. Movable pistils. Chiseled collar shaped with two leaves. From a drawing of 1972. Edition of 5, each of a different colors, numbered and signed. Photo: Giorgio Boschetti

Can you name three pieces of jewellery that were made in collaboration with artists that you consider your masterpieces?

The first piece is the Lilium (Lily) by Lowell Nesbitt. It was made in 1972 and is a piece between pop culture and hyper-realism. “Pop” was the size – very big – and hyper-realistic because the work was entirely realised with the bas relief technique, then illuminated and enamelled. Each part of the piece – which can be both collar and brooch – was deeply studied in every detail. The flower’s styles and pistils were all movable. It involved a great amount of work, and so we made only five pieces of the Lily. The gold it was made of had to go in and out of the oven at high temperature and was extremely “stressed”, because it had to also be engraved, enamelled, illuminated….

The second piece is Optic-Topic, the mask by Man Ray, because it is so…Dada!!! And above all, for the history behind the piece. The main lesson of Man Ray is that sometimes what appears to you is not what you see. What you see is something else and not what stands in front of your eyes.

Read in the Archive: An interview with French artist jewellery collector Diane Venet

Another piece was one we made at the very beginning of Gem Montebello – a piece by Giò Pomodoro, made in silver, with a small sphere. This piece conveys a great power, it has great impact due only to its inner simplicity. This piece was made with only half a gram of gold. It has a simplicity and a lightness like a fresh flower just picked in the garden. It has such an inner freshness. And it still has great power because of its simplicity.

And then there is the Eyes Lips necklace by Niki de Saint Phalle, which is currently in Diane Venet’s collection. It creates a very surreal impression when wearing it – you have your own eyes and lips...and then there’s what seems like a reflection of them in the necklace. In addition, it’s very precise and lies symmetrically on the neck, thereby enhancing the surreal effect even more.

Box for Lily. Wood, gold leaf covered, hand painted inside. Photo: Giorgio Boschetti

Translated from Italian to English by Nichka Marobin