I had an epiphany

An interview with British art collector Stuart Evans

19/11/2019

Well-known London-based art collector Stuart Evens is a lawyer but looks like an energetic, good-natured hippie. The walls of his house are covered with lots and lots of paintings and works of graphic art. As he says himself, it’s very important for him to live with art. “I had what I would call an epiphany. I realised that I could, within my resources, buy a significant work of art by a young artist and make a difference for that artist and make a huge difference for my living environment.”

In the early 1980s, at a young age, Evans became a partner at the law firm Simmons & Simmons. He soon proposed to the other partners that “I could transform the offices with white walls and no additional lighting by buying contemporary art.” That was the beginning of the Simmons & Simmons corporate collection, which today includes a fine selection of artworks, including a large number of pieces by the Young British Artists. Evans acquired these before the legendary abbreviation YBA even existed.

Alongside the corporate collection, Evans has built an art collection of his own, which focuses not only on British artists but also on another abbreviation, namely, ABC. This is the name he has given to his own passion for art from Argentina, Brazil and Colombia. He has been travelling to South America for the last ten years. In fact, his son John and he had just returned from the region a few days before we met for this interview. “Most places I go to, one of my activities is looking at pictures,” he says.

Salon Style Hang at the home of Stuart Evans

You have a number of works by legendary artists here, on the walls of your home. For example, David Hockney. Do you know him personally? How did you, a lawyer, become a well-known personality in the London art environment?

When I was about ten years old, a great uncle, who was not related to me by blood, started taking me to museums and galleries in Newcastle upon Tyne. He was quite an international figure. He was a British architect who, in 1924, designed and built a bank on the Bund in Shanghai for a Japanese client. So he understood the international cultural and art world, and he taught me when I was very small that if you engage with the things you see and give them time, that can be life-enhancing. So I started appreciating art and being interested in art at a very young age.

In 1969 I moved to London. I rented a basement flat near to Portobello Road, and I very quickly realised I was living opposite David Hockney. But I was shy. I would see his boyfriend, Peter Schlesinger, in the dairy every day, and I would chat with him, but I never spoke to David Hockney himself. Yes, it’s a shame (laughs).

But I didn’t start collecting until I was in my thirties. As a lawyer, I had sufficient income to be able to do so on a small scale, and I started by buying limited edition prints by the artists whom I admired, such as David Hockney, Dick Smith and Howard Hodgkin. My Hockneys are from his Brothers Grimm series, made around 1969 when I moved to London.

Do you still have those prints?

We still have them here hanging in the flat. But...then I had what I would call an epiphany. I realised that I could, within my resources, buy a significant work of art by a young artist and make a difference for that artist and make a huge difference for my living environment. I suppose I started doing that round about 1990. That year I bought a group of drawings, monoprints, by Tracey Emin an artist completely unknown at that time. Around that time I developed a relationship with a gallerist in London whose name is Thomas Dane, and he helped me with my collecting.

I should make it clear that, as well as collecting for myself, I started collecting for my law firm in London, Simmons & Simmons, at the end of the 1980s. And it was very much the case that I was in the right place at the right time, because I could buy artworks for Simmons & Simmons before the YBAs were called YBAs. In 1997 Charles Saatchi had his YBA show, Sensation, at the Royal Academy; he showed forty-two artists. In 1997, twenty-seven of those artists were already in the Simmons & Simmons collection. We had early works by Tracey Emin, Angus Fairhurst, Damien Hirst, Gary Hume, Michael Landy, Sarah Lucas, Chris Ofili, Wolfgang Tillmans, Mark Wallinger and Gillian Wearing acquired during the 1990s on a budget of £25,000 pa. The firm still has those works, and I was very fortunate in that I developed relationships with the artists. Michael and Gillian are friends, and I’ve done various projects with Mark Wallinger. So, as I say, I was in the right place at the right time at the beginning of the 90s, when the international art world centred on London. It was all very exciting, and I was part of that.

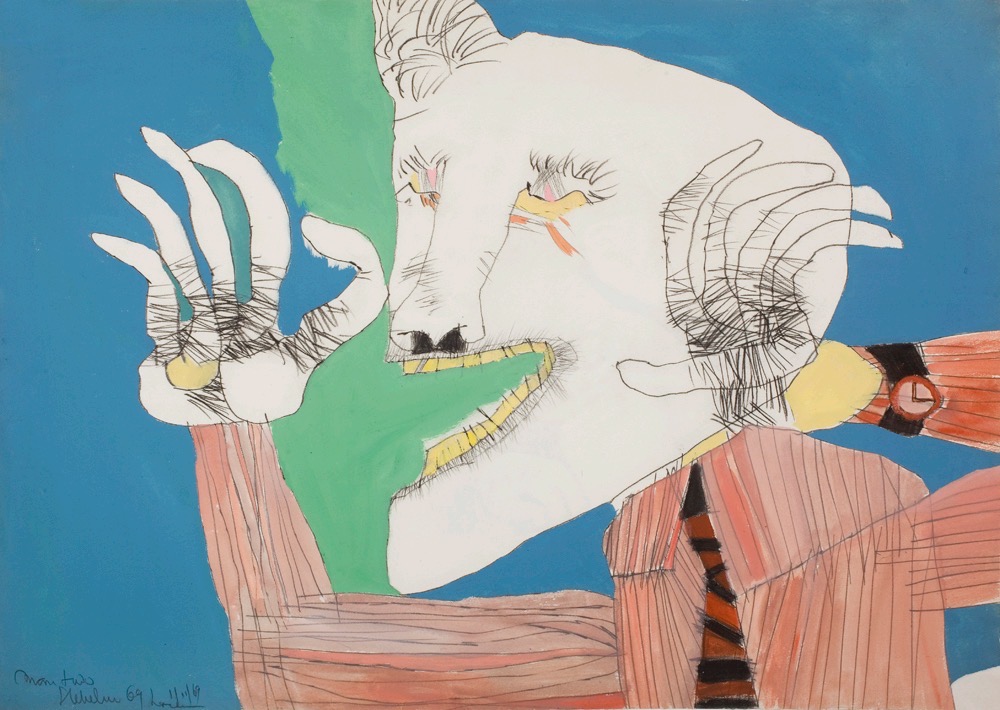

Work by Eduardo Stupia, Alan Davie, Powlina Olowska

London in those days was very different...

London in those days was very different. To find out about contemporary art you would have to research expensive magazines. What the YBAs did was engage with the general public, people who didn’t think they were remotely interested in contemporary art. Suddenly it was on the ten o’clock news; it was in the Evening Standard, and the people at Simmons & Simmons would say: “Oh, Tracey Emin! We’ve got one of those,” or “Look! Sarah Lucas – we have this,” or “Angus Fairhurst – we’ve got work by this artist.” And because it was becoming more and more within the public consciousness, there was a degree to which I developed stakeholders for the firm’s collection.

Is there any specific connection between the lawyer profession and collecting art? There are a huge number of lawyers in the field of collecting art.

Well, I would say that lawyers are not, on the whole, visual people. You know, maybe that’s a judgment, but that’s been my impression. When I started collecting art for my law firm, some of the investment banks had art collections: Deutsche Bank, S. G. Warburg & Co. Ltd, which became UBS, Baring Brothers, Robert Fleming. Law firms didn’t. And the way it began with Simmons & Simmons was that I made a proposal at a partners’ meeting. I was quite a young partner in the law firm...but I nevertheless dared to say that we shouldn’t approve a ghastly redecoration proposal that had been put to the partners. Instead I suggested that if I was given a small budget, I could transform the offices by buying and installing contemporary art. At that time, the London law firms had these 18th-century prints in their public spaces: hunting and seafaring and coaching scenes. They all had more or less the same sort of thing. So Simmons & Simmons was breaking new ground in the late 80s.

Nowadays, whether you’re a hedge fund or a hospital – what do you put on the walls? -contemporary art. It’s a given. But that was not the case at the end of the 80s, when I started.

Most law firms now have art collections of some sort or another. But what we wanted to do was to support young artists early in their careers by buying significant work on a limited budget and give them a showcase that was away from the galleries. Interestingly, quite a lot of artists at that time weren't sure that they liked the idea of being involved with capitalism and commerce and joining City collections. But I would say to them: “If someone goes to a gallery or a museum and sees your work, what would be a long time for them to look?” Well, two minutes would be a very long time. And I told them that we’d have their work in our conference rooms. The meetings go on for hours and hours, and the meetings are always partly boring. If your work is there, it will resonate in an entirely different way. People’s consciousness will be invaded by your work. The artists were persuaded, on the whole. And so that’s what I did.

Those pictures are still here and I continue to acquire new work.. It still tends to be emerging artists, because of the limit of my budget. But that doesn’t always mean young people. Some artists don’t emerge until they’re my age, seventy years old. So I’m buying work by much older artists but still within the budget, work by people who aren’t big names on the circuit. It’s never been trophy hunting. It’s always been trying to engage with artists and develop a relationship, but it’s always been led first by a picture, never by a name, always by a specific work of art.

Trophy hunting is an essential part of the art market nowadays.

Yes, and I suppose artists who are trophy names are pleased with that. But it seems to me that you can often spot a collection of trophies. It’s different from a collection where someone has engaged passionately with artists.

Does it mean that you, in some way, helped to market the YBAs?

I was one of the relatively small number of people in the UK who was actively buying. I wasn’t marketing in any direct sense, because we never sold anything. But I was told that the gallerists would say: “Stuart Evans is buying one of these” (laughs).

I was operating on a very small budget. Over the years, the Simmons & Simmons budget has been 25,000 pounds per annum, and my own budget, I suppose, was a little bit larger than that. In 2008, my son John and I were invited by the second edition of sp-arte, the art fair in São Paolo, to come and give a talk about collecting. We flew to São Paolo, and we also visited Buenos Aires. John said to me: “Do you realise there’s only one city in the world that has more football clubs than London? Let’s fly down to Buenos Aires and watch Boca Juniors play!” And we did, and we absolutely fell in love with Buenos Aires.

I returned from there last Monday. Since 2008 John and I have, together, been actively collecting artists from South America – the ABCs. A for Argentina, B for Brazil, C for Colombia.

Work by Fred Pollock

So, your private collection focuses on the ABCs?

This is the collection I’ve been building with John. The Simmons & Simmons collection essentially follows the footprint of the firm’s activities. The firm has more than twenty offices internationally. Nothing in North America, nothing in South America. So... for the firm I want, if possible, to provide an explanation for why we own this or that work in terms of the firm’s operations. For example, last year I bought a piece by Paulis Liepa from Latvia. The firm does not have an office in Latvia, but there are historical client connections between Simmons & Simmons and Latvia. In the past we’ve acted for the Bank of Latvia, and we’ve done a number of things with other Latvian clients. So, it made sense to have a Latvian artist.

The Simmons & Simmons collection is mainly European. Its core is British, but I think any collection that’s based on where artists come from doesn’t make sense in the international art community. The Turner Prize, the Tate prize for contemporary art, started life as a British prize. But “British” came to mean any person of whatever ethnic origin who had a practice in the United Kingdom or had made exhibitions in the United Kingdom.

Also, the Simmons & Simmons idea broadened over time. When I started, the art world was a small place, and I was buying almost entirely in London. But over the years I’ve been looking around Europe, for opportunities to buy things for Simmons & Simmons.

My own collecting has been British or South American. So, what I’ve collected is both what I would call “modern” - art made in the 1950s and 60s by British artists and by South American artists - and then the things that are being made today in the United Kingdom and in South America.

Is it even possible, in our modern-day world, to discern specifically geographical characteristics in art?

I don’t really think so. Two years ago, John and I went to India for the first time, and we visited the Indian art fair in Delhi. We agreed that the last thing we needed to do was to start buying Indian art. Okay, so we were going to look, but not to buy. But when we got there, we discovered art by these Indian artists – Astha Butail and Rathin Barman - that was closely related to art by Colombian artists which we had bought – Nicolas Paris and Mateo Lopez. The artists did not know one another but their work was so connected that we not only put the artists from these different continents in touch with each other, but we bought the Indian work (laughs).

In what way are they related?

I think by a number shared formal concerns. There’s quite a lot of art being made all over the world that I would say comes out of architecture or an architectural understanding. And it was quite striking that work we already had in our collection, which had an architectural emphasis, worked so well with things we were seeing for the first time by Indian artists.

Work by Juan Carlos Stekelman

Returning to corporate collections – there’s often a feeling that they’re missing something. A soul perhaps...

Well, like it or not, the Simmons & Simmons collection is all chosen by me (laughs). What we’ve avoided is purchase by committee. I think that can be almost fatal because...well, it almost always happens like this: “OK, I’ll let you have this picture providing that you let me have that one.” And there’s a lack of coherence. It’s based on compromise. Whereas I’ve been fortunate in that I’ve been given the freedom to buy. Yes, I have a group of people who look at what I’m doing. Yes, I have to operate within a budget and certain guidelines. But I’ve been given a lot of freedom over the years, and that has made the Simmons & Simmons collection what it is.

In 2001 you were on the panel of judges for the Turner Prize.

Yes, I was. It was the year that Martin Creed won the prize.

In one of his public appearances, curator Viktor Misiano provocatively maintained that art prizes are a provincial phenomenon.

I think the idea that “this is the best work of art here, and this is the second best” is not a strong idea at all. I think art prizes exist, primarily, to raise the profile of either a group of artists or of a particular way of creating. And to that extent they’re a good thing, because they raise the profile. But the idea of grading, I think that’s a little bit silly.

Another thing I would say about my collecting is that I’ve tried to encourage artists when they’ve gone out and started doing new things. I think that when an artist has a certain amount of success with a particular stream of work, maybe some galleries encourage them to stick with that because they know they can sell it. But the best artists are the ones who break the mould, and I want to encourage artists when they’re doing something different for the first time.

What’s the most important thing that young artists have to keep in mind? That is, if they’d like to get recognised in some way? There are millions of artists...

Yes, there are millions of artists and very few who make a lot of money. I’d say that what drives me in my appreciation is first art that has a cerebral engagement and second art that is...aesthetically pleasing. Now, I think I was not very different from most collectors: you start buying what you think is beautiful, and then you move on to buy what you think is challenging. I think that’s a very typical path.

What I’m buying is... I think about ninety percent of what I buy is two-dimensional work. It’s paintings, it’s photography, it’s drawings. To a small extent I buy video work. I’ve just lent to a festival a Mark Wallinger video called Threshold to the Kingdom. I bought the first in the edition when it came out. So I have some, but not more than half a dozen, video pieces. And I have some, but not more than twenty, pieces of sculpture.

Work by Sofia Neptuno

How many women are represented in your collection?

I think there must be around forty percent women artists in the Simmons & Simmons collection. Looking back, I’ve collected a lot of women artists. In my own collection... Well, in this room we see...four works by men and three by women.

Is there any difference between men and women in art?

No, not really. I don’t think you can say that there are gender-specific traits in art. And to me it’s...I don’t think I actively go out looking for minority art in terms of gender or sexual orientation or ethnicity. But just by looking at interesting things you’re bound to end up buying art that engages with issues of gender and sexuality and art by people of different ethnic origins. I think it’s still more difficult for some people to make and sell art than for others. There’s mainstream art, and then there’s something that’s going along beside it. And I wouldn’t say I’m evangelical about what’s going along beside mainstream art. I just want to engage with what I find interesting. And for me, it’s the aesthetic experience and the experience of being challenged in my thinking. I want art that provokes me to reappraise the way I look.

You mentioned the aesthetic aspect...

The aesthetics, yes. If you walk around, you’ll see. Someone once said to me that my collection has a palette (laughs): “You don’t see bright pink or vivid green. There’s perhaps a somewhat subdued palette in what you collect.” Okay, I had not really noticed that, but I can accept that that is the case.

As a collector, what’s the biggest challenge for you in today’s art scene?

There are areas that I have not gone into. I have not collected performance work. I would regard that as quite challenging. I’ve spoken on a collectors’ panel about artwork that has no permanence, work that will just degrade and disappear. The market has in a sense got around that by ascribing value to the certificate, so that the certificate enables the work to be remade. That’s quite challenging for some people.

Photographs are still quite challenging for some people, because they think, well it’s a photograph, it can be made again and again and again, so where’s the value? But I’ve never been properly driven by value. I mean, I know that some of the things I’ve acquired are now worth a lot of money. I’ve tended to be attracted by art that says “and you can take it home” (laughs). That is limiting, and so I guess I don’t accept the challenge of things which don’t have the component that you can “take it home”.

Personally, I have another big challenge. What I’m starting to do is to curate exhibitions, and I’m finding that very exciting. I’m curating an exhibition of figurative painting at Simmons & Simmons. It’s titled Memories, and what I’m trying to do is take artists of very different ages. The youngest is twenty-five, the oldest sixty-five, and with older artists I’ve asked them to lend a piece of their current work and a piece of their older work. And I think this is going to create a very exciting dialogue. There are maybe fifteen artists, most of them in their thirties, forties and fifties, but there are some younger and older than that. And it will be the way the art – which comes from different periods, but is all figurative art and is principally by artists from the United Kingdom and Argentina – how the pieces speak to each other. Just seeing the dialogues that start to develop as the exhibition goes up – I think that’s a very exciting thing. So, curating is now my challenge.

Work by Frank Stella

Is this your first exhibition?

It’s not my first, but it’s the most ambitious.

We live in a turbulent time. In some cases, art has been very active in a political and social sense. Do you think art has the power to change anything, or is it just an illusion?

I think that... Well, Banksy – an artist whom I’ve never collected – has made strong political statements that have resonated with quite a lot of people. So, yes, I think there are possibilities for artists to do that.

Michael Landy, whom I’ve collected throughout the years and continue to collect, is an artist who I guess would be regarded as political. In 2001 he destroyed everything that belonged to him in a former department store that he had hired on Oxford Street in London. And he was left having to attend his private view in borrowed overalls. I think that made a very strong statement. In his earlier Scrapheap Services piece, he created a virtual company whose mission was to dispose of elements of society that are superfluous to our requirements. And he did that, if my memory is right, not long after the Thatcher years.

So, Scrapheap Services, the piece acquired by Tate while I was chairman of the Tate patrons, was a huge hopper that was gathering up cut-outs of people, people whom society doesn’t need. In that, he was following in a tradition, and quite a British tradition, of cartoonists such as Thomas Rowlandson and James Gillray, who made very socially aware political cartoons. Landy has in some ways done that. I have a piece by him in my collection – it’s the spike that the park keeper uses to pick up rubbish while going around the park, set in a perspex cylinder. The spike pierces through cut out people and the title of the piece is We Leave the Scum With No Place to Hide.

As you mentioned, you were a member of the Tate acquisition committee. How has the role of art in society changed over the past few decades? Tate Modern is now one of the central attractions in London.

My committee years were 1997 to 2000. So that was the run-up to the launch of Tate Modern, which has been such a huge success in London. And what was really great, as far as I was concerned, was Nicholas Serota’s decision to include in the opening hang at Tate Modern so many recent acquisitions that this small group had facilitated.

I think art is a great thing because it has the capability of extending one’s understanding of the world in which we live. If you look, you’ll find great things. Is it a middle-class activity? Yes. Primarily because it means that you have surplus income, but you can buy wonderful things that will end up in museums for under 1,000 pounds. You still can.

What should a new collector keep in mind?

I think you have to take risks. I think the only way of learning what is good is to buy something and live with it. You’ll make mistakes, but that’s the way to get the confidence to go and buy something.

So what do you do? You do some research, maybe you establish what your budget is. Having said that, I’m afraid I’ve always broken my personal budget (laughs). However, having some idea of what you intend to spend, what you can afford, and where you’re going. If you’re going to end up buying several pieces in a year, having some kind of coherence. I think this develops over time.

But the first stage is taking a risk. The first stage is taking a risk and living with the piece. You can buy a small work on paper by a young artist and, as I say, sooner or later a museum will be asking you to donate it.

Work by Rob Reed