The Collection As a Dialogue

An interview with Greek art collector Dakis Joannou

15/05/2014

“It's all connected: your personal life, your family life, your business. I mean, everything is integrated. And obviously, if you are a collector, art is also integrated into the whole package that makes up the personality,” says the Greek art collector Dakis Joannou when I ask him whether he agrees with Damien Hirst's statement that the collection is a map of the collector's life. “Damien put it in nice, simple terms,” he adds with a smile. The British newspaper The Telegraph once called Joannou “Greece's equivalent to Charles Saatchi, only less sensationalist”. We meet in Joannou's office in the Marousi district of Athens. At first glance, the interior really does look a bit like the visualisation of a map of a life, with one wall resembling a collage of episodes from that life, covered with everything from corporate photos to snapshots of Jeff Koons' Balloon Dog, pictures from exhibition openings, family photos, newspaper cuttings, etc. I've arrived 15 minutes before our arranged time, but Joannou's secretary tells me he's already waiting for me. As he welcomes me, he conjures this feeling with such elegant ease that I even believe it. Joannou has a strong, slightly penetrating gaze; his eyes light up with kindness and humour and an unmistakable self-confidence. He is not overly verbose, and one cannot slacken while holding a conversation with this man. Having placed his cup of espresso atop a stack of art books, Joannou at first speaks very directly – he does not like the question-and-answer format, and therefore he would prefer that my article not follow a traditional interview form. “I know my words do not look good on paper. Maybe it's dyslexia. I don't know,” he laughs. But these are the rules of the game, and I must accept them.

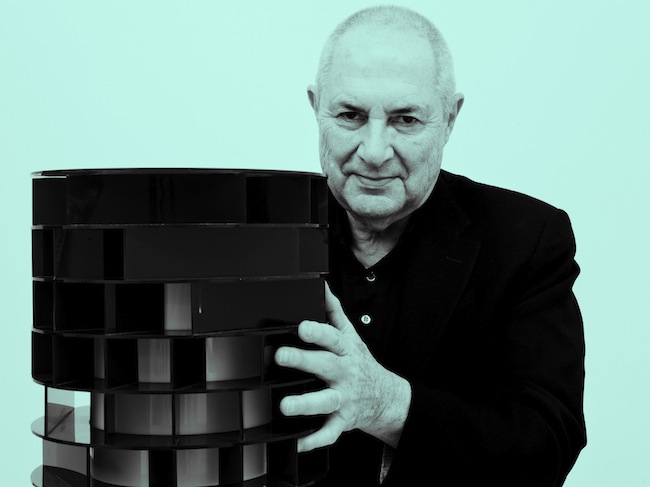

Dakis Joannou. Photo ©TOILETPAPER

Joannou is a little over 70 years old, and his name can be found in ArtReview's Power 100, a list of the world's most influential figures in the art world. Last year he was ranked #37, and he's been on the list every year since it was formed. Born in Cyprus, Joannou studied engineering in the United States and later studied architecture in Rome, after which he joined his family's construction business. The company, J&P Group, was established by Joannou's father in 1941 and has since grown into a global empire. Joannou is the chairman of the board at J&P Group but also owns shares in more than 20 other companies ranging from the shipping sector to tourism to real estate. He is a shareholder in one of the largest distributors of Coca-Cola products in 27 countries, including Greece, Russia and Nigeria. He owns the YES! network of boutique hotels, which includes Semiramis (designed by Karim Rashid) and New Hotel (designed by the Brazilian design company Campana Brothers) in Athens.

Back in 1983, before be began collecting art, Joannou established the DESTE Foundation for Contemporary Art, a non-profit that organises exhibitions and publications with the goal of popularising both known and unknown artists. “I've always been interested in art, and it was important for me to be involved in a dialogue with the processes of contemporary art,” he says. Since 2006, DESTE has been based in a former stocking factory. The foundation does not have a permanent exhibition and is open to the public only during exhibitions. This summer DESTE will devote its space to photographer Juergen Teller (June 20 – October 29).

The DESTE Prize was established in 1999 with the goal of supporting contemporary art in Greece. It is awarded once every two years to a Greek artist living in Greece or abroad. In 2009 DESTE opened an affiliate, called DESTE Project Space Slaughterhouse, in a former slaughterhouse on the island of Hydra. Every summer it invites individual artists or artists' groups to create special projects and serves as a space for contemporary art exhibitions. Slaughterhouse has collaborated with Urs Fischer, Matthew Barney, Maurizio Cattelan, Doug Aitken and others; this summer it will feature Paweł Althamer (June 23 – September 29).

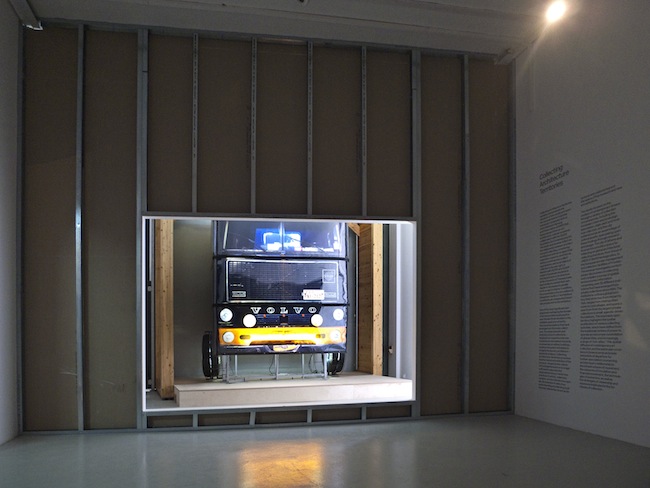

Monument to Now exhibition view. DESTE Foundation, Athens (June 22, 2004 – March 6, 2005). Photo: © Fanis Vlastaras & Rebecca Constantopoulou

destefashioncollection is another separate branch of DESTE, and it has already presented eight fashion/art projects. “Fashion is not art. Fashion is fashion. There is no other description for it. But what interests me about it is its ability to serve as a bridge between various expressions of culture (art, cinema, music, poetry),” says Joannou. It is possible to reach a wider audience through the language of fashion, he states. But he contemplated the best way to accomplish this for almost 20 years, since he noticed an issue of ArtForum with an Issey Miyake model on its cover in 1992. Then, in 2007, at a meeting with the Parisian M/M design company he came upon the idea of not creating a separate fashion show, but instead inviting a curator (artist, poet, director, etc.) to choose five items from that year's fashion scene and integrate them into his or her art. A part of the whole concept is that the curator must also justify his or her choice of items. “You connect them in some way, but you still have a clear line: this here is fashion, and this here is art. But you connect them, because the one draws from the other. In this case, the art draws from fashion,” explains Joannou. Of course, almost every artist has stepped over these boundaries in his or her own way, thereby making the process even more intriguing. For example, Juergen Teller chose vintage items instead of clothing from new collections. His project was first opened for public viewing in 2012 in the display windows of New York City's Barneys department store. This summer all eight capsule collections will be exhibited at the Benaki Museum in Athens (June 26 – October 12).

Monument to Now exhibition view. DESTE Foundation, Athens (June 22, 2004 – March 6, 2005). Photo: © Fanis Vlastaras & Rebecca Constantopoulou

Several thematic exhibitions have also been dedicated to Joannou's own collection: Skin Fruit at the New Museum in New York City (2010), Dream and Trauma at Kunsthalle Wien in Vienna (2007) and Translation at Palais de Tokyo in Paris (2005). The most recent, whose name was inspired by well known French thinker and consumerism analyst Jean Baudrillard's work The System of Object, could be seen last year at the DESTE Foundation in Athens. The exhibition spanned the whole spectrum of Joannou's collecting interests – from art to design to fashion – and its layout resembled a labyrinth full of cultural symbols governed by a global-network-like chaos and density of information.

Joannou is also a trustee of New York City's New Museum. He is a member of the Solomon R. Guggenheim International Director's Council, a member of the Painting and Sculpture Committee of MoMA and a member of the Tate International Council. He and his wife, Lietta, have been married for over 40 years, and they have four children and eleven grandchildren.

Jeffrey Deitsch, Joannou's long-time advisor and former Los Angeles Contemporary Art Museum director, once described Joannou in an interview with The Wallstreet Journal as “completely unique and really unlike any other art collector today”, because for him collecting began as an “intellectual project”, as opposed to many other collectors who began buying art, for example, to decorate their homes or just for the sake of collecting. When asked whether he agrees with this statement, Joannou says that every collector has his own path. “For me, one element that is extremely important is the relationships with the artists. Getting to know them, getting to understand what they are doing, being involved with them. Being friends with them. The social element. In fact, sometimes I think collecting is almost a by-product of the relationships. I ended up becoming a collector through relationships, by meeting Jeff Koons, Ashley Bickerton, Peter Halley and other artists, by being friends with them, by getting their work, and I became a collector without even realising it.” Joannou says that the way in which he began collecting also most precisely describes how he views collecting as a whole: “It's really about understanding and relating with the artists. And the source of the creativity. I really want to be at the source of the creativity.”

The System of Objects exhibition view. DESTE Foundation, Athens (May 15 – Novemeber 30, 2013). Photo: © Fanis Vlastaras & Rebecca Constantopoulou

Jeff Koons' One Ball Total Equilibrium Tank is considered the official beginning of Joannou's collection. He bought this work, which consists of an orange basketball suspended in a tank of water, in 1985 for 2700 US dollars at a gallery in New York City. Back then, Koons was nowhere near as famous as he has been in recent years. Joannou says that in 1985 he just bought a piece of artwork. “I didn't plan on collecting,” he says. Even though the piece of art didn't cost a fortune, he nevertheless asked for it to be reserved and expressed a wish to first meet the artist. Later, he and Koons had a long conversation in Koons' studio. “And since that time we've been friends.” And very good friends at that. As an aside, Joannou is even godfather to one of Koons' children, and Koons designed the cake for Joannou's daughter's wedding. Depending on the source, Joannou owns between 30 and 40 pieces of artwork by Koons. “I don't know. I have a piece from each of his periods.” These include the legendary Balloon Dog, a sculpture of which Koons made five variations in the 1990s. The billionaire Steven A. Cohen owns the yellow version, the Los Angeles collector Eli Broad owns the blue version, François Pinault owns the magenta one, and Joannou owns the red sculpture. The fifth “dog” used to belong to the publishing magnate Peter M. Brant until he sold it last year at Christie's for 58.4 million US dollars, the highest price ever paid for an artwork by a living artist. When I ask Joannou what is the most recent work by Koons that he's bought for his collection, he laughs and says it's a “play dough” work he promised to buy back in 1996. “I'm still waiting for it. It's been almost 20 years, but it really seems like I'm finally going to get it.” The work is almost finished, and it will be exhibited at this year's Whitney Biennial.

The System of Objects exhibition view. DESTE Foundation, Athens (May 15 – Novemeber 30, 2013). Photo: © Fanis Vlastaras & Rebecca Constantopoulou

Information about the size of Joannou's collection differs. It is estimated that his collection contains more than 1500 pieces of artwork by 400 contemporary artists. “I don't count in that way. I have lots of everything: drawings, portfolios, paintings, sculptures, large and small pieces. Museums may have a list of all of the artwork in the museum's collection, but my approach is different. Every once in a while I look over all of the artwork I own and choose 400 – 500 pieces, and those then are called my collection. The collection is constantly changing; I take something out, I replace it with something else. I play around. But, if we're talking about how many pieces of artwork I own, it's incomparably more.” In addition, he still remembers each one of them. But he also admits that meeting the artist can sometimes ruin an artwork: “Sure, that can happen. Absolutely. Sometimes you see the work and you think it's interesting. And then you meet the artist and suddenly you realise that he is not able to say anything. I'm not speaking about the artist's personality, whether he's a good salesman or not. That's easy to see, whether he's just selling something or whether there's depth to his words. People say words have an ability to influence – a good speaker can persuade you. I don't agree. An artist may not talk a lot, but it's fascinating to meet him. And whatever you discuss with him and talk about with him in an informal way may be fascinating. Other artists are very talkative. It doesn’t matter. An artist doesn't have to be, so to say, really eloquent about his work. But meeting the artist is important. It's really about understanding and about relationships, not about words.”

The System of Objects exhibition view. DESTE Foundation, Athens (May 15 – Novemeber 30, 2013). Photo: © Fanis Vlastaras & Rebecca Constantopoulou

Energy is most important. “The energy created when you meet an artist. The energy the artist has put into his work. That's a very complicated process, but it's also very important. Especially for new artists, those who have no history – you cannot understand their work from just seeing one example of it.”

Even though Joannou owns artwork by “loud” names as well as artwork by many young and not so well known artists, he cannot stand the word “to discover”. But he's nevertheless said to possess something of a Midas' touch in relation to the subsequent careers of artists represented in his collection. “That's part of the process. The piece of artwork has somehow made it into your field of vision; maybe a friend or another artist has mentioned the particular piece of artwork. You become interested, and you try to meet the artist and talk to him or her about it. It has nothing to do with discovering. I'm not a scientist,” says Joannou. That would be just as foolish as arguing about whether or not it was Peggy Guggenheim who discovered Jackson Pollack. “Peggy was undeniably one of the first collectors to appreciate Pollack, but she didn't discover him. Just as Christopher Columbus did not discover America. He didn't even know it existed. But there it was, and Columbus was simply the man who somehow found her.”

The System of Objects exhibition view. DESTE Foundation, Athens (May 15 – Novemeber 30, 2013). Photo: © Fanis Vlastaras & Rebecca Constantopoulou

But it's true that an artist must in any case become noticed. And the question of how to be noticed is one of those existential games of life/luck that preoccupies so many people. Especially on the so-called periphery of the global art world, where a visit by an influential collector is a big event. “I don't think it's really about meeting a collector or somebody who will promote him. What is important is the structure of the art world, and it's important to be inside this structure. I mean, you cannot work by yourself in the middle of Africa, talk to nobody, know nobody – no matter how good your artwork, no one is going to know about you. The art world structure can really push you up, even if you are not so good – but for how long? One year, two years, then you'll be forgotten. The structure may not be able to bring you to the very top; but if you are really good and really solid, eventually the value will appear and you'll get into the position you deserve. I mean, time is the judge of everything. It's not you or me or anybody else. It's not the critics or the gallery owners or whatever we say. Time will sort things out. Time is the only judge.”

Speaking of time, a more and more topical issue is the debate about how many of today's contemporary artworks that have been bringing record prices at auction will stand the test of time. Some believe that many of the works people are so passionate about today will turn out to be historically insignificant. “It won't even take a hundred years,” laughs Joannou. The stage “cleans itself” in just a few years' time. When I ask whether this pertains to his own collection as well and the value of particular pieces in it (considering that he's already been collecting for more than 30 years), Joannou says that it's not as if any of his artwork is less good. It's just that the times have changed. “Some artists lose energy or change lifestyles; maybe they establish families or become teachers. Some are pumped dry by their galleries and suddenly their balloons burst. Undeniably, some artists are better than others, stronger than others. But deep down they're all sincere in what they do. That's why it's not important for me to collect masterpieces. I don't consider that a collector's task. For me, it's important that the collection breathes, that it's fresh, even if some of the artists represented in it are not of the so-called highest rung. Because even those artists have something to say, and their works are truly interesting. I think that's the only way to achieve perspective, an overview.”

Fractured Figure exhibition view. DESTE Foundation, Athens (September 9, 2007 – July 31, 2008). Photo: © Stefan Altenburger

Joannou says he's never been interested in art as an investment. “Of course, over the years some of the art I own has become very valuable. But I didn't know that would happen.–. When the New Museum showed pieces of my collection in NY some mentioned that it was about trophies (and there was only one Koon’s work!). What was I to do? Apologise for making the right choices 30 years ago? (Laughs).” Joannou is speaking about the heated debate surrounding the Skin Fruit exhibition of his collection at the New Museum, which was curated by Jeff Koons. At the time, Joannou was reproached for exploiting his position as a trustee of the New Museum to raise the value of his own collection. In addition, he invited his friend – a popular artist whose professionality for curating is questionable – to curate the exhibition. On the other hand, the museum was reproached for exhibiting artwork by so-called A-list artists (Mike Kelly, Cindy Sherman, Urs Fischer, Charles Ray, Chris Ofili, Takashi Murakami and others), which flatly ignored its “anti-mainstream” concept. The New York Times' review stated that the exhibition resembled an auction display whose members “nearly all emanate from one stratum of the art world: the one where the money is”. Joannou himself called this storm of passion, which, it's true, lasted only a short while, a “contemporary apocalypse”. When asked about the pronounced commercialism of the art market, to which apocalyptic attributes are also ascribed, he says: “It's bad. And it's bad for everyone: for art, for the artists, for collectors. It's only advantageous for the auction houses and galleries. And maybe a few artists who make a lot of money that way.” Joannou believes commercialism has robbed artists of the greatest luxury – time. Time to think, time to take stock and leisurely consider their next step. “Instead, they're already pushed towards the next exhibition, and then the next and the next. Or else, three exhibitions in three cities. There is no way anybody can produce so many ideas so quickly. This is the biggest damage done by commercialisation.” How far can it go? Joannou has no idea. “I don't know. I'm not a part of it and, to be honest, I don't worry too much about it.” However, the market value of artwork – not only Jeff Koons', but also that of other artists represented in Joannou's collection – has increased immensely in recent years. “It's obvious, and you cannot ignore it. Especially if the value has increased from a few thousand to a couple million. That's a fact,” says Joannou.

Fractured Figure exhibition view. DESTE Foundation, Athens (September 9, 2007 – July 31, 2008). Photo: © Stefan Altenburger

What determines the price of a piece of artwork? “Two things: value and price. The first does not change; the second changes.” But what shapes the value? “The value is in the piece of artwork. And this is assigned by the artist. The price is the market. The price can be high or low. But the real value of a piece of artwork is here (points to his heart).” But maybe the real value of an artwork is the amount someone is willing to pay for it? “That's the price.” But isn't the price linked to value? I continue to question Joannou, even though he seems to not want to expound on this issue. “No. But it should be linked. The price and value should agree.” And what's the situation like today? “Sometimes the two agree, but other times there's a complete lack of balance between the two.”

In 2009, the Untitled self-portrait by Martin Kippenberger (in which the artist depicted himself as a hunched-over and evidently aged man in huge white underpants holding two yellow balloons that seem to raise him upwards), owned at the time by Joannou, sold at Sotheby's Contemporary Art Evening Auction for a record price of 4,114,500 US dollars. It is believed Kippenberger was inspired by a photograph of Picasso in a similar state, and it is said the balloons symbolise an escape from old age but also serve as a metaphor for the burgeoning art market of the 1980s. Self-portraits by Kippenberger are rare and therefore especially desirable. When I ask Joannou why he decided to sell this painting, he answers, “It's a fantastic painting. But, you know, there are pieces that I've spent a lot of time with, including displaying them in every exhibition I've organised. And then there comes a time when you realise you need to give the artwork a new life. Besides, I'm now interested in other things, artists of the new generation, such as Roberto Cuoghi, Urs Fischer, Pawel Althamer, Andro Wekua, Paul Chan and others.” Does that mean that in his view Kippenberger exhausted himself, gave all he could? “No, this piece of artwork was still able to give me very much. But I've turned my attention to other things now. I wanted to change the accent in my collection a little bit. Some people may have unlimited resources; I don't. I sold the Kippenberger and bought something else. That's only normal. Life goes on.” When I remind Joannou of Peggy Guggenheim's grumbling in her autobiography about making the biggest mistake when she sold her artwork by Pollack, Joannou just laughs. “Why is that a mistake? Maybe it seemed like a mistake to her personally, but her Pollacks ended up with someone else and thereby gained new lives. It's the piece of artwork that's important, not the owner.” The Kippenberger self-portrait is not the only piece of artwork Joannou has sold. He has also sold artwork by Donald Judd and Ed Ruscha – all for record auction prices.

Fractured Figure exhibition view. DESTE Foundation, Athens (September 9, 2007 – July 31, 2008). Photo: © Stefan Altenburger

When asked how he trained himself to separate good art from bad, Joannou smiles: “When you look at the piece, you kind of picture yourself 50 years from now and just wonder – will I still want to look at it? That's one test (Laughs). Will it be relevant 20, 30 or 40 years from now? That's an important element.” Joannou does not deny that collecting can also be a sort of game. “A game for adults.” And the ego also plays a role in this game. People like to own things: “This is definitely an element of it, that cannot be denied. But, you cannot turn yourself into a prisoner, a junkie. You need to be free. There are some things you will never sell, some things you'll sell and later regret, and then there are things you will be happy to be free of. But, in the deepest sense, it doesn't make any difference; it's only a part of life, the order of things. Kippenberger and I were good friends. He visited me many times, and he attended our exhibition openings. And I still own one of his masterpieces.” Joannou says he's never participated in the running amok for trophies and only very rarely has he bought artwork at auctions – only about ten pieces of artwork in total. “You don't receive what you've been craving. You lose, and another person has won. But eventually you'll get something else. Collecting is a passion, not dependence.”

Joannou is also famous for constantly moving his artwork around, whether it's at home or at the office. He says he just finished his new “exhibition” at home and invites me to come over the next day to see it. It contains a wonderful work by Maurizio Cattelan and a completely new work by Urs Fischer. A whole separate room in his private gallery is devoted to Roberto Cuoghi. “That's just in my nature. It's important for me to always be able to look at a variety of things.” And Joannou manipulates with these things like an illusionist, knowing full well that the viewer's reaction to a piece of artwork changes drastically depending on where he or she sees it. “I have a small drawing by Jeff Koons; it used to be in the bedroom of my New York apartment. Now it's the first thing you see when you cross the threshold of my house. This piece of artwork has completely changed. Not in value, but in its feeling. In other words, you have two possibilities: to see the small Koons drawing stuck in a corner, or to see a masterpiece as you walk in the front door. I like to play around with these feelings, and that brings me enjoyment.”

Monument to Now exhibition view. DESTE Foundation, Athens (June 22, 2004 – March 6, 2005). Photo: © Fanis Vlastaras & Rebecca Constantopoulou

Joannou not only moves pieces around; he also directs relationships – the way one piece of art forms a dialogue with another. Joannou's house is located outside central Athens in a quiet area surrounded by contemporary architecture. The geometrically laconic, white façade of his house stands amid blooming trees and fits right into the landscape. Marcel Duchamp's iconic Fountain used to stand in the place where Koons' small drawing now hangs. Nearby, by the staircase, is a work by the American conceptualist Allen Ruppersberg – a white piece of paper on which is written “If I find out who you are, I will kill you”. There is a brown doormat with the inscription “The Collectors” by the staircase to the lower-level gallery. It seems Joannou does not lack a sense of humour. As the exhibition in the lower-level gallery is changed, so is the interior design of the whole house. The present exhibition was created in collaboration with Massimiliano Gioni, the director of exhibitions at the New Museum and the curator of the last Venice Art Biennale.

When I meet Gioni a couple of weeks later for an interview in New York City, he tells Arterritory that he and Joannou are friends. They met in 1999, when Gioni interviewed the art collector: “We started a dialogue and it is ongoing. I often work with his collection – he invites me to think together about how to install it, in which direction it should go…. It has always been a relationship based on friendship. I am not a consultant or advisor suggesting 'buy this' or 'sell that'. I am advisor as a friend. And friends can exchange opinions and advice.”

One of Gioni and Joannou's projects together is 2000 Words – artists' monographies that are being published through DESTE. Gioni often helps to arrange Joannou's exhibitions, both at home and at the DESTE Foundation. “And that is fantastic, because as a curator in the big American institutions (museums) you can do a show every four or five years. In one sense, it is great that you have the time to think and to do research, but you have limited access to the joy of exhibiting works. And, you know, in a way, with Dakis [Joannou] it is a 'dream gymnasium' – every year we try very different things in a very pleasant places.”

Monument to Now exhibition view. DESTE Foundation, Athens (June 22, 2004 – March 6, 2005). Photo: © Fanis Vlastaras & Rebecca Constantopoulou

The first hall in Joannou's home gallery is like a small poem – Cattelan's pigeon sits on the wall, and Fischer's gigantic horse stands under it. It's a completely new work, created in 2013. “What makes Joannou special as a collector is the idea of artwork as companions with whom you live and try to understand them more and more through the act of displaying them,” says Gioni, adding that even though Joannou is very wealthy, he has never been interested in art as a status symbol. “He is a collector who is very close to the artists. He is interested in following the artist from when he or she was young and then continue on.… And this is very special, because it is not about trophies; it is about objects that encourage us to think, about looking again and again and trying to see what happens when you change something. For example, see what happens if you put a work by Jeff Koons near the work of a young artist.”

The main hall of Joannou's private gallery is devoted to Roberto Cuoghi, and at the centre of the hall is a monumental installation that was exhibited last year at the Venice Biennale as a part of The Encyclopedic Palace, an exposition curated by Gioni. Cuoghi himself installed the work in Joannou's home. The artist recently underwent a serious operation, and this experience was transformed into several of his works of art. A row of little grey boxes with sandpaper-like surfaces is placed on laconic aluminium shelves along one wall. As a box is opened, an imperceptible dust remains on the fingers like a stamp. Within each of the boxes is a piece of the artist's recent hospital experience – the outlines of surgical instruments that Cuoghi has turned into cookies.

Joannou does not only collect art. Another of his passions is furniture, namely, furniture of the so-called Radical Design period that is classically associated with the year 1968. Together with Cattelan and his legendary Toilet Paper, he is currently creating a book about the topic. The book will also include Playboy photographs from the 1960s. The living room in Joannou's home reflects the true essence of this period of design. Here we also find the iconic plastic Boomerang Desk (1969) by Maurice Calka. The bright red desk has been transformed into an improvised bar. Back in the day, it was made famous by French president Pompidou, who dared place a white version of this very same desk inside the Baroque-style Élysée Palace. “I consider 1968 to be the most innovative and most radical period in furniture design, because it was truly a turning point in the history of design, the beginning of a new era,” says Joannou.

By the edge of the swimming pool, with a picturesque view of the green hills of Athens, resting its boney breastplate against a grey concrete mirrored table with one leg bent in a model-like pose, Urs Fischer's Skinny Afternoon gazes at its own and the house's reflection. The eternal Narcissus, in his self-love he has not noticed that time has long passed on. In the distance, Mapplethorpe's and Herb Ritts' photographs of ideal bodies are displayed in the fitness studio, which has evidently been created for the opposite effect, namely, that working out and sweating leads to full enjoyment of the time one has been given in this life. “Tomorrow is cancelled,” shouts the black “road sign” by David Shrigley on the back of the door.

Monument to Now exhibition view. DESTE Foundation, Athens (June 22, 2004 – March 6, 2005). Photo: © Fanis Vlastaras & Rebecca Constantopoulou

When I ask Joannou whether it's important for him what happens to his collection after his death, he answers that he doesn't think about this issue very much. “A collection cannot be separated from its collector. When he is gone, so is the collection. There's something else in its place. Do you know the Whitney Collection? The real Whitneys? Does anybody remember the collection now?” Joannou has never fostered the ambition to open his own museum or to buy artwork in order to later donate it. He believes there are only a few such successful examples. One of these is the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia. Albert C. Barnes, a chemist who became very rich in the 20th century by developing a treatment for gonorrhoea, intentionally turned his collection into a cultural institution and later bequeathed it – in exactly the same way it had been displayed – to the state. Another example is the Frick Collection in New York City, located in a building that once belonged to the American industrialist Henry Clay Frick. It is currently a public museum, and the exhibitions there always have some connection to the Frick Collection. “I don't know of any other successful models. Well, maybe the Getty Museum in Los Angeles. Even the DIA [Detroit Institute of Arts] is constantly changing – something is being sold in order to buy something else. People in the future probably won't be able to recognise the original DIA collection anymore. Maybe they will. In any case, only a few collections have managed to remain unchanged over time.

Joannou was also at the “birth” of the Bilbao Guggenheim Museum when he was the President of the Guggenheim International Directors’ Council. When I ask him whether he thinks the Bilbao Effect could be repeated anywhere in the world today and whether such a model can even be considered current in today's context, he says: “That was a very thought-out and deliberate project that grew out of the cooperation between the Bilbao city council and the Guggenheim. One of the goals was to attract tourists, and within a year's time their numbers increased from nearly zero to 1.5 million. That was a huge achievement. In addition, they had calculated beforehand exactly the type of people who would head there. Not only people close to the art world, but many went to Bilbao just to see the building. There were even charter flights from England. The Guggenheim was aware of this, and the project was planned in this way precisely for that reason. But the art world has changed since then. The art crowd has become more sophisticated now; they only go where they want to go. And they are going for the art. You really have to be relevant. If you are not relevant, the people will not come. Of course, when Abu Dhabi finishes those very fancy museums [the extravagant Saadyat Island project], people will go there just to see them. The same way they went to Bilbao.” It is success as museum will be determined by its program.

Fractured Figure exhibition view. DESTE Foundation, Athens (September 9, 2007 – July 31, 2008). Photo: © Stefan Altenburger

Joannou's team of advisors and employees call him a visionary, stressing that dialogue as a form of communication is fundamental to all of his projects, not only in relation to art. He listens to people, but he also knows very well what he wishes to achieve. This also pertains to Joannou's hotel projects, which are no less extravagant than his art collection. Both in the case of Semiramis and New Hotel, he deliberately entrusted the creation of the hotel's image to designers who had never before worked with architecture. He invited Karim Rashid for Semiramis and Campana Brothers for New Hotel. Their task was to create a hotel as a self-sufficient entity. It is true, though, that Campana Brothers first declined the offer, and it took Joannou quite some time to persuade them. New Hotel was created on the site of a former hotel and involved the work of students at the Athens University of Architecture. Campana Brothers was given complete freedom. “We created something similar to a creative studio. The result is the equivalent of a sculpture. When I first saw it, I was completely delighted.” And here Joannou can only agree. Opened two years ago, New Hotel is an irrational concentrate of ideas, details and emotions. Some of the furniture and decorative installations were made from the previous hotel's furniture. Door frames, drawers and handles all nailed together in a seemingly chaotic rhythm...these layers of the past lead the guest to believe that each blink of the eye is the beginning of a new page in a novel that one simply cannot manage to finish reading in the few nights one spends in this hotel. In addition, there's an almost unbelievable balance between the explosion of ideas and functionality, which is not common in stylish hotels such as this. Even though artwork from Joannou's collection can be found in the hotel, he doesn't believe they play a decisive role. The artwork is there just because. “The hotel itself is a work of art – as a whole.” Joannou says that they recently took a work by Jenny Holzer out of the restaurant for a couple of months because it needed a bit of restoration, but most likely no one noticed. Unlike the Norwegian hotel magnate and likewise passionate art collector Petter Stordalen, for example, Joannou does not believe art in a hotel should be an instrument to encourage people to think, to educate them or to turn their attention to issues of social inequality or the environment. “I don't occupy myself with such things. Actually, that's the viewer's thing, whether he wants to look at what I've displayed and be enriched by it or not. I don't worry about that. I don't think it's my duty to educate and change people. That's what schools and educational programmes in museums are for. I'm not a museum. I do what I feel I need to do – to be linked to art and take part in cultural processes. I don't want any additional responsibility on my shoulders at all. For a very simple reason: to keep me free. When putting responsibility on yourself, you are not free anymore. You are bound to your responsibilities. Freedom is the biggest luxury I have, and I didn't want to give it up.”

Fractured Figure exhibition view. DESTE Foundation, Athens (September 9, 2007 – July 31, 2008). Photo: © Stefan Altenburger

Joannou owns a yacht called Guilty that has been painted by Jeff Koons in bright geometric designs and resembles a pop art object. Why is it called Guilty? “That's a complete coincidence.” Joannou noticed a Sarah Morris painting by the same name in an auction catalogue and bought it. “I thought that was a perfect name for a boat. And that's it.” The boat itself is a definite conceptualist in its niche. “Nowadays all yachts try to be like Formula 1 cars. They move only as fast as a pedestrian, but everyone's carried away by aerodynamics.” That's why he and yacht designer Ivana Porfiri decided on a radical approach. They used a classic, absolutely flat yacht platform and added all of the functional elements, such as a living room and so on. They planned each space as large as it needed to be. “In the end, the boat looked like a container.” When discussing colours with Koons, both came to the conclusion that, for example, grey looks like an ironclad warship. Then Koons remembered a photograph of British camouflage from World War I. “When he showed me that on the Internet, I said it was a fantastic idea! And I asked Jeff whether he'd be willing to paint it. He said, 'Of course.' And that's how it happened. The form grew out of necessity, not in the name of style. But necessity demanded the style created by Jeff. Everything is linked. If you'd paint any other boat in this manner, it would look irrelevant.” Asked whether Guilty is a yacht or a piece of art, the collector answers clearly, “A yacht.”

Someone somewhere once compared Joannou to a contemporary Medici. “I wish I were, but I'm not. They were just making art. They had Michelangelo, Raphael, and they just told them, 'do this, do that.' I don't do that.” But, Joannou has supported very many artists and continues to do so both privately and through the activities of the DESTE Foundation. “Yes, but the structure is different. The structure was different then, because the artist was basically working for the Medicis or the Pope. Now it's not like this. The artists work for themselves. And we each respond to the work they are doing.”