On a bicycle via the art world

An interview with Dutch art collector Alexander Ramselaar

12/12/2019

This conversation about art and collecting began in a very unusual way – Alexander Ramselaar had just returned a couple of days earlier from a trip to Bolivia. It was a trip he had taken on a bicycle. He was still, in the most literal sense, under the influence of the mountains and the high altitude. His red blood cells had not yet adjusted to life at sea level, and his eyes shone with that unmistakable glow of a person who has experienced the awesome power of nature and the feeling of infinity – of encountering it face to face and having been part of it. In addition, he had a new puppy at home who instinctively tried to bite everything in sight. Including the legs of guests.

If we assume that life is a journey, Ramselaar enjoys complex itineraries – in terms of destinations and modes of transport as well as art. Because that’s the only way one can get close to oneself and understand one’s “I” in a variety of dimensions, including that of the world as a whole. Ramselaar believes that art and travel complement each other. Both contain the element of unexpectedness, which, like the layers of mystery contained within the world, reveals to us ever new horizons. No matter where his path may lead, Ramselaar exists in constant dialogue with both of these passions and teachers of his, whether it’s projecting works of art on his retinas while traversing virgin landscapes or wandering the streets of a metropolis.

Ramselaar has been a passionate cyclist since he was a teenager, but he only turned his attention to art in 2000. Initially focusing on the art scene in his native Rotterdam, his collection has in the meantime expanded to an international scale. He collects art that has been created during his lifetime, and mostly the work of new, emerging artists. Some of the names represented in his collection include Diango Hernandez, Noe Sendas, Rossella Biscotti, Pieter Hugo, Edward Burtynsky, Lara Almarcegui, Gwenneth Boelens, Giorgio Andreotta Calò, Karel Martens, Yael Bartana and others.

A couple of years ago Ramselaar decided to turn his passion into his profession, leaving a successful 17-year-long career in the real estate and financial sector to become a partner to artists, designers and cultural institutions. He is a co-founder of Foundation C.o.C.A., which supports young artists in developing their careers. Ramselaar is also a board member at initiatives such as Geef om Cultuur, PAKT and Extra Extra.

Diango Hernandez, Fanatics

Is collecting art a journey of sorts? If yes, is it like a trek or more like a hedonistic vacation, for example, with the goal of enjoying city life?

I kind of have a problem with the word “collecting”, because it implies that you know what you’re after and you want it to be completed. Like collecting stamps, for example. I think those are the true collectors. For me, collecting art is like a constant journey. I think it’s also what I incorporate in my journeys in order to be open to the unexpected. New works of art or people who cross my path and give meaning to things can happen all of a sudden, or they can act in the long term. This is kind of a line that I see, something that I’m fascinated by.

But in the end it’s all about my own reflections. If you buy a work of art, most of the time it’s your own decision. But it’s also always a kind of a dialogue with the work, or with the artist, or with somebody else about the work of art. So it’s about meeting, sharing and exchanging, and that’s also what travelling is about. But you cannot compare the two completely.

You don’t need to read a pile of books to prepare for a trip. There are internet sites where you can get the necessarily information and then plan what you’re going to do. Like my most recent trip, to Bolivia. It was -15ºC or even -20ºC, but I was prepared. You can also watch YouTube and read blogs by other people. Travelling is more about the experience and meeting other people, and also sometimes about the unexpected. But if you’re collecting art or following an artist, there are many more surprises. New looks, new perspectives. I think there’s much more of the unexpected in art; you can be blown away in a minute.

So you’re saying there’s no Lonely Planet for the art world.

No, I don’t think there is. I mean, if you follow a guide like that, then it becomes really predictable. Sometimes when I’m walking through an art fair or a museum, I get the feeling like I’m walking along a familiar shopping street. Or at some collectors’ houses you see all the common, popular names. Like I also want to have this and I also want to have that... Sometimes I think it’s a pity, because in that case collecting becomes kind of predictable or well known, kind of a Lonely Planet thing. Of course, Lonely Planet is updated from time to time, because things do change. But unexpected: no!

So, as with cycling, not many people do it, especially not in the remote places where I cycle, so maybe there’s a kind of parallel between that and my way of collecting art. With cycling I’m also kind of walking on a side line.

Michael Wolf, Chicago

There’s the world of cyclists, which is like a community, and there’s the art world, which is also a kind of community. In which of them do you feel more comfortable?

For me they’re complementary. I’ve cycled all my life since I was fifteen, and I switched from cycling more mainstream routes to so-called bikepacking, which is very lightweight – you go into nature, you don’t destroy nature but you follow trails. It’s often in very remote areas, really off the beaten track. I know some people from the bikepacking scene, especially in America, and we share the passion of cycling, the joy of travelling. But if that’s all I had...

I think the difference with the art world – and especially meeting artists, curators or passionate collectors – is the element of the unexpected, the fascination with being surprised. But I think I’ve changed in the past five to seven years. At first I kind of followed the Lonely Planet track, with the art fairs and so on. Sometimes I still go to them, but nowadays I find it much more interesting to travel to Korea, for example, or to stay for two weeks in New York. To open it up like a time machine, to get to know a city through the perspective of art. By doing that you really get more into the genes or the roots of life.

Going into art in a broad sense opens up different senses; it’s more about reflecting on what’s going on in life and society. Cycling is more about experiencing. When you have to deal with a difficult route with a lot of climbing in it, it’s challenging; it challenges you in different dimensions. Like this last trip, which was really physically demanding, but because of that I experienced the landscape and nature and the endlessness of nature very deeply. Things like that make me more kind of zen.

While art, on the other hand, challenges you mentally; you have to interpret what you see. Most of the time you cannot directly give a meaning to something, because it disorientates you. That’s something I really like. And putting myself in a position to experience that. Because you can also choose not to do that.

I have works of art in my collection that question me about what I see during my travels. The pureness and the great power of nature, and how small we really are. But at the same time also the battle of people wanting to conquer the world, to understand it, to go into the magic of nature, to try to dig up all its secrets. I think there’s a part in all of us that likes to do these things in order to create new horizons. But at the same time it’s also kind of a way to find solutions for problems that we’re facing with the environment or other contemporary issues. Quite a few artists that I follow and also works of art that I own deal with this battle. Recently I read a book about the visionary German naturalist Alexander von Humboldt (1769–1859). It’s fascinating that already 200 years ago he started questioning the consequences of industrialisation.

Do you think about art when you’re in nature?

Yes. Not all the time, but yes. I associate a lot with what I see, with what it opens in me. And sometimes I also project works of art on my “screen”, mentally and physically. And the funny thing is that when you see them again in real life, they’re even more powerful.

I have a work by Giorgio Andreotta Calò that freezes a moment of time in the processes that are going on in nature with people involved. I had that experience also recently in Bolivia, when I looked at the volcanoes. I saw the ice and I needed water to survive, so I had to purify it and filter it. Calò captured that, also with the influence of humans, in a single work of art. And while I was there, I tried to grasp what was in fact going on. The water from the sky freezes to ice at the top of the volcanoes. The sun melts the ice, and then it flows down to the ground, where I can capture it to survive. What I like in artists is that they can materialise something into one work. Something you cannot grasp or understand in real life, but they can.

Giorgio Andreotta Calò, Clessidra

Isn’t it true, though, that nature is in fact more powerful and mysterious than art? And it’s not within our power to compete with it, whether in beauty or complexity.

I fully agree. But it’s also about how you define nature. When it comes to nature, humans like to place themselves outside the scene, while in fact we are a part of nature. But if you isolate people from nature, you also isolate art. In the end, art is always a reaction to or a reflection on nature. And also a way to unlock and dig under and understand better.

Do you agree that an artist is in some way a shaman?

I think it’s an open playing field, and I think in all cultures people want to express and reflect and create things and ideas that you cannot say in words. Nature doesn’t create such a playing field for itself as people do with art.

So you could say that with art, people are creating some kind of playgrounds, playgrounds for adults.

And they’re not per se functional. I think they’re functional in a spiritual way, but most of the time they’re practically useless. Whereas if you look at the processes in nature, nature is more like the engine of a car – everything has a function and works together with all of the other parts, and abundances are cut out. That’s a big difference.

But speaking about environmental issues and climate change, the rainforests in the Amazon are burning right now. There are more and more artists working on the border between art and social activism. Do you think art has the power or the voice to change anything, to change people’s mindsets? To change their attitude?

I had a discussion about the function of art, the impact of art on society, and also the reactions to budget cuts for art here in the Netherlands. An artist friend of mine said: “There are two things. One is that if there’s any kind of uproar or a revolution or big changes in society, most of the time artists – and also journalists, writers, etc. – are the first people to be muted. They are prohibited to speak, write and so on. And the second thing is that when you look back, you see that with all the Ryanairs and Easy Jets taking us everywhere around the world, most of the time what we’re looking at when we go to these cities and places are the remains of what these people created.”

So yes, I think artists are usually ahead of the times. They sense what’s happening. Not in the sense of finding the truth, but they sense, they create, and they set something in motion. And of course, this can be radical, but it can also be very subtle. That’s what artists do.

Pieter Hugo, Martin Kofi, Wild Honey Collector

But do you think people are listening to artists nowadays as much as they did before? Because there’s also an opinion that the voice of art itself is not as strong as it used to be.

By itself, no. I agree. But I think artists and art are moving into other domains much more these days. Especially the younger artists, I feel that they think in a much more interdisciplinary way, less about just one field specifically. I think the trend is that art is more integrated and therefore maybe also less visible, or less present.

There’s also a viewpoint that digitalisation and artificial intelligence could completely change the way we look at and approach art.

They do, but I think I’m more of an old-school person. Because what I like is what I can see, what I can feel or even touch. Over these past years I’ve bought more sculptures and installations. For me, that’s still one of the purest forms of art.

Did you have any interesting encounters with art during your recent trip to Bolivia? Any unexpected discoveries?

Not art or artwork in and of itself. But I saw many beautiful landscapes in Bolivia. For me, it was more than seeing just normal nature. The nature there took me to a kind of higher ground, as if I was looking at abstract paintings. There are so many minerals in the mountains there that they looked almost like paintings. And the lakes, the mineral suspensions of arsenic and other minerals turn them deep blue and a strange shade of green. I had a really surreal feeling, and it blurred in front of my eyes to become a truly physical experience. But at the same time, I cannot put my finger on exactly what it is. It becomes abstract for me.

Edward Burtynsky

For you, is art more of an intellectual or aesthetic challenge?

I think in the end it’s a combination. Most of the time, the starting point is the work of art itself, what the eyes see. It should have an attractiveness to it, otherwise you can just go read a book instead. For me the strongest works of art and the works that stay fresh in my mind over the years have a combination of aesthetic aspects – what you see – and at the same time the content or the conceptual meaning. A work must challenge me to think further.

Ten years ago, I had a different mindset; I was much more aesthetically orientated. And I’ve also had a shift in the buying process, because initially I often made instant decisions. But in recent years it has become more about seeing something, but also reading about it and talking about it, and only then do I come to a decision about whether I want to have certain works of art. The process of acquiring the work has become much longer.

So, I think there are two steps. One is the aesthetic and the physical experience. And the second step is the “what does it mean?” – is this something I want to have a dialogue with for a long time?

Have you understood why you have this need to own art?

It’s the daily dialogue.

But you could just go to a museum or somewhere, couldn’t you?

Yes, and for most of the artwork in museums, I’ve been there and been impressed by it and the memory of it has stayed in my mind. And that’s a good starting point for exploring new artists and so on. But the daily dialogue is something completely different. Just like with travelling. I’ve cycled routes that are like only 250 kilometres in six days or whatever. You can also do the same distance in a 4x4 in half a day. But by cycling you get so much deeper into the experience, and it also brings you into a different mindset.

Of course, there are various theories about collecting, about owning and all those masculine things. Sometimes you also feel kind of spoiled – being in a position to collect art, you sometimes feel kind of guilty, although maybe that’s not the right word, but you’re taking something out of the public space and bringing it into your own private space. That has motivated me to open up the collection more. It’s a way of sharing, a way of bringing the art into a broader space than just your own private space.

Rosella Biscotti

It sounds like you have an ongoing discussion with your ego about these issues. Because on the one hand you’re spoiled, but on the other hand you feel guilty...

And at the same time fascinated. Because many people in my environment would say “enough is enough”. Many people in the world where I came from, like real estate and finance, don’t understand it.

Four years ago, I moved to a new home. My former home was a little bigger and had higher ceilings, but this place has many more windows. So, I had to choose. Some of the bigger works of art didn’t even physically fit into this house. And also, with moving all of the works of art and all of them passing through my hands again, I was thinking to myself – man, what all do I have? So, I’m kind of de-collecting now. I also decided to bring some works of art to museums. So, one work went to the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, and just a few months ago about ten works went to the Stedelijk Museum Schiedam. I’m also in talks with some other places right now.

I also changed careers during this time. I’ve started working fully in and for the cultural sector, so my earnings have also decreased. But every year I buy some works of art. So yes, art is a kind of addiction.

But your main focus is still emerging artists?

Yes.

Has it been like that since the beginning?

In the beginning I relied a lot on intuition. I was also not really focused. When I look back, some of the works I acquired then still seem really striking, but others not so much. With some exceptions, I think about 90–95% of it is contemporary art. And that’s also what fascinates me the most, because it’s fresh and it’s a reflection on the time I’m living in right now. It gives me emphasis and challenges me to understand the world better.

But what I do more now is that I go deeper into the oeuvres of artists. Especially in photography. Ten years ago, I would buy one work out of a series, but now I say no, if I buy something, then I want to buy the whole series. Also, the process of buying has become much more intense because I really, really have to make choices. Not that I was very rich seven or eight years ago, but I had a bit more play money then, which is gone now. But at the same time, it makes the process of researching, thinking, weighing, balancing, etc. much more intense. And much more rewarding in a way.

Michael Wolf, Chicago

You also co-founded Foundation C.o.C.A, an organisation that supports young artists.

C.o.C.A is about our shared addiction, the thing that unites us – we’re all collectors of contemporary art. We have a nice scene here in Rotterdam, and the other founders and I were regularly meeting each other, we’d drink a beer together every two or three weeks. Each of us came from a different direction, but we all felt that we could go on buying works of art individually and making decisions ourselves. But opening up the process of acquiring art is a completely different challenge. If I do it myself, it all happens in my own head, it happens here, with my gut feeling. But if you do it together, you have to express what you think, what you feel, what your opinion is. And that becomes a really nice process of debating about art, about artists, about the meaning of a work of art.

So yes, we started with five collectors, and we’re already preparing for our 10th edition now. In the beginning it was quite difficult, because we had to figure out how to find the artists. We first thought of putting an ad somewhere in a paper or whatever, but someone from the institutional world said that we shouldn’t do that. Because we’d get 100 or more applicants and would have to answer them all. So, we decided to ask a curator to make a selection of three to five artists. We don’t have a lot of criteria; we mainly focus on artists who have already shown something but want to take the next step in their career. And in fact, that’s also how we choose a curator – we look for somebody who has shown something but is still not a curator at the state level. So, we also want to facilitate a platform for curators.

The curator comes up with three, four, five suggestions, and then we as C.o.C.A decide who from the short list is the winner. We reward the winner with an amount of money, which differs every year, because it also depends on the work. If it’s painting, the production cost is not so high, but if you’re making a video, it’s higher. So, we give a commission and we give the artist a platform during Art Rotterdam. We also organise an exhibition.

Are the C.o.C.A. artists and curators mostly based in Rotterdam?

No, we have a national focus. However, her or his practice should be in Holland. And the funny thing is, when I look back on the ten editions we’ve had now, I think we’ve had three Dutch artists. Seven of the artists were originally from abroad, but I think all seven of them still live and work in Holland. Which says something about how international the world is.

Returning to your own collection, I read in one of your interviews that it’s not always important for you to know the artists personally.

No. I know collectors who almost want to interview the artist as one of the steps before they acquire their work. That’s not necessary for me. But most of the time a kind of relationship does begin; you meet the artist and you might have something in common. It could be ideas or views or whatever. I also know quite a lot of artists whose work I do not own but with whom I might have a beer together. It’s like with a girl you really like but you’ve never had sex with her. Here you don’t have the artwork. It doesn’t influence the friendship really, but sometimes I feel a sense of unfulfillment in the relationship on the part of the artist. But almost no artist will admit to that.

Ed van der Elsken, Cuba

Do you follow the market? Is the market value of the artwork that you collect important to you?

Not really. Of course, it’s nice when you hear that the artwork does really well, but I’ve also seen the opposite over the past twenty years. I mean, I had a photograph that I bought for maybe 5000 or 6000 euros. Then some years later it went on the market for 25,000 euros. And then a few years later it was maybe 2000 or 3000. For me it feels like Mickey Mouse money. The market isn’t my focus; it’s not my interest. But it is nice to hear about. It’s a bit of a boy thing – hey, you did well!

Also, with a certain sort of people you always hear the success stories, but they don’t talk about the fact that their storage is full of stuff that’s worthless in terms of money. I also have works here that are now worth less than what I paid for them, but that doesn’t lessen their value for me. It’s all about the work and what it does with me. Sometimes when you buy more expensive works of art you don’t look at their market value, but you do inform yourself about them a bit more. You don’t use market value to guide your decision, but you are a bit more conscious.

Several gallery owners have said that in recent years the new people getting involved in collecting art seem to be getting younger and younger. If ten years ago the average age of collectors was about forty or fifty, today it’s more like twenty-something. Would you agree?

Yes, what I observe here is that there was an older generation, and I’ve followed it more intensely now for about ten or twenty years. There’s kind of a starving race of people following everything, really informed. And at the same time, I see new people standing up. I think at the moment there’s a broader group of younger people who sometimes buy art. Fewer people who do it really intensely, but a bigger group who make occasional purchases. But I’m also getting old myself; I’m 50 now.

Is that why you follow young artists, to keep yourself young?

(Laughs.) But what I do see is a kind of crisis in the market, like you have the really big galleries becoming more mainstream. I mean, if you go to Frieze or Basel nowadays, maybe 50% is the same. And it’s really, really difficult for young galleries to succeed. The old race of collectors went into a relationship with the gallerists, but nowadays I think that’s less the case. It’s much more difficult to attach to, to build up a lasting relationship with buyers for galleries.

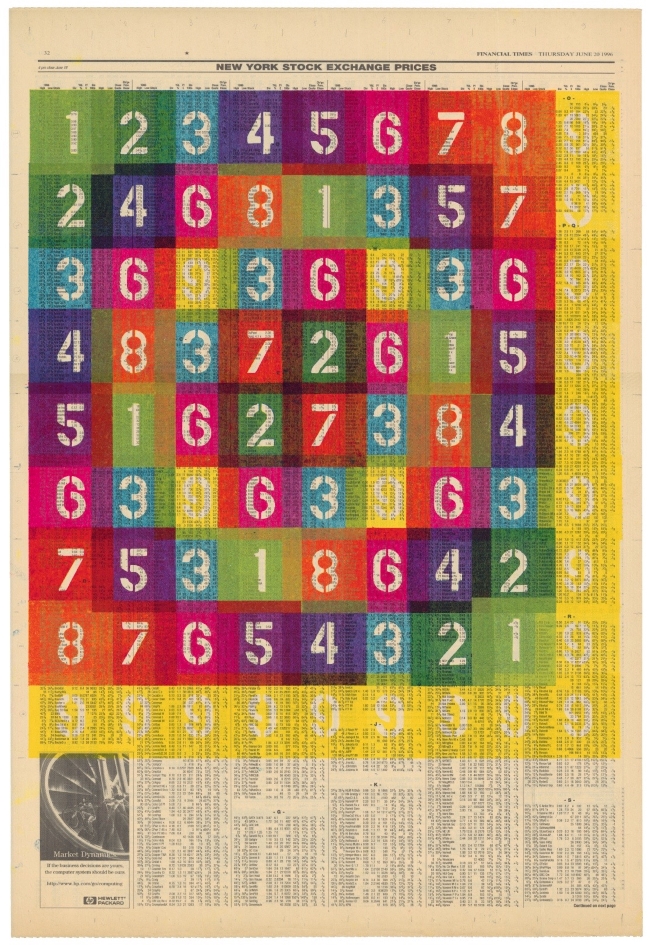

Karel Martens, Magical Square

Returning to travel. What do you think could be the destination of your collection?

Over the years I can say that I’ve become more conscious about two lines of thought. One relates to something that happened about six or seven years ago. I was reading one of the art magazines, and in it was the definition of the Anthropocene epoch. I didn’t know what that was, so I started googling, I went through my internet data limit, and then I thought hey, here I found something that defines what I’m kind of looking for and am fascinated by. And the other, and completely different, line is about children and young adults in a changing society. And most of the time that materialises in a fascination for photography.

I also see in my life that I’m either in an urban environment or I’m in nature; there’s no grey area between the two. And the destination for me feels like a path to understanding better and giving guidance. I think that there is a reason for trying to unravel that kind of a coat, whether it’s really human-like or really nature-like. Or in the confrontation between the two. That’s what gives me much more understanding and a consciousness of what’s all around us.

Seven years ago I more or less said goodbye to business life and started my own practice. Still in finance and real estate development, but fully focused on art institutions, artists, designers and collectives. So, I adapted my work to my passion. And if you would have told me ten or twenty years ago that that’s what I’d eventually do, I would have said you’re crazy. But this change also changed my lifestyle, because before that I only had evenings and weekends to devote to art. Now it’s kind of a daily life that I’ve stepped into. And I think I’ll spend the rest of my life here, in this world, in this dimension of people who feel the urge to create. It’s a free world and one that I really like to be in. Not as a creator myself, but more as a facilitator or connector. That’s the destination that I feel for myself and in terms of my working life – to be a bridge between the artists’ world and the other worlds.

I’ve also stepped more outside the cocoon of only contemporary art. I go to films much more often now, and I consume art in many more ways than I used to. And because of my work, I’m also involved in theatre productions, with musicians, with designers. So, I think I now have a much broader overview of the art world.

But that was a brave decision you made seven years ago.

It felt logical to me. Many people said to me how can you make a business out of that? Not in terms of becoming rich, but in terms of spending your life as you like.

But you managed it somehow.

And it’s really rewarding and satisfying. Absolutely.

Maybe at some point in our lives we all understand that we need less.

Yes. I especially recognised it while travelling, that you can survive with almost nothing. Being in a remote area with only my Kindle, and I’m fine. Less is sometimes more. But then at the same time, why should I buy art? It’s a contradiction.

Alexander Ramselaar