Of Borders And Bees

Paula Veidenbauma

An interview with urbanists Johanna Richter and Marcell Hajdu

Johanna Richter and Marcell Hajdu are urbanists currently based in Germany. In 2021 they worked at Narva art residency (NART), where they explored bees as a medium for reconnecting with nature in the framework of their project ‘Buzzing in Narva’. While staying in Narva, the duo also explored the concept of borders, both visible and invisible, in this area of land located in-between Estonia and Russia. Having studied urbanism at Bauhaus-University in Weimar, they incorporate theories of contemporary critical urbanism in their artistic practice of small-scale interventions.

Maybe first you could tell me more about your project ‘Buzzing in Narva’. What was behind the idea and how did it come about?

Johanna: We applied for the Narva Artist Residency in 2018 because a few years ago I had studied Urban Studies at the Estonian Academy of Arts as part of an Erasmus exchange, so I knew Narva and I was always following what was going on in Tallinn. I saw that NART was coming up. In the end, we applied with the theme of using bees as a metaphor for nature overcoming the structure of the border as a concept. That’s also how the idea to look for beekeepers and to research them along the border between Estonia and Russia came about.

Marcell: I could just add that it was also three years later that we actually got to go there, and we were, at the time, straight out of our master’s at the university. I think it was one of the first attempts at experimenting with what interesting things we can do with our knowledge and what you can do with this kind of education outside the regular path one would go down. I actually think that it happened quite organically because after that we got our jobs, and then the pandemic happened, two years flew by, and then we got this chance to go and revisit the idea, but also to frame it a bit differently. Just a great opportunity to come out of the routine and see another way of engaging with the city and other things that were intriguing for us.

You call yourselves urbanists, right? How do you position yourselves in the field of Urban Studies?

Johanna: I think Marcell and I still have totally different points of where we are at the moment. We are in different contexts. But as urbanists and in relation to art, and also what we did there in Narva, we approached it very openly. We went there and developed an idea more like an open process in relation to what we found there, so maybe that’s something Marcell meant by calling it ‘an organically developed’ project. Being on-site. And possibly that’s also another point, namely, that in the field of urbanism or urban planning, it happens very easily that you enter a top-down approach and you’re looking at the city before even entering it.

Before we arrived, Marcell started drafting maps, and it was a very different experience on-site. In the end, another map came out as a result. Possibly that’s also a reflection on urban planning and art, more like a potential to look at our environment in a much more open way, and also looking for beauty in a city. The small things.

Marcell: It is also true that calling ourselves urbanists is the simplest way of saying a lot and nothing at the same time because it’s so broad. We are, of course, connected through our interest in cities and how people live in them. In a way, it is still a good description of what we are doing, but at the same time, it doesn’t say much. And on my part, I am now working more in an academic environment, but I also come from a more practical background.

My first education was in engineering. And art, as Johanna said, in this instance with this project, was a way of going off of the beaten path. A way of leaving behind this kind of ‘top-down’ mindset you’re in when you study to become a planner. And to me, it’s also a way of communication, another way of communication. Not a descriptive one, but rather one of engaging with other people and finding a common language.

You chose urban intervention as your exploration method. Do you see any limitations to this approach regarding participatory involvement?

Marcell: I think this word ‘intervention’ was something that we were thinking about from the very beginning. Because there was this idea of creating something. By the time we were there, it got a bit less product-oriented, and we were more aware of seeing if there is a space for exploration and thinking. Especially in such an environment where you have never been, you have no real understanding of the space, of the relations, or of people. The only way you can come a little closer is through the people who live there and are there. For us, at least, it always goes without question that we try to get into contact with as many people as possible, which is never easy because of the language barrier and things like that, but in the end it is also a mapping process for us, or it is for me, at least. To map these human relations and to try engaging with people. It was a process of working towards it, and only by the end of the project did we manage to create a little workshop where more people were brought in.

Johanna: Participatory… In a way. That’s also how we try to approach things. It’s always about seeing the people, the neighbourhood, who is living there. They are the experts. They know their city. In regard to beekeeping, they are the experts of it all. By the end, we wanted to find out this knowledge, collect it. However, I am not sure if it was a participatory project. We aimed for that. In the end, we also did this workshop. But for me, in order for it to be called participatory, it needs much more time and interaction. In the one month that we were there, we finally achieved closer contact. Maybe that was the starting point of it all. But in order to really develop a project, to say that it was participatory, it would need more time, in my opinion.

Maybe we could talk a bit more about planetary urbanism, which urges us to change our conception towards not looking at cities as isolated islands, but by taking a more intersectional approach. In your work, you have also been looking for these invisible borders. I find it interesting that, while based in Narva, a city with a very distinct physical border, you were also looking for invisible boundaries where the rural and the urban meet. Were you interested in this dichotomy?

Marcell: Our fascination with Narva and this project started with the idea of a political border, a state border, which is something we have explored a bit earlier in our work. But, at the same time, the topic of nature came up at one point. The idea was developed for such a long time that I don’t necessarily recall how we got into it. But maybe I can say how I feel about it now, half a year after the end of the project. It shifted from the idea of a border as separating one political entity from another towards a more abstract border. At least in my head, it meant dealing with the city, at the same time trying to deal with nature as a topic. And in that sense, the real border did in fact become this difference between a totally urbanised planet – if you want to say so – and an outside that is inaccessible to us. In the end, we did see this chain of locals, and we explored how local people connect with elements of nature – in our case, the bees – to find a way out of the city and into a nature that is somehow seen as separate from ‘the city’ and our urban culture.

So where do the bees come into play? Did you experience a discrepancy in terms of how the river, as a border, limits the movement of bees yet expands human imagination?

Johanna: There was one conversation that Marcell had with a beekeeper living between Narva and the sea, in a seaside village called Jõesuu. Marcell can speak Russian, so he was talking to the beekeeper, and we also asked this question, namely, whether he thinks that the bees actually go over to Russia. It was more like a reflective question, on the one hand, knowing that in reality bees probably can’t cross the big Narva River – they just wouldn’t manage to – but we asked anyway, just to get to know his opinion or thoughts on it. And he was very clear about it – in his perception, they go to Russia and get resources to make honey. On the other hand, it showed this way of talking about bees and the way of looking at them from his point of view.

So bees are here and nowhere, yet all around us. I think it was Monika Krause who formulated this idea that, ‘if the world is urbanising, then it must also be ruralising’. Do you think the category of ‘urban’ itself is productive in this methodology, if we see the world as a planetary, interconnected system of relationships?

Marcell: In a sense, by living an urban life – or by living a rural life – one might still rely on the same sort of things, from services to products. We definitely have to rely on nature, to which we no longer have this connection through this ‘urban’ setting we inhabit. I think, for me, it was more interesting to explore bees as messengers, and less so seeing them as a metaphor for society. To approach them as something much more, as precisely this lost relation between humans and nature. Bees are, in a way, invisible. Because starting from the moment they get out of the hive, they are gone. You don’t see them anymore. And, for me, it was fascinating to ask these people – the beekeepers – if there are any differences they have noticed. Is there a difference in how the bees behave or how the honey tastes, for instance, because it is a mediated relationship. They are like a little messenger between the ‘urban’ and the ‘outside’. Or between the ‘human’ and the ‘outside’.

In your fieldwork, did you also explore sensory experiences such as sound and taste? Did you try to map them?

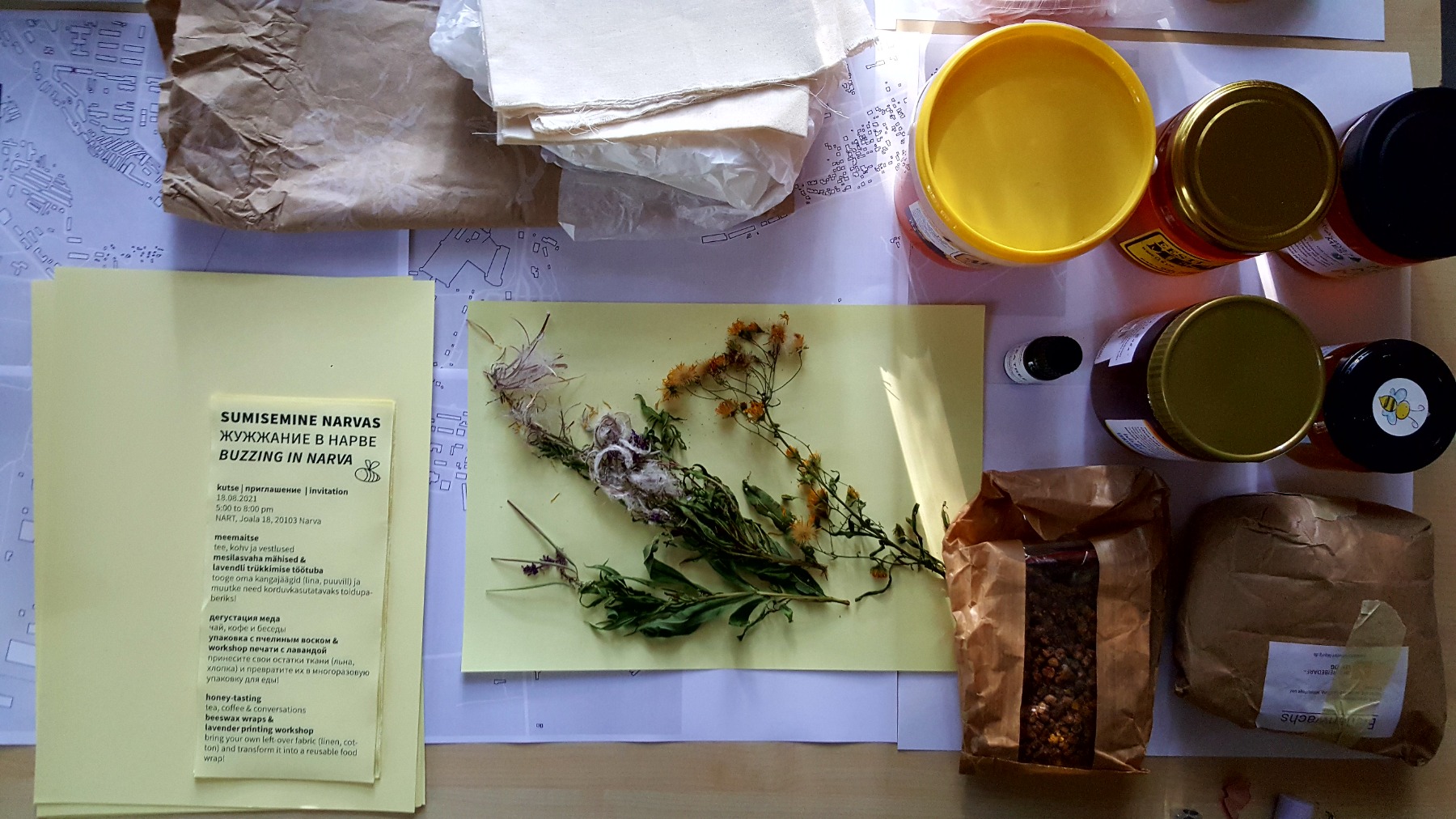

Johanna: We did not initially plan to engage with sound and taste in our exploration. Nevertheless, in the little workshop that we organised towards the end of our work in Narva, we did end up asking the question: How does Narva taste to you? How does Narva honey taste? Because we gathered quite a few different kinds of honey from all around Estonia, and we were curious about how people perceive them as well as in relation to each other. But at the end, as we approached our work very openly, these various sensory experiences were probably very formative throughout our explorations.

We tried different methods. For example, I was making more mental maps or a diary. When we arrived, we agreed that we would do these exploratory journeys or trips that we also wrote down for ourselves. Mental maps of things such as what our relationship was to the bees, what we discovered, and what was important to us. That was more of a way of documenting it for us. We also used different approaches. One day we tried to walk as close as possible to the border, trying to document it with pictures. By the end, Marcell was mapping the whole city, drawing it. In the last stage, we were putting new layers on it, things that we had discovered during our trips. We were making a map of where the beekeepers are in Narva.

And that was not particularly easy for us in the beginning because, of course, you could always look it up on the internet, but even there it was not documented if there were any beekeepers in the region, so we started to look for the markets and smaller shops in the city and asking people where we can find a beekeeper or where can we get local honey. Actually, we found that going to the small market was a part of our daily routine. It was also cute because people would say, ‘Yes, the beekeeper comes on Wednesdays’. And then we went there on Wednesday, and it turned out that the beekeeper did not show up that day. So it was a part of our rhythm, trying to find the beekeeper.

There was also another shop close to NART, a little kiosk. And there the owner also knew the beekeepers who lived around that neighbourhood, and she was also waiting for their new honey. It was always exciting to go there and buy something as a trade, hoping to get some more information. It was an interesting approach of getting cues for buying cookies or something. In the end, it was also our daily rhythm to go there.

Then we also did two or three interviews with beekeepers, and in the end, it was more about trying to connect places and spaces we found in relation to the bees, whether it’s the kiosk or the market, or the beehives we found. And then we put it all together to create a map or a new abstract map.

Marcell: In the end, it was some sort of a map. I started with drawing a very urbanistic map of the city with houses and streets and so on. And then, throughout our little adventures with the people in Narva, as Johanna described, it would change. And that flowed into our discovery of the border. Whenever we did our fieldwork, it was about following what you see, but sound and smell probably played a part in it too.

In the end, we did gather these different sorts of honey from lots of different places in Estonia, starting from Hiiumaa and through the surroundings of Tallinn to Tartumaa. So there was a list of kinds of honey and how these different places taste.

Is there a difference between how Narva and Hiiumaa honeys taste?

Johanna: A huge difference! In Narva, the honey was darker, a golden dark colour. It had a very strong taste. The Hiiumaa honey was very light, flowery even. There is also a difference in the colours of different honeys.

Would you say that the taste of honey also somehow incorporates the atmospheric qualities of the place?

Marcell: Maybe not only atmospheric qualities but ones related to the plants and the surroundings. In the end, the personal aspect of it all was especially interesting. Like, how did we get our hands on this honey? It varies hugely, whether we found it in a market or in a shop, or if we got it from a person we knew, or if we managed to find it in one of the meetings with the local beekeepers. It was very captivating for us to explore how we perceive the honey, which was very different compared to the other people in the workshop – in the end, it was a surprise to us that there is a personal aspect to taste.

Maybe there’s a link with memory. Smell has a very strong linkage with memory. In this sense, some kind of collective trace of memory possibly comes into the sense of smell as well.

I also wanted to ask you about the bees and their network. A network(ed) society. When looking at cities, this connectedness can easily turn into smartness, and it feels like it brings in more formalisation and regulation of space. Can we learn from bees as we plan future cities? Or, put differently, do you see that there is a place for disorder in cities of the future?

Johanna: In the end, we didn’t really put so much thought into the comparison of bees and human society, but on the way, we still learned a lot about social networks. Maybe it’s also simply a question of what can we learn from Narva. I found it very nice to be in Narva and to find out that these connections in the neighbourhood – like the lady from the kiosk getting honey from the local beekeeper – are still very human and alive. For example, if there is no honey left, then we just have to wait until the next harvest takes place. Maybe we can learn that we should use resources more carefully and see what nature can give us, and if there’s nothing, then we should be more careful with using it. I would be happy if more of those kiosks would exist in more cities and if there were these points where a more personal or direct connection to our natural environment is made.

Marcell: There is one thing I wanted to add that is maybe connected with what you said, that these bees are everywhere, yet you don’t really see them around you. And I think there was an interesting parallel in Narva. In spatial terms, I was very interested in seeing that next to these socialist-period buildings there is this in-between space that is not as controlled as in, let’s say, ‘smart cities’, but there are little trails. And when using these paths, you don’t really see where they’re going or where they lead to. The people who are there know where they lead. In a sense, it’s a little like flying in and flying out of the house, without the public space directly telling you where to go. So in my mind, there is this interesting parallel between, on the one hand, bees flying out of a hive and getting lost from our sight, and this not-yet-ordered nature of post-socialist public space.

And I think it’s also connected to this small-scale informal economy where we can just go to these old ladies in the market, buy local produce, and at the same time ask them about the place. Maybe it’s not good to romanticise these things because it probably stems at least partly from a lack of resources.

Will you continue exploring honey in other projects?

At the moment there is no specific destination of where to go to or a set plan, but it would be nice to continue with this research.