Looking Westward: Lithuanian Architects During the Soviet Era

Roslyn Bernstein*

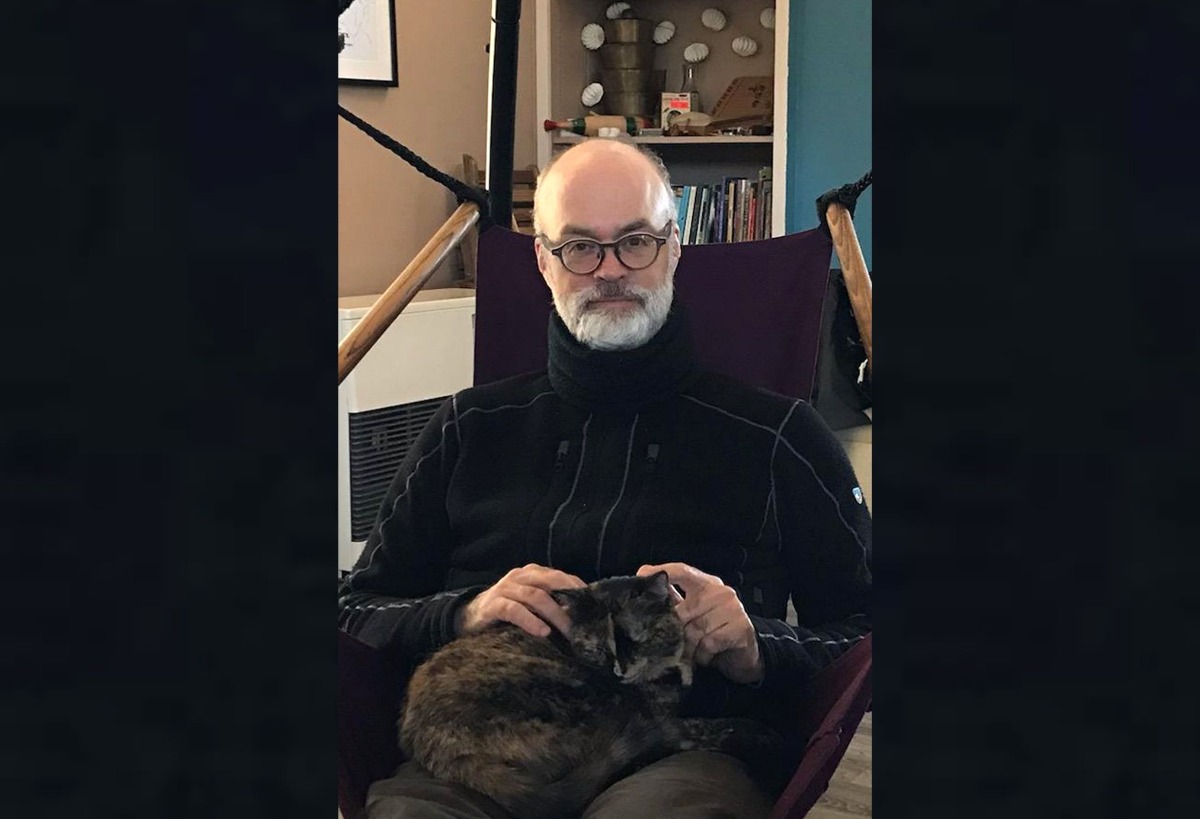

An interview with architectural historian John Maciuika, Professor of Art and Architectural History at Baruch College, City University of New York and Affiliated Faculty Member, the CUNY Graduate Center

Architectural historian John V. Maciuika specializes in the history of architecture and design from 1750 to the present. He teaches art history survey courses and advanced undergraduate and graduate courses on the history of architecture, urbanism, design, and the applied arts at both Baruch College’s Department of Fine and Performing Arts, and at the CUNY Graduate Center’s PhD Program in Art History. His research emphasizes the relationship between architecture and cultural identity in Germany, Austria, the former Soviet Union, and the Baltic States. Professor Maciuika is also interested in such issues as architectural and digital humanities in the twenty-first century.

Maciuika’s book Lithuanian Architects Assess the Soviet Era (based on the 1992 Oral History Project), edited with Marija Dremaite (to whom this interview is dedicated), was recently published.

Tell me a little bit about your family background. I know that you were born in the US to Lithuanian parents who emigrated to escape the ravages of the Second World War.

The Baltic States were one of the few places that had the dubious honor of being occupied by both Stalin and Hitler at different times. During the time when the Russian forces were driving the Nazis back and the German army was in retreat, people who were in the educated middle-class believed that they were going to fare very, very poorly under the Soviets. Many of these families, including ours, had already had members deported to Siberian concentration camps. So, it was very clear that the strategy was not only to flee, but to try to flee westward and to keep going until you ended up in a part of Germany that was occupied by either the British or American army, because you would fare much better under those occupation armies then you would under the Soviets or the Germans. My family was part of that diaspora of Lithuanians. Nowadays, there’s about 3.5 million Lithuanians living in Lithuania and about 1 million Lithuanians living elsewhere around the world.

Talk about your parents’ return visit to Lithuania and your first trip there in 1980.

My parents were allowed to visit by the Soviets in 1971. My father immediately went and reconnected with my uncle, his younger brother, who had been sent to Siberia at age 15 for fighting with the partisans against the occupying Soviet army. Both of them had heard through different channels that the other one had died. In 1980, when I was 14 years old, I traveled with Intourist, the official Soviet tourist agency which everyone knew was basically connected with the KGB secret service. Our guide was a lovely 30-year-old woman named Nijole who had to report on every single one of us. We were supposed to follow the rules and were not allowed to go anywhere without the group and supervision – although we did duck out of our hotels at night to visit relatives on my mom’s side and my dad’s side.

You did not return to Lithuania until a decade later, when you were studying for your PhD in Architectural History at Berkeley. At that time, was there any coursework on Russian architecture or on the Baltic region?

That’s a really good question. When I started, it was the fall of 1991, and of course the wall had fallen in Berlin and the Soviet Union was falling apart. At the forefront of the movement to secede from the Soviet Union was the small Baltic country of Lithuania. They were, in many ways, leading the charge, and had the distinction of being invaded by Soviet tanks – 13 civilians died in a protest on January 10, 1990. It was the day after the Americans invaded Iraq in the first Iraq War, but there never was any news on their deaths because the media were too busy reporting on George Bush and Iraq.

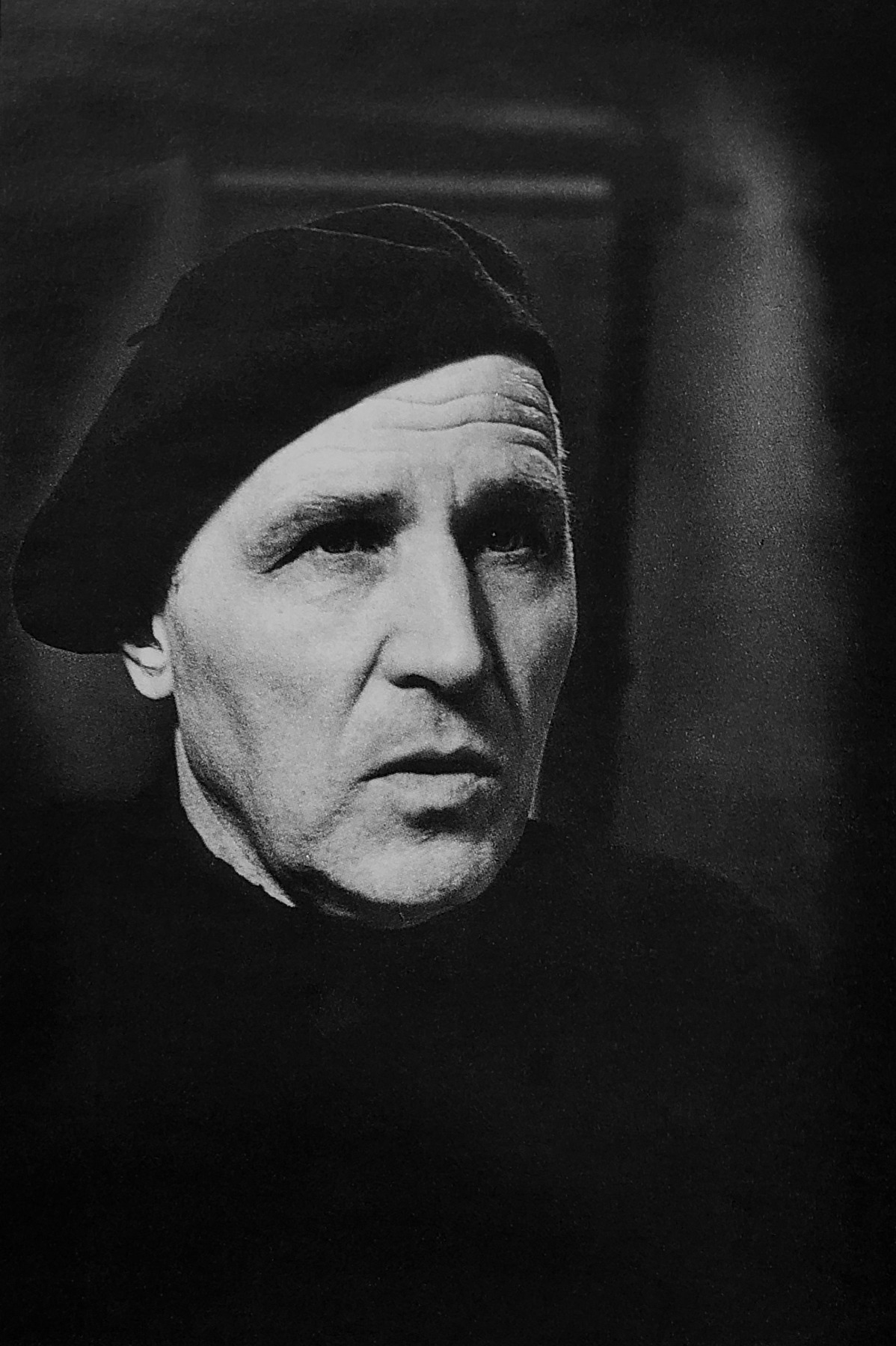

Photograph of the sculptor Vytautas Maciuika (1930-1999), in Vilnius in 1982. Uncle of John V. Maciuika, Vytautas Maciuika was instrumental in arranging interviews with four of post-Soviet Lithuania’s senior architects. Personal archive of John V. Maciuika

I was just starting at Berkeley, where there was one formal course not on the Baltics per se but more on the Soviet stuff. I asked if I could write a research paper about Lithuania as a newly independent nation and, after a semester of research, traveled to Lithuania. My uncle (the one who had been sent to Siberia) had been an art student in the Vilnius Fine Arts Academy and was friendly with many of the prominent architects whose entire careers went by under Soviet rule, and as a sculptor he had collaborated with many of them on public projects and monuments. All he had to do was pick up the phone and we had appointments the next day. Interviewed in the book are four architects: Algimantas Nasvytis, Vytautas Edmundas Cekanauskas, Vytautas Bredikis, and Gediminas Baravykas.

Photograph of the Lithuanian architect Gediminas Baravykas (1940-1995). Personal archive of John V. Maciuika

Vytautas Brėdikis and team, new architecture building of the Vilnius Academy of Fine Arts, Completed 1981 and photographed in 1992 by John V. Maciuika

A major theme in these interviews seems to be to what extent were these Lithuanian architects tied tightly to the Russian-designed top-down planning? How were they able to distinguish themselves in an unforgiving, fairly rigid system?

That’s a great question. Here I think we need to look at the Soviet Union from the standpoint of it having being the largest country in the world, covering I-don’t-know-how-many (I think seven) times zones. I mean, it’s a vast territory. Soviet central planning took place in Moscow, and the Baltic republics were, in effect, on the periphery of the Union – at the extreme western end of Soviet territory. That set up a dynamic in which you were educated under the Soviet system. If you were lucky, you also got to visit and study in Moscow for a time and develop a network. But when you’d go back to the Lithuanian SSR, what you had was a Lithuanian-speaking population.

Everyone had to study in Russian at university. And the Communist officials were local Lithuanians who had varying degrees of loyalty to the center and to the Communist Party. What the architects were able to do was to triangulate the best they could. They were the first to admit this in the interviews. They said – look, we didn’t have a lot of degrees of freedom. We were just trying to serve as a kind of buffer between this unforgiving Soviet five-year planning system in which architects were reduced to draftsmen. Everything was done according to the square meterage of living space allocated per person, per year. The architectural profession shrank down to a minimal role. And so they would try to intervene whenever possible. That was what I was there to try to report on: how did Lithuanian architects get things done when they were just tools of the Soviets? And to what extent were they resistors trying to do something on behalf of their occupied home country?

Can you give me some examples of their strategies in getting things done?

When they were young professionals, it was during the Khrushchev thaw (1955-1957). Khrushchev tried to loosen things up and promoted self-criticism in the Soviet sphere. At the annual Congress of Architects in Lithuania, a young Lithuanian architect who was a graduate of the Vilnius Academy of Fine Arts gave a speech criticizing what had happened in the country from 1945 to 1955. He said that they were destroying old historic buildings – if we allow things to continue like this, future generations will look back at us and call us barbarians for destroying our own heritage.

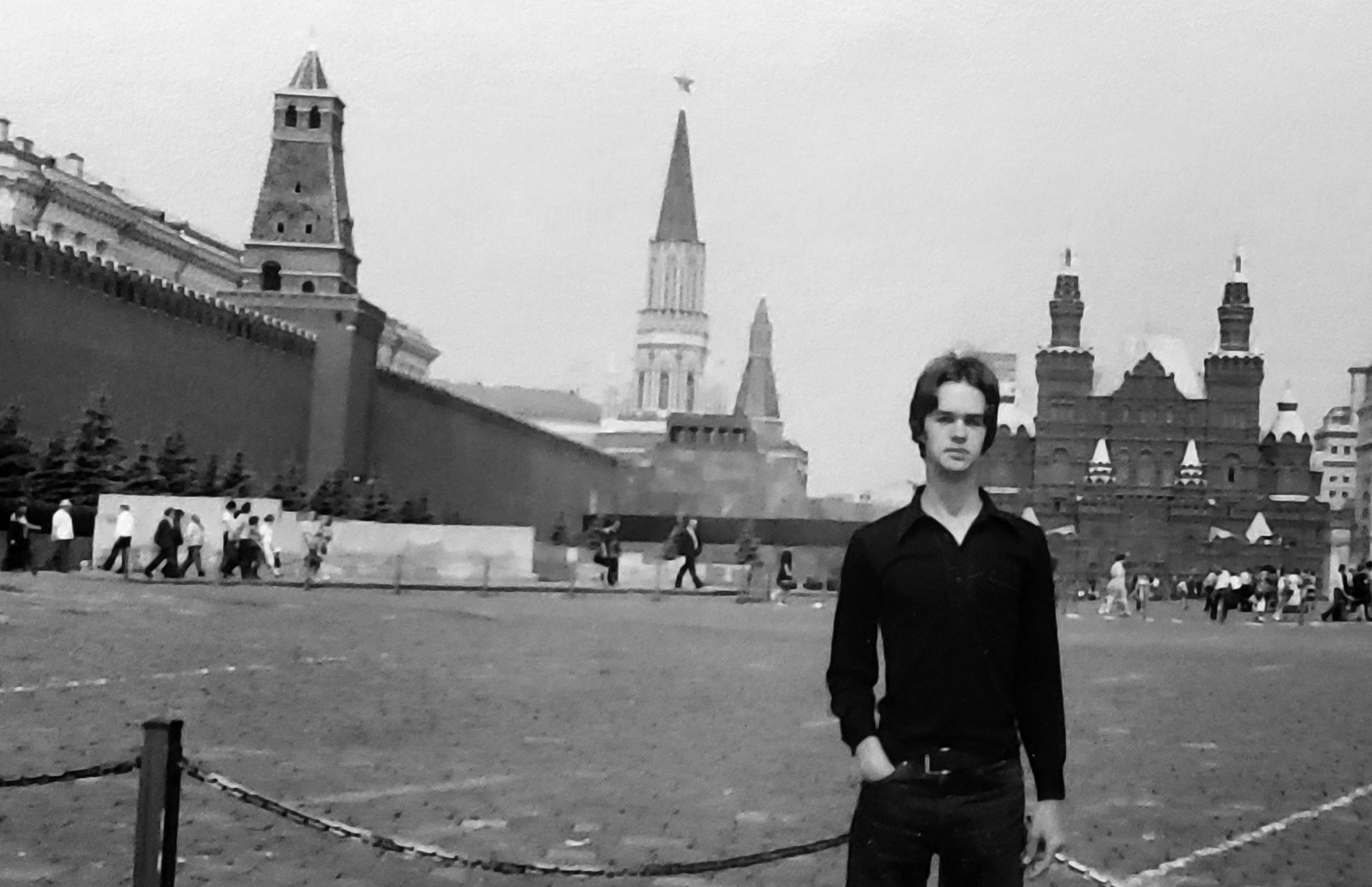

John V. Maciuika in Moscow’s Red Square in 1980, aged 14, en route to Lithuania. Visible in the background from left to right are the fifteenth-century walls of the Kremlin, Alexei Schusev’s Tomb of Vladimir Lenin (1924), and Vladimir Osipovich Shervud’s (Sherwood’s) State Historical Museum (1881). Personal archive of John V. Maciuika

On a practical level, what that translated into was that local Lithuanian Communist Party officials gradually replaced the Russian architects with Lithuanian architects, who then began to preserve the old town of Vilnius as well as they could. One big victory occurred around 1958-1960, when Khrushchev ordered the construction of mass housing. In Vilnius they made a rule that they were not allowed to build satellite block towns inside the perimeter of the old city of Vilnius. They moved them across the river, to a hilly forested area. What that did, in effect, was create a green belt that protected and preserved the old town yet allowed modern construction of these concrete block apartment buildings to proceed in a different location that was still connected to the city but not in the city.

My father used to tell me an anecdote that described how things worked. When they got money from central planning in Moscow to do a certain amount of work on city infrastructure in Vilnius, the local Lithuanian officials would divert that money for the construction of the Baltics’ very first super-highway between Vilnius and Kaunas, the latter having been the interwar capital of Lithuania. It was a very proud moment when they unveiled a six-lane highway with these fancy exit and entrance ramps.

It developed into a kind of dance in which they would first try to improve matters in whatever small ways they could. Then they would work on the local Lithuanian Communist officials who were in charge, convincing them that this was going to improve the quality of life in one way or another in Lithuania itself. But the Lithuanian Communist officials wouldn’t grant the necessary approvals because they were afraid of catching hell from Moscow. And so they would work on these guys until the local officials would say, well, okay, if you can get Moscow’s approval, then we will support the project. Then they would travel to Moscow and try to get an appointment with the minister of construction for the entire Soviet Union. But the guy wouldn’t give them an appointment. And that’s when they would leave “the briefcase”. Right there outside the guy’s office. They’d go back to their hotel and the guy’s secretary would call and say that somebody left their briefcase here. And they’d say, no, we didn’t. And they’d wait a week – you know, until after the champagne had been drunk and the sausages and cheese [in “the briefcase”] had been eaten. Then they would call again and say, we’re trying to get an appointment with the minister of construction – and they would get an appointment. That’s funny. And then the whole process would begin again. This type of arrangement could take years and suffer various revisions, setbacks and budgetary issues.

What elements of Lithuanian heritage did they wish to preserve?

Some areas of the city that had been damaged in World War II. Early on, the Russian approach was to just tear down the entire street and build Stalinist-style apartment buildings. What the Lithuanians tried to do was a little bit more contextual – to preserve what they could. So even in the seventies, when I went there, if a building had to be reconstructed in some way, they would try to preserve elements of the original structure and do what architects call “a reveal of details” of the historical building. The new building would be sensitively built and integrated with the older one. There’s a modern movie theater, from the seventies or early eighties, that was built in the form of a house with a traditional historical roof style and roof lines. So even though it was recognizably a modern construction, its materials and overall composition fit into the historical context.

It was necessary for the architects working under the Soviet regime to be able to speak a language that conformed with Soviet ideology about the new “communist man” or the new “communist individual”. And there was a lot of propaganda and writing and policies and projects that were supposed to promote this. As an architect, you had to be able to speak that language, but then amongst themselves, they’d say, where can we get access to architecture journals from France or from Scandinavia – from Western countries? Where can we see what the rest of the world is doing in modern architecture? Even though they were not politically independent, they wanted to be able to show Western elements of modernism in some of their projects. They wanted to be able to say: even though we’re not politically free to be part of your community, culturally, we still feel part of your community.

John V. Maciuika in front of the Lithuanian Parliament building (designed by the architects Algimantas and Vytautas Nasvytis) and the remains of protest barricades in Lithuania’s campaign for independence from the Soviet Union, June 1992. Personal archive of John V. Maciuika

Lithuania led the way toward seceding from the Soviet Union through desiring cultural independence to the extent that it was possible during the Soviet era. And then the minute the cracks started to appear in the eighties, with Gorbachev, they started to agitate more for political independence. They admired the work of Alvar Aalto and wanted to design buildings that had clear compositional references to buildings in the West.

Vytautas Brėdikis, Site Plan of Lazdynai Satellite Town and Housing District emphasizing separation of vehicular and pedestrian streets, 1964. Personal archive of John V. Maciuika

Can you talk about the Lazdynai Project?

I think that may be the most successful example of what we call Lithuanian modernism. On the one hand, it’s a giant satellite suburb of Vilnius where 30,000 people live, perhaps 40,000 by now. It was begun in 1962 when the Soviets had actually sent delegations of Soviet architects to Finland to look at modern architecture – because Finland at the time was judged by the Soviets to be a non-bourgeois Western capitalist democracy that was acceptable for them to visit and study. And when they came back to Lithuania, these young architects received a commission to work on Lazdynai as a housing project. They said that the landscape in Lithuania was very similar to the landscape in Finland. Aalto believed that the Bauhaus satisfied formal expressions of steel and glass and concrete, but that it did not go far enough to take into account the psychology and emotional life of the individuals who occupied the buildings. So, Aalto humanized his projects, aligning them much more closely with nature.

Aerial view of Lazdynai Satellite Town and Housing District outside Vilnius, designed and constructed between 1962 and 1974 by the Vilnius Urban Planning Institute (collaborative team led by Vytautas Brėdikis and Vytautas Čekanauskas). Personal archive of John V. Maciuika.

Aalto built these prefabricated buildings right into the forest, straight up the hillside like a set of stairs. Every apartment that was on top of another apartment used the roof of the lower apartment as an outdoor terrace that was in the trees. And he even used some natural materials to underscore that point. He situated the buildings to take advantage of the views, to be set within nature. Those elements deeply impressed the Lithuanians, although they didn’t have the freedom and budget that Aalto had. But they did succeed in working some of these principles into their designs. They worked with Smuelis Liubeckis, a local manager of a concrete factory who shared their anti-authoritarian point of view. The idea was to turn out prefabricated concrete parts that would allow them to break the plan of these apartment buildings in such a way that they could follow the line of the topography of the hillside.

View of Lazdynai Housing District, 1974. Personal archive of John V. Maciuika

Aerial View of Lazdynai Housing District, 1974. Personal archive of John V. Maciuika

If you leave the old town of Vilnius and take a bus through Vingio Park (a green space that has a stadium in which they used to hold song festivals and stuff like that), you cross the river by a bridge, go up a hill, and Lazdynai is right at the top of the forested hillside. The site does actually resemble the types of places that Aalto was building in Finland, but it is outside the city proper. The project took a little longer than was expected. It was built between 1962 and 1974, with all the kinds of resistance you might expect from Soviet officials from the Lithuanian Communist Party. Even though the Soviet officials had resisted it for so long, once it was actually completed, they turned around and awarded it the Lenin Prize for Architecture in 1974 – as the best example of communist architecture. It was a weirdly bifurcated identity in which the Lithuanian architects were trying to do good modernism and refer to the West, but when they talked to the Soviet officials, they would say, well, it’s really Marxist-Leninist ideology that we’re practicing.

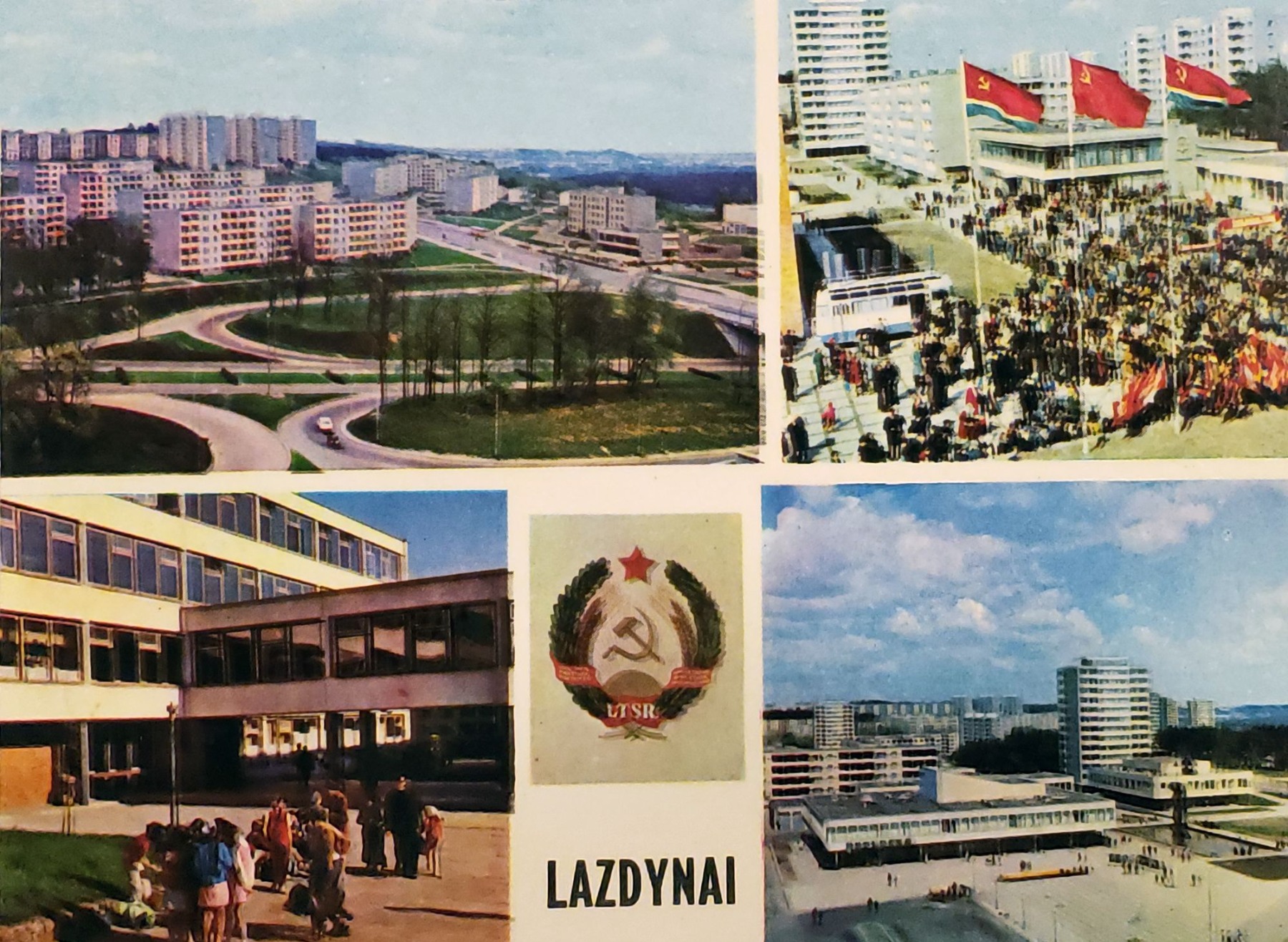

Postcard featuring the Lazdynai Housing District in Vilnius, 1974

The other big achievement at Lazdynai was that it was the first and one of the few projects of its type where they managed to complete the urban planning and layout of the entire satellite town. There were major vehicular ring roads, and through the middle of the project – where the housing apartments were – they would have pedestrian-only streets. That meant increased safety for all the residents, especially for the children who could play outside and be on these streets with no vehicles – your ball is not going to roll into the street and get hit by a truck. That’s huge. Along these pedestrian streets they concentrated services: the kindergarten, the laundromat, shops and grocery stores. They were trying to build a community instead of just having a random scattering of grim concrete apartment blocks.

The only instance of “stepped” housing apartment blocks in the Soviet Union, at the Lazdynai Housing district, showing the influence of the Finnish architect Alvar Aalto in Lithuania in the 1960s and 1970s. Personal archive of John V. Maciuika

That was a real innovation for that moment, was it not?

It was directly taken from a project being done in Southern France in the sixties called Toulouse La Miraille, which was a satellite town built by a bunch of rebel architects who called themselves Team X. They were trying to use more natural metaphors in modernism, and they separated the vehicular streets from the pedestrian streets. They even built some of them elevated, up at the building level. The “streets in the sky” were really concrete walkways that would go above the traffic and connect directly to the buildings, thereby not exposing people to the dangers of fast-moving traffic.

What happened after Lithuania became independent?

I’d say there was a bit of a fork in the road after independence. Initially, it was perceived by the architecture community as a bit of a tragedy. It became possible in independent Lithuania to own private property and to build houses through private contractors, which was not possible under communism. Immediately you had all these McMansions everywhere, springing out of the ground like mushrooms. Oversized monstrosities that represented the nouveau riche. That’s where architects try to step in as educators of taste and say, look, it’s not all about how much square footage you have and it’s not all about having a triple-height entrance hall with a staircase. It’s also about making your building fit the site and how it interacts with the movement of the sun over the site, how air and light come into the building...as well as to facilitate healthy living and have the buildings fit together into a community of buildings.

Beyond the McMansion tendency, there was one in architectural education. They introduced a great many changes that conformed to Western modern architecture curricula. Now they’ve got parallel tracks running at Vilnius Technical University. You can study architecture in the Lithuanian language and get an M.A. degree or you can get an M.Arch. in the English language. There were students from the Middle East, from Arab countries, who came to study architecture because they could do it in English. And they were looking to the West to do a master’s in architecture in the style of Western curricula.

What are your thoughts on the current EU initiative on the new Bauhaus?

I lived in Germany for three and a half years doing my dissertation and my first book, Before the Bauhaus. I visited Weimar and Berlin and saw what happened after the wall came down. In each region, they had capitalized on their heritage. In Weimar, for example, they renamed their university the Bauhaus University.

The EU New Bauhaus Initiative is interesting because it appears to take the name of the legendary art school founded by Walter Gropius during the Weimar Republic, but updated for a twenty-first century ethos of international cooperation, environmental sustainability, and innovative design. The original State Bauhaus in Weimar (1919-1933) was not known to be particularly eco-conscious, although it did recycle found objects to create original abstract art in the post-World War I age of German poverty and scarcity. The school was, however, very international, quite progressive, and always extremely open to new ideas such as better living through design. This, in turn, owed much to the earlier ideas of William Morris, the British applied artist and "prophet" of the Arts and Crafts movement. Thus, under the banner of a "New Bauhaus", we see a historic name repurposed to once again promote internationalism, progressivism, and openness to new ideas. These were precisely the qualities that animated the Bauhaus school at its successive homes in Weimar, Dessau, and Berlin, and were also the exact characteristics that led cultural conservatives, provincial nationalists, and eventually the Nazis to persecute the Bauhaus until it shut down in 1933.

Cover of the bilingual Lithuanian and English publication, Lithuanian Architects Assess the Soviet Era: The 1992 Oral History Tapes, edited by John V. Maciuika and Marija Dremaite, published in Vilnius in October 2020 by the LAPAS Press in collaboration with the University of Vilnius

What question or questions have I missed?

I would offer only a reflective touch upon the introduction to my book where I discuss the whole subject of cultural identity concerning anyone who came to America like my parents did, or in my case, a child who was born in America but raised with the Lithuanian language and culture, attending Lithuanian schools on Saturdays until eighth grade, and going to Lithuanian summer camps and stuff. I was experiencing two different cultures from the get-go, right at home, growing up with both a Lithuanian/Eastern European side and an American side. And I think it sensitized me from the earliest age as to how one goes about trying to fit in and the ways in which one clearly feels like one does not fit in.

When I went to Lithuania to talk to those architects in my twenties, I was well prepared to do so because when they started to tell me their stories of a bifurcated identity, I understood what they were saying. They were Lithuanians, but they were also part of the Soviet Union. If they wanted to work as architects, they had to conform to what the Russians commanded, and they had to figure out how to fit in and how to change things to make them more Lithuanian. And that made all the sense in the world. To me, it was a real impetus for the project.

But now that both my parents have passed away, in 2018 and 2019, I’ve been a little more open (even in the Lithuanian press) in interviews regarding talking about what Lithuanians did during World War II, and I have begun to ask new questions. What about the Lithuanians who were already Communists in the 1930s? What about those Lithuanians who didn’t feel like it was necessary to look to the West and go to America? What about the Lithuanians who took refuge in Moscow? What about the Lithuanians who moved east because they thought that the whole communist thing looked pretty appealing? Maybe they didn’t like capitalism, or they didn’t think that realism was providing the right answer for people. We weren’t really shown those figures in Lithuania. We were raised as good patriots, and anyone who went to Moscow during World War II was not seen as a Lithuanian patriot.

There was the whole rhetoric of the Cold War. I remember standing in our kitchen at age four or five, where we had a world map from National Geographic up on the wall. My parents would listen to the news at dinner every night on the radio, and I’d hear about the Vietnam War and the bombing of Cambodia, etc. I was only five years old, but I would look at that map and try to find these locations. And then I’d look at the map and say, where’s Lithuania? And I’d look at the spot where Lithuania was. And all you could see was this giant red Soviet Union.

***

*Roslyn Bernstein is Professor Emerita of Journalism at Baruch College, City University of New York. She is the author of Boardwalk Stories, Illegal Living: 80 Wooster Street and the Evolution of SoHo and Engaging Art: Essays and Interviews from Around the Globe. Her cultural reporting has appeared in Guernica, Tablet, Huffington Post, and many other venues. Roslynbernstein.com

Title image - John V. Maciuika in April 2021 in Connecticut. Photo: Paula Matthusen