The Mystery of Art and Its Consequences

An interview with psychotherapist and art collector Diethard Leopold, son of the collector Rudolf Leopold

29/10/2015

The Leopold Museum, which houses the art collection accumulated over the course of fifty years by the medical doctor Rudolf Leopold, is one of the most powerful attractions of the Vienna Museumsquartier. The truly beautiful building, open to the public since 2000, presents a display that features some of the most popular and iconic phenomena of past Viennese art, most significantly – works by the painters Gustav Klimt and Egon Schiele. The latter – Egon Schiele – is referenced by the Leopold family as a living artist, thus accentuating the fact that his art feels current in the 21st century, almost a hundred years after the painter’s biological death. It is thanks to Rudolf Leopold that Schiele returned from a state of quasi-oblivion to take his rightful place in the Viennese post-war cultural scene as one of its most prominent figures, recognised not only by denizens of the art world. In 2010, Rudolf Leopold, who had been appointed to the post of the director for life, passed away. April 2011 saw the new-founded Egon Schiele Documentation Centre opened with the support of the Austrian Federal Ministry for Education, Arts and Culture; the core of the centre is formed by the collector’s impressively extensive archive that contains, among other things, documents hand-written by Schiele, the records of his art and life, texts on Schiele and his creative career, etc. Leopold’s collection also features manuscripts of the painter’s poems, written between 1910 and 1912 – vivid examples of expressionist poetry.

Rudolf Leopold’s place in the museum board was taken over by his son Diethard Leopold. Meanwhile, the post of director was recently taken by Hans-Peter Wipplinger; it seems that the Leopold family is expecting great things from him regarding the future of the museum.

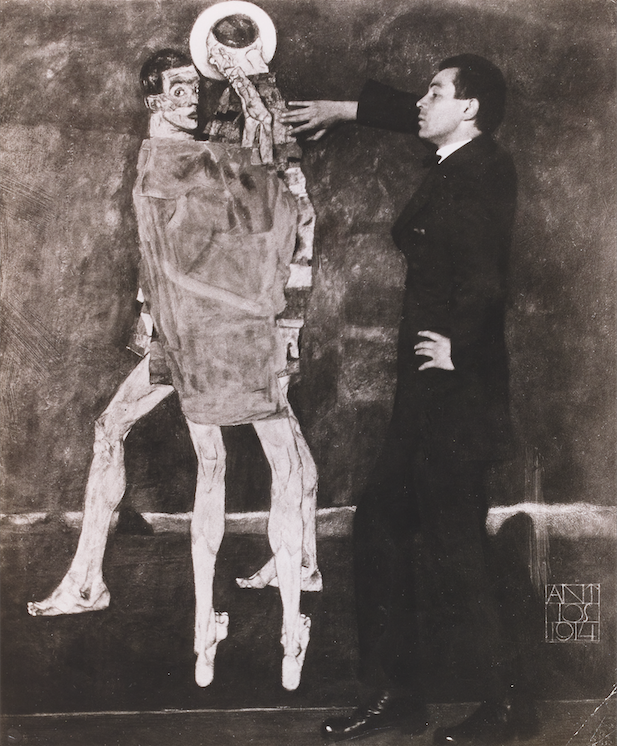

Egon Schiele next to his 1913 painting Encounter, which is now lost, 1914. Photography on paper | 29 × 23,5 cm. Leopold, Private Collection

Just like his father, Diethard Leopold’s main profession is connected with healing people. Leopold Junior is a psychotherapist; admittedly, he will confess at some point in our conversation that he has no time for his psychotherapist’s practice these days due to becoming ‘crazy more and more’ – obsessed with mounting art exhibitions. One of the floors of the Leopold Museum is currently occupied by his brainchild – the permanent exhibition ‘Vienna 1900’. It is a multimedia phenomenon that tells the story of the turn of the 20th century Vienna in a flavourful, emotional yet abundantly informative manner. Immersed in a world of nostalgia for things and times past, the visitors are confronted from a variety of angles with the view behind the huge windows that open to the Vienna of today and a vibrant contemporary life.

Our conversation with Diethard Leopold takes place in a rainy and grey day in Vienna. I am waiting for him in the vast lobby of the museum, contemplating the large photographic portraits of Schiele and watching people pass through the glass door almost like a row of ants marching down a path. When Diethard Leopold rushes, fleeing from the rain, he also seems somewhat taken aback by the number of museum-goers – at least his comment is: ‘Yes, we do have a lot of visitors on rainy days like this…’

You have been surrounded by art from the moment of your birth. What is it like to grow up in an art collector’s family?

(Laughs heartily) Growing up in the family of an art collector, especially in the family of a very passionate art collector like my father... on the one hand, it's like magic. Because as a child you don't understand the significance of the objects but you experience that the whole life of the family is influenced or dictated by the objects. And the moods of your parents change if an object is delivered or taken away. So there is a magic relationship between art and humans. And so to grow up in a collector's house is to learn that the relationship with art can be essential to life.

On another level, it's both: enhancing, wonderful and making you happy – but also threatening and taking life away from personal relationships to a mysterious level which we don't understand.

Which was the work of art that first revealed the magic of art to you?

I would like to tell you about two art objects. One is ‘The Poet’, a painting by Schiele. I was always impressed, first of all, by the posture of the body. He leans his head as if he is day-dreaming. He has very sensitive hands. Like antennae. So I felt he was drawing to himself messages from unknowable, unseen mysterious worlds. And the whole painting vibrates with this subtle energy. Actually my view of this painting today is just the same.

And I think if a child can experience a work of art, the child is right usually. More than a grownup who knows too much.

The other was a painting by the first Austrian expressionist Richard Gerstl. A painting which, as I learnt decades later, he painted three weeks before killing himself. I was always afraid to pass this painting and avoided to look into his eyes. I think I was right, too.

Egon Schiele. Self-Portrait with Chinese Lantern Plant, 1912. Oil, opaque color on wood | 32,2 × 39,8 cm, Leopold Museum, Vienna, Inv. 454

And today? Do you still find them as impressive?

Yes. Of course, I have many more favourites now, but these two are my most favourite paintings of the collection which is now on view in the museum.

Do you look at a work of art as a professional psychologist or as an ordinary viewer?

I think the mistake usually made when experiencing art is to think of art as an object. Here is the subject who looks at art or listens to art and here is the object. But I think the essential meaning of art is that there is no object. Just a united space. And in this united space there are energies going from the viewer to the art and from the art to the viewer. So the mistake in the traditional sense is to have a beautiful object on the wall. And the mistake in the present day in the curatorial art world is thinking that an art object should have a concept and you have to understand it. Maybe this is an unimportant aspect, but I think it's a wrong game. It moves the art away from you and contracts an object. Of course art is an object. But only on a secondary level.

And yet concept is an integral part of the current art scene. Do you like contemporary art?

I like the art of today. I can even appreciate the so-called ‘curator’s art’, so to speak – but only if the artist is capable of going further than the intellectual concept. Art is like the analogue clocks which all have an element that excludes the possibility of them working in complete silence, without a sound. It is the same with art. There just has to be an element that defies intellectual analysis. If an artist is capable of achieving that, I definitely think very highly of contemporary art. Because it is so much freer than traditional art. Today, you can do anything.

This summer, the Leopold Museum hosted Tracey Emin’s exhibition ‘Where I Want to Go’, which, alongside 80 pieces by Emin, featured a number of Schiele’s drawings selected by her. Why and how was the idea of this exhibition born?

I think that contemporary art shows will become a common practice at this museum. Particularly now that the post of director is held by Hans-Peter Wipplinger. But speaking of this particular exhibition, the important thing is that my family still considers Schiele a living artist. Because the artists who are biologically dead can be divided into two groups – those who only merit a strictly academic interest today and those who are still alive. For instance, Goya is alive. And I can name a number of other artists like him. And we want to spread this conviction that Schiele is alive. One of the ways to do it is by confronting Schiele with phenomena of contemporary art, promoting a dialogue between these two phenomena. And I think that we achieved that in a very convincing way with the Tracey Emin show. Schiele’s drawings could be viewed as only recently created.

You are currently not only a psychotherapist but also an art curator. In what way do these two professions communicate between themselves?

For the moment I have no time to follow my psychotherapy. I go crazy more and more. There was a moment in the life of this museum when I thought one particular topic is missing which the museum could present very nicely. And this is Vienna 1900: Klimt, Kokoshka, Gerstl. Also furniture, also design. Like Kolo Moser and architects like Josef Hoffmann and Otto Wagner. Because the collection is not just paintings. It's also furniture and design objects. But it wasn't a permanent exhibition at that time. And the museum gave me the opportunity to use a whole floor to present a picture, an image of an era. And as a psychologist I found, and to this day find it very interesting to work on a line between sensuality and information. How much text do you present and which texts do you present - or do you present music...Can the painting still survive all the other influences...An adventure of different media to produce a path where the imagination of the visitor is guided on the one hand yet set free on the other hand, so he can choose what his interests are.

Seated Male Nude (Self-Portrait), 1910. Oil, opaque color on canvas | 152,5 × 150 cm. Leopold Museum, Vienna, Inv. 465

Which of the exhibits at ‘Vienna 1900’ is particularly important to you personally?

You know... Strangely, I think for me personally the Japanese screen exhibited at the beginning of the exhibition. It's a bit kitsch, but it shows a lot of the influence that Japanese art had on the Secessionists. Maybe not this particular screen but screens in general. This is the most important object for me personally. It doesn't belong to the museum, it just belongs to me. And I have a kind of love for this kind of aesthetic.

‘Vienna 1900’ is the story of a Vienna that is no longer there. The huge windows of the museum open to a view of a contemporary city. How would you describe its arts’ life?

Since the 1980s, Vienna has developed in a way which was not imagined ever when I was a child and later in the 1960s and 1970s. Vienna still was very traditional and grey then. And oppressive in the cultural sense. But it has really opened up. I think the difficulty of Vienna is that the economic base is not so strong as in London, for example. On the other hand, in this situation people have to be creative. Of course you can't find the sensational big art like the one in some of the New York galleries. But if you have a taste for art of a smaller scope, for intimate art or for young art, which is not a well-known and highly priced art but an art where essential creative life flows, then you can find a lot that in the Viennese galleries now. Vienna is a good place for that.

Don’t you think that money and market have too much power in the contemporary art world?

I think that ever since the ‘Sensation’ exhibition the market has ruined art and made it sick – as well as the art collectors. That is true. Money dominates the art world, and it is dangerous. At the same time, there are so many art collectors whom we don’t know and who don’t have so much money. And they are looking for ‘smaller’ art.

But why would anyone want to spend big money on art?

Because money is a fluent thing. People don't know where to invest. This is a game for rich people. They have a common understanding that some artists are like investment tools. And also, you know: pride, selfishness... A wish to annoy. For example, Jeff Koons is nothing in a spiritual sense, but he is a good investment. But nothing more. That’s what I think.

Do you also collect art?

Yes. I try to round up the collection which we inherited. We now go for some important post-1945 Austrian artists. And I also collect a few very young artists which interest me. In a way – if there is something going on between me and the work.

You mentioned the inherited collection. It also contains some works of art that created quite a controversy when the heirs of Jewish families recognised values that used to belong to their ancestors. Your father Rudolf Leopold refused to negotiate, saying that he had obtained these artworks in a legitimate way. You still decided to try to reach an agreement…

Austria and the individuals living there have had a long learning curve. I believe that in cases where an object of art has found its way after the Second World War in a legitimate way – if there is no information that the work has been stolen or obtained in any other illegitimate way – then the Jewish families and the current owners should sit down at the negotiating table and work on an agreement. It could be a material compensation; it could be a division of proceeds from an auction. It could be an agreement on the value, in which case one of the sides would pay 50 % to the other. There are many different ways of reaching an agreement if both sides really are prepared to negotiate.

Egon Schiele. The Hermits, 1912. Oil on canvas | 181 × 181 cm. Leopold Museum, Vienna, Inv. 466

Your family owns the biggest collection of Austrian art in the world. Is it still possible today to speak of national art?

I refuse. I never say Austrian art. I say: art which happened to be created in Austria. If you look at Schiele and Klimt, they were internationally limited. The same with Gerstl. Even then it does not mean anything if you say – Austrian art. But some of these paintings or sculptures have become icons of the national consciousness. That is part of the history of the artworks. On the other hand, if you collect, you must make a definition. You need a concept and focus, boundaries, etc. My father made a decision very early on that he would like to present this art which happened to be created in Vienna and in Austria approximately between 1890 and 1920.

Why was he so passionate about Schiele’s art in particular?

When he started to collect, he was rather poor because he was a student. He started to collect Austrian art of the 19th century - because he loved nature, and the Austrian kind of impressionism was very about that. Then suddenly he stumbled upon some works by Schiele. And he thought – on the one hand, the composition and colouring is like the old masters’, but the topics are new and fresh and, as he felt, contemporary. Although some 30 or 40 years separated him from Schiele. Schiele addressed him in a very personal way. As a psychoanalyst, I can go further than that. Perhaps the attention that Schiele paid to sexuality, to the body, was in a way a mirror for my father’s psyche. He felt a need for something like that.

Could you describe the personality of an art collector from point of view of a psychoanalyst? What is it that makes one start and keeps from completing a collection?

This involves two questions for me. When he becomes... In the beginning, I think, it is the construction of a second body. A body which is secure and which is beautiful and interesting. And the collector is at his most happy when he is with his collection. Like a person who likes his body is happy inside his body.

The not stopping, I think, is of course a compensation for something else. Purely from a psychological stand point (of course, there are cultural reasons for the collector). The paintings aren't really my body. It's just my psyche’s game which makes them a symbol of the body. So to maintain the illusion of this game I have to continue to collect.

The importance of a ritual – like it is for smokers?

I will tell you a story. When I lived in Japan, I was sitting alone in the traditional little house on a chilly winter evening – drinking sake, smoking cigarettes and reading Yukio Mishima. And then I ran out of cigarettes. I should have found some change, get dressed and go out into the cold to look for a cigarette machine. I decided that I did not want to do that. I put down my book and spent ten minutes smoking an imaginary cigarette. And in the process of inhaling and exhaling I sublimated everything that I wished to receive from a cigarette. That was the best cigarette of my life.

The thing with collecting is this: if you are able to imagine what you want to get out of the process of art collecting (again, purely from the point of view of a psychoanalyst) and you have made it a part of your existence, you will never stop. Because you are really you.

What is your next challenge as a curator?

To convince an influential art institution (I haven’t decided, which one) of the necessity to mount an exhibition of Indian miniatures from the 16th – 18th centuries. I find it interesting not only aesthetically but also from the aspect of a different worldview. I want to present an exhibition where people would encounter an alternative view of the world. From the perspective of today, these miniatures are like fairytales. But if we can look back and imagine the reality of the age combined with the particular style of expression, a completely different way of life is revealed.

Rudolf Leopold in front of Schiele’s painting Cardinal and Nun (Leopold Museum, Vienna, Inv. 455), 2003. Leopold Museum, Vienna

Do you often travel to India?

No, India to me is something truly horrible.

Have you visited India?

Yes. But the India of today is no longer the one that belongs to the past – just like China and Japan.

Meaning that you do love the fairytale….

I love the particular worldview represented by the miniatures.

Does beauty as a concept play a role in the contemporary art world?

I think that the meaning is still important as something has been realized in a good way. It can also include intellectual concepts and sensual experience etc. So you say: oh, it's good. It's another word for beauty. Nowadays a beautifully made object is not necessarily beautiful. Francis Bacon is actually beautiful although it's not beautiful.