“Art collectors are currently the main drivers of the art world”

An interview with Russian art collector Igor Tsukanov in London

02/02/2015

Igor Tsukanov, a Russian businessman and art collector living in London, is a very pleasant conversation partner. He is energetic and intelligently ambitious yet communicates very simply. On the day we meet, the British newspaper The Independent has published a review of Post Pop: East Meets West, the exhibition jointly organised by the Tsukanov Family Foundation and the Saatchi Gallery. “All of the biggest British newspapers have written about it,” says Tsukanov, and he has good reason to be pleased. The exhibition, which focuses on the metamorphosis of the language of pop art in four different geographic areas – Russia, China, Great Britain and the United States – takes up all of the floors of the Saatchi Gallery and comprises a total of 250 works of art made by 110 artists. Its curators, Andrey Erofeev (a Russian art critic and former director of contemporary art at the Tretyakov Gallery), Marco Livingston (an independent curator, theoretician and co-producer of many pop art exhibitions) and Tsong-Zung Chang (a curator and guest lecturer at the China Academy of Art), are a veritable team of stars, and the exhibition itself is one of the most prominent events in London's art scene this winter. In addition, Tsukanov has managed to launch this exhibition before the Tate Modern, which is planning an extensive exhibition devoted to pop art in autumn of this year.

The Tsukanov Family Foundation and the Saatchi Gallery have signed a five-year partnership contract, during which time they will focus on the current art scene in the post-Soviet region. Post Pop: East Meets West is already the second exhibition to take place in the Saatchi Gallery in cooperation with the Foundation. The first exhibition, Breaking the Ice: Moscow Art 1960-80, drew a record-breaking number of visitors.

Tsukanov is a so-called systematic art collector, that is, a collector who finds it important to have a definite focus for his collection. He began collecting in 2000 with Russian avant-garde paintings from the early 20th century but soon realised he could not form a distinguished collection of this period because the best works were already owned by museums. So Tsukanov decided to shift his focus to the second Russian avant-garde (1960s-1980s). His goal – which he can consider to have already fulfilled by now – was to create the most extensive art collection from this period. As Tsukanov has said in an interview, his ambition is for “the second Russian avant-garde to be included in the school books”. His collection currently consists of about 350 works of art, and he has the largest collection in the world of works by seven of the most significant artists from this period: Vladimir Nemukhin, Lydia Masterkova, Dmitri Plavinsky, Oscar Rabin, Oleg Tselkov, Evgeny Rukhin and Alexander Kosolapov. His future goal is to open a museum of Russian post-war art. But this is only one of Tsukanov's activities; the Tsukanov Family Foundation has also initiated several support programmes for education and culture in Great Britain and Russia, including one at Yale University.

Our conversation with Tsukanov took place at his home in Kensington, and he told us that when building his home, he gave much thought to how art would be exhibited in it. As befits a systematic person, a logical exhibiting of art is of great importance to him.

Igor Tsukanov. Publicity photo

Yesterday I visited the pop art exhibition that you organised at the Saatchi Gallery. Do you think its ambitious plan – to unite Russian, American and Chinese pop art – has succeeded?

I didn't have a specific plan to unite artists. I had another idea in mind. My idea was to show the development of an artistic language by using examples from various countries. And the language of pop art has undeniably been the most universal artistic language in the 20th century. The way in which this language was used in Russia, China and Great Britain, where it originated in the 1950s, and then later in the United States in the 1960s, differed dramatically. In essence, the exhibition is a story about how artists living in these countries used one and the same language for completely different goals. And the exhibition was created around this language. We also specially limited the territory by examining only Russia, China, Great Britain and the United States, because if the exhibition had also included other European and Asian countries it would have become too large to successfully accomplish. But I also knew that there was going to be a pop art exhibition at Tate Modern this year and that it was going to cover more thematic territory yet occupy a space that's three times smaller than the Saatchi Gallery. Even in London it's hard to find a space as large as the Saatchi Gallery. The Tate's exhibition will be called The World Goes Pop, but, to be honest, I can't really imagine how they'll be able to realise this concept by exhibiting only groups of one or two works.

When I began this project, my idea was to create it completely differently than the museums usually do it. That's how the idea of dividing it into themes came about – not planning according to artists or countries but instead according to thematic arcs, to which then corresponding artists were found and added.

Was the exhibition's concept your idea?

Yes. You could say that my job was to be the show's producer, to use an analogy from cinema. As its producer, I came up with the concept, and for its implementation I needed a director (curator). In this case, each country has its own curator. That's a very important experience. I don't remember when an exhibition of this scale was ever created by three curators. Usually there's just one, and the exhibition is the curator's own choice, his or her vision. In this case, I – the producer – was this sole curator, otherwise the idea simply could not have been realised. In addition, there was very little time – only eight months – which is ruthlessly little time for an exhibition of this size. Similar projects usually take at least three years to organise. And, if they're made by museums, then two years are usually spent on research alone. We simply didn't have time for that. I calculated that the best professionals in their niches already know everything anyway and therefore no additional research was necessary. My main task was to create a team. The Saatchi Gallery helped very much in this regard, and in certain cases we conducted negotiations through them, because it was critical to have people agree to the project. For example, Marco Livingstone, who is the curator of the exhibition's Great Britain section, is a respected professor of art history, a distinguished and very serious person. It's quite complicated for him to involve himself in new projects, also from the perspective of his reputation. Our negotiations were very long and complex. At first he turned the project down, then he agreed to it, and then he declined again. But we came to an agreement in the end.

Did any of the artists decline to have their work exhibited?

That's an interesting aspect. Regarding the British and American section, you could say that we accomplished about 60% of what we had planned. There were two problems. Firstly, it was extremely difficult to get works by certain artists. Especially Jeff Koons, because he had two big exhibitions going on at the same time – the retrospective at New York's Whitney Museum, which then travelled to the Pompidou in Paris. At first, the Gagosian Gallery, which represents Koons and with whom we negotiated, agreed to lend us the works, but then it declined on the grounds of the retrospective, the client's wishes, etc. As a result, we found Koons' artwork in a completely unexpected place in Mexico. It was just as complicated with Richard Prince.

In short, it was extremely difficult to get works of art from several artists whose work was critical for the exhibition. With other artists there were other issues. A British artist, whose works we very much wanted to include in the exhibition and whom I also happen to know quite well, agreed right away, with the greatest pleasure, so to say. But then his gallery – a very large and well-known gallery – wrote us a letter saying that they were planning an exhibition of the artist's work for the following year and therefore refused any showings of it until that time. In other words, welcome to the art world.... In another case, the gallery representing a very well-known British artist informed us that they did not consider her art to be pop art and therefore her inclusion in the exhibition would present the wrong idea. The letter was very strange, and I later found out that there was more nuance to it than we first knew; the attitude could be traced back to the 1990s and the personal relationship between the gallery owner and Charles Saatchi. We faced such snags and hidden obstacles here and there; some we were able to resolve, but not others. In addition, our goal wasn't to bring together as many artists as possible. A hundred is too many anyway. But the most crucial names are all represented in the exhibition, although in terms of the quality of the works, I would have liked for some of them to be better. But it is what it is.

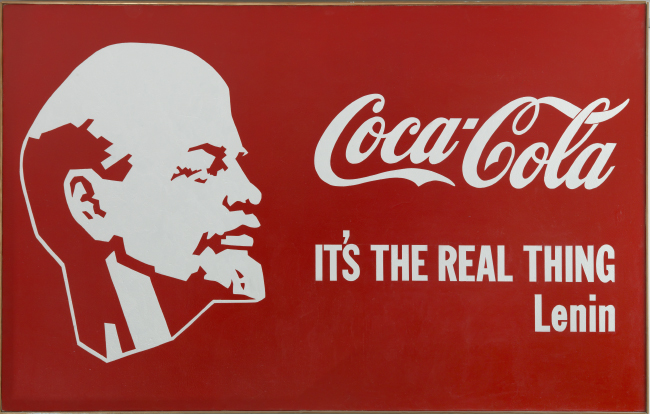

Alexander Kosolapov. Lenin and Coca-Cola. 1982. 117x188 cm. The Tsukanov Art Collection

The first exhibition you created together with the Saatchi Gallery, Breaking the Ice, was phenomenally successful, with over 600,000 visitors in three-and-a-half months. How do you explain its success? Did the visitors really go to see Russian art?

There's one essential thing here that not everyone understands. Because I come from a different background and have worked as a researcher as well as businessman and financier, I have my own outlook on many things. Therefore, when I entered the art world not only as an art collector but also with the desire to create exhibitions, I approached this process differently than many others. A few basic things were important to me. Firstly, no matter how good the content of an exhibition, if you create it in a small space and a place that does not attract attention, you're only going to reach 10% of the potential audience. Kind of like art-house cinema. The films themselves are good, but they cannot reach a larger audience than that at a small club or festival. Secondly, in addition to the importance of the right place, an art exhibition will attract attention only if is thematically strong. It's got to be a show. So that people who go to it see its development. It's important to bring the exhibition to the mass media and its possibilities. Very few producers of art exhibitions do that, even among the large art institutions. Thirdly, you need volume. Mainly financial support, because it's often a lack of money that prevents people from doing all that they've planned. Then you start making compromises, and once that happens it's a different story.

When we were creating Breaking the Ice, my ambition was to create the largest exhibition in history devoted to a single period of time. The 1960s-1980s were a unique period, and it will never be repeated. From that perspective, it was a purely historical exhibition. And I'll never make historical exhibitions again, because they're only possible once. After the exhibition I spoke with several galleries, and they admitted that there will be no more similar exhibitions in London for at least 15 years – there's no point, because it's already been done before.

But you asked about the visitors. That's an interesting aspect. Both here in London and, I think, also elsewhere, the number of visitors serves as an indicator of an exhibition's success. Everybody looks at the numbers. And there's a positive and negative side to the numbers. The positive aspect is that no matter what you do at the Saatchi Gallery, people are going to come. This is determined by the gallery's location, but also because each exhibition is accompanied by a huge marketing campaign. The question is actually why do people come? In a way, you could say that they come like waves of traffic that grow with every next larger event. That's very plain to see. In essence, you can put practically any exhibition in the Saatchi Gallery and it'll have 2000-3000 visitors per day. If it's a broad-ranging exhibition, you'll get 5000 and more visitors per day. The number of visitors is very important, especially for corporate sponsors. And, from this aspect, we can say that the present exhibition is very successful; some days we have even 7000 visitors.

How did your cooperation with the Saatchi Gallery begin? Did they look you up or vice versa?

They found me. When I decided to create the Breaking the Ice exhibition in London, I approached several galleries and museums, and I also sent my proposal to the Saatchi Gallery. At first they did not respond, and then later they approached me and said they have another proposal. They said they wanted to create a small thematic exhibition from their collection and, if I were to organise another exhibition parallel to theirs, that would be great. And that's what we agreed upon. But when it turned out that the exhibition was even more successful than expected, they approached me with another proposal, namely, they had considered everything and wanted to create a partnership with me. This means that for six years I can do whatever I want at the Saatchi Gallery focusing thematically on the countries of the former Soviet Union. The next one will be Azerbaijan. Seeing as I always want to find a new angle to things, I'll be combining it with Turkey, thereby highlighting these two situations. Georgia will follow after that, but I still haven't decided what I'll combine it with.

Can we still talk of national art in this global world of ours?

Not anymore, I don't think so. If we take a look at art history, it was national until the beginning of the 20th century, and then it gradually became international. As Paris became a sort of centre, art collectors and artists from various countries began heading there. Before that, everyone was separate: the French, the Americans, the British. Later, New York City became the centre and everybody headed there. In this sense, the art world ceased being national a long time ago. But in spite of that, both Christie's and Sotheby's still have auctions of Italian, French and Russian art that almost always also contain contemporary art. Even though national art as such no longer exists and no one really knows what it is anymore, history still continues as the result of inertia.

But, despite all I've just said, there are still, for example, very large communities of French, Italians and Russians in London. The Chinese community is now rapidly growing as well. All of these communities want to show their national artists in some way. I think that's only natural. Maybe not those who've become global stars, but those who aren't yet widely known. That's why French sponsors and wealthy French families living in London help French artists, and Germans help Germans. That's not a trait of national art; rather, it's a definite sign of support for an artist who comes from your country. And associatively, it's also a form of cultural support for your country. I think this is good, and I also do it. But, in terms of collecting art, I already made the decision quite some time ago that I will no longer create national collections. The collection I've created and which I showed at the Breaking the Ice exhibition can in a way be seen as the finishing touch. My next collection will be completely different. It'll be international, even though conceptually it'll be based on a theme, not specific artists.

Oscar Rabin. Violin at Cemetery. 1969. 80x101 cm. The Tsukanov Art Collection

Do you think you've been able to shed light on the area of “Russian art” in London? Or do you still have a long journey ahead of you in this regard?

I think that if you support cultural history in your country in the positive sense, then ethnicity – Russian or non-Russian, German or non-German – must be of secondary importance. The context in which you show these artists is much more important, so that they do not become representatives of just one country and one specific time period. So that it doesn't become art that is reined in by a specific time period and place and does not move beyond that. Otherwise you turn it into an ethnic and very limited story. That's why a part of my strategy was to show that this period at the centre of my focus and the focus of other collectors was in its way unique. Because it was a specific civilisation that no longer exists. And this civilisation gave birth to specific artists who actually worked with themes and methods that can be compared to those of European and American artists. But in their case it all took place within a different context. Many visitors to the exhibition – and critics, too – drew parallels with Vladimir Veisberg and Italian artist Giorgio Morandi. Later, I often said and also wrote that this world ceased to exist after this civilisation (the Soviet period) ended. Therefore, we can only talk about memories or evidence to leave to museums, evidence about how this world was created. But the actual world no longer exists.

There was a time when it was in style to attract Russian money for everything. How large of an influence do you think Russian art collectors had on the art market during those years? And do you think it encouraged the current increase in prices to absurd levels, similarly to the Japanese yen boom of the 1980s?

There are several levels to this topic. It's not so simple as saying that Russian money arrived and they bought something.... Russians who buy only Russian art is one thing, but Russians who buy international names is another thing. They buy trophies. Speaking of Russians who buy Russian art, the first businessmen (followed later by civil servants), who earned their money in various ways, belonged to the generation that was not very interested in contemporary art. They were about 35 years old when they began; now they're around 50 and a little bit older. The art they bought reflected their personal tastes and was mostly Russian art from the late 19th and early 20th centuries. And yes, you could say big Russian money caused prices to increase in this niche. An Aivazovsky cost around 30,000 or 40,000 dollars in the early 1990s, but by the turn of the century it already cost ten times more, sometimes even more than that. That's a classic example of how it all works. But regarding contemporary art, these businessmen didn't even go in that direction because that requires a completely different kind of perception. It can be seen even more distinctly in the case of current art, where there is no growth in the Russian market whatsoever. Of course, there are some art collectors – ten or fifteen of them – but the generation that might be ready to buy works by young Russian artists that are selling for about 10,000 to 15,000 dollars are currently not buying. You could say everybody's in a bad mood right now. And that means that these two markets are strictly separated – Russian contemporary art is one story, Russian art is a completely different story. One's got Russian money, the other hasn't.

But in general, it doesn't matter whether it's Japanese, Arab, Chinese or Russian money. When so much money flows into the art market, is that helpful to the development of art or, quite the opposite, does it hinder it?

In this case, we're not talking just about Chinese, Arab or Russian money. The one-and-a-half billion dollars that circulated in New York City's auctions alone in the past week is evidence only of the fact that individual artists have become as interesting today as airplanes and automobiles. It's become prestigious to buy their works. In addition, it's not only art collectors who buy. An art collector can also buy something much cheaper and less well known if it simply fits into his collection. A certain type of art buyer has emerged who simply buys. I know quite a few of them, and they're never going to become art collectors. For example, one of them has bought an awful lot of artwork in the last five years and spent hundreds of millions on it. He's a serious guy. When I asked him why he does it, he said he enjoys it. He says it's good for him, it's good for everybody. He's about 50 years old. He had never before taken much interest in art, but now he's such a good client at Christie's that they literally carry him around in their arms.

On the one hand, there's nothing wrong with a situation like that. But on the other hand, if 80% of the money goes to this 5% of the art market, there's hardly any money left in the rest of the market. And therefore none of the other galleries (except the very top players) benefit from it. Because the money goes off in a completely different direction and is in no way linked with the very foundation of the art market. The art market has always been very difficult and complicated, and it'll remain that way.

Victor Pivovarov. Flying Flying. 1973. 173x113 cm. The Tsukanov Art Collection

In a way, it's an absurd situation. The money supposedly helps those whose artwork is already expensive, and this raises the prices even more because everybody wants them. But the money never makes it to the people who form the foundation....

That's the way it is, and that's the way it's always been. I've been closely connected with Yale University and the Goldsmiths Art School for quite some time now, so I know their statistics quite well. Goldsmiths predicts that in ten years' time less than 10% of their graduates will be working in the field of art. But that's not the case among bankers, lawyers and doctors. Actually, these people remain near art and do something related to art, but they earn their money in other ways. If there was more money in art, this 10% figure would probably be higher. As far as I know, it's the same thing with music right now. Schools prepare too many musicians, who are then unable to find work.

It's probably also just circumstances or coincidence that makes one person successful and another not. Especially in cases like Koons, Kiefer and Kapoor.... Nobody can really say why it's precisely these artists' work that costs so much.

Of course they can't. Koons also had his ups and downs, and I doubt anyone would have been able to predict back then that his works would cost so much now. Then again, in order for something to cost so much, it needs something else – great charisma, a good story. It never happens just for no reason. Of course, Kiefer is a superb artist, but there are lots of superb artists. Yet there's a tenfold difference in the figures for which their artwork sells. This is a very complex issue and, to be honest, I don't completely understand how the system works, either. But what's more interesting is who does it benefit? For example, if the artwork by prominent artists represented by a gallery costs an average of 500,000 dollars and the gallery owner accepts works by two more young artists, it's much easier for him to speak with art collectors. See, I took on this artist and will work with him for ten years. Then art collectors listen to him. The big galleries that absorb such large amounts of money are forced to expand their circle of artists with new names. And they thereby have influence on the level of prices. Maybe it's not decisive influence, but it's influence nonetheless. But there aren't many such galleries. And it's very hard to convince those galleries that are not at this level as to why they should buy works by such-and-such an artist for 30,000 instead of 10,000 dollars. It's impossible to explain it.

Dmitry Plavinsky. Cosmic Phenomenon over Jerusalem. 2000. 150x150 cm. The Tsukanov Art Collection

I recently interviewed a well-known gallery owner who said that they do not sell art; instead, they place art. In other words, you can't just enter a gallery with a suitcase in hand....

Considering the specific character of my collection, I have not bought artwork at large galleries. They simply to not stock what I need. But I have bought art from artists, and with them that's undeniably the truth. Artists want their work to be displayed in large collections and thereby become known, etc. An artist will not sell a valuable piece of art to just anyone. He might sell another piece of art, but he doesn't want to give away those pieces that are valuable to him. Maybe that's what this gallery owner was thinking, too, meaning that he wants the best pieces of artwork to be in the best collections. At the same time, another reason, although not the main reason, is that galleries want to control the movement of art. A good art collector isn't just going to go and sell a piece of artwork; he'll mostly likely buy something in its place, too. And that's already the next transaction. Good, normal management.

You began your collection with avant-garde Russian art from the early 20th century, but once you understood that you would be unable to create a complete collection, you turned your attention to the second period of Russian avant-garde. How near or far from completion is your collection now, and what do you plan on doing with it in the future? In a few interviews you've alluded to the creation of a museum.

I'd say that if it were possible to unite three collections, then that would be the largest collection of this period in the world. My collection is currently the largest in terms of the beginning of this period, namely, the 1960s. But Vyacheslav Kantor's collection is much broader and stronger in terms of the 1970s and 1980s. He's got outstanding works by the Kabakovs and Bulatov. He's even got his own private museum in Switzerland, but that's closed to the public. The third collection belongs to the Ekaterina Foundation and is more representative of the 1980s. But uniting these three collections and forming a museum is probably just an unfulfillable dream. I'll definitely give my collection to a foundation or public space, probably right here in London.

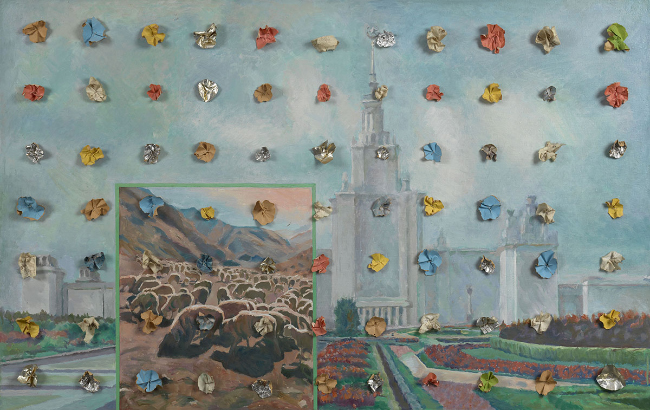

Ilya Kabakov. Holiday #1. 1988. 100x160 cm. The Tsukanov Art Collection

Better in London than in Russia?

Yes, but not because everything is changing in Russia right now. It'll continue to change. There's already too much of everything in Russia. Too many restaurants in Russia, too many museums. A good acquaintance of mine is currently building a museum in Moscow. Actually, he's almost finished. It'll be called the Museum of Russian Impressionism. I'm not criticising, but I ask him what is Russian impressionism? They're Russian artists who studied and lived in France. And now you want them to represent Russia? And what's a private museum in Moscow compared to the Tretyakov Gallery? Who will see these works of art? On the other hand, if you were to open a museum of Russian impressionism in Paris, for example, that would be a completely different story. Because the defining point would be French history, and besides, there's nothing like it in France and people from all around the world visit France. I tell you that only to illustrate the point that there is no idea in Russia to do anything like that. In London, on the other hand, I want to unite two, three, maybe more collections. So that it would become a living space instead of just a museum. But first I'll work with Saatchi for these six years and then start thinking about what to do after that.

But you consider your collection to be finished now?

You know, it's close to being finished. The problem is that I can't find anything more that would significantly increase its value. Any works I add will only be of incremental value to what's already there. And I see that very clearly myself. I was at an auction in Moscow recently where a work by Oleg Tselkov was being sold. He's one of the artists whose work I usually buy because it's fairly rare. This particular work of art, however, was of second-class quality – I have works that are much better – but even so, I would usually buy it. And that's what I did this time, too, and someone else was bidding as well. We raised and raised the price until at one moment a thought crossed my mind – maybe this is the other buyer's first Tselkov from the 1960s? He probably needs it a lot more than I do, because I already have six or seven of his works, and this one is nowhere near being the best of them. What's the use in me buying it? I realised I was buying it due to inertia, because I supposedly thought I cannot let it go, and so I stopped bidding. The other guy bought it for 120,000 euros. Afterwards, I understood that I should either quit or work on strengthening those artists in my collection that I have not yet strengthened. For example, I have three works by the Kabakovs. Very good works of art. But it's impossible to create the best collection of the Kabakovs' art, because many of their works have been bought by Abramovich and others. I could buy one more piece by them, but it wouldn't make much difference. And when I analyse this situation, I realise that I'm already close to finishing my current collection. It's better to stop it and start doing something else.

By the way, I recently traded artwork for the first time. It's a very funny story. There's a well-known art collector with a big collection. It's undefined, unfocused, so it's a little wild; it's got lots of everything. And I said to him, look, you've got very good works by Dmitry Krasnopevtsev. He was a refined Russian painter in the 1960s, very well known. I told him to create the best collection of Krasnopevtsev's works in the world and then everyone would be turning to him, museums, etc. Seeing as I had one work by Krasnopevtsev at the time, I told him, see, you've just got one work by Bulatov. What are you going to do with it? I, on the other hand, already have four Bulatovs from the 1960s. Shall we trade? And we traded – I gave him the Krasnopevtsev, and he gave me the Bulatov. I was happy and so was he. And it had nothing to do with price. If you look at market values, I probably gave him a Krasnopevtsev that was worth one-and-a-half times more than I would have paid for the Bulatov. But it didn't matter.

Oleg Tselkov. Five Faces. 1980. 200x160 cm. The Tsukanov Art Collection

Back to auctions, one time you were running after a work by Bulatov, but you were unwilling to pay 800,000 pounds for it. Later, you learned that you had unknowingly been bidding against Shalva Breus, a good acquaintance of yours.

Yes, that's 100% true. But the story has a continuation. There are two versions of Vkhoda Net, the piece of artwork by Bulatov we were bidding for. The first one is in the Centre Pompidou in Paris, which usually does not lend it out for exhibitions. Bulatov made the second one for an exhibition, and it later showed up in a Phillips de Pury auction. It's small – 1.5 x 1.5 metres – but I needed it very much because in a way it's considered a very crucial work by Bulatov. And, obviously, Shalva also needed it, because he's got a very good Bulatov collection himself.

So, an art collector approached me about a year after this auction and said that he knew that the biggest work by Bulatov, which is currently in the Tretyakov Gallery, does not even belong to the gallery. The collector himself had sponsored the artwork and it actually belonged to him. The gallery wanted to buy it from him, the negotiations lasted four years, but nothing came of it. Bulatov had made the work for an exhibition, his last work. The collector showed me all of the documents and asked me whether I wanted to buy it. I said alright, if you're able to get it out of the Tretyakov Gallery. In the end, he managed to do it, and I bought the painting. So, it turned out that I was unable to buy one of Bulatov's works, but I did end up buying another.

You've bought a lot of artwork at auction and have sometimes not considered price. What happens to an art collector at an auction? Is he also human and emotional? Are you able to retain a rational outlook, or do you feel the hunter's instinct?

I'm not a very emotional person. I don't know whether you followed the last auction of Russian art. There, a completely average work by Valentin Serov, whose starting price was one million pounds sterling, sold for nine million. There were two bidders, both very emotional Russian billionaires whom I know very well. They both knew very well whom they were bidding against, but they each wanted to show off.... And so they raised the price ten times, and the guy who finally got the piece never really understood why he needed it in the first place. But at least he knew everybody would be talking about how he outplayed the other guy.... Besides, that wasn't the first time they had entered a bidding war together. It's those guys who raise the prices. They've become a sort of joke in the art world already. Regarding myself – and I've never shied away from the fact – I used to have a fairly easy time buying art at auctions because I've always valued the specific works of art a little bit differently than those who bid against me. Besides, it's often been dealers or other middlemen who've bid against me, not the final buyers. I've always been well aware of that, and I can also feel if the person has a limited budget. As the price goes up and up, there's a moment when you can feel that the other guy's reached his limit; he needs to go call someone, find out his boundaries. And that's why I've always bought everything I've wanted. That time with Shalva was the first time someone out-bought me. And I knew right away that he was the final buyer.

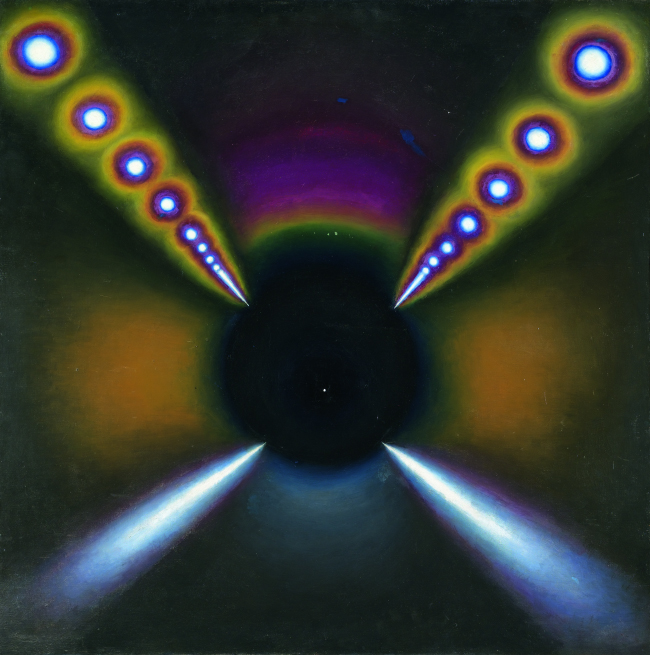

Erik Bulatov. Black Tunnel. 1964. 99x99 cm. The Tsukanov Art Collection

Why did you back down? Did you just decide that that specific work by Bulatov wasn't worth that amount of money?

In the case of the Bulatov, that was the first time I realised that the person across from me was just going to keep going further and further.... And it just didn't seem rational to me to continue. I stopped because someone who really, really needed this work of art had appeared across from me. That happens rarely at auctions. Even in the big global auctions you rarely see the initial price increase five or six times. At Christie's and Sotheby's artwork prices usually go up one-and-a-half to two times. Prices increase tenfold only in Russia.

You've also bought a Damien Hirst. Isn't that a bit stereotypical?

My wife wanted to get a few pieces of artwork for her Moscow office that weren't by Russian artists. I said OK, seeing as I was planning an exhibition of artwork that had already become a part of the mainstream in the 1990s. And Damien was like that, and Marc Quinn, too, who's also a good friend of mine. He might not be a global superstar, but he's a very good artist. To be honest, I'm still not clear about my next theme, but it's developing slowly.

So, you're ready, but you haven't focused yet?

Yes, precisely.

But surely you won't stop, will you?

It's hard to stop. This energy might be directed in some other direction. But the question is where? If business as such is no longer interesting, but a person has to do something, then art is a good thing to do.

How important to you are friendships with artists?

That depends a lot on the generation. The generation of artists represented in my collection – those who are still alive, and, thank God, many still are – are now around eighty years old. I've met with all of them, and many of them have visited me in my home; we have a great relationship because they see what I do and they like it. But there's another nuance. Just having a chat with an artist, having a drink together, so to say, is one thing. But it's a different thing if an artist allows you onto his intellectual level, when he starts talking to you as an equal. Only very few of them are able to do that. Maybe because of their education; maybe because I've studied art quite seriously I am able to talk to them about things that maybe even they themselves don't understand completely. That opens up a lot of opportunities.

But I must say that the most interesting thing for me is the time when I can talk with an artist for an hour or two about his artwork and nothing else. Besides, this generation of artists – including those who left Russia – are a very reserved bunch. They've always worked underground, in secret studios. Even when they reached the age of 30 and 40 they didn't attend art soirées, didn't agree to interviews with journalists and had no opportunity to create their own artist's images as we know them today. An artist who must also promote himself, who must know how to speak well, and so on. This generation is still a very reserved generation, and one can feel it right away in a conversation. The young artists, on the other hand, are completely different – they go to receptions, they communicate.... I meet with them, of course; I visit their studios and they even consider me a person they can learn something from that might help them in their work. They ask for my opinion. And I share generously; I'm not afraid of saying anything, and they like that. I have a very good relationship with artists. Yes, some of them might take offence regarding why I don't exhibit or buy their works. I don't buy works from a lot of artists, but I nevertheless keep up a dialogue with them, and these conversations are interesting for them.

Oleg Vassiliev. Before Sunset. 1990. 210x165 cm

What do you think is an art collector's responsibility?

I don't think that collecting art is any sort of special responsibility. An art collector is someone who has his own specific vision and view of things. He's someone who can not only separate himself from other art collectors but also from an artist's vision. If I were an artist, I would find it very interesting to find out how others view my work – not just regular viewers but also professionals who invest their money in art and who have done a great many other things in life as well. These opinions would be some of the most important for me. Of course, some artists do not agree with me. They think they can do whatever they want. And that's why I think an art collector's mission is to always be developing his own individual vision. A museum's vision is completely different. There's a saying in Russian – I live in this swamp and I praise this swamp. Maybe the fact that I'm from this “swamp” causes me to believe that art collectors are currently the main drivers of the art world. The museums will follow them. Museum workers, however, think otherwise; they believe they and their curators are the ones dictating everything. But I don't think so.

Speaking of creating a collection, museums usually buy things that are tried and true. Oftentimes when the works of art are already quite expensive. It seems that museums are afraid to take a risk and invest in art that might be interesting ten years from now.

Yes, that's the case 90% of the time. The remaining 10% may have some kind of nuances. Of course, a museum is a public space, and that supposedly has its advantages. In addition, museums always boast about being independent. But in reality they're not independent at all. I've worked with museums quite a bit and I know very well how decisions are made there. It's definitely not society making those decisions or influencing what happens in them. But museums like to think that it does.

After visiting a number of contemporary art museums in Europe, you soon begin to feel like you've already seen all of this somewhere before. As a rule, you'll always see a Picasso, a Lichtenstein, a Warhol wherever you go.... It's starting to become boring.

But there's a nuance here. The Warhols and Picassos are there not because the museums bought them but because they were given to the museums. As we know, museums never have any money. And what do they do? They turn to their sponsors. I've also bought artwork for museums. For example, the Tretyakov Gallery. How do I do it? They send me a list of artwork that the commission has approved and considered to be good. And I buy only those works of art from the list that seem interesting to me. There aren't many like that on the lists. And lots of art collectors don't find anything interesting on them at all. That's why I'm convinced that this is the way it usually happens – the museum goes to its sponsors and says it would like to acquire this or that, but the collector says I'll buy this but I will definitely not buy that.... Or, if an art collector has collected a little of everything – in the style of collecting trophies – then often these works later end up in museums. And that's how the museum collections are made.

But as soon as a museum organises an exhibition of an art collector's collection (and, God forbid, if he's also on the museum board), everyone immediately starts talking about the ethics of this process. Would the value of your collection increase if it were exhibited at the Tretyakov or now at the Saatchi Gallery?

I'm not convinced that the prices for the artwork I own would increase if they were exhibited at the Tretyakov or Saatchi. I don't see a direct link between these two things. But if we look at generally accepted practices, if collectors are offered an exhibition or to lend their artwork to a museum exhibition, they usually agree to it. It definitely benefits the collection, because museum exhibitions have catalogues, and the fact that a piece of artwork that you own has been published increases its value at auction. However, not all collectors agree to lend their works to exhibitions. For example, as I was rounding up artwork for the pop art exhibition, I was forced to turn to various auction houses, because otherwise I was unable to get them. I have a good relationship with Sotheby's, and I thought I'd make a list of ten works of art I needed and they'd ask the art collectors to whom they had sold the works. Sotheby's agreed. Three of the art collectors agreed to lend their works, but seven did not. I wondered what the seven were thinking, what was the logic behind their decisions? I don't understand it. In my opinion, collectors must lend their works and rejoice in doing so; the artists will be happy, too, because their work is exhibited. Everything should work together like that. But unfortunately it doesn't always work like that.

It is often said that art is a mirror of its time. Which of our artists today do you think best embody this statement?

To be honest, it's difficult for me to say. I can only take a guess. If we take a look at Great Britain, what kind of times can art reflect here? How does one portray a time period anyway? Probably with certain events. And often these events are political instead of cultural or economic. Powerful political metamorphoses. We might still be able to speak of such associations in the case of Russia. There was a unique feeling in the 1990s that everything was falling down, but nothing had yet taken its place. In other words, everything had already collapsed, but nothing new had been created. I associate the 1990s most with Oleg Kulik as well as with Vladimir Dubossarsky and Alexander Vinogradov. If we look at the situation today, in which the state as such is literally vanishing, this is most vividly expressed in a language of art by the Blue Noses group and Pussy Riot. They're the ones who have best and most quickly felt that everything is collapsing again. Something had been created and now it's falling down again. The effect of demolishing.