Why should someone want to own something?

An interview with Israeli art collector, Haaretz publisher Amos Schocken

26/10/2016

Amos Schocken, the publisher of Haaretz – Israel's most liberal, and also oldest, daily newspaper – owns one of the strongest and most unique collections of Israeli art today. The Haaretz Art Collection began more than 20 years ago and covers the past four decades of Israeli contemporary art, from the 1970s to the present day. It includes almost all current forms of artistic expression, from painting to photography, sculpture and video art. The main focus of the Haaretz Art Collection is defined as the “here and now”; it contains artwork that serves as a critique of current socio-political themes as well as artwork that follows the art processes of its day, documents the birth of new trends and directions and also attempts to track their sources.

Haaretz building, Tel Aviv

Haaretz was established in 1919 and is published in both Hebrew and English versions (the latter is sold together with the International New York Times). The building in which the newspaper is published – a grey concrete industrial structure – is located in the up-and-coming southern part of Tel Aviv to which, in part due to its low rent prices, many artists are moving their studios and where prestigious art galleries are opening up new branches. The area has a harsh, industrial aura with no trace of Tel Aviv's legendary Bauhaus heritage. The former factories are now covered with graffiti.

In order to make at least a part of his collection available to the public, Schocken opened an art space right across from his publishing house in 2014. But he says it wasn't his idea – it was the idea of Efrat Livny, Schocken's former assistant and now the curator and art historian of his art collection. “This was an office building for the newspaper before, but since newspapers are contracting, and we had to reduce staff, this space became unused, and it was Efrat's idea to turn it into a gallery.”

Artworks displayed in Haaretz's office

Artwork is also displayed in Haaretz's current offices – the curator chooses the pieces for the public spaces, while employees may choose the artwork for their own offices. Schocken is 70 years old, tall and slender, and he communicates with an intellectually aristocratic charm and a light dose of self-irony. He says that it's always been very important for him to meet and speak with artists as well as follow their careers through the framework of the collection: “It's difficult to know, in real time, whether this approach is beneficial in terms of creating a good or important collection. Still, by building a collection, one also helps artists to go on producing work – which is perhaps the best justification of all for collecting.”

Tell me about how you began collecting art.

I think it was in 1992, when a friend of mine told me that he was trying to help an artist Maya Cohen Levy to sell her work. He asked whether I might be interested in meeting her and seeing the artwork. I went to her studio, and we talked for a very long time – about her work, about everything – and I bought five or six pieces. That was the beginning. Then I realised that it's possible to buy art. Over the next four years I ended up buying about 300 works of art. I hardly ever buy one piece. It enables me to understand the artist's project if I see a number of works. At first I stored it all in the basement of the Haaretz publishing house.

I really prefer to keep my collecting activities very low-key and very discreet. Whenever I bought anything from an artist, I said to him that there was one condition – this purchase should remain secret. Finally I realised that this doesn't work. Because the next thing that happened after I concluded a deal with an artist was that he ran to tell his friends. And so the rumour goes out. I was interviewed about the collection a couple of times, and after some years we started being asked for tours, so it became more known. But, frankly, that's not my main line of activity.

Moti Porat. Untitled, 1996. Oil on canvas, 150X225 cm

Do you think about yourself as a collector?

Yes, but, you know, I've also changed my attitude as a collector. Because in the beginning it was very important to me to own the piece. This is a negative aspect of being a collector. You have this need to own something, it's silly. Lately I've understood that it doesn't make any sense. There were occasions when I bought a piece of art at a gallery during an exhibition and then the artists Gil & Moti called me and said, “You know, Amos, another collector came into the exhibition, and the only piece he wants to buy is the one that you bought. What do you say?” I said, you know, let him take it, I'll take something else. And whenever I go to this collector's home and see the piece, I feel sorry on the one hand, but on the other hand, the artist sold two pieces, not just one.

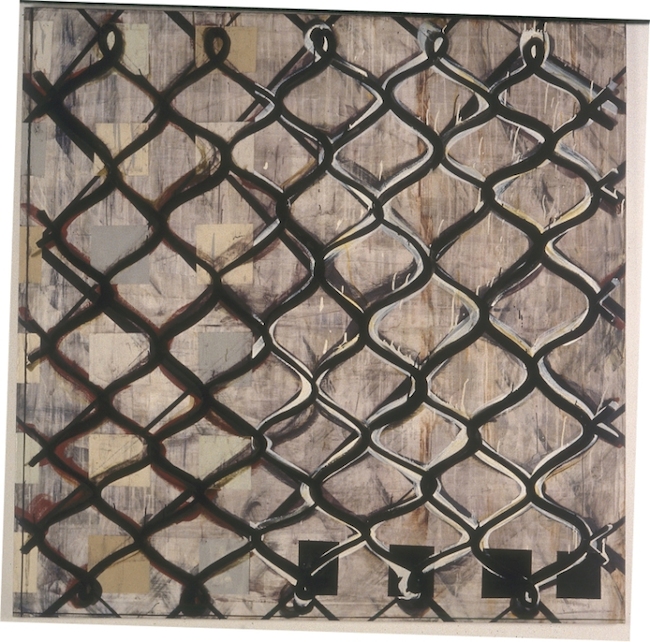

Tsibi Geva. Keffyeh, 1994. Mixed media on canvas, 184X184 cm

To be honest, that's quite a strange philosophy for a collector.

I know. So, finally you understand that you cannot own everything, and you also understand that it's better for art to be widely distributed, not stay in one person's hands. Another case was with the late Ron Pundak, who was one of the initiators of the Oslo Accords between Israel and Palestine in 1993 and also an art collector. He called me one time and said, “I'm at Tsibi Geva studio, and every year I buy a painting for my daughter's birthday. I came here with her, and the one she likes, Tsibi says, is the one you selected.” Again I said, “OK, you take it, I'll take something else.”

Which field do you think is becoming more powerful now – publishing or art?

In a country like Israel, publishing, and especially a newspaper like Haaratz, is very important, because Haaretz is such an opposition force and a powerful liberal voice that stands up for human rights, an end to the occupation and the improving of relations with our Palestinian neighbours – for all these decisively important things. The importance of collecting, I think, is just to let the industry to go on; other than that, collecting is not a very nice thing. Why should someone want to own something? My wife always said to me, “Why do you collect, only to put it all in storage? Art should be presented, it should be exhibited.” I exhibit a very small part of the collection. In more recent years, a part of my collection could be seen in the halls and offices of the Haaretz building. Right now, the building is under reconstruction, but art will return to it very soon, little by little.

Pavel Wolberg. Beit Hanoun - Gaza Strip, 2002. Color print, 44x68 cm

Why do you have this need to have art?

First of all, it's interesting. Suddenly it was interesting for me to discover this world. To see the work, to meet an artist, to talk with him about what his project is about. I don't think that I'm professional in the way some people in the art world are, but maybe my approach is more intuitive. Over the years, I think I've developed the ability to identify what is good and what is not so good, according to my own eye. Also, I'm interested in the relationship between art and society, which also has something to do with working with the newspaper. There are a lot of political elements in contemporary art, about what people are doing in Israel. We have an art that deals with political situations. The relationship between Jews and Arabs, issues between different communities... because there are differences, there are tensions. Gender issues, sexuality. All of these issues also come up in a newspaper, but they also have an expression in art. So, I find this interesting.

So, in a way, this means that your collection is another dimension of your work as a publisher.

It certainly has a presence. It's not the sole thing I'm interested in, but it has a big weight in the collection. The influence of political issues on art and how they are reflected in art. That interests me, and I can identify with that kind of art.

I also have Palestinian Israeli artists in my collection. I deliberately began collecting them about ten years ago. I don't buy international art because I don't feel that I have any special advantage regarding it. I don't have time to go to studios abroad, but that's a very important part of the collecting process – to meet the artists, to be in contact with them over the years.

As your collection got bigger, did the part of Haaretz devoted to culture also expand?

I separate the two. It was not so when we started, but by now I would say that Haaretz is the only general newspaper in Israel that covers art. We have an art critic who writes reviews of exhibitions twice a week. We also do some reports about art. And we don't write only about art; we also write about theatre, classical music, dance, cinema, etc. Our cultural section is quite big, and it's different from those of other newspapers because it deals, I would say, with what is considered more sophisticated art. Not the most popular art.

Ilan Carmi. Picnic, 2012. Lambda print, 70x90 cm

Returning to 1992, when you had bought a few works of art and realised that you were interested in art and would like to buy more. What happened next? Did it become a passion of yours?

Then I actually started to see more art. I went to galleries, I spent many, many hours in artists' studios. Efrat Livny and I began to study everything that had been bought over those years, and we created a catalogue. I began going to graduate exhibitions at art schools, and once in a while I buy things there, too. Every Saturday I go for two or three hours to the galleries and museums around Tel Aviv, to see what's going on. And not only that, I actually forced them to open on Saturdays.

On the Sabbath?

Yes. There was once a weekly newspaper in Tel Aviv, which unfortunately no longer exists, and it had an entertainment guide that included galleries and current exhibitions as well as opening times for each one. When I began being interested in all of this, only a few of them were open on Saturdays. Then I started to force everyone to be open on Saturday, because for me it was the easiest day to go and see them. The traffic on Saturday is easier, the parking is easier, and it's not a working day. So, I told the guy who made this guide to highlight in yellow those galleries which are open on Saturdays. In the beginning there were just two or three, and then little by little, and now most of the galleries are open for a few hours on Saturday. So, actually, every Saturday I do this round. I think it works well for the galleries, too, because it's free time for people.

Other collectors have probably followed your example.

Sure. When I go to galleries now, I see other people there as well.

Pavel Wolberg. Temple Mount Haram el-Sharif, 2000. Color print, 44x68 cm.jpg

But, unlike in the beginning, when you held your collection in storage, this exhibition space proves that you now have some inner need to display it publicly.

Read this and you will have an answer.

(Schocken shows me the catalogue from the first exhibition at the Haaretz Art Space. In its short introduction he writes: “When does someone who buys art become a collector? When he has a storeroom. Irith periodically asks me, 'What do you buy art for? Art needs to be displayed so that people can see it. Otherwise, who needs it.' She's right, but her wise advice isn't a cure for the collector's sickness.

“Over the last few years, the art in the storeroom has been on loan for display in museums, anonymously. It's the artist who's important, not the collector. I don't need anything more than that. But Efrat Livny thought otherwise, and the result is a space and this first exhibition devoted to the politics of the portrait. There's actually enough politics in the pages of the newspaper, but I didn't choose the exhibition's topic or direction.

“Yet when I read, admittedly with some excitement, Efrat's fascinating article in this catalogue, I found new meaning for the works of art that I knew. And so, in my case, it was worth it.”)

Is art able to change anything in the world? Can it make the world a better place?

I'm not sure. The number of people who are interested in art is rather small. Not only here in Israel, but in the world in general.

Adi Nes. Untitled (from Soldier series), 1994. Lambda print, 90x90cm

Have you sold any works of art from your collection?

I did sell some, because we had some very tough economic years at the newspaper. We had to fire people, we had to cut salaries, all this kind of stuff that you see in the newspapers all around the Western world nowadays. And I said to myself that it doesn't make sense if the collection does not participate. So, I decided to let Sotheby's sell some works.

My greatest success in this field, which lasted only two years, was that Sotheby's in New York sold for 102,000 dollars a photograph by Adi Nes that I had bought for 2000 dollars. That was great! Two years later some other collector brought that same photograph to auction and sold it for 264,000 dollars. Six years later it was sold for over 350,000 dollars.

But we don't sell a lot. True, there is another success story, although I wouldn't call it my own. I once bought three small oil paintings by a British artist at an exhibition at the Sommer Gallery in Tel Aviv. Actually, he was one of only two foreign painters that I've ever bought. I payed something like 9000 dollars for them. Then, years later, this artist was one of three candidates for the Turner Prize. He didn't win the Turner, but he was the one best liked by the public. Afterwards, representatives from Sotheby's came to me and offered to sell those works. That was flattering, of course, and I decided that, because I've never really considered the possibility of collecting foreign art because my focus is Israeli art, I would let them sell these works of art. All three paintings were sold for 88,000 pounds.

Mahmood Kaiss. Untitled, 2007. Burnt matches on wood, 59X82 cm

You do not collect art as an investment, but at the same time, there's always a certain amount of risk when you invest, as a collector, in an as-yet unknown artist. And it's probably quite gratifying to see that it has paid off.

Of course, it gives you some kind of validation of your decision. But I think there's no contribution to the world in buying an established artist for a lot of money. It's more valuable to help a young artist to create, to make a living.

One time at a benefit auction, the goal of which was to help Israeli Arab women find jobs, I bought a work by some young artist Mahmood Kaiss. The auction was organised by two former artists who had now become social activists. I bought a sculpture made of concrete with a hole in the middle. On the one side of it was a depiction of a coin from the time of the British Mandate, but around the hole was written “Palestine” in three languages – in English, Hebrew and Arabic. I liked this work of art, and I learned that it had been made by a young man from a small village in the north of Israel. He truly intrigued me, because he was obviously interested in the quality of these three languages. I looked him up, and Efrat and I went to meet him. It was about a two-hour drive from Tel Aviv. We came to his home, and we were received by his father and his uncle. We had a conversation; the uncle was the main speaker, and the artist didn't say a word.

After half an hour I said let's go to the studio and see what's in there. And so we all headed to the studio – the young man, his father and his uncle. There were a few other works from this same series, but, realising that I wouldn't get a chance to speak with this young man, I asked him for his email and asked him to send me some photos of these works of art. I later bought some of them. Later, Efrat said that this young man should definitely apply to University and seriously study art. Unfortunately, he was not accepted in the first year because, as it turned out, his Hebrew wasn't good enough. The next year, a one-year preparatory course for Arab students was established at an art school in Tel Aviv. This young man was also accepted into this course, and another year later he was accepted into the university itself and graduated with honours. By now he's already had an exhibition of his own at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art – and a great one at that!

Anat Aviv. Wanted, 1999. Oil on canvas, 42x37.5 cm each

Tell me about how the dialogue between art and the employees takes place in the halls and offices of Haaretz. Do you think art encourages people to think, to become more creative?

I've always thought that fifty precent of the people here don't even see the art that's on the walls. And the other fifty percent may see it. The reactions have been very varied. When we put up a new piece of art, some people react very strongly – they either like it or they don't like it. Sometimes they hate it. For instance, we had a piece that consisted of eight small, very beautiful portraits of young men and four portraits of flowers by Anat Aviv. We exhibited it in one of the newspaper's departments, and people liked it. Then, after a while, we added some information about the work, and the title of it was Wanted. These were portraits of Palestinian terrorists the authorities were searching for. And the next day when I came to the office, I saw all of the paintings on the floor. We have our views, but we could not expect our employees to have the same views.

Nir Hod. Peace..., 1995. Oil on canvas, 193x160 cm

Some time ago, at the entrance to our office, we had a big portrait by Nir Hod of Yigal Amir, the man who killed Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin in 1995. It did not last a long time. We got a petition from the employees that they didn't want to see this guy, to please take it down.

We exhibited a photograph by Ilan Carmi that was a staging of Édouard Manet's famous Luncheon on the Grass. As you know, there's a nude woman in the painting who is accompanied by two clothed men. The photo session had taken place in the very centre of Tel Aviv and raised a whole storm of emotions at the time. Next to the photograph we placed a small description of the work – a small copy of Manet's painting and the story of this photograph as well as the version of it that Picasso had made. Thus, some people had an easier time accepting this work of art and we did not have to remove it. All of that together also made it educational.

Yuval Atzili. Stork, 2014. Lambda print, 80x64 cm

Has a work of art ever triggered a very strong emotional reaction for you, too?

Very recently, at a university graduate exhibition, I felt a strong connection between myself and a work I saw there by Yuval Atzili. It happened very suddenly. These were genuine emotions towards a work of art. Afterwards, I met the artist and spoke with him for a very long time. He told me about how the work had originated and what he had meant with it. That really added another layer to it. But I think that emotional and intellectual excitement are not two different things. It's always a combination.