“Art is a huge mystery”

An interview with German gallerist and collector Aeneas Bastian

08/03/2019

Aeneas Bastian represents the second generation of art collectors in his family. Since 2016 he also directs Galerie Bastian, established in Berlin in 1989 by his parents, Heiner and Céline Bastian. The gallery focuses on leading German and American post-war artists, among them are Joseph Beuys, Anselm Kiefer, Cy Twombly, Robert Rauschenberg, Andy Warhol and David Hockney, most of whom were and still are friends of the Bastian family. As Bastian’s father has stated in numerous interviews, he has always believed the importance of personally meeting artists as it gives one a complete different way of understanding their work and its essence. Heiner Bastian was mentored by Joseph Beuys and worked as his assistant for several years, later becoming the dealer for Beuys’ work. In 1988, two years after the artist’s death, he organised an extensive retrospective in Berlin in honour of Beuys and in subsequent years also organised other exhibitions devoted to the artist’s work.

From the collection of Aeneas Bastian: Joseph Beuys »Unicorn [Einhorn]«, 1956-57, Watercolor, ink, Brown cardboard, 14,8 x 20,8 cm [H x W] © Joseph Beuys Estate Düsseldorf/ VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn/ courtesy BASTIAN Berlin

In early 2019, Galerie Bastian celebrated its 30th anniversary with the opening of a new space in London’s Mayfair district with an inaugural exhibition of Andy Warhol Polaroids. The gallery’s new home is on the first and ground floor of a former tailor’s atelier located on Davies Street. The space was designed by David Chipperfield Architects. The laconic white walls and light grey sandstone floor of the 90-square-metre space provides the perfect unobtrusive backdrop for the gallery’s central focus: art. The only sculptural, decorative element within the space is the staircase with a glass balustrade that leads from the exhibition hall down to the private showroom.

.jpg)

Installation view of ‘Andy Warhol Polaroid Pictures’ at BASTIAN, London, 2 February – 13 April 2019. Image courtesy BASTIAN, London. Photo: Luke Walker; galeriebastian.com

The inaugural exhibition, on show until April 13, presents 60 Polaroid portraits from Warhol’s Studio 54 and The Factory period. It includes photos of the artist himself as well as a legendary entourage from that era: Yves Saint-Laurent, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Paloma Picasso, Mick Jagger and many more. Near the stairs and set a little apart from the main exposition is another, smaller row of polaroids. There we see polaroids of all three Bastians: Heiner and Céline as well as seven-year-old Aeneas dressed in a black-and-white sweater with an orange and red scarf. The polaroids were shot in 1982 and demonstrates the close tie that the Bastian family had with Andy Warhol. Aeneas’ parents were introduced to the grandfather of pop art by a German publisher who had asked Heiner Bastian, working at the time as a curator and writer, to edit an upcoming publication dedicated to Warhol. The relationship naturally developed and flourished into a friendship.

But Chipperfield’s participation in the London gallery project is no less significant. His office also designed the Bastian Gallery’s home in Berlin at Am Kupfergraben. Opened in 2007, the building will be donated to the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation in a ceremony on March 12 of this year, after which it will serve as an educational centre for families and student groups visiting Museum Island right across from it. “We feel that we’ve had the privilege of working with some outstanding artists and that we should give something back to the general public, and especially facilitate access to culture and visual arts. The donation of our building is one of several crucial steps to make visual culture more accessible and to try to achieve a more democratic approach and open museums up to everyone,” says Aeneas Bastian during our conversation.

He believes that “Art is a mystery, a kind of crystal ball, if you will, that lets us take a look at the world from a different vantage point.” Art has undeniably influenced his whole life and the choices he has made. Art poses questions, but art also helps one arrive at answers.

.jpg)

Installation view of ‘Andy Warhol Polaroid Pictures’ at BASTIAN, London, 2 February – 13 April 2019. Image courtesy BASTIAN, London. Photo: Luke Walker; galeriebastian.com

I’m curious why you decided to launch BASTIAN London with an exhibition of Andy Warhol. I know he’s a part of your family history, but nowadays Warhol is everywhere, so it’s a little bit of a cliché as well.

Well, there’s definitely the personal perspective, because I had the opportunity to meet him, even though I was very young at the time – just seven years old. I was a child rather than an adult, who might have different memories. Probably that’s why I don’t think too much about the general reception and him being everywhere, or him being a global artist. I don’t think the number of exhibitions obstructs the outstanding quality of Warhol’s work. There’s probably a similar phenomenon with Picasso, who is also featured in many exhibitions around the world, but still much of his artwork is so extraordinary. So I don’t think we will really get tired of looking at Warhol’s work.

Was the meeting at Warhol’s Factory the only time you met him?

I met him several times with my parents. And they were not gallerists at the time; they were curators and writers. So, in a way, they had a different approach. They were not there to talk to him about a gallery exhibition or sales but to really speak about his artwork and his work on books and non-commercial exhibitions.

Your father was the one who introduced Warhol to Joseph Beuys when Beuys had an exhibition at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York City in 1979?

That’s true. My father was Beuys’ assistant and studio manager at the time, and he introduced him to Warhol when Beuys was at the Guggenheim Museum in New York installing his exhibition. That’s when they first met each other.

It was like a meeting of two giants of art.

Maybe it wasn’t a meeting of two giants; it was a meeting of two extraordinary personalities. And they obviously found each other very inspiring.

Céline, Heiner and Aeneas Bastian at the opening of the exhibition »Andy Warhol - Early Works« at Villa Schoeningen, Potsdam 2011. © AEDT.de/ Krempl

Tell me a little about yourself, because it’s interesting that you’re the second generation from your family to be so closely involved with art. Did you always know that your life would be connected with art, or did you also go through a “young protester” phase where you wanted to take your own path?

Of course, I had such a phase. I grew up in Berlin when Berlin was still a divided city, with the Berlin Wall running through it. Having grown up in West Berlin, I went on to study at the University of Paris, and I guess at that time I was not really much into visual art. I focused on literature. As a student, I had this idea of working for a publishing company or maybe becoming a publisher myself one day. Most of the friends I had in Paris were writers, critics or people working for publishing companies or teaching literature. So, I was going in a different direction.

Later, when I was about to complete my studies and was working on my PhD thesis, I really rediscovered art. But I can understand that phase of protest very well. You have a moment of reflection and maybe taking some distance. Even a moment of revolt, in which you think “No, I would rather do something completely different.” But when you grow up surrounded by artists, curators and collectors, you’re really immersed in all of that. I guess some people who’ve grown up within these art families, they do something different later on, but most of them do something that has to do with culture. Sometimes they go from art to music or literature. Or maybe they go on to work in design or even architecture, but they stay within that general field. I returned to art when I finished my studies.

Was there a specific point when you decided that you wanted to return? Something that brought you back?

Well, I think Paris – which is the city I spent most of my university days in – is a great place, but it’s also a city focused on history and the past. When I returned to Berlin, which is my hometown, I found such a vibrant scene of artists more or less my age who had taken studio spaces and were working there. And I found it very exciting to have a dialogue with them. I think, in a way, these younger artists really brought me back to art.

Not the artists your father collected and whom you were surrounded by during your childhood?

I was definitely influenced by all that, and I’m still continuing with Warhol, for instance. But back then I really think it was these younger emerging artists based in Berlin who brought me back to the art world.

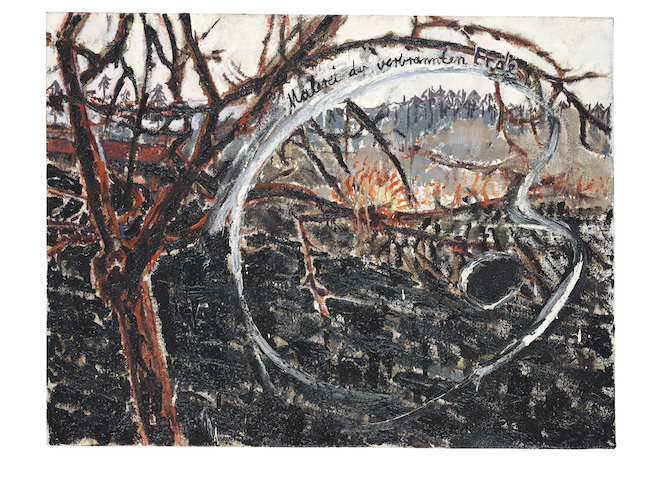

From the collection of Céline Bastian: Anselm Kiefer »Painting of the scorched earth [Malerei der verbrannten Erde]«, 1974, Oil on canvas, 95.3 x 125.5 cm / 37.5 x 49.2 in. [H x W] © Anselm Kiefer, courtesy BASTIAN Berlin

I’m sure you’ve discussed art with your father many, many times. What is it that you look for in art, and what makes your approach different from what your father has always looked for in art? As far as I know, he owns one of the largest collections of Anselm Kiefer’s work. So there’s definitely something he looks for in Kiefer’s work, a reason why it’s so close to him, no?

Not only Kiefer, but I would also add Joseph Beuys and the German post-war artists. Well, I think there is a difference. Biography, first of all – my father’s life. And I do think his first steps in the art world began with the somehow traumatic experience of the Berlin Wall. Also, I feel that the issue of guilt and responsibility played a part, especially the responsibility of the Germans for such an indescribable disaster – almost the end of the world, in my mind – and this mass destruction and the killing of millions of innocent people and the horror of war. I think he was really searching for an explanation, or maybe the response that he felt artists could give. And maybe searching to find a way from that terrible past to the future. I think it was quite natural for him to focus on German artists of his generation, artists who themselves were searching for an explanation and were thinking about those things. The end of the war in 1945 was, in a way, like a point zero, a point from which to start over again from nothing. But, of course, you have to realise the enormous responsibility, because Germany started this horrible war and caused the disaster, so to say.

Do you think he found his answers in art?

Well, I guess that with his very close friendship with Beuys and Kiefer he had a dialogue that he found very inspiring. And I think the work of both Beuys and Kiefer is deeply rooted in the exploration of German history. So I assume my father found some answers to his questions in their work. And his many meetings and encounters with them led to real friendship.

My approach is different, because I think my turning point, or experience of German history, is really when the wall came down, when the division of Germany was overcome. And that, of course, also left many questions. So, I think it’s quite natural that I have a bit of a different approach.

What is your approach?

It’s hard to define. (Laughs)

A few years ago Egidio Marzona, whom I’m sure you know quite well, said to me in a conversation that art is still a question mark for him.

Oh, I completely agree. I think all the definitions and explanations that people come up with are not very satisfactory. Art is a huge mystery and such a tremendous source of inspiration. Maybe that sounds like a bit of a cliché, but I really feel that outstanding artwork just leaves you to deal with the mystery, the riddle it represents. It never comes with prefabricated interpretations; you just have to read it all over again and try to understand it. I find these mysterious works of art particularly captivating; I like the challenge, but there are no easy answers.

From the Bastian family collection: A marble head of Athena Parthenos, late 1st-early 2nd century A.D., marble, Height: 39 cm / 15.4 in. © Jörg von Bruchhausen, Berlin/ courtesy BASTIAN Berlin

Returning to your family collection, how do you see your role in continuing it? Do you plan to add something to it, or will you maybe choose your own, separate path? In a way, a collection is a living organism, isn’t it?

That’s true. Well, we have an important collection of Beuys’ drawings, probably the largest collection of his drawings held in private hands, so I’m continuing that and sometimes I add work to that. I’m also continuing the collection of 19th-century photographs that my parents started. It’s really the early days of photography, the first generation after the prototypes, the pioneers, the inventors of photography. It’s also a generation of explorers, travellers and adventurers. They travelled across the Mediterranean and they went to the Middle East and they just took pictures. My parents and I are all very interested in the birth of photography and the creation of photography as a new medium. So, that’s something we collect, too.

I also collect antiquities: Greek, Roman, stone fragments, marble fragments. I like doing something that’s not related to the gallery and its exhibition programme. But that’s part of a whole different world, something that sort of goes back to the world of mystery and gods and mythological tales. So, something completely different. Regarding the collection, what it mainly contains is German art and early photography, but then I’ve also begun putting together this group of Greek and Roman pieces.

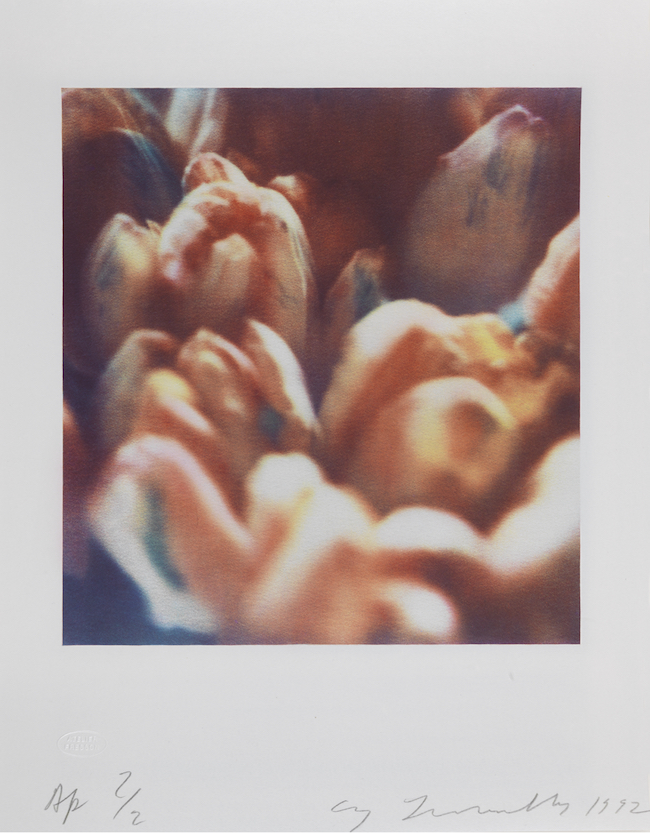

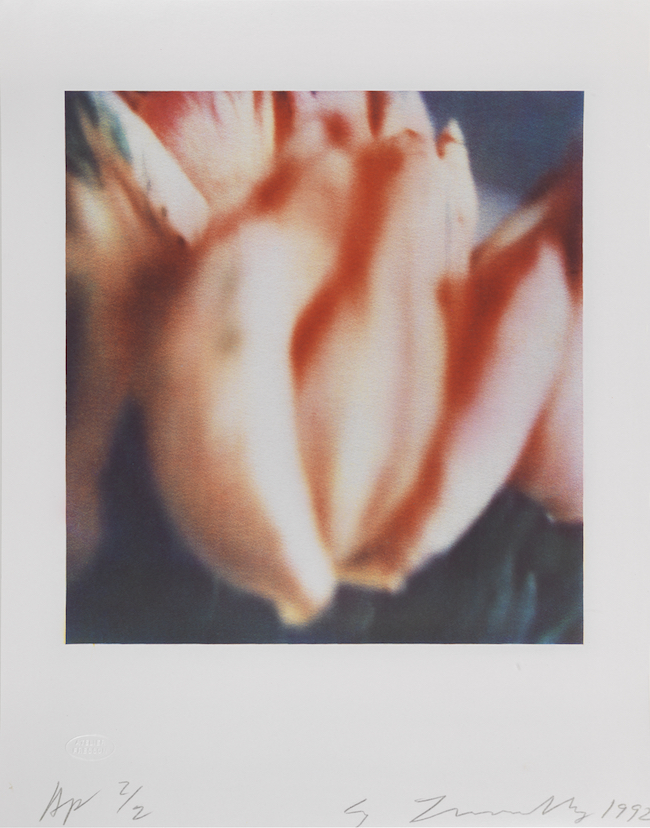

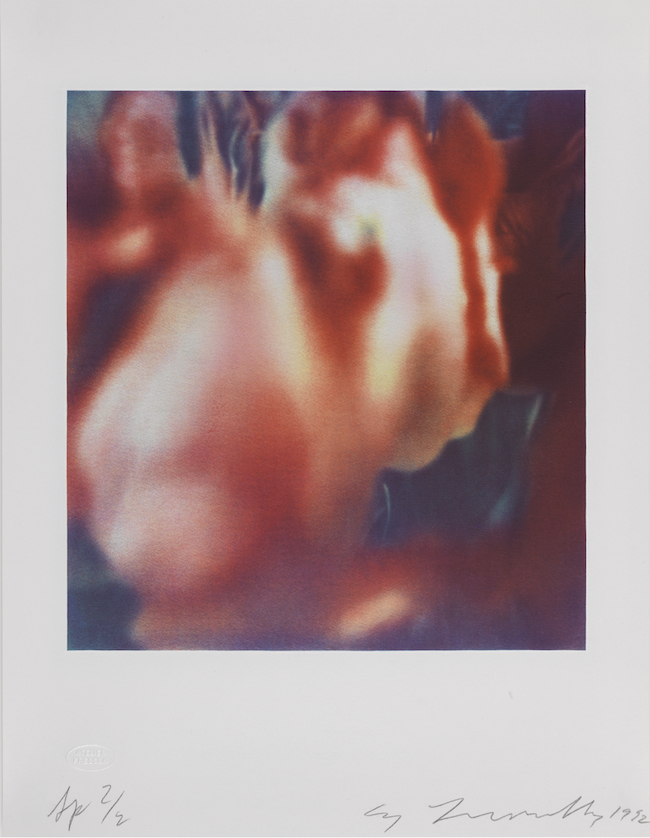

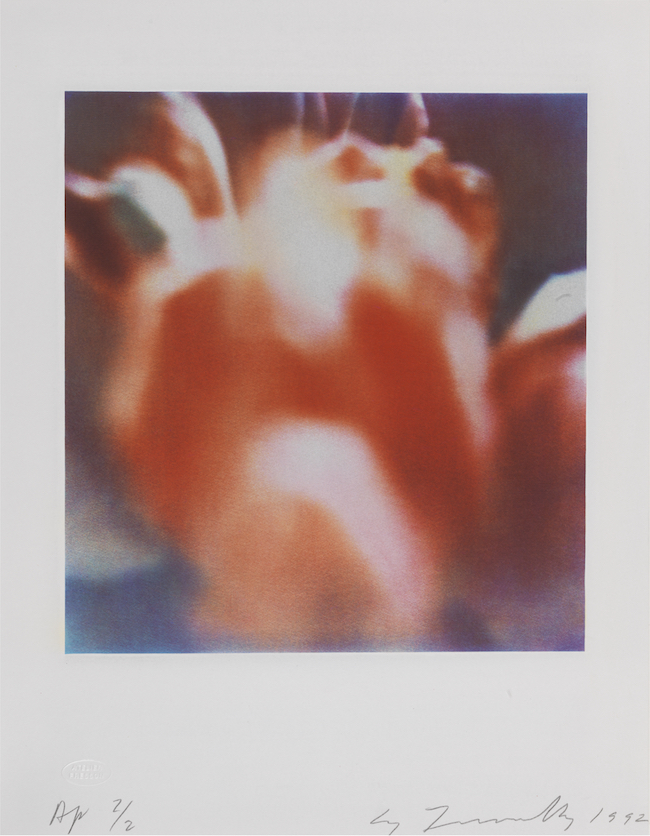

Cy Twombly »Tulips«, Rome, 1985, portfolio of 6 colour dry-ink photographs, each photograph 44.8 x 34.9 cm [H x W], edition: 10 + 2 AP, edition no.: AP 2/2 © Cy Twombly Foundation, courtesy BASTIAN Berlin

So, your own addition, which does not follow in your father’s footsteps?

I think my discovery of these antique pieces is also linked to my memories of our early encounters with the American abstract painter Cy Twombly, an artist my parents worked with intensively. He had a private collection of Greek and Roman antiquities, and I have many memories of those. But he kept them in a very different setting. He kept them in Italy, in his home in Rome and also in a place in the countryside by the sea. So, in a way, they were part of the Mediterranean world. Me having my antique pieces in Berlin is a different thing. It’s rather a contrast. Berlin is really a central European city with a northern climate, not to mention the differing architecture and Berlin being a modern, contemporary place rather than an ancient site like Rome.

I think mostly about the different light. You can’t possibly copy that light – there’s a certain light you find in Italy and Greece that you would never find in Berlin. I think we have a beautiful northern light, but it’s very different from the light in the south. And so, by having these pieces in Berlin, I think of them as sort of being almost in foreign territory. I feel it’s OK to do that, but I am aware that they are not where their roots are.

You mean, they’re no longer authentic in their current location.

Well, I think they still are authentic, but I’m aware that they’re not at home, so to say. So maybe it’s my responsibility as a collector to look after them while they’re not in the place they’re from originally. I feel quite strongly about this. Some collectors might just say that all these works have different origins, different countries and places they come from, and they’re gathered together or assembled at a collector’s home. But I do have a sense of these origins and where they came from in the first place.

Cy Twombly »Tulips«, Rome, 1985, portfolio of 6 colour dry-ink photographs, each photograph 44.8 x 34.9 cm [H x W], edition: 10 + 2 AP, edition no.: AP 2/2 © Cy Twombly Foundation, courtesy BASTIAN Berlin

You met Cy Twombly many times. What are your most vivid memories of him, what kind of person do you remember him as?

I would say he was a very modest, almost humble man with a great sense of humour. And quite a unique combination of European and American culture. He had his home in America and also the home he chose in Italy. He was someone who was capable of bringing these two different worlds together. And also bringing Italian and American friends together – people who would never have met if he hadn’t brought them together with his art.

He was an inspiration for you. Was he in some way also like a mentor to you?

Oh, definitely. He was modest in the best sense of the word. When I was still a student, we spent hours in Paris discussing literature, going to the Louvre. He never thought of me as just a student or someone whom he had met because he was a friend of my parents. He had this very open-minded attitude. That’s something I admired quite a lot. He would never look at people as being more important or less important; he wouldn’t even think of these sort of categories. He also lived away from the art market and all of what went on in the large commercial galleries. He didn’t really want to be part of that. Although, of course, he had to be part of that world, because it presented his work. But he didn’t want to be part of the whole phenomenon that comes along with the market. So, it was quite a unique experience to have this dialogue with him. Maybe I wouldn’t dare to say he was a mentor, but I was definitely influenced by him, by his approach to art.

Cy Twombly »Tulips«, Rome, 1985, portfolio of 6 colour dry-ink photographs, each photograph 44.8 x 34.9 cm [H x W], edition: 10 + 2 AP, edition no.: AP 2/2 © Cy Twombly Foundation, courtesy BASTIAN Berlin

I find it interesting that your return to the art world was in part promoted by Berlin’s surging art environment but you do not collect art from your own era. Or am I mistaken?

I do not collect the art of the present day, but I do have gifts, works of art given to me not by artists but by friends. I wouldn’t call that a collection, because it’s not artwork that I acquired from galleries or artist studios. Instead, it’s part of the friendship you can have with artists, the trades you can sometimes make with friends. You publish a book and maybe they’re very excited about it and they give you a drawing or… So it’s really part of that rather than looking in a more strategic way and trying to assemble groups of works, like a collector might do with a specific focus and maybe even a real target. I’ve never had that target; I think so much in terms of exhibition formats, catalogues and books that I wouldn’t be able to be so focused.

I think if you really define yourself as an ambitious collector, you’ve got to have that particular focus. Whether you collect from a certain period or a certain group of artists, or whether you collect in a more encyclopaedic way, you have to have a vision, a strategy. Maybe it sounds awful, but I think you have to have that in order to succeed – it’s a prerequisite for putting together an excellent collection. No matter whether the vision comes from yourself or from a highly qualified adviser, but you have to have it. And I don’t have that. So, although in a way I am a collector, I’m more likely to think of myself as a gallerist or an author. I think you can’t be both at the same time.

Speaking again about your family collection, what is your vision for its future and development? Does the collection itself have a mission of its own? Because on the one hand it’s been very closely linked with your father’s life, but on the other hand it’s an independent entity.

My parents and I feel that the collection should be accessible to the public; it shouldn’t be something that’s just kept privately. And that’s also one of the reasons we’ve decided to donate the building in Berlin (Am Kupfergraben 10, also called House Bastian – Ed.), which stands close to Museum Island and which we used for exhibitions for about ten years, to the Berlin State Museums. It will become an art education centre. We feel very strongly that through loans and collaborations with museums, as well as through donations, we can ensure that we really interact with the public and that even if the collection legally belongs to us, it should really belong to everyone, or at least be accessible to everyone.

I read that your father found it emotionally very difficult to part with this building. “The closer we came to signing to contract, the more we experienced the emotional connection,” he said in an interview with ArtNews in 2017.

It wasn’t easy, and it still isn’t easy because, having worked very closely with the architect, David Chipperfield, my father was really deeply involved in designing the building. For Chipperfield, it was more than just a commission; it was really something that they accomplished together. So it was a bit difficult to, well, say goodbye to this building. But I think it’s quite essential that we support the State Museums in that particular location. You’ve got fantastic collections of sculpture at the Bode Museum, you’ve got the fabulous 19th-century collection, you have a collection of antiquities including the Pergamon Altar, and you’ve got many other remarkable works. However, there was never any room for art education.

The State Museums were thinking about beginning a very ambitious programme of cultural and art education, but there wasn’t a suitable space on Museum Island. They considered several other locations elsewhere in the city, but that would mean that students would need to go to a different part of the city after visiting Museum Island, and then they would lose this link. All of us, including the directors of the museums and the president of the museum foundation, felt that the centre of art education has to be next door. So our building really is in the ideal location to do that. And that’s primarily why we decided to make this gift to the State Museums. We’re very excited about seeing its new function as an art education centre.

Cy Twombly »Tulips«, Rome, 1985, portfolio of 6 colour dry-ink photographs, each photograph 44.8 x 34.9 cm [H x W], edition: 10 + 2 AP, edition no.: AP 2/2 © Cy Twombly Foundation, courtesy BASTIAN Berlin

In a way, it’s your way of “giving back”...

Yes, I think we feel that we’ve had the privilege of working with some outstanding artists and that we should give something back to the general public and especially facilitate access to culture and the visual arts. We must remember that museums are not free of charge in Germany. Although there are reduced entrance fees for children and educational visits, most exhibitions are not free of charge. That’s something we will have to work on in Germany in the future. And the donation of our building is one of several crucial steps to make visual culture more accessible and to try to achieve a more democratic approach and open up museums to everyone. I think we should be very ambitious, and this new initiative should include the State Museums but also as many private donors as possible in order to really achieve something in the next few years.

Looking back at your family history, do you think your parents’ decision to open a gallery was a logical step in the development of their interest in art? Because, as you said, at first they were not involved with the business side of art.

That’s true. And for many years – actually until the death of Beuys – they did not have a public exhibition space. Because at the time my father worked almost exclusively for Beuys. He worked as his assistant and also as his studio manager, taking care of publications and museum exhibitions for him. After Beuys’ sudden death, he was faced with a new situation and, rather than working for one artist on a full-time basis, he thought about a series of exhibitions with several artists that he was close to. That’s how the gallery came about. But it didn’t start with a commercial interest in selling art; I think that just came later. To ensure that the gallery could be run like a proper business, he would have to sell works of art from time to time.

Did he also sell anything from his collection?

We try to keep that completely separate. We have selling exhibitions at the gallery, and then we have works we keep privately and loan to museums. We would not exhibit these latter works at the gallery or sell them off. We would rather buy something new than sell and replace an existing work. We would never sell in order to take something out of the collection. It would instead be an exchange. If we were to sell one work, it would be to be able to acquire another one. Just to keep the integrity of the collection.

The situation with the art market at the time when your father established the collection radically differed from the situation today, now that you’ve taken over the gallery.

It’s a completely different world. When I talk to my father about this, he always remembers that it was a very small circle of collectors when he started. Mainly European collectors and some serious collectors in the United States, but still it was this limited group of people who were interested in modern and contemporary art. In those first years, he never met a collector from Asia, Australia or India, and there was no global market whatsoever. It was really only western Europe and the United States. So that has changed. It’s a fully global art market today.

I’m worried about the increased inequality in the world in a general sense. I think many artists are concerned about that, too, and they’re aware that while their work can have a strong aesthetic impact on many people, it probably will not change the way the world is evolving. Many possessions are in the hands of very few people.

Have you ever discussed with Anselm Kiefer if he’s happy about the prices his artwork is selling for now?

Well, I would say that you can regard the art market as a sort of very strange, bizarre world. I assume that in Kiefer’s case the prices are high, but they don’t seem completely irrational in relation to the importance of his work. The issue of these irrational, almost unexplainable prices has also come up with the work of Gerhard Richter and his paintings achieving prices well beyond any expectations and maybe even beyond reasonable limits. Richter himself has questioned the price level his work has obtained and has found it a very strange phenomenon that’s out of his control. And that’s discomforting. I think Kiefer has not reached that height of very high prices. I think he’s reached a considerable high price level and not that world-record level that would make you question the market altogether.

Cy Twombly »Tulips«, Rome, 1985, portfolio of 6 colour dry-ink photographs, each photograph 44.8 x 34.9 cm [H x W], edition: 10 + 2 AP, edition no.: AP 2/2 © Cy Twombly Foundation, courtesy BASTIAN Berlin

But how do you feel as a gallerist in today’s market situation? What are your most important goals? For example, locating your gallery in London, just before Brexit, with so many competitors just around the corner?

I agree that the market is very competitive. I think the key to success is expertise. I’d like our clients to know that they can buy works with confidence and that they’re buying from a knowledgeable expert. Someone who knows exactly what the works are about, their history, the exhibition’s history and condition. In other words, having museum-quality standards at the gallery.

Although some of the artists we’ve worked with are no longer alive, we’re not offering secondary market works. We’ve got direct relationships with the estates and foundations preserving the legacy of those artists. I think it’s impossible to compete with the small group of galleries that have established a global presence. But of course you can offer a particular form of expertise that some of those galleries don’t have. They have a global network, but not all of them have actually worked with the artists as closely as some of our experts and scholars have. I think that’s a unique combination and that collectors value our particular in-depth understanding of what we exhibit.

Why was it so important for you to leave Berlin and be in London? Collectors travel globally nowadays.

Berlin is quite Europe-centred; we don’t have that much of a connection to the Asian countries, the Middle East or Australia and New Zealand. I’ve often been asked “Could we meet in London?” To which I reply “Yes!” In certain cases I was travelling here quite often, but I didn’t have a base, a real presence in London. That’s when I began thinking about a permanent presence, even an exhibition space here. It just grew out of these questions and conversations I had had.

As a gallerist, you probably meet collectors from various generations. Is there any difference in how they develop their collections, what they’re searching for in art? Many collectors today are quite active on Instagram and other social media platforms. Those tools have also completely changed the scene.

I think social media have made a huge difference in terms of making collections visible and transparent. There used to be quite a number of very secretive collectors. Some of them lived in remote places and others in the big cities, but without ever showing their artwork to anyone. This has changed, and many people have their works available online or in social media for everyone to see. They’re interested in showing and sharing instead of keeping it all to themselves. So I guess social media has changed and influenced the way people see art.

For the good?

I don’t know, because that sort of fast social-media communication can be a bit superficial. It’s something that’s good to have if it’s accompanied by other activities. And it will never replace printed catalogues or books. So, I think you can have that Instagram or Facebook presence for your collection if you still publish a book at some point. But it’s very disappointing if you only have an online presence, such as maybe an e-catalogue instead of a printed publication that you can actually hold in your hands. I still believe in the traditional way of publishing art and publishing art holdings.

Exterior of Bastian London, courtesy BASTIAN London. Photo: Luke Walker

We spoke about the accessibility of art and the situation with museums in Germany. But have you yourself found an answer to why you have this need to own something? You can go and see all these great works of art in a museum, for example.

This is one of the great mysteries of collecting and the deep longing or desire to assemble a personal collection. From a very rational point of view, I think it’s quite unnecessary; instead, I guess it’s something rather emotional. Perhaps because when you own something, you have access to it all the time. Maybe you’re sitting in your library at night and you remember that particular work of art, and you can just walk down to the basement storage, remove it from the cupboard, and have a look at it again.

To be honest, the privilege of owning art is a luxury; it’s not something that anyone needs. But to have access to art, to see, to enjoy art is not a privilege – that’s a human right. That’s why museums in many countries still have to improve conditions for those who are not privileged and can’t pay for expensive tickets all the time.

Do you think art has the power to change something in people?

Absolutely. I very much believe in that. I think artists have this creative energy that can change people’s lives and change the way they perceive the world, the way they see life.

Do you agree that all good art should end up in a museum?

I think what’s going to change and keep on changing is the way humans define the best art or the most important art. Think about artists who were very famous during their lifetime but are nearly forgotten today. So, that will still change many times. I also think that today we have an increased awareness of the ideal technical climate and light and security conditions. We’ve started to think about the long-term preservation of art. And, of course, a private home is never a perfect place. Think about paper – you might enjoy sunlight, you might enjoy living in a room with beautiful natural light, and that’s probably a very positive experience for you in your own home, but it could have a disastrous effect on drawings or photographs. In a way, it’s absolutely right to say that, beyond the personal enjoyment of art, the ideal place for artwork is a public institution.

For example, I suppose that Warhol’s Polaroids are very fragile.

Yes, they’re very sensitive to light. You have to reduce the light level when showing them, and even at a reduced light level you can’t display them permanently. You have to take them down after a few weeks or at the most a few months and store them and wait a bit before you can display them again. All of these matters can be handled much more efficiently by a museum. As collectors we can live with art for a limited amount of time, but we should be ready to think beyond that time and consider ourselves the keepers, but not the permanent keepers of these works of art.

What do you think is the main responsibility of a collector today?

I think we have some moral obligations, some of which are also legal obligations. I’m convinced that we must always remember we’re not the creators, we’re not the authors. We’ve acquired some fame, but I believe the creator should still be in control. I really value intellectual property very highly, so I think we have to be aware of the particular fragility of certain works and do all we can to preserve them and maybe lengthen their lifespan.

In brief, I think we must never be selfish with the collection. It’s always something that comes from the artists, and without the makers and the artists, there wouldn’t be a single collection; we wouldn’t even exist. And we must never forget that. It’s great to be a collector, but the artist always comes first.

Portrait of Dr. Aeneas Bastian. Courtesy BASTIAN