A sanctuary for art

An interview with Japanese art collector Takeo Obayashi in Tokyo

10/04/2015

There is a great variety of art spaces in the world: galleries, museums, exhibition halls, sculpture parks and so on. But Japanese art collector Takeo Obayashi's Yu-un guesthouse/gallery doesn't seem to fit any of the traditional classifications. Yu-un is a small sanctuary for art that formally resembles a home, complete with guest bedrooms. But, in fact, nobody lives there. The only thing that lives here is art. And the people who come here to enjoy it. Obayashi built Yu-un solely as a home for his collection of art.

Located in a quiet, residential neighbourhood of Tokyo, the building was designed by Japanese architect Tadao Ando. One could say that he simultaneously created both a poem and the book in which it is published. Similarly to the relationship between a book's cover and pages, Yu-un's façade consists of a glass cube containing a concrete cube inside of it. There is a distance between the two, just like we separate our inner lives from our outer lives, the surrounding environment and the layers put upon us by others. The hallway serves as a sort of meditative path as well as a purely functional means of getting from one room to the next, as do the stairs. Geometrically, the house is built in an N-form, thereby separating the supposed living space from the gallery. At the centre of the N is a triangular courtyard open to the elements, which lets the building be perceived both as a closed and open space and conjures a feeling of being a laboratory of infinite emotion.

Yu-un. Photo: Ainārs Ērglis

One must cross the courtyard in order to access the other wing of the house, and this action literally brings nature into the house – rain if it's raining, wind if it's windy, snow if it's snowing or the swelter of summer if it's hot. Ando is both a monk and poet of architecture; he skilfully manipulates not only with concrete, steel and glass but also with shadows, textures and reflections. He paints with architecture. In addition, his works of art are in constant flux depending on the time of day and angle of light.

In interviews Ando does not hide the fact that Obayashi's specifications and the creation of this project together with artists was no easy task. But, seeing as he had already “climbed aboard”, he ended up steering the project. “An architect and artists collaborating to create a unique space for art – it sounds like a wonderful idea but is by no means easy to do in reality,” wrote Ando in the project's catalogue.

Some of the artwork at Yu-un was created especially for the space, including the courtyard installation by Danish artist Olafur Eliasson, which is also one of the house's central elements. The installation consists of more than 6500 platinum-glazed ceramic tiles covering the courtyard's walls in a seemingly haphazard pattern. It was an almost impossible mission, laughs Obayashi. “Eliasson demanded that the rhythm should look as if the tiles were laid out randomly. But, as you can imagine, the Japanese are not very good at random things. So then he suggested the workers consult with Japanese gardeners, who might be able to draw diagram-like instructions. We visited with some gardeners, but they said they'd never done anything like that before and couldn't do it, either. In the end, we decided to solve this problem with the help of a computer.”

The artwork of Olafur Eliasson in the courtyard of Yu-un House. Photo: Ainārs Ērglis

Eliasson is a magician of light and a virtuoso of manipulating the viewer's emotions, thoughts and perception. He's done it masterfully here as well – depending on the time of day and angle of light, the tiles seem to be dressed in different kinds of “clothing”. Their reflections enter the house, too, through the large glass windows. In addition, as you move around, the tiles seem to sparkle like the scales on a fish, manipulating and knocking down your sense of space. At one moment, it even seems as if the tiles pull you in and make you a part of the artwork. British artist Marc Quinn's bronze sculpture, inspired by “exploded popcorn”, is in the centre of the courtyard. Quinn first photographed a piece of popcorn and then enlarged it immensely.

Even though Yu-un is a small building, Ando was able to create surprising volume and sometimes even a feeling of an unsolvable labyrinth. In one of the bedrooms, a pair of bronze lace-up boots – a sculpture by French artist Tatiana Trouvé – lies at the foot of the bed, as if thrown on the ground in a hurry. And just outside the window, on the small terrace, is one of Korean artist Lee Ufan's legendary rocks.

There is a work by Murakami on the living room wall. Obayashi laughs and says it is “very different from the Murakami we know today. It's 1998. He wasn't famous yet. Back then, he sold works like this for 500 dollars.”

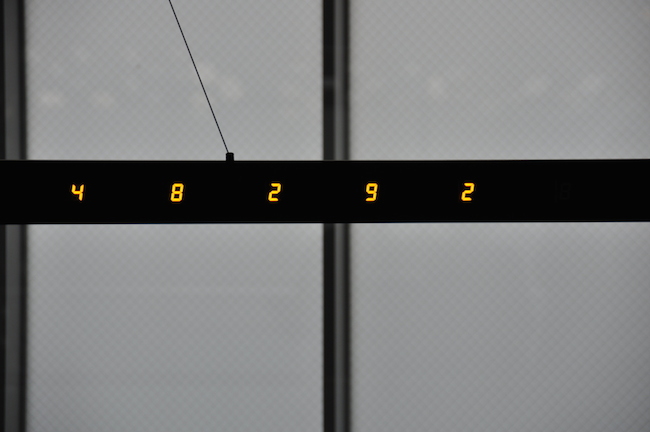

Tatsuo Miyajima. Photo: Ainārs Ērglis

Above the wooden table, which was also designed by Ando, is an installation by Japanese sculptor Tatsuo Miyajima – a row of numbers in constant motion. “Each number changes at its own speed. They embody the speed of life. Every year, each of us grows one year older. But the speed at which we feel our life is different for everybody. Miyajima's installation is about absolute and real time. Numbers are characteristic of his artwork, but he never uses the digit 0, because that signifies death.”

Yu-un's symbolic heart is the traditional Japanese tea room. When asked whether he ever uses the room himself, Obayashi answers: “Yes. I've studied the ceremony for twenty years. But unfortunately my teacher passed away last week.”

Obayashi exudes an inner strength and certainty combined with the somewhat elusive ethereal quality of the aesthete. This becomes apparent in his gestures, his gaze and how he looks at the artwork as he tells about it. He speaks simply and openly but also keeps an unmistakable distance. Obayashi is the chairman of one of Japan's largest construction companies, Obayashi Corporation, which was founded in 1892 by his great-great-grandfather. But Obayashi is the first true art collector in the family.

Obayashi estimates that he currently has just over 500 units in his collection, but only a small fraction of them can be seen at Yu-un. “40% of my collection is international artists, 60% is Japanese artists,” he says. The exhibition in Yu-un's basement level is changed three or four times a year. “I listen to other people's advice, but I'm the curator of my own exhibitions.” That is, except when it comes to physically installing the exhibitions; then he arranges for helpers.

Each year, Obayashi asks at least one artist to create a piece of artwork specifically for this space. In addition to Eliasson, Gabriel Orozco, Lee Ufan, Tokujin Yoshioka, Lee Bul and others have taken up the offer. “Unfortunately, I'm slowly starting to run out of room,” laughs Obayashi.

The name of the guesthouse/gallery consists of two Japanese symbols: “yu” means to enjoy or dream, while “un” means a house, sanctuary, refuge. “This is a place where people meet through art. Here, they converse, exchange ideas and establish new friendships.” Yu-un is not open to the public, nor does it have any employees. Obayashi always personally shows his collection to his guests.

In telling about his collection, Obayashi admits that it's always very important for him to meet the artists, and this is why he's interested in contemporary art. “I collect art by living artists. Of course, some of them have passed away over the years. That's life.” Part of our conversation takes place as we move through Yu-un, the mood of each room being replaced by the next. A few drops of rain fall on Eliasson's tiles and leave traces on Ando's concrete floors, and we take in the view of densely inhabited Tokyo from the house's rooftop terrace.

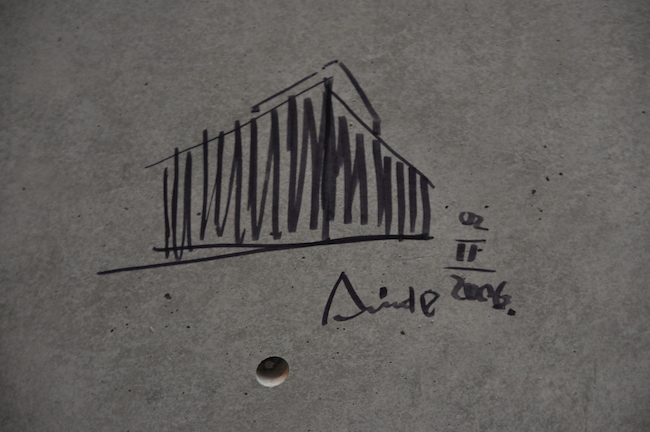

Drawing by Tadao Ando. Photo: Ainārs Ērglis

Why did you choose Ando as the architect of your guesthouse/gallery?

Actually, he chose me. One time when we met, I told him about my dream project. Back then, I was thinking of possibly inviting Herzog & de Meuron or Peter Zumthor. But, having listened to my story, Ando said, “Takeo, I can do it for you.” And I couldn't refuse him. I've known Ando for a very long time. He's already a family friend of ours. And so it seemed right that he would realise my dream project.

How did you come up with this idea of combining a guesthouse with a gallery?

I had 30 conditions regarding how I wanted this space to be. And I told them all to Ando. He took about half of them into consideration and totally ignored the rest. I told him I don't need an ordinary, functional building but, rather, more of an artistic building. We agreed with each other in that sense.

Do you remember with which work of art you began your collection?

In the beginning, I collected architectural drawings. Not just Ando. Drawings by a variety of architects. I'm in the engineering-construction business, so I've gotten to work with quite a few international architects as well. Such as Norman Foster, who kindly gave me his drawings of the building we were constructing at that time. And then I had to ask myself whether this was a gift to me or my company? To whom do these drawings belong? Sometimes that's a difficult decision. In the late 1990s I was involved with an art project for our new office in Tokyo. We asked 18 artists to create commissioned work for each of the office's spaces – conference rooms, lobbies, stairways, etc. And that's when I realised that working with artists is very interesting and a fantastic experience. I learned very much from them. And so, having been influenced by this experience, I began going to art exhibitions. For example, I went to Kusama's exhibition and met with her. The gallery kept sending me invitations, and I kept going to more exhibitions. I met more and more artists, gradually gained more experience, and then I slowly moved from collecting architectural drawings to contemporary art. I joined MoMA's International Council of collectors, where, naturally, everyone asked me what I collected. And then I began to think that maybe it was my responsibility to show these people the work of Japanese contemporary artists. I must say, they didn't know much about Japan's contemporary art scene.

Lee Bul. Photo: Ainārs Ērglis

It's paradoxical in a way. Kusama and Murakami are already global brands, but there is relatively little information about what's going on in the rest of Japan's contemporary art scene. Why is that?

That's the way it is. I think there are very many excellent Japanese artists who are simply not known abroad. And that's not just the case with Japan; the situation is similar in other Asian countries, too. Even, say, in Korea. I think it's up to the art community in general, not just the artists. There have to be good galleries, good museums and good collectors. Unfortunately, Japanese museums don't particularly collect or exhibit work by Japanese contemporary artists. Also, the number of people in Japan who are interested in contemporary art and can afford to buy it is very limited, compared with, for example, America or Europe. Maybe it's also due to the education and tax systems. We need to develop a space for art so that great curators, collectors and museum people can evolve. Luckily – and this is a good trend – more and more young people are becoming interested in contemporary art. If, for example, the Mori Art Musuem organises an exhibition of a big contemporary artist, lots of people will come. The older Japanese generation, on the other hand, loves Impressionism.

Because that's long been a sound, stable value?

Yes, it's already established art. But young people aren't afraid to take a risk. I think only about 10-20% of the artists represented in my collection will stand the test of time over the next one hundred years. Definitely Murakami; his name will be in books. Maybe Kusama, maybe Kishimoto. But I don't buy art as an investment. And I probably won't live a hundred years. So, I'm not at all concerned about the value of my collection a hundred years from now. And that's also why I don't work with curators or other advisors – I buy what I like.

At the same time, it seems that China has a very active art market.

That's in the name of business, not culture. It's a bubble. And it's going to burst, sooner or later. China's government is planning to build almost a hundred museums in the next five years. They need to buy art. And because the quantity of old, traditional Chinese art is limited, they have to resort to buying contemporary art. For them, art is an investment project. I think there are only a few really great artists in China. Most definitely Ai Weiwei. But he's been politically punished and cannot leave China. I've also got Ai Weiwei in my collection and a couple of other Chinese artists. But very little. I've found much more unique and interesting artists in Korea, Singapore and even Vietnam and the Philippines.

Lee Ufan. Photo: Ainārs Ērglis

How important is the concept of a work of art to you?

Undeniably, the concept needs to be unique, but I don't pay attention to the details of it. I think collectors mainly enjoy the opportunity to listen to concepts. The very act of listening. For example, do you know why Hiroshi Sugimoto photographs horizons? The title of a photograph might be, for example, Caribbean Sea, 1998. But Sugimoto says the title doesn't mean anything; it doesn't really matter which sea or ocean it is. It could just as well be an ocean horizon from a hundred million years ago. Because the horizon is the only thing that has not changed over the course of time. The shape of everything else – of humans, of the natural environment – has changed. Sugimoto says that his photographs are actually of that ancient ocean, something outside of time.

I once had of photograph of his on the wall titled Villa Savoye. Le Corbusier (1998). It's a little fuzzy. Sugimoto purposefully didn't focus the camera in order to create this diffuse image. He said that he thereby tried to show the original idea of the architecture, the idea that was in the architect's head. In his brain. You cannot see it, but with this fuzzy image he supposedly shows us the first time that the idea of this building materialised in the architect's mind. This photograph is supposedly outside of time. Le Corbusier is long dead. But Sugimoto shows us something that is usually invisible to people.

Many people don't know this story. But I do. And to me that seems the greatest thing about collecting contemporary art – the opportunity to meet the artists and listen to their concepts from the original source. Picasso is superb, so are Monet and Brâncuși. Maybe I can buy something by Brâncuși. But there are a lot of collectors in Europe or America who have much more of his artwork than I would. And, all of these artists are already dead; I cannot listen to them tell about their artwork. That's why I buy modern artists. And they're happy about it, too. And then I feel as if I've supported them in some way. As I said, of course, I don't know what the value of all my artwork will be in a hundred years. Maybe my grandchildren will say that their grandfather collected very strange things. But that's OK.

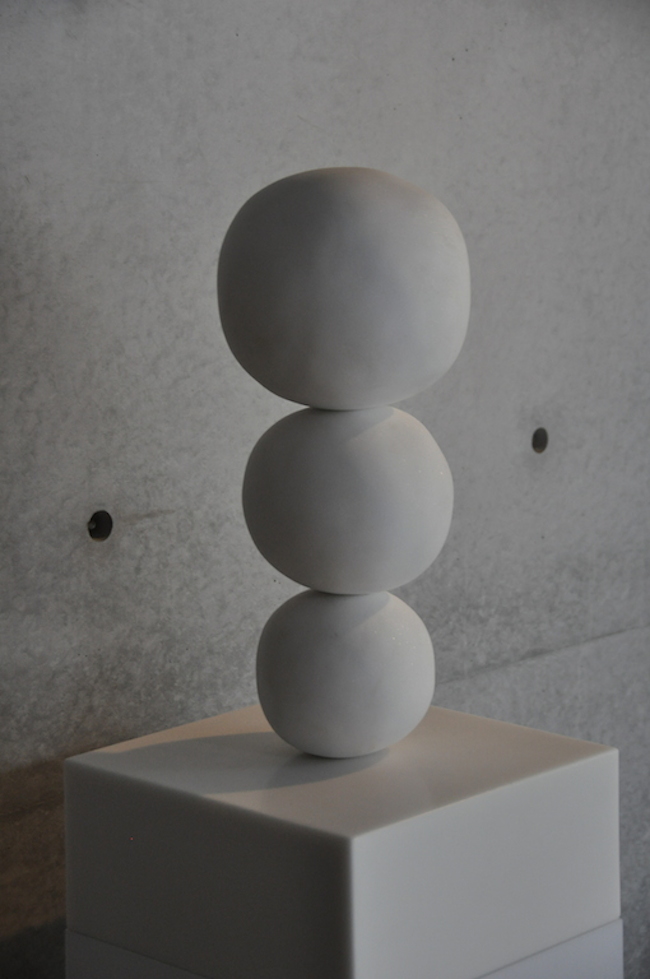

Gary Hume. Suicide Snowman. Photo: Ainārs Ērglis

Is art the greatest luxury of all time?

Yes. Maybe. I always suggest to young people – if they're at all interested in art – to try to buy some artwork, even if it's just one small piece. Not just look at art in museums, but buy one painting, for example. If they can't afford a painting, then it could just as well be a lithography, a print, a photograph. And if those are still too expensive, they can always buy a poster. Or at least a book. I try to pull them in.... To take them to an artist's studio or organise a meeting with an artist here. I've come to realise that lots of people really do try to look and see. Especially contemporary art. But they don't know how approach it and get closer to it.

Can art change people? Has art changed you?

I don't think collecting art is really a hobby. Some people like football, tennis or books. Some people collect, others don't. That doesn't mean anything. Regarding myself, I can expand my circle of relationships with other people through art. I meet with collectors from other countries, with artists from around the world, with architects and designers. Art is an international language. If you get injured or become too old, you have to stop playing tennis, for example. But you'll still be able to enjoy looking at art or collecting it. You can do that as long as you're still alive and as long as you continue to have enough money.

What do you think about art collectors who collect art as an investment?

I have no opinion. I don't collect in that way. Besides, if I collected art as an investment, then I'd constantly be regretting something.

Have you sold anything from your collection?

Maybe a few works of art. But to be honest, I couldn't sell much of it even if I wanted to do so. There's just no market for it. Especially for young artists.

Is an artist's name important to you?

Yes and no. I think balance is very important. As I already said, I have both Japanese and international artists in my collection. And there are some very well known names among them, too. Lots of people arrive here to see my collection, and so I have to show them something nice as well (laughs). But at the same time, being Japanese myself, I also show them some completely unknown, young Japanese artists. To show them that there are many very good artists in Japan. I think both sides are just as important.

Do you think any Japanese artists have become more widely known because of this?

I very much hope so. That's my main goal. Even though Tokujin Yoshioka isn't an artist – he's more of an industrial designer – I think lots of people have noticed him thanks to this building.

Is it important for you to surround yourself with art?

Yes, art is a part of my life.

Do you have art in your home as well?

I don't have any artwork in my home.

Why?

I don't know. Sometimes life without art is OK, too. One of the reasons I built this house was because my wife complained that our apartment didn't have any more plain white walls, because I had covered them all with art. And so I separated these two things. This is a space where I can enjoy my collection.

Can you name five works of art that you consider to be the best in your collection?

That's impossible. All of the works of art that have been specially created for this space are very meaningful to me, because they hold a lot of memories. And stories.

Takeo Obayashi. Photo from personal archives

What is a masterpiece?

To me? To me, it's still Giacometti. And that's why I don't buy Giacometti, because if I bought Giacometti, it would be the end of my collecting. I don't have specific masterpieces in my collection. Each work of art is a masterpiece onto itself.

What is it about Giacometti that fascinates you? There's no way you can talk to him anymore...

I don't know. I can't explain it in words. It's just Giacometti. It's very hard to tell why. Why does someone like Picasso or Monet? An explanation doesn't mean anything. You either like something or you don't.

Are you concerned about what will happen to your collection after you die?

I don't know why, but lately many people have asked me this question. I've never thought about it. I don't know, maybe I'll give the collection to someone before I die. But most of my collection is very closely linked with this building. So, the building's future is also important. In addition, I think the building itself is a work of art. I really have to think hard about this. The only thing I know for sure is that I don't want someone to destroy this house just because it's become too expensive to maintain.

This conversation took place in November, 2014.