Advocate for Art

An interview with Swiss art collector Dr. Hans Furer

04/10/2019

Dr. Hans Furer hails from Biel, Switzerland, and has been running his law firm in Basel since 1988. He is a board member of several foundations with a focus on art, has headed the Art Galleries Switzerland association for 15 years, and serves as a judge on the Cantonal Court of Basel-Landschaft. Together with his wife, Monika, a Basel primary school teacher, he has been building a private art collection centering on conceptual art since the early 1980s. The greater part of this collection is being shown at Kunstmuseum Basel for the first time under the title of a Remy Zaugg picture “Schau, ich bin blind, Schau” (“Look, I Am Blind, Look”, through December 1st, 2019). He maintained a long-term friendship with the artist. The Furers have donated to Kunstmuseum Basel twenty-four of the artist’s works in their collection. The couple lives in Basle and in the Jura.

Rémy Zaugg, Look, I'm blind, look. 1997/1998. Photo: Julian Salinas

What was the trigger that led you to collect art? How did you develop this interest and what was your first encounter with art?

I don’t know whether collecting is a genetic predisposition. When I was in school I loved Swiss stamps and enjoyed the process of sorting and completing. I came into contact with art thanks to the Basel Kunstmuseum (as a student). But the trigger for me was meeting Doris and Jürg Im Obersteg, who owned one of the most beautiful private collections in Switzerland. Today, you can marvel at their main works by Picasso, Chagall, Jawlensky and many others at the Kunstmuseum. When I was sixteen, I encountered these paintings in the private home of the Im Oberstegs in downtown Basel. I thought, wow! One day I want to build such a collection too...

When did you decide to build a collection yourself? How did it grow?

At first, my wife and I bought pictures for our four-room apartment, which included Mimmo Paladino, Mirjam Cahn, Stephan Balkenhol, Rémy Zaugg... Fairly soon the apartment became too small. In 1989 we decided to acquire important works by important artists. First one by Rainer Fetting from 1980 at Galerie Beyeler. That picture was on display at the artist’s first exhibition at Antony D’Offay in London where Fetting had his breakthrough as a “wild youth.” The picture measured 210 by 160 centimeters and we had no place for it at home... Starting from there, we acquired additional works, until we met Rémy Zaugg. His theme is perception and he is a conceptual artist. Initially, that was lost on me, but with Rémy that changed dramatically. And so we collected groups of works by Zaugg, Kawara, Mapplethorpe, Ruff, Baldessari, and others. The idea was not to have a hundred pictures by a hundred artists, but groups of works by a select few artists. The catalog only covers sixteen artists. The process of introducing an artist’s position to our collection often takes many years. We never buy art on a whim. There was one work by Sol LeWitt that I wanted to purchase, but it took me at least five years until it was finally added to our collection. At the moment we are keeping a close watch on Franz Gertsch. His work has quite a lot to do with our collection: Patti Smith by Robert Mapplethorpe, “Johanna” von Andy Warhol. He “immortalized” both in about five pictures. Then a Franz Gertsch organically becomes a perfect fit.

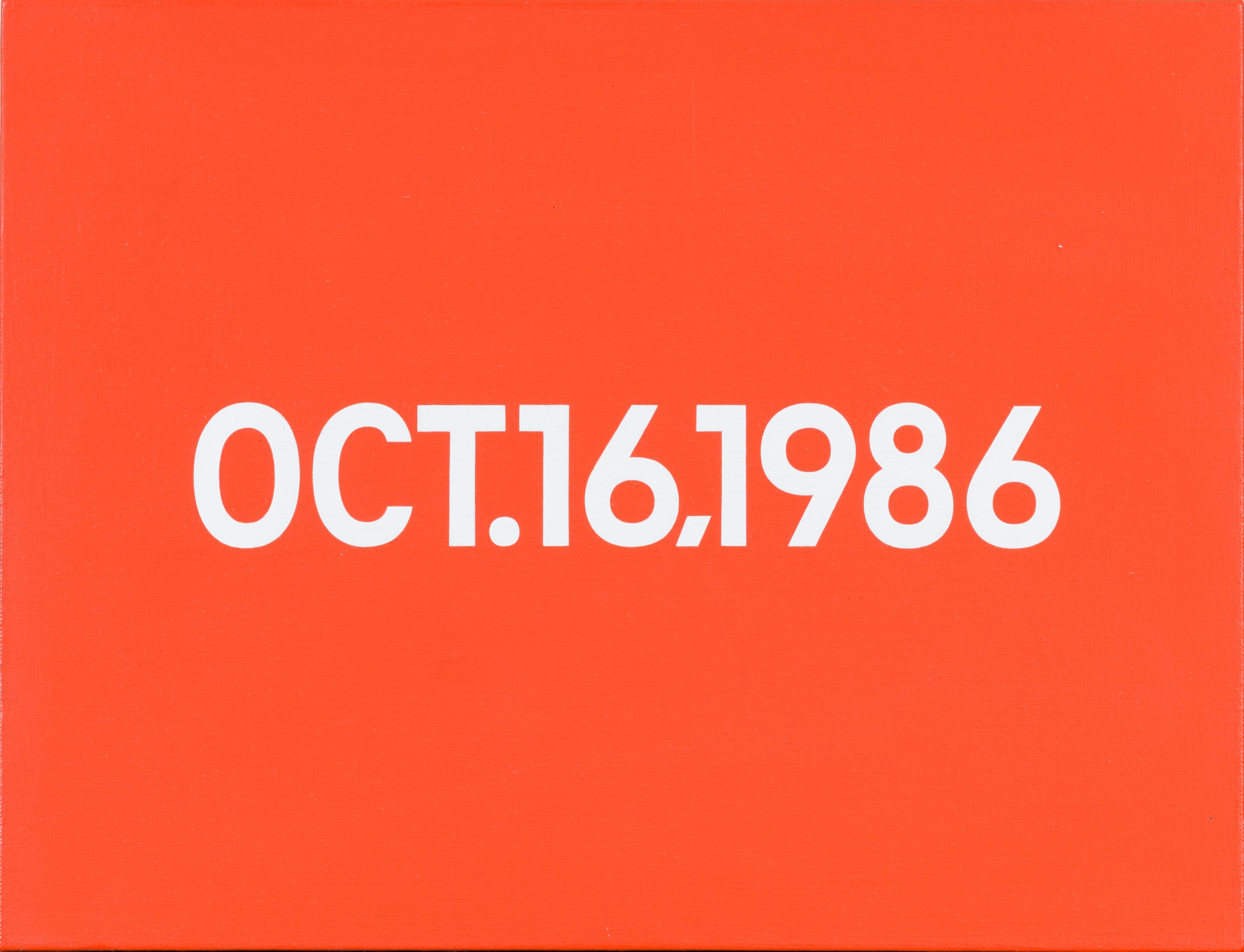

On Kawara, Oct. 16, 1986. 1986. Acrylic paint on canvas, 33 x 44.5 cm. Collection Hans and Monika Furer

What role does personal contact play for you — getting to know an artist? Does the art come first and the artist second, or is it the other way around?

Already in 1988 we got to know Stephan Balkenhol. We were among the artist’s first collectors in Switzerland. That led to our friendship. But the work of art always comes first, and the artist second. Friendships develop through the art. Our collection isn’t one that was purchased through Christie’s and Sotheby‘s, but at galleries (although we have bought art at both auction houses). That’s how our friendships with Thomas Ruff, Pia Fries and, above all, Rémy Zaugg came about. Rémy Zaugg lived here in Basel and we met at least every two months and frequently talked on the phone. For Rémy Zaugg I’ve also started a foundation.

Thomas Ruff, Portrait (K. Hewel) & Portrait (M. Graber). 1998 & 1989. Photo: Julian Salinas. © 2019, ProLitteris, Zurich.

What are the criteria you consider when you pick works for your collection? How do you arrive at decisions together with your wife, Monika?

The criteria are pretty simple — important works by important artists. It’s just that you don’t know who the important artists are and which works within their oeuvre are the significant ones. No consultant can tell you, you have to make up your own mind about that. In my case what happened was that I already developed an interest in art history in my youth and worked my way through the literature. I read a lot, from the Renaissance to Impressionism and conceptual art, and thanks to the city of Basel I also saw numerous master works at ART Basel, Kunstmuseum, Fondation Beyeler, and in private collections. It’s a privilege to be able to live in a city where art collections have reached such a high level. As Monika and I have been married since 1985, we walked that path together and acquired many a work of art together.

What period of 20th century art does your collection cover, and what media? How many works are there by now and will the collection be expanded? Are there new artistic positions?

We are the children of our times. The collection comprises art from the end of the1960s to today. In the 80s, Jean Christophe Ammann organized great exhibitions at Kunsthalle Basel and our collection is actually a “by-product” of what we saw there. It’s interesting that these sixteen artists basically belong to three generations. Monika and I were born in 1955 and 1957. One group of artists represented in our collection could be our parents, which includes John Baldessari, Andy Warhol, On Kawara, Sol LeWitt, Robert Barry. These artists were born a little before or after 1930. A second group is concentrated around the year 1945. That includes Rémy Zaugg, Lawrence Weiner, Robert Mapplethorpe, and Mirjam Cahn. And there’s a the group in our generation and there, of course, many of them are also our friends, including Stephan Balkenhol, Thomas Ruff, Pia Fries, or Jean Charles Blais.

Sammlung Furer. Photo: Tobias Dürring

What must a work of art “have,” or emanate, in order to catch you attention? What does quality mean to you, and how is it defined?

It’s hard to define quality in art. I think it’s more that there’s a sense of belonging to a group. Here, the positions we appreciate are represented by Galerie Mai 36 and Galerie Verna in Zurich, as well as the galleries of Konrad Fischer, Kaess Weiss, or Brooke Alexander. That has to do with aesthetics, and you move within that realm. If I’m a Baroque closet enthusiast, it’s going to be hard for me to get excited about Bauhaus furniture. In that sense, there’s no way of defining quality at all. In art, it has to be “developed” through comparison in museums, art halls, and galleries. Sometimes collectors get lucky and buy the “right” art – that’s what happened to us; sometimes they’re down on their luck. Still, it’s important to be able to stick to one's guns and acquisitions, whatever level that’s on.

What does collecting art mean to you personally? What does it mean to you to grapple with and appreciate art?

I think, in the end, it’s “meaning.” Some try to find meaning through religion, others through philosophy. I guess one can also experience meaning aesthetically and that, of course, is possible through works of art — and by having an original, you approach it in an entirely different manner. You have to buy it, you have to spend money, and that makes you think twice whether you want it and whether it’s really the piece you want to own. When you have a work of art at home it does really become a part of yourself.

On a dating platform you can look at faces and biographies too, but meeting someone in real life, that’s still something altogether different. There are collectors who want to be in contact with the artist and there are other collectors who don’t want any contact at all. That’s perhaps almost “spiritual” – because any contact leads to some realism, you’re faced with a human being and not an artist. Occasionally, actually meeting an artist can be rather disappointing. Sometimes you’ve imagined him or her to be quite different. Art and personality can drift so far far apart. That’s the reason why art collectors sometimes don’t want to get to know the artists.

With me, it’s different. I love to engage with the person too, but I have to say that the artists I know are all very nice people.

Sammlung Furer. Photo: Tobias Dürring

Is there a special story or experience that led you to a work of art. A story about how it was discovered, for instance, or how you came into contact with the artist?

We acquired the first work by Stephan Balkenhol at Galerie Mai 36. We knew that all exhibits were always sold out within the first hour. And so in 1988, we arrived at the gallery on time, and five minutes later we had decided which one we wanted. The gallerist told us that “it was already sold.” We were disappointed and opted for a different work; and in the long run, it turned out to be the far superior work. Or, take Andy Warhol. I’d always admired Franz Gertsch’s portrait of “Johanna,” and at an exhibition at Kunstmuseum Luzern, I suddenly saw that “Johanna,” but painted by Andy Warhol. I immediately called gallerist Bruno Bischofberger, and that’s how Gertsch’s “Johanna” was added to our collection in the form of Warhol’s “Johanna.”

How did you, as a private collector, arrive at the decision to show your collection to the public – why now?

Over the past twenty years, Kunstmuseum Basel has only once exhibited a private collection. It’s an honor for us, but there’s also a reason. We’ve decided to donate all our twenty-four Rémy Zaugg works to Kunstmuseum Basel. In order to show Rémy Zaugg in an international context, we agreed that other positions in our collection would be shown as well. That led to a wonderful show where you can clearly see that Rémy Zaugg is very much an international artist and on a par with Sol LeWitt, On Kawara or John Baldessari.

Sammlung Furer. Photo: Tobias Dürring

I’ve noticed that among the international collectors crowd there are relatively many legal professionals or people with legal training. How do you explain that?

My work as a lawyer and now also as a judge involves analysis, the dry wording of laws, and understanding rulings that are not always easy to read. It’s called legalese. Being able to comprehend such lines of thought doesn’t make you an art collector. But if you also possess some aesthetic awareness, these two qualities can be combined. I’m sure that’s one reason why many legal experts double as art collectors. And of course your income needs to be a little above average. In my case, I can say with a clear conscience that I’m not among the high-income earners of my trade, I simply began early and was good at buying works of art that we could no longer afford nowadays.

Were there ever works that you’ve parted from? Why?

What’s added to our collection stays in our collection. There are very few works that we’ve parted from, but it was always only in order to finance something else. It was never because we didn’t like it anymore, but because we wanted to acquire something else in its place.

What are your plans for the future of your collection?

Well, of course the main positions in our collection have been firmly established. And so it’s more about finding additions that make good sense, for instance an important work by Mapplethorpe or a special picture by Baldessari, and not to create lots of new positions or an altogether different collection. With the donation of the twenty-four works by Rémy Zaugg to Kunstmuseum Basel, along with the work by Thomas Ruff connected to them, we have set an important milestone.

Once a collector, always a collector — my outlook is informed by our history and for me, Swiss art is a hugely important position. Especially Swiss classical Modernism, artists like Cuno Amiet, Ferdinand Hodler, or Louis Soutter. Every country has its artists, and that has always fascinated me. I know many Swiss artists that have passed away and are unknown to most Europeans. I’m working on the following project: Along with Ferdinand Hodler, Cuno Amiet is one oft he most eminent Swiss artists. He was also a member of the “Brücke” group (Nolde, Kirchner, Pechstein, Mueller...). Some time ago, I bought the artist’s last self-portrait, and now one of his earliest self-portraits. He painted about 180 self-portraits in the course of his life. My goal would be to acquire one self-portrait each from five or six decades. I have the self-portrait of the twenty-two-year-old Amiet and that of the ninety-two-year-old Amiet, there are seventy years between them and I will now hang them next to each other. They wonderfully span a lifetime.

I don’t yet know what will eventually happen with our collection, I still feel too young for that. But we already know, of course, “the last shirt has no pockets.”

Sammlung Furer. Photo: Tobias Dürring

As an experienced collector of many years, what advice would you give today to a “young” collector, someone who wants to start collecting art?

For starters, that young collector would have to fill out a questionnaire, so that a clear path and a goal are established. Buying something that gives you joy and that you like seeing on your wall, that’s one thing; building a collection is another. The crucial thing is to not look at the market (what might gain in value), but to understand the artists of one’s own generation and find out, in collaboration or conversations with gallerists, art experts, and exhibition organizers, what the interesting positions might be. The key thing is to understand positions. In my mind, if you only buy because others have the same or have “recommended” something to you, you’re making a mistake. Father-figure consultants are good for a young collector, but fathers are, of course, also parents. Here, too, you have to make up your own mind and find out what suits you best.

If a young person today decides to buy art and visits an art fair for the first time, isn’t that overwhelming?

That’s the most difficult criterion. You have to be able to form an opinion. At the time, I formed my own opinion. Where has this artist had shows? Which curators have taken an interest in him or her?

In the old days, things were a lot simpler — those who had an exhibition at Kunsthalle Basel were passed on to another twenty institutions. Today, things are more haphazard. Every artist wants to “make it,” be present on the market, and reach the top. They all want to win the race… but there’s no way of knowing anymore who’s going to make it to the finish line. Anything can happen today, and that’s true for many systems. From my present point of view, we could also be headed for an overkill situation. While art was still elitist in the 50s, with conceptual art an effort was made in the 70s to usher in the democratization of art. Artists like Beuys, or Lawrence Weiner, who printed cheap booklets, or through the dissemination of graphics… Democratization then brought about a situation where actually anything became possible. Due to today’s strong art market, everyone wants to participate in that market and that could have an overkill effect.

For instance in soccer they always stage the world championships and FIFA keeps introducing new “vessels” to keep people entertained. There’s the women’s world championship, a European “Club Liga,” the “Nations League,” etc. They broadcast these games for more and more money. That can lead to an overkill situation, because people don’t want to cough up the bucks any more and everything repeats itself. So that, in the end, no one cares for soccer anymore. Something similar could be brewing on the art market, because there is so much art around the world and people start to think, I’m overwhelmed; and there’s no longer any art history either. To put it simple — I’m exaggerating, of course — people stop with Andy Warhol and will shell out 70 million for that, but a new artist isn’t even known anymore… and no one’s interested in him or her.

Sammlung Furer. Photo: Tobias Dürring

As board member of several Swiss art foundations, how do you explain that incredibly activity, that “Swiss passion for collecting,” meaning the high density of collectors?

In Switzerland we’ve always had this extremely high density of collectors. That’s not only due to economic reasons (Switzerland is a rich country), but also to the country’s small size. The Swiss have to leave their country and go to big countries, such as Germany, France, the US, England, now Russia, China, or others. Actively trying to understand other cultures and other approaches to art also gives you lots of “outsider's views.” These are often better than “insider’s views.” What’s more, we have a fantastic density of top-notch museums with the best illustrative material from all periods. And so, much like a pinball machine where the balls always go back and forth, this always touches off new, interesting contacts and provides inspiration, and that, of course, also boosts the art scene and the collectors’ scene.

You are also active as an artist yourself. How did you develop an interest in that?

Obviously my creative and imaginative powers are above-average – just look at those ornate expressions in this interview. I’ve put them to use for my own art. Actually, I first started painting and creating linocuts before I began collecting art. I am one hundred percent certain that it’s only the fact that I engage in artistic activity myself that gave me an understanding of art and enabled me to acquire the collection. I’ve had my own studio since I was twenty, I’ve painted some 800 pictures, made thousands of drawings, and to this day I haven’t tired one bit in further developing my work. For me, that eas always about developing my own artistic ideas and no one looking at my work would get the idea that it was derivative of Picasso, Nolde or Munch. It’s interesting that many artists have built their own collections. For instance Picasso, but also Baselitz and others. At the time of the Impressionists, artists were the first to acquire works from other artists (for example Henri Roussau’s works were admired, acquired, and even collected by the Post-Impressionists).

You have such a wide range of interests and engage in so many activities, in committees, associations, and foundations. How do you manage that heavy workload?

People often ask me that. You simply have to be extremely focused and concentrated – over and over. The other thing is, for everything there is a season. You have to take on jobs and let go of them again.

Are there other “passions” aside from art?

When it comes to my temperament, I’m a very active type. As a lawyer I’ve passionately represented employees all my life, the same goes for politics (as a parliamentarian), as well as putting my abilities to the test as a judge on the Cantonal Court. I’m no craftsman, that’s for sure, but our house in the Jura, for instance, has fifty-five windows. I clean every one of them once a year, and I enjoy doing it.

Hans Furer. Photo: Tobias Dürring