Art is essential for our quality of life

An interview with Israeli gallery owner and art collector Noemi Givon

31/10/2016

The gallery owner and art collector Noemi Givon is one of the most respected personalities on Tel Aviv's art scene. Born into a family of art collectors, her father, Shmuel Givon, began collecting art in the 1950s and created one of the significant collections of Israeli art at the time ‒ the Shmuel and Tamara Givon Collection. The museum-quality collection has three sections: the Jewish School of Paris, representing early 20th-century European modernism; early Eretz Israel Art (1920-1950), showing the local Modernism; and the new Israeli avant-garde, which originated in the 1970s. In an almanac dedicated to the collection, gallery owner Zaki Rosenfeld has thus described the significance of Shmuel Givon for Israel's art scene: “At the time (1950s, 1960s), there was no distinction between a picture shop, a framing shop and a gallery; there was no hierarchy between high and low. One plainly exhibited art, not high art. These classifications in Israeli art were set forth in the 1970s and 1980s, and one of the first to categorise them was Shmuel Givon.” Even though Shmuel opened his own art gallery, his collection was always kept separate and considered an entity in its own right.

Having studied law at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, Noemi Givon joined her father early in life. She opened a gallery of her own in 1980, Noemi Givon Contemporary Art, and rejoined Givon Art Gallery in 1986. Those were important formative years, and after her father’s death in 2000 she and her sister, Nurit Wolf, also took over management of the gallery. In 2012 she opened a separate, noncommercial exhibition space called the Givon Art Forum, in which artworks from her personal and her family's art collections as well as other Israeli art collections are displayed in thematic exhibitions.

Givon Art Forum. Photo: Laurent Burst

The Givon Art Forum is located in Neve Tzedek, one of the oldest and most charming neighborhoods of Tel Aviv. Its history stretches back to the late 19th century, when it became the first Jewish district outside the walls of crowded Jaffa. Officially, the neighborhood is said to have been founded in 1887, more than 20 years before Tel Aviv was established as a city. Neve Tzedek has experienced various periods throughout its history, including periods of neglect and abandonment, until a revival began there at the end of the 20th century. Because of its interesting and dynamic atmosphere, it has always attracted artists, writers and other creative types and still remains an oasis for them today.

The Givon Art Forum is located in a late-19th-century building that Noemi saved from destruction at the last minute. Its renovation has been one of the architectural masterpieces of the Neve Tzedek. The ground floor now contains exhibition spaces, while Givon herself lives on the upper floors. Thus, she now literally lives with and is surrounded by art.

You were born into a family of art collectors. How do you describe the essence, the foundation of your collection?

My collection emerged as a skeptical reaction to that of my parents' collection. My parents moved to Israel in the mid-1930s from Germany. They began collecting in the 1950s, when they received restitution money from Germany. They decided to collect art with this because I think that at the time they felt a very great need for culture. When the State of Israel was established, people were concentrating on consolidating the country's existence. There was an ideology, but a proper, modern culture was still developing. For example, in 1948, when Israel gained its independence, it was invited to the Venice Biennale and the government didn't even know what to do with the invitation. It invited a well-known senior Israeli artist, Yossef Zaritsky, to assemble a group that would represent Israel at the Venice Biennale. This group set off a new art movement called New Horizons, which later became known for lyrical abstraction. This group formed the basis of Israeli art from then until now and is the foundation for Israeli modernism. It is about universalism. They believed that if you make universal art, local values will creep into the art anyway. Like light, perspective, composition, etc. They painted beautiful abstract paintings and watercolors. It was the moment when the influences in Israeli art shifted from Europe, especially Ecole de Paris, to America.

The Shmuel and Tamara Givon Collection. Photo: Avi Amsalem

Then, in the early 1960s came another Israeli art movement, which was called Ten Plus, led by Raffi Lavie; they were young artists who reacted against the previous movement. They said we have to depict Israel but in a conceptual way. They organized their first exhibition at a supermarket right in the heart of Tel Aviv, on Dizengoff Square. Professor Gamzou, the director of the Tel Aviv Museum of Art at the time, was more a supporter of the Ecole de Paris, and he wasn't too pleased about the new group's activities, their audacity in organizing an exhibition at a supermarket - taking over the art crowds who were going to the supermarket instead of coming to the museum. Recognizing the group's influence, he offered them space in the museum and came up with the idea of the Autumn Salon. When the Helena Rubinstein Pavilion was built, every autumn there was a show of this group. And the group evolved and evolved, and conceptually they were very interesting, because not only were they talking about modernism, but they wanted to explore how modernism was shaping up their lives.

Most of these artists came here from Europe, and they came with cultural references and perspectives. We are all immigrants in that way, we carry a bag with geopolitical excess on our shoulder. Our parents came here with little and they made a new life. And they wanted to create a new quality of life. So they were looking to make, to find and to participate in culture.

We started from zero, from scratch. We don't have a long history of plastic arts. First of all, because of the Jewish tradition and the imperative not make the shape of a person. (The Pentateuchal Code prohibits the making of any image or likeness of man or beast - Ed.). You could not sculpt, you could not paint a human figure. So, in the beginning, in our whole visionary existence, we don't really have images that could be translated into plastic arts. This started only at the beginning of the 20th century.

At the same time, when you were at the Israel Museum, you probably noticed the Egyptian-style sculpture Nimrod. It was made by Yitzhak Danziger (1916‒1977), an Israeli sculptor, who graduated from the Slade academy and was one of the pioneers of the Canaanite movement. The Canaanite movement was a cultural-political movement that reappeared in 1939 and was quite popular in the 1940s. The Nimrod sculpture became an emblem for the group. The Canaanite movement dissociated itself from the Jewish religious tradition, instead choosing a Hebrew identity based on ancient myths. Historically, the term Canaanite refers to the Jews and non-Jews who lived here before the founding of the State of Israel. In today's culture, to identify with a Canaanite means to be a secular Israeli.

In this sculpture, which looks Egyptian, the man doesn't care if he is a Jew from this or from that part of the world. He is nonreligious, and for him the image of an Egyptian kind of god... he regards him as his own father. Because he is from here, from this area. You see it a lot in archaeology as well. Later there were also Canaanite poets, etc., and they didn't give this speech about returning to Israel, because they already belonged to it, to the Hebrews. Because they were here from older times, and this is something very interesting, which is also reflected in art. It also assures a freedom from the many boundaries, merely religions, imposed on us today in our part of the world.

Good Israeli art is aimed at the political via non-political instrumentation. It's not done in the service of the government, and even if it receives subsidies from the government, there is almost no connection between what the artist is doing in his studio and the government. I believe that an artist can do a much better political job when not on the face of it. We have just a few political artists like Yael Bartana, who represented Poland at the Venice Biennale in 2011. But she is not the classical representative of Israeli artists, because she uses criticism of Israel as a fundamental tool. I prefer when an artist, as an example, is using the idea of immigration, which is a big deal now and is not a political issue but a purely human issue. So to throw light on a human situation, that is what we do expect artists to do. Another way would be to look at reality in its very eyes and derive from that images that even the wildest of artists wouldn’t invent. For me, that is OK, too.

Good Israeli art was always about language, it was never about the publicity of wrongs or pinpointing the worst in a declarative way. And I think that artists here are very clever in not dealing directly with politics, because the politics here change day to day, hour to hour. And it's not the task of the artist to comment on that, that would make his art limited in influence and limited in endurance. It's good for this moment, but the question always is whether it's going to last for the next fifty years? Is it doing justice to our community as people? We don't need journalism in art. That's done much better by documentary cinema. We have great directors, for example, Udi Aloni. His movie Junction 48 (2016) is very important at this time.

The Shmuel and Tamara Givon Collection. Photo: Avi Amsalem

We need to concentrate on what really matters to us in art for our quality of life. It's as simple as that. Since culture was essential for our parents after the construction of Israel, it's the same for me. If we want to live here, one of the things that helps us keep our sanity is art.

Returning to your question about our collection. When my parents collected in the 1950s, they collected what people were doing then. They were collectors in real time. We don't have that many collectors in Israel. We have just four or five collectors, but there are only two collections whose agenda is Israeli art; the other collections are, let's say, 80% international and 20% Israeli art.

The way my family grew here ‒ my parents coming from Germany and constructing a kibbutz in the north of Israel, getting restitution money and starting to buy art ‒ that focused us, as a family, on collecting Israeli art and on supporting Israeli artists. We live with them. This is collecting in real time while integrating in a new place. You see an emerging young artist, you follow him, you reach a point where you are convinced and you want to collect him. And then you have other issues to deal with, like preservation, for example. You have to keep the collection somewhere, especially if you have more than 500 works of art. And this is another problem of art. In the end, most of it doesn't see the daylight. Therefore, one of the Givon Art Forum's goals is to make artwork that has long stood in a warehouse visible again. Each of the exhibitions that have taken place here has been devoted to a different theme and has featured different works of art, thereby allowing them to come out of the warehouse. I'm also willing to cooperate with other collectors to show other collections as well.

Installation view from the exhibition ‘Who is Content and Lives?’, 2015-2016. From left to right: Yudith Levin, Pieta (1982); Yudith Levin, The Bather (1982). Photo: Avi Amsalem

So, unlike the gallery, the Givon Art Forum operates as an independent, noncommercial exhibition space?

It's curated. At the moment there is a show titled ‘Who is Content and Lives?’*. Which is an enigma, and I wanted to look into this enigma about existence. It's all about fragility, about things falling apart, etc. There are more holes than wholes in these works. There are a lot of unpainted and unsaid things. Everything in this show is fragmental. It's how I feel in this period. I feel things falling apart, not keeping the wholeness that you expect to see in art. Everything is fragmented. It could be music, it could be anything. You go out in the streets and you see that everything goes, and there is no sense of wholeness. Also all these fights between religions, between politicians, etc.

This is a gigantic problem of our times. And this is all over, not only here. So, I wanted to make a show about “who is content and lives”. But nobody stood up to say that they are content and live, because it's not in the realm of the private person to solve it. If you put this fragmental art together, you can find hope in that artists are taking care of the issues not necessarily in a political way, but in an artistic way, in the artistic language. And this, I think, is essential. So, this is why I'm doing it. It turned out as a call against globalisation in art.

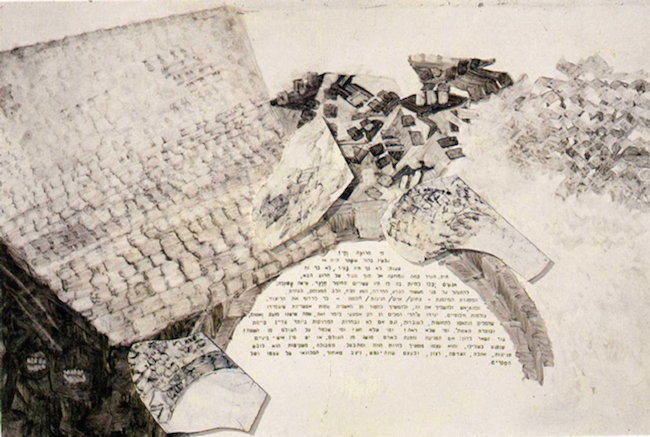

Nurit David. Who is Content and Lives?, 1984

“‘Who is Content and Lives?’ is a thematic group exhibition, whose starting point is Yudith Levin’s Pieta (1982). The exhibition’s second starting point is Nurit David’s work Who is Content and Lives? (1984). Providing the exhibition with its title, David’s Who is Content and Lives? recalls also Marcel Duchamp’s famous epitaph: ‘Besides it’s always the others who die.’ Assisted by the associations and implications of its two starting points, the exhibition ‘Who is Content and Lives?’ stems from the thought that death can only be dealt with from the point of view of life, and that entirety can only be expressed by incomplete details. In David Reeb’s broken glass painting (Untitled, 1990), the broken pieces defeat the idea of a defined whole.”

- From the exhibition text by Ory Dessau.

In my collection I'm running away from everything depictive of reality. I think my collection is more philosophical, more conceptual. It's more spiritual and more about a representation of content.

This summer, the media reported that a group of Israeli artists, museum directors and representatives from art schools had signed a petition addressed to the state ministry regarding increasing anxieties about the restriction of liberties, unfair distribution of funds and possible censorship. How serious is the situation?

Yes, there is a lawsuit. I was among this group, too, but I decided to withdraw, because it's not just a petition; it's also judicial proceedings involving cultural institutions that rely on public money. We don't depend on public money, and not only do we not depend on it, we don't want public money. It's the only way to keep our freedom. So, private people have to get out of this. But, from the viewpoint of cultural institutions, they're completely right ‒ they have a right to know where the money goes and why, and they also need autonomy when making decisions. Because the more the government would like to put their hands on art, the more political it will become. And this doesn't serve the art scene. I don't believe in artists being political. I will say it again, that the cinema does it better. So, it's a very crucial lawsuit, it's a fight for the freedom to create without intervention.

David Reeb. Untitled, 1990

Do you think art has the power to change anything nowadays?

I think not. It should not attempt to change, but it should attempt to keep its freedom, which is also in the best interests of the viewer and society at large. To keep the space of creation since it belongs to the creator. No one can take it from him or her. Not a government, not another person, no one. We are lucky in Tel Aviv that the spirit is very free here. It's a free and a cosmopolitan city, unlike Jerusalem and other parts of Israel. What you see here, how people live here ‒ this is what we must keep. This freedom of creation. And for this we are willing to fight. Me as a private person, and those who represent the public art institutions. They should keep their freedom to educate and show what they need to show. And this is the message we have to give to young artists. We are more committed to young artists than to the government. But, yes, it is true that art is an icebreaker between people and an excellent diplomatic force, not used enough between countries.

You also collaborated with the Tel Aviv Museum of Art in respect to the Shmuel Givon Prize.

Most prizes are given for achievements. My father, however, considered it his mission to attend to the next work of art an artist would make, but he wasn't able to realize this idea during his lifetime. So, when he died in 2000, my sister Nurit and I decided to do what he had wanted to do, and we did it for twelve years. We gave prizes to artists to make their next work of art. And, unlike many other prizes, they were not required to give this work of art to the museum, organize an exhibition or otherwise account for what they'd accomplished. After all, the work of art may have turned out to be unsuccessful.

How were these artists selected, and how big was the prize?

We had 90‒100 applications every year. In all, 18 artists received the prize of $5000. When we closed the prize, at the time we were working on the book. There was a professional jury with the Tel Aviv Museum that operated and presented the prize. Later we decided to support artists in other ways while following up on our father’s agenda.

Installation view from the exhibition ‘Who is Content and Lives?’, 2015-2016. From left to right: Moshe Kupferman. Untitled (1999); Micha Ullman. Glasess (1996); Micha Ullman. Untitled (1996); David Reeb. Untitled (1990); Maya Attoun. Daily Wonders (2004); Moshe Gershuni. Untitled(1978). Photo: Avi Amsalem

What do you think is the main role, the main responsibility of the collector nowadays? That is, in the market situation we are living in today, which is completely different from your father's time.

In my opinion, there are two types of collectors today. There are collectors of names, big names and big money. And there are collectors of an emerging vibrant art scene. And I prefer the latter to those of the top scale. Because top-scale collecting is too misleading. It smells of money and of consensus, and I think this does not contribute to art. For me, Damien Hirst is a mediocre artist. And so is Jeff Koons. Of course, there are some very good artists, but there are also PR-oriented artists who actually “punish the buyer”, who punish the buyer putting millions into their works of art. “Give society what it deserves” is the essence of Damien Hirst, for example.

It began in America with Keith Haring and other notable artists belonging to this so-called “pay to play” mentality. Only very few of them are really valued as highly as they are priced. They have pushed aside some of the pillars and founders of American modernism, especially those of the New York school: Robert Ryman, James Rosenquist, Frank Stella, although luckily enough he has continued successfully and reappeared in his fullest strength, thus proving his position and his indisputable status. There are many review analyses in The Guardian this year about what money has done to art whilst blue chips are getting more and more expensive. This is the process I've seen over the last ten years or more, that big money has to be spent on something or another in an era of tax revelation and low or none interest rates. So, it goes to real estate and also to art. Art became the ultimate offshore ‒ the work of art could be in one country, and the money could be in another country, and in the meantime the person lives in another country, and the buyer lives in still another country, while the work of art is to be stored in yet another country. So, above this offshore is only the moon.

In this scenario the galleries and collectors who are in the middle have suffered. It wasn't worth it to buy a piece of artwork that costs 100,000 dollars or 50,000 or 20,000. It wasn't enough money to dispose of. And, because we're not in the millions bracket, and because the 100,000-dollar works of art usually aren't in that bracket either, we were not selling as well as the ones selling for millions. So, for us, it was ‒ and still is ‒ a disappointing period. At the same time, though, we got the real art lovers, which is the bright side. That is, the art lovers, with the little that they have, they were willing to spend it with us. But I think we're slowly approaching the end of that period, and prices of works of art will stabilize according to demand for art that is connected to quality, not motored by tax-path venues and ventures.

Erez Israeli. Lowland, 2011-2012. Variable sizes. Epoxy, concrete, wire, walking sticks

But what do you think regarding the local art scene ‒ are the numbers of these art lovers growing?

The thing is that every society, not only Israel, has the bourgeoisie level. They could be professors from the university or they could be lawyers or doctors or merchants. But, considering the current art market, their capacity to acquire art has shrunk in recent years. And it is precisely these people who have always been the best buyers, not the super-rich. Israel doesn't play a big role in the international art market. I think in the next period we're going to have a bigger role on the international scene, because people will go back into art. And if you're looking for quality, we have international, universally relevant quality.

And yet, there are a number of well-known Israeli artists.

Yes, but not enough. Moshe Gershuni is one of our most visible living artists. He had a show at the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin after Udo Kittelmann came to visit Israel, saw him here and had the insight and conviction that it takes to curate a show with him. But that is not enough to make it altogether international; you need more than this, you need more museums to get in.

Now we're facing the next dOCUMENTA, and I'll be very surprised if there are more than one or two Israeli artists there. We are a little bit outside the European fence. In some way, our situation is similar to that of Greek artists. We'll always be outside the fence until the moment we will be discovered and attended to. But for this we need to have a better political atmosphere, which is true for both of our countries, even if on different stress topics.

Speaking of Greek art, Greek art collectors such as Dakis Joannou and Dimitris Daskalopoulos have done quite a lot in popularising Greek art in the world.

But it doesn't help these artists all the way. It's the same as here. In the end, you scarcely find them at MoMa or Tate Modern or the Centre Pompidou. Maybe one might sneak into the really international level. But not like the Italians. At the moment, we don't have ‒ not in Greek art and not in Israeli art ‒ an artist that can come onto the international scene like an earthquake. Like a Kutlug Ataman or Maurizio Cattelan or Louise Bourgeois, or even like Ai WeiWei.

This art positioning seems to be on the way to being mended by activities outside of the commercial art world at the biennales and other art meetings, where we already see and will see more of this branching out from the big centers as directed by some seven museums and ten collectors. That will hopefully bring the return to the art scene of more art critics with new agendas. An example of an important correction is the review of aged women nowadays [Joan Jonas at the American pavilion, last Venice Biennale - Ed.].

You actively support the enacting of droit de suite (resale royalty right) in Israeli legislation.

Yes, already 56 countries in the world have signed on to it that an artist should receive a royalty payment when his work comes out on the secondary market, but it's very difficult to pass such a law in Israel. It was also very difficult to pass in England, because auction houses were afraid that they'd sell less at auction if a buyer has to pay a royalty of approximately two percent. They did everything possible to halt this law, and it did finally pass. My sister and I, we sold an artwork by Paula Modersohn-Becker in Berlin, it was from my father's collection. And because it was sold in Berlin, we had to pay a royalty percentage. I had no problem with that. The two percent went to the family and descendants of Modersohn-Becker, and I was very proud of that. So, sooner or later we have to make this law. How is it possible that an artist who sold something for 2000 dollars back in the 1960s or 1970s, and now sees it sell for hundreds of thousands more, doesn't receive one or two percent of that sum? It's a very big injustice towards the artist and his family.

How important is it also from the standpoint of popularising a local art scene for a gallery like yours to participate in international art markets?

I did a lot of Basel, but I don't want to be an ambassador of Israel anymore. I don't want to come to an art fair and defend my country. I want to defend art, but everybody just asks me about politics. The way we work now is more towards curators, art historians, and museums. People know me, I know them, we can do exchanges. For example, recently we did two exchanges with galleries in Berlin. There is always another way. And I'm not the person to stand at an art fair booth. I think art fairs are part of the economic scheme that I explained to you before. They're there to change the geography. But I don't want to and I haven't the economic power to change the geography. I'm here, I'm strong here, I want people to come here, like you came here. I don't want to go out into the world, running after people, convincing them that we are worthy universally.

I read that, all his life, your father dealt with the inner conflict between him as a gallery owner and him as a collector. The crucial question of whether an art dealer can keep the best paintings for himself was always whether an art dealer can keep the best paintings for himself was alwayson his mind. How is it with you?

We do not see a conflict of interest. Most of the time I collected works that no one else wanted, or ones that were ahead of their time and wouldn’t sell anyway. I also have a tendency to buy “out-of-the-way” art works rather than what’s considered to be the best. My eyes, or a dealer's eyes that have seen so much for so long a time, our demands of art for ourselves may be quite different. These works, when purchased, are not to be translated into monetary value ‒ for that, we, as gallerists, might have more appropriate works to sell. So this is a nice thing about being an art dealer who collects art.

Your parents spent their life among artwork, and so do you. How it is to live with art, to wake up and fall asleep surrounded by art?

This should be found out through historical collectors of the 20th century like Gimpel, Kahnweiler, with whose passion I find affinity. In my case, this could also be associated with motherhood, having given birth to a child at age 50.

Tamar Hirschfeld. The Pianist, 2013. (Tamar Hirschfeld is the youngest artist collected by Noemi Givon)

There is a philosophical essay in the book about your family on collecting, art and olfaction, which I found very intriguing. Just one quote: “Things are not unified but need to be collected and brought together from their partial object solitude according to subterranean logic inching towards a metaphysics of repressed olfaction. A collection suggests that objects do not belong organically, but are diffused and artificially scattered.” In a way, making a collection is similar to making a perfume, its continuous search for rare ingredients and new dialogues. Do you agree?

Yes, the need to create a new wholeness, in order not to say a new world of existence, from several or even many differentiated identities and presentations ‒ at the end nothing is accidental, or occasional. It is also a question of how strong an ego the collector possesses. If it is a collection that goes into depth, or one that goes for quantity, that’s another parameter. A few weeks ago, when visiting Frieze, I posed that question at one of the talks to a collector, and from his answer I gathered that he had a ten- or fifteen-year agenda before he would sell, and his purchases were rather spontaneous, a matter of gut feeling. Well, this cannot happen with a gallerist who collects.

I think we have a good example with the Lambert Collection and previously with Anthony d’Offay. Collectors of this kind are not planning to sell their collections even in the worst circumstances. Pinault is a good example, coming from the commercial-transactional world of art into fully identifying as a collector of museum stature. I think Erika Hoffmann is a great example of a collector even though she didn’t come from art- commerce. At the end of the day, besides the pleasure effect, owning art is also a burden that needs to be managed. That's what Nimrod Reitman is writing about in the book. Merely a problem of identification.

What inspires this unstoppable drive to collect ?

We all want the same thing, which is to prolong life and constantly reset our values.

* Participating artists: Avigdor Arikha, Maya Attoun, Ido Bar-El, Pinchas Cohen Gan, Yitzhak Danziger, Nurit David, Moshe Gershuni, Tsibi Geva, Erez Israeli, Aharon Kahana, Moshe Kupferman, Raffi Lavie, Yudith Levin, Efrat Natan, Lea Nikel, Gabriel Klasmer, David Reeb, Yehezkel Streichman, Pesach Slabosky, Micha Ullman.