Towards an Architecture of Caring Ecologies

An interview with a Swedish architect Erika Henriksson

Erika Henriksson is a Swedish architect currently based in-between Norway and Sweden. In her architectural practice, the foundational base is a relational approach in which people, materials, and places involved in a project overcome pre-conditioned hierarchies of neoliberal production by considering feminist perspectives through a building process that becomes an experience in itself.

At the moment she is working on her PhD thesis, “Performing Architherapy”, which focuses on a relationship-based building model as a form for facilitating caring relations. In the time between January 2015 and August 2018, Henriksson worked on an exploratory building project in a rehabilitation clinic in Järvsö, Sweden. Having formed contact with two people living in the rehabilitation clinic who had found an abandoned mortuary, together they started to develop the project of restoring the building while creating relationships with other people living near the clinic. The project, processual in its nature, was an exploration in a building practice that connects and encourages a network of caring ecologies.

Maybe you could start by elaborating on how your work at the rehabilitation clinic began and how it was linked with your research.

It started with me having gotten a practice-based PhD position with the overarching theme of architecture and health. I was, in a way, looking for a case that I could work with, and then I accidentally met a friend of mine who had been at this clinic and had met some people living there who had, in turn, found a building and had an interest in working with the building. It sounded very interesting, so I wrote them asking if they would be interested in meeting with me for a possible collaboration. From then on, the project started – the whole process of building was my research, and the project defined its framework. The residents and I also had very good chemistry, and we decided that we should form a project together. And the framework was this building, the idea of building as therapy.

From there, the process has been the transforming of the building. That has been the main method of working. And research-wise, from my perspective of being an artistic- and practice-based researcher, it has had two exploratory paths. One was performing this idea of therapy; it started with an idea – build as “therapy” – which was explored through a process of working. The other path was constantly reflecting on the methods of working. Practice-based research is very intertwined with method, outcome, and theme, so I was constantly trying out different situations for being able to do research in a real-world environment, together with people. I think one of the crucial parts is that the knowledge production was not "me" doing research on somebody else, but rather figuring out how we – with our different experiences, backgrounds, and knowledge – can work together. Then it transformed into understanding how will we do that: where can we find common ground, where can we discuss with each other, where can we exchange knowledge, which words should we use, and which types of settings should we be in to be able to work together.

Under this framework, how was the architectural building process tied together with the community-building process?

This project has been very open and dynamic, and this makes it sometimes hard to label it under one specific terminology. When it comes to community building, I would say that it’s not been a project about community building because in this clinic, and in terms of people coming together, some were there under specific conditions. Some people were very locked in. Some were very insecure. Not all of them were in a state of wanting to interact with a lot of people. Mostly it has been about changing situations depending on what was needed at the moment and who was a part of it. For a lot of people, it has almost been a kind of requirement. For example, they would say: I would love to be a part of this, but maybe just you and me at first, apart from other people. For many people, it was something that they hadn’t done before, and this feeling of being in the midst of many people at the same time felt stressful for some.

But I would say that for some, the process and the project has been a meeting point, a meeting point between different people; at some moments there were a lot of people working, but this shifted over time. I would like to say it was a social project, and that also meant that it was a relational project, acknowledging that people are different, that they have different needs. But it’s also been about working together with the residents of the clinic. And also, a part of the project builds upon me building up relationships with different people and environments. It’s not only about residents but also involves staff at the clinic and local people with local skills and knowledge. And all those different people have been involved, and sometimes at the same time, but it’s also been more of a network formation.

How did you position yourself in this project, taking into account that you came in as someone with architectural knowledge?

I would say it’s sometimes hard to speak about these projects because they contain so many different aspects and layers and small explorations within them, one of which was about me exploring my role and what my role should be. It wasn’t clear for me from the beginning. In what role am I here? I came here formally as an architect, as somebody who has knowledge, and as a practice-based researcher. But what that meant in that context, in that project, was really hard to figure out because in a social situation, you must understand what kind of power you have and how you use that power. How can you use it differently? But I think it was important to start with me getting in contact with the people living at the clinic and us forming a project.

My relationship with the clinic and the staff grew with time. For me, it’s been important that it wasn’t a top-down approach but rather that the relationship grew through the residents. After some time, it grew into a situation where they also allowed me to use the workshop, they gave me a storage space, and they let me eat lunch and dinner there – so every day when I was there working, I was a natural part of the environment. But within a group, there was a power imbalance that I constantly had to work with – figuring out how we can work together as a group. The project was about the building process, and I came in as an architect, an “expert” in this, and I pushed the process into fast forward. So, it’s been about me unlearning and not trying to push my methods and ideas, but instead seeing how I can learn about other ways of doing this.

I also came in as someone who has the ability to move and has freedom in my life, and also, later on, I am someone who narrates the story of this work. So, I’ve had a big power position. I have constantly tried to understand how I can let go of that, and how I can create situations wherein other people can take control of the process.

Could you elaborate on the process of exiting the field? Are you still in contact with people living there?

I still have contact with my collaborators, and we still call each other and talk. Also, when I present the project and show pictures of it, I ask for their permission. They have a say in whether they want to be shown or talked about. But I feel that this is a struggle. It’s a condition that I came to terms with, one that you have to be conscious about, but there is an extractive part of it. This is something that is very important to discuss in these kinds of social projects because you can also take a very extractive and voyeuristic role. As a researcher and architect, I come into a place where people are in a more confined position, and there is giving and sharing for some time, but then I can move on but they can’t do that in the same way. So there’s the issue of how to deal with that.

I think you should be very aware of this. You cannot expect that such a project will change other people’s lives or that it will be a solution. But we can be very careful with what we say. To really be respectful with how you continue with things afterwards. And, while there, be very conscious of and reflect upon what you’re giving back. I think it’s about creating something that also “gives back” while being there – it’s not just showing up there and talking, seeing the people as my participants in this; what you do during this time is really not just for you – it’s for the benefit of the project and the process.

Maybe we could turn the conversation towards the material layer of the project. As I understand, you used locally sourced materials. What was the relationship between people, materials, and the place?

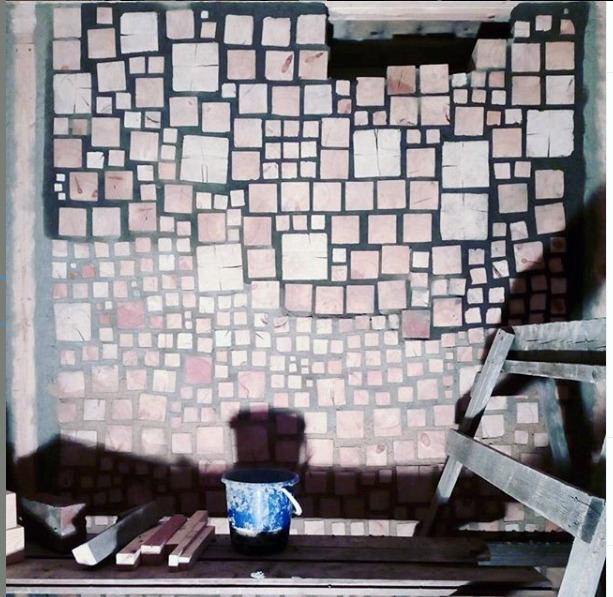

It comes from many different directions, but the general idea behind “building as therapy” has been about creating caring relationships between all the different entities – people, materials, environments – that take part in the building process. Here the approach was to gather all the materials we build with locally. There were many different reasons for this, one of which was to follow this idea of building up relationships with the surroundings as a social approach for being engaged with your environment and building up a deeper, more empathic relationship to the material world. So, the specific situation was also used as a process. It’s also been a way of thinking about social situations, marginalisation, and exclusions. It was about developing an approach of engaging with the world very bodily and being curious and creating a building process as a way of experiencing and learning about your surroundings.

It was also about building a deeper relationship to the materials and the material world, which is a big part of architecture and creating architecture, but it can sometimes be a white surface between two lines in a drawing. It was about following the materials back to the environments where they were formed, and through this, also starting to create deeper empathic relationships with them. In gathering something, seeing it in different stages, you start to understand the whole process of it. For example, by gathering clay, you start to talk with people and ask them where to find it, and then you find out its geologic age and so on – suddenly you start to learn about history. You start to understand that this material was formed a million years ago, and it gives you a better understanding of time and formation, and maybe also a little bit of respect towards what you have in your hands. This was the idea.

But another aspect was building up relationships to local knowledge. Some of these materials were gathered with the help of farmers and people who knew where to find them. At the same time, it is a way of building up the autonomy of the project. By building in this way, you can keep the budget much lower, which means that you can be autonomous in what you do and invest time instead.

So it’s more of an intersectional approach. Could we also talk about playfulness in the building process? How important is it to bring play into the rigid system usually associated with construction as such?

Building is a passion for me. But it also involves being playful in it. For me, being playful means being open and dropping any preconceived ideas about what things should be and what they are – to allow everything to be multidimensional. In a way, it is about having an approach that is similar to what we see when kids are playing. A table can be a table, but it can also be a landscape or a horse. And I think this mindset is very important. It has been a participatory process, and most of the time it’s very crucial because it’s a way of not taking yourself too seriously as an architect.

You know, the conventional approach of working is having control over everything and deciding on an outcome from the beginning, whereas working in a participatory process, not knowing the final outcome makes it interesting. It is the sum of everybody working together – where everybody can learn something. It’s about improvising and accepting that. And then there is another aspect regarding power positions. It can be a way of loosening them up. You can start playing with roles and hierarchies, and it’s a way of building up trust. We’re moving together. To be able to let go of your control without thinking that you are better than somebody else. It’s about the meeting. In this project, this was a way of creating different methods. From the beginning, it was about spending a lot of time together, moving around, and allowing almost whatever came into the process to be a part of it. It can lead towards drawing out ideas of the building process on the floor and doing charades instead of building models, or moving around in the landscape and looking at the staircase, but suddenly the staircase brings other connections to mind – it was a way of building up a common ground from what we were doing. And that didn’t take place while sitting at the design table – it was more about making it into an adventure.

Can we also explore the participation aspect a bit more? How did you approach this project acknowledging that not everyone has the same capacity to participate?

I decided very early on that I don’t have expectations for anybody to join or to be part of it. It had two different phases, and there were different ways of working with people. There was the first phase – when I met the two residents of the clinic and we formed the whole project together. They had the initial idea. And that was a very intense way of working together, but then it wasn’t a question of time. We all wanted to give it some time and explore it. Then later on, when we wanted to build, it became another thing. They also left the clinic after some time, and the project faced the challenge of finding a new way of working. This was a new situation.

The way I solved it was to set up a process that was very open to people engaging, joining, and leaving – without having to commit if they didn’t want to. Maybe I had an idea of what a participatory project could be when I began this project, but it was very good that I had a framework that I could adjust to the changing situations. I came up with an approach that would allow people to join in and leave whenever they wanted. This joining and leaving was, in a way, a quality in itself. It is also about what it is that you want to achieve – the idea here was very much about the experience of building and what happens while building, or how you build up relationships. It was almost a bit easier to explore this when there weren’t that many people and when there were people who wanted to join just to be involved in the process – and then we would share experiences about what that meant. As I said, it was almost a quality that people came and left. But from my perspective, as someone who’s running participatory processes, you need to have time to be able to create a process where people can influence it back because then you need to build up this trust.

Where do you draw your inspiration from? The Matrix Feminist Design Cooperative also tried to incorporate similar non-hierarchical practices, but I understand you also base your work on materialist feminist theoretical grounding.

It’s interesting to talk about inspiration because it is a lot of things coming together that influence you. It’s like putting together pieces where it’s sometimes even hard to describe in what way somebody has influenced you. Because it’s usually, you know, you see something, you hear something, and then it forms in you and it becomes something that you want to do. But I have definitely looked at Matrix and different materialist feminist practices and spatial practices. I have followed Matrix almost since I started studying architecture and when I entered a process of searching and trying to develop my own methodology for working with architecture. I think the most influential aspect of the practice has been showing and encouraging people that there are other ways to engage with architecture other than conventional manners and procedures.

I think this is almost the most important thing about inspiration. You see other people that go their own way, and almost that alone can be very inspirational – to see that there are possibilities. But also, what Matrix showed is that it matters how you practice, how you organise your work, how you structure it. When going to school and learning the conventional approach, this is something that is just taken for granted. And then suddenly somebody says that it comes from a certain perspective – it is a format that includes certain people and values that can be executed. But if we organise our work in a different way, then suddenly, different values can be brought up in equivalent. For example, this project has built on not having a hierarchical approach to architecture. And to value the relationships by asking what can be built by this process other than economic interests. And that has challenged the structure of the whole world. In my opinion, they were quite radical when they were doing this, and they were very inspirational.

When Matrix set up this practice, women were even less involved in shaping the built environment. It was both about them being able to work, but also what kind of questions they could address. It was quite radical when they wanted to even out these hierarchies within an office, i.e. not having a director and employees. And about thinking of other relationships with the clients. They wanted to allow clients to be more involved in the design process, and through that they developed a strategy of working in a similar way of teaching how to read drawings or making models that would be good for having a conversation, or even going to sites, looking at buildings together with clients and then discussing them. They were really designing an inclusive process.

Do you have any ongoing projects at the moment in which you’re using the methodology you have created?

At the moment, I am primarily editing my PhD and planning a small-scale building project together with two colleagues, Anna Sundman and Emily Aquilina, through the idea-driven organisation AES (Architectural Environmental Strategies). This project will happen later this spring at the exhibition space Färgfabriken, a node for contemporary art and architecture in Stockholm, and it actually has a lot in common with the methodology of Architherapy. This means that it rests on the ideas of openness, collaborative and participatory processes, and sustainable building. In combination with this project, we are also planning an exhibition and seminar that will be a presentation of eleven building projects that have been done through AES cooperation with BIØN, which is a practice-based research network for sustainable building.

For me, my methodology of working and this approach of wanting to work openly and relationally includes both people and materials. The way of working together with people as I did in the rehabilitation clinic project is extremely time-consuming. You cannot always go to a situation and expect that you will have the chemistry to make it possible to work together. So, I kind of evaluate the different projects based on what I think is possible and what kind of time I have; this relational approach is usually used in terms of working with materials, working locally, and being social in the sense of building closer relationships to an environment. But maybe the construction part doesn’t involve people in that sense. I’m constantly training myself to work relationally, both with materials and social relationships. I haven’t determined that I should always work together with people because then you could easily end up in a situation where you’re trying to force a process into happening.

Do you think your Architherapy approach is applicable to larger-scale building projects? Or is it more suitable as a small-scale methodology?

I think it is more of a small-scale one for me because that is the way I can engage in it. It builds on an ethos of being very attentive to your surroundings and acknowledging resources and seeing how you can use them and how you can allow openness in the process, which is a way to work relationally. Maybe you could do it on a bigger scale, but I think there is a limit to it. It’s very hands-on and it’s a methodology of working with architecture, and it has its own techniques and methods. But at the same time, I also see it as a concept or an explanation of a strategy, or an approach where it’s just about how you engage with what you’re doing, and you can apply that on a lot of different scales in the way you include people and work with materials.

Under what conditions can building grow into a form of healing?

The idea of healing ties together with the idea of therapy. And that was built upon a reaction against a worldview that forms separation, as in creating distances between people, between people and their environments, and between people and materials. The idea of healing has been about creating relationships instead. It has been about localising how you can craft a building process to build upon social and material relationships, which is then seen as the healing process. One part of it has been about shifting this anthropocentric perspective through the way you are building. Through working closely, you start to build up another relationship through them. But then it’s also a part of a social and individual level. It’s about crafting and building situations where more people can be included and be a part of shaping the built environment.

I think it connects to this question of craft and architecture, which I see as a very relational approach. When you are working with a material, you also train yourself in working relationally because you work very actively with the material. You cannot have this idea of somebody who controls – you need to know how it functions to adjust yourself to it. And I think that working in this way with craft is a way of learning to learn yourself. You know, the people who were getting involved in the project started to learn a technique, materiality. Suddenly they started to trust themselves in making an evaluation, for example, “this is too little sand, we need more clay”. And while doing this, you also acknowledge yourself as somebody who has knowledge, and you discover that you have competencies and capabilities – this is how it can be part of the learning process and a process to grow in.

It’s also about discovering capabilities; exploring being in a moment where you can create an experience with being connected with the world. I mean, it’s a little “fluffy” to talk about, but I think everybody who has worked with creative things, crafts and materials can describe this feeling of becoming a part of what you’re doing. That kind of tactile engagement with materials and the rhythmic process of building can in itself have a very stress-releasing or calming effect. You can approach architecture by seeing it as something grand and building a few relationships, but it can also just be about thinking how you craft a building technique, or the way you’re building, which can also be an experience in itself.