The oasis encouraging artists to step out of their creative comfort zones

An interview with French art collector Jean-Louis Haguenauer

Over the past ten years Marrakesh's contemporary art scene is making a a growing impact on the world cultural map, clearly marking the city as an international crossroads and the continent’s hub for contemporary art. One of Marrakesh’s main drivers is definitely the Montresso* Art Foundation and its artists’ residence, the creative experimental laboratory and art space known as Jardin Rouge. The complex is located among the olive groves about half an hour’s drive from Marrakesh, and the last section of the road winds through a classic Moroccan village. If not for the slightly strange, bright-red house cum art installation in the distance, this would definitely not seem like a place where one would go in search of contemporary art.

Jardin Rouge is currently closed to spontaneous visits and only open by prior reservation. In part, this is done in order to not disturb the flow of creative inspiration for the artists working at the residence. A private initiative of French art collector and patron Jean-Louis Haguenauer, Jardin Rouge opened in 2009. The property feels like a republic of its own and, without having to exaggerate much, one could even say that it borders on being a creative paradise.

Montresso Art Foundation, 2019. © Cyril Boixel

Jardin Rouge has eight artists’ studios, and each year it hosts about thirty artists of various nationalities from around the world. The goal of the residency programme is to provoke, encourage creative experimentation and challenge artists to step outside their comfort zones. To accomplish that goal, the residence provides them with all of the basics: accommodation, meals, studio space, tools, materials, opportunities for professional dialogues etc. The city and its accompanying noise and temptations are far away, while the bright colours and clear blue sky of Morocco stimulate the professionally-based creative hooliganism that goes on here.

Over the years, Haguenauer has supported many street artists, and he even tried his own hand at graffiti as a teenager in the 1960s. It comes as no surprise, then, that a large proportion of the artists in residence at Jardin Rouge likewise have a background in street art. But street art is definitely not the main focus here. Jardin Rouge has hosted young artists as well as already recognised artists working in a wide range of media. In addition, the residencies are often not only a one-time affair. Haguenauer highly values personal contact and forming a relationship with artists, and his own art collection does not contain a single work of art whose creator he has not personally known himself.

Many of the Jardin Rouge artists have returned here several times. Such as German artist Hendrik Beikirch, whom I meet in the studio when I visit the residence. He is known for his gigantic mural portraits of anonymous people he has met on his journeys to some of the world’s current hotspots. Each wrinkle can be seen on the faces he paints, and their stories embody such emotion than no words are necessary. Beikirch has just returned from Damascus and is working on a portrait of a young boy holding an automatic rifle. He tells about the families he met who are fighting on different sides of the war: “The most paradoxical thing is that fathers on both sides say one and the same thing: that they’re ready to destroy the enemy on behalf of a better future for their own children.” Then he adds sarcastically that since its partial opening to tourism, Damascus has become a destination for “Instagram tourists”. “They arrive, take pictures in front of the ruins (naturally, they’re not allowed into the real war zone), post the photos and leave. That’s the reality of our time.”

The collection of the Montresso* Art Foundation consists of work created by artists who have participated in its residencies. In the near future, it plans to build a museum to hold both the foundation’s collection and Haguenauer’s own private collection.

Thanks to the Montresso* Art Foundation's innovatively respectable place on the global art map, it is visited by art collectors, curators, art critics and representatives of art institutions from all corners of the globe, thereby providing an international network that many new artists have a difficult time reaching in their home countries. In 2016, the Montresso* Art Foundation opened a 1300-square-metre exhibition space on the property, which was designed by Haguenauer himself. Architecture is one of his hobbies. Each year, the gallery hosts at least three exhibitions. Falling Selfie, a four-metre-tall steel sculpture by French artist David Mesguich that takes an ironic jab at the neuroses of our day, has found a permanent home in courtyard at the Montresso* Art Space.

Haguenauer, who is dressed in bright yellow Converse shoes and a shawl befitting the January sun and morning chill of Marrakesh, has a bit of a mystical aura about him. He is open yet at the same time elegantly reserved. He was born in southern France but nowadays spends most of his time in Marrakesh and Moscow, with which he has had close business ties since the 1980s. Perhaps that is why, at Haguenauer’s suggestion, our conversation takes place in Russian, each with our own accent. He tells me he has visited Latvia once – the port city of Ventspils in the late 1980s. As of yet, however, no artist from the Baltic states has been at Jardin Rouge. Maybe this interview will serve as wonderful inspiration to correct this fact in the future.

Jonone, Un rêve plus long que la nuit, 2017. © Fanny Lopez

How did your relationship with Marrakesh begin?

It began a long time ago. I’ve been going to Marrakesh for fifty years already. I had friends here. I took my first trip to Morocco in 1970, and to Marrakesh in 1972. I bought my first property here twenty-five years ago. Parallel to that, I began working in Russia in 1981. So, although I’m in France relatively often, I do not live there anymore. At the present moment, I live between Moscow and Marrakesh.

We began the Jardin Rouge project in 2009. As an art collector, of course, at the beginning I bought many things simply because I liked them. I bought my first painting at the age of twenty. When I look at these works of art today, I realise that everything has changed. My sense of taste, my feel for art. But two things have remained the same: I’ve always loved bright colours, and it’s always been important for me to buy artwork by artists whom I’ve personally met. It’s one thing to see a work that an artist has made; it’s a completely different thing to see how he or she works and being able to follow that process. Then you immediately feel how genuine or not genuine the person is. Because there are artists who have technical talent, and then there are artists who have artistic talent – they’re two completely different kinds of talent. When you have this connection with the artist, then you get a close-up view – from the kitchen, so to say – of what the artist has done, and possibly also understand his or her development.

That’s how I’ve gotten to know very many artists. Both in France and in Russia. For a time we had a project in Russia through which I helped young street artists. They were going through a difficult period, with constant trouble with the police. Most of them were students – some were architecture students, others art students. My precondition was that I’d help them as long as they continued their schooling and did well at school.

In 2002 I bought the piece of land where Jardin Rouge is now located. It looked the same as everything else in this area: palm trees and desert. I gradually began transforming it and adapting it to the needs of the foundation. The first artist we hosted in the newly established residence was one whom I had previously helped in Russia. He was from Yekaterinburg, in the Urals. As of the present moment, we’ve already hosted eighty artists from a variety of countries.

Was beginning this project with Russian artists and street art a conscious conceptual decision?

It was a coincidence, it just happened that way. At first, the Jardin Rouge residence was only open in the summer; now we work eleven months out of the year. Yes, it all began with street art, because it just so happened that I had helped graffiti artists in Russia very much. And still today we are, of course, interested in artists who have a street-art background. But also other artists. We’ve had quite a few artists from Africa at Jardin Rouge. The 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair, which also holds editions in London and New York, has been taking place in Marrakesh for several years now. It focuses exclusively on work by African artists, and we take part in that every year, too.

One could say that Marrakesh has gradually become the centre of African contemporary art. The international Artcurial auction house also recently opened an affiliate here. It’s still only the very beginning, but I think it’s a very good beginning. I think that if you united all of the projects going on here right now on the Marrakesh art scene, including ours, this place could soon become a contemporary art destination in addition to a golf destination.

Vitaly Tsarenkov, Sans-titre, 2014. Mixed media on canvas, 162x114. Courtesy of the Montresso* Art Foundation

I presume that Marrakesh itself has also changed dramatically over these years?

It’s a completely different city than it was before. Just twenty years ago, there were hardly any cars and only a few restaurants in Marrakesh. And that’s not even mentioning hotels. Of course, La Mamounia, which is a classic, but other than that there were perhaps only two or three other good hotels. Today it’s impossible to count them all.

Did you ever meet Yves Saint-Laurent and Pierre Bergé in Marrakesh? Part of their art collection was located here, at the Saint-Laurent residence.

Just a very small part. But no, I never met them. I only know that Saint-Laurent bought a few works of art by artists of the so-called Moroccan school of modernism, which was very strong here in the 1960s and 70s. It grew out of the Casablanca School of Fine Arts (École Supérieure des Beaux-Arts), and among the most illustrious representatives of Moroccan modernism were Mohamed Melehi, Farid Belkahia and Mohammed Chabâa. Especially Belkahia – you probably know his work Aube (Dawn), which abstractly depicts hands.

Saint-Laurent mostly worked here. Back then, Marrakesh wasn’t the party place that it is today. Everybody stayed indoors. The concept of culture in the urban environment appeared here just relatively recently. I remember that the first lounge-type restaurant, Comptoir, opened here in 2003. The next one, Bo&Zin, opened a year later. Up until then there hadn’t been any restaurants of that type here.

It seems that nor was there an art scene in Marrakesh.

Up until 2000, Marrakesh had practically no local art galleries. The only well-known one was from Essaouira. Historically, the strongest art galleries were always in Casablanca, and those were also the first galleries to open affiliates in Marrakesh. Today, there are at least ten very serious art galleries in the city, including Comptoir des Mines and David Bloch. The King of Morocco also loves contemporary art, which is great.

How active is the art collecting scene in Morocco?

There are Moroccan collectors in Marrakesh, of course. And very many collectors from other African countries as well as Europe, the United States and Russia come here as well.

Jonone, Un rêve plus long que la nuit, 2017. © Espace Montresso

Do Moroccan collectors largely buy work by African artists?

African artists are currently in vogue all around the world. And that’s very dangerous. It was the same when street art became a trend about fifteen or twenty years ago – the prices increased immediately, and so did the critical mass. There has to be a process of selection, a sieve for quality. At the moment, there are a great many Africans who want to be artists, and that makes for quite a bit of confusion.

How do you select the artists for the Jardin Rouge residency?

We have two different paths. The first is word of mouth – artists we’ve learned about through friends, etc. Currently, about forty artists apply to the residency every month. They send us their portfolios, and then we make a choice. But I have to admit it’s not easy. If we feel that an artist is especially good, we’ll invite him or her to a first residency, which is for about a month or month and a half. And then we also get a good idea of who this person really is.

Do you ever make mistakes?

Of course. Sometimes an artist will arrive full of conviction that he’ll be able to accomplish what he’s set out to do during the residency, but then it later turns out that he’s unable to finish to project. We usually have about six to eight artists here at any given moment. It’s a mix of people, including already recognised artists and very young artists. We are well aware that it’s very difficult for an artist who’s just starting out to find his or her place in the current art scene. But we have a very good atmosphere here. The fact that we’re located relatively far from the city is also of significance. Because if you’re right in the heart of the city, that urban tension is always there, it’s all around you. Here, on the other hand, it’s like a paradise of sorts.

Jardin Rouge provides the artists with all the basics: a studio, materials, etc. We’ve also had artists returning here several times. Many of them use Jardin Rouge as an opportunity to create something completely new. For example, Tilt, who just had a big retrospective at our gallery. He’s a well-known French graffiti artist who has worked here regularly for five or six years. All of his new projects began here. Or the Russian artist Vitaly Tsarenkov, a.k.a. SY, whose work can be seen here in this room. He has painted quite a few walls in Russia, especially Saint Petersburg.

Returning to African art, do you think its popularity could be enduring?

Art has always had fashions. And the tools we have today, such as Facebook and Instagram, are only accelerating the emergence of those fashions. But of course, that popularity then also fades away just as quickly. I think very many of the African artists who have appeared on the stage right now will naturally be winnowed out.

Carla Busuttil, Sunset Debris, 2020. Courtesy of the Montresso* Art Foundation

How would you describe the African art scene today? How strong is it?

To be honest, it frightens me. Why? The big galleries are playing their game right now. And it’s a game of prices, which are set by the galleries at whatever level they please. And of course, because African art is in fashion right now, all of the galleries are trying to find “their” artist. But there are actually very few African artists with a history of a sustainable, long-term, creative career. And most of them are young. Of course, there are also a few well-known names and experienced artists among them, people who have proved themselves over the long term. However, if you asked me to name a contemporary African artist I believe in, whom I could put my trust in, it would be very difficult. For example, we have Ivorian artist Yeanzi in our residency right now. He was here for the first time two or three years ago. Back then, his works sold for 10,000 to 20,000 euros on average, but now their auction prices have grown to 40,000. And it’s not really clear why. It’s difficult to understand. It’s always complicated to calculate the price for an artist’s work.

But, returning to the Jardin Rouge concept – we’re more interested in helping an artist to experiment. Maybe experiment within his existing style, but, for example, with different materials. Such as American graffiti artist JonOne, who is now already quite well known on the international art scene. When he visited us the first time, he worked only with oil paints, not acrylic. This challenge to do something new is essential for every artist. And it’s interesting. But if we’re talking about subsequent prices for this work, to be honest, that doesn’t interest me any more.

But, when you organise an exhibition of this or that artist’s work, you are in effect also operating as a gallery.

We operate as a gallery, but we do not organise classic exhibitions. For example, the Tilt show I mentioned before is actually more like a retrospective. It covers the past five years of his career and shows how he has developed in order to arrive at this particular result and where he might be headed in the future. His newest works basically already point in that direction. I think in the future Tilt will return to his graffiti roots; he’ll paint another wall. Because it was precisely as a street artist that he gained recognition, even though he currently works in a slightly different direction. So you can’t really look at this as a truly commercial exhibition. Tilt, for example, is represented by several different galleries, and we’re not interested in competing with them. For us, it’s important to show some completely different work by him.

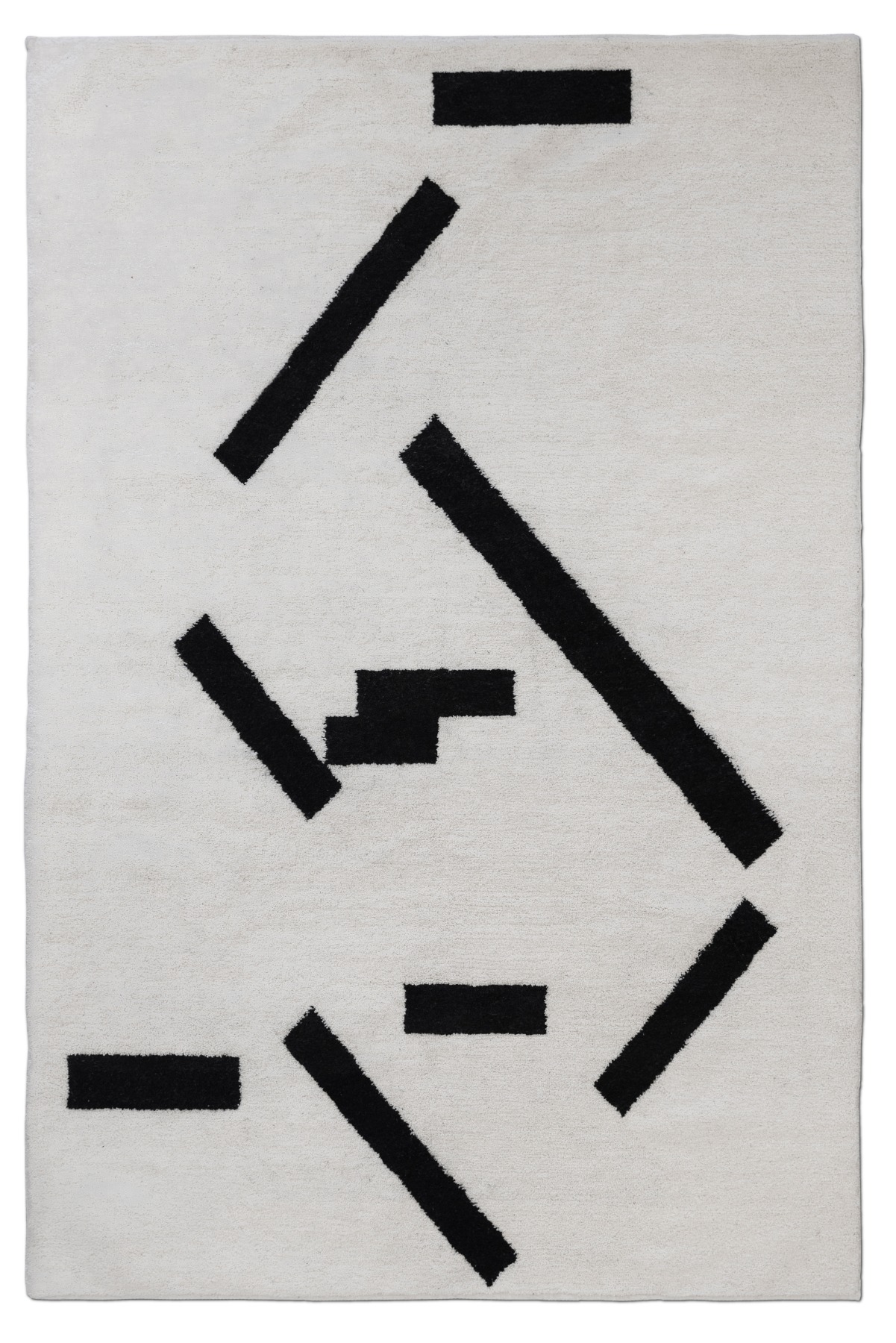

Or Tania Mouraud, who’s a global star right now. She wanted to try her hand at the textile genre, and so she wove carpets in the traditional style together with some Berber women. This was also interesting for us, because just putting on another classic Tania Mouraud show – the kind that has been seen at the Centre Pompidou in Paris, MoMA in New York and many other places – isn’t very exciting. But here, she tried doing something completely different and was very pleased with the result herself.

Tania Mouraud, Grillon, 2019. 405x250cm. Courtesy of the Montresso* Art Foundation

How would you describe your private collection? Is it based on street art as well?

As for many collectors, the beginning was quite chaotic. I bought everything. I’m from the South of France, and in my youth, up until the age of thirty or so, I was very into the so-called Provence school, the École de Nice: Arman, César, Dufrêne, Hains, Klein, Ben, etc. I acquired quite a few works of art by representatives of this school, including Arman and César, whom I also met in the 1970s. I’ve always been particularly fond of Ben, and one of my all-time favourites in my collection is a painting of his that I bought in 1969.

Later, of course, a large part of my collection has consisted of work by artists whom we’ve supported. I also have a lot of work by Russian artists in my collection.

Has it always been important for you to form a relationship with the artist, to meet him or her?

Ever since I started collecting, I’ve been linked with people from the art world. In my youth I even met Picasso once. To be honest, though, I was not at all the main actor in this meeting; I was more like a shadow, but I was nevertheless in Picasso’s studio. And if you’ve had the opportunity to meet a person of that stature – a monster, to be precise, because Picasso was a monster in real life – it’s naturally an unforgettable experience.

What happened at the meeting?

It was in Aix-en-Provence. In my youth, I had a very close relationship with the French poet René Char, and there were a lot of artists in his circle of friends: Kandinsky, Picasso, Braque, Matisse... I also spent a lot of time at the Fondation Maeght. In a way, that was my school. The first time I went there, I didn’t understand art like that at all. But now I understand it.

What do you remember about the meeting with Picasso? What was he like?

Actually, it was René Char who was meeting Picasso. Picasso had lived in Aix-en-Provence for three years already. Char’s chauffeur was a good friend of mine, and I simply saw Char speaking with Picasso. Even though I was some distance away, it’s impossible to describe the energy and charisma that surrounded Picasso. He was a bold, reckless person. Not just his art, but he himself. His whole essence. You could physically feel it, like a vibration. We were in his studio, which actually wasn’t like a studio – there were paintings all around, it was a crazy mess. And he himself in the middle of it all. I still remember it very well.

What does art mean to you? What do you look for in art? Do you look for aesthetic enjoyment or intellectual challenge?

I don’t like conceptual art. If I look at a work of conceptual art, I first need to understand it. But that doesn’t always happen. So I very much like to talk with the artists. If the artist’s idea is clear to you, then that’s the first step on the way to understanding a work of art. Second, art must always be aesthetic. I don’t like artists who pay no attention to aesthetics. I’ve noticed that up to a certain point conceptual art has a flow of truth to it, but then it usually turns into a rationally calculated manipulation of the spirit of the times, and that frightens me. So, I’m quite cautious when it comes to contemporary conceptual art. But once in a while I do like something, and then I share my thoughts about it with other people in the art world and receive an answer along the lines of “Ahh, great that you like it, but it’s complete shit...” That has happened, too.

I like artists who make truthful work. Even if they’re conceptual.

TILT, Future Primitive, 2019. Courtesy of the Montresso* Art Foundation

Where did your passion for bright colours begin?

Maybe because I have poor eyesight. I’m not colour blind, but I’ve always been fascinated by bright colours. As you can see, I have them here as well. It’s possible that my time in Russia has also had an influence. There’s almost no sun there for four months out of the year. That’s why you find big windows everywhere in Russia, even though it’s such a cold country. Because there’s so little sun. In Morocco, on the other hand, there’s lots and lots of sun and small windows everywhere. My eyes demand that art be bright.

What do you think is the role of art in today’s society as a whole? How strong is its voice, also in terms of current social, political and ecological events?

If we look over the past century, one hundred years ago art played a very large role in politics. But today it seems to me that those two spheres are on parallel roads that do not intersect.

Why is that?

Art had a strong voice during the revolutions of the 20th century, both in Russia and in South America. Very many people gathered on Red Square, but when Lenin began speaking, who could hear what he said? Maybe those in the first, second, third row? But all of his words were written on the walls. Artists also drew on the walls during the Mexican Revolution – they drew about how the army was killing farmers and so on. They used art for revolution.

Today, art is iPhones and Instagram. The communication system is different today. Art plays a role, but its playground is mainly just the art world. Interestingly, art also played almost no role during the Perestroika era. I honestly don’t see where art and politics might intersect today. Perhaps the last place in the world where it still happens is in China. Today, it’s Facebook that’s a political player, not art. Yes, you can list a few examples where artists make use of politics, but not the other way around, with politics making use of art. For example, there are very large strikes in France right now, but artists play no part in them whatsoever. In the past, artists were very vocal about social issues, but I don’t feel that anymore today.

The last remaining country we should try to take a look at and discover is North Korea. I haven’t been there, but there was an exhibition of North Korean art in Moscow. Very interesting. They have a very good school of art there.

At the same time, more and more artists are addressing climate change and the environmental crisis in their work.

Yes. But are they artists who use their talent to speak about ecological issues and saving the planet, or are they artists who use ecology as a marketing tool for their art? It’s like what we already talked about in relation to African artists. Right now, Africa is in vogue. Ecology is also in vogue. It’s the same as the story about the chicken and the egg. Which came first?

TATE, Novembre, 2019. Courtesy of the Montresso* Art Foundation

From the perspective of art, can the continent of Africa now be considered as fully discovered?

Yes. And the saddest thing is that Africa has such strong cultural traditions of its own, but so many contemporary African artists try to work like European artists. They copy the European style.

Galleries definitely play a role in this process as well.

The professional gallery scene has changed very much. Today there are very few galleries like those in the past, which truly helped artists. Well-known gallery owners today operate to strengthen their own names – they work for themselves, not for the artists. There are very many artists in the galleries today who have a one-off success and then are forgotten. In the past, a gallery would help a single artist for fifteen years. And the gallery would really help the artist. Today’s gallery owners are more like sellers instead of classic gallerists.

It’s the same with art foundations. For example, the Fondation Louis Vuitton. It does very interesting things, but if we compare it with the Fondation Maeght fifty years ago, it’s a completely different kind of work. Louis Vuitton today is playing the market with art, and the price of a work of art is at the top of the list of values. When Aimé Maeght established the Fondation Maeght in the 1960s, he wanted to help artists. He gave them the opportunity to realise their ideas. It was a completely different profession back then. There are hardly any galleries today that help artists in this way. Undoubtedly, gallerists help artists increase the prices for their artwork, because as soon as a gallery like Gagosian, for example, shows interest in an artist, everyone immediately wakes up, because they know the prices will increase.

You could say that, in a way, we are today doing a part of the work that galleries used to do. We help artists and give them the opportunity to realise a variety of ideas.

I must say, though, that the Fondation Maeght has also changed along with the times and the new generation.

Of course, it’s no longer what it once was, when the grandfather was still alive. Today, it’s a venue for exhibitions.

Do you think that the situation in the art market could change in the coming decade? It seems to currently have reached a certain apex, and Gagosian is not so young anymore either. Back in the day, Leo Castelli set in motion the paradigm shift in the art market that laid the foundation for the current “shark show” put on by the big galleries.

It’ll be his son. Well alright, Gagosian doesn’t have a son...so it’ll be the “Gagosian school”... Right now, wherever you have talent, there you immediately have marketing. And it’s quite ridiculous in a way. I recently visited a fellow art collector and saw a very good painting on his wall. I asked him who the artist was, and you know what he said? That he simply didn’t know. I asked his wife, and she didn’t know, either. The only thing he knew was that he had bought it at Gagosian. And that it was truly a very good artist, a very good work of art...but, unfortunately, he couldn’t for the life of him remember the artist’s last name. That happens very often. Nowadays at exhibition openings, people turn their backs to the paintings and just drink the champagne. Galleries, museums – they’re the fashionable venues of today. As you know, Andy Warhol’s greatest dream was that everyone could buy a work of art for their home. In his defense, though, he never imagined that his silkscreens would one day sell for millions. That wasn’t his intent. He wanted to create works of art that were available to everyone.

TILT, Future Primitive, 2019. Courtesy of the Montresso* Art Foundation

Returning to Jardin Rouge. You designed the building and also the furniture here.

Yes, architecture is my hobby. I’m bad at art myself (laughs) – I have lots of ideas, but I have trouble realising them. But I love architecture, and that’s why I experimented here.

Have you also studied architecture?

No, it’s just a hobby. And here I realise my architectural fantasies.

But you must have realised those fantasies together with a team of architects?

No, all by myself. If I had invited a team of architects, the situation would have noticeably become much more difficult (laughs). Right now, we’re planning a building to display the foundation’s collection through rotating exhibitions. We’ll start working on the project this year.

What were your main guidelines when you created the current gallery space? What did it have to look like?

I promised one of our artists that we’d organise an exhibition of his photography. He said good that we wanted to organise a show, but that we didn’t have a space where to do it. I said that’s alright, I’ll build one! And six months later we had built this building to house his exhibition. We now host four shows a year here.

Jardin Rouge, 2020. © Cyril Boixel

Collectors come here from all around the world. How do you think collectors and their approach to collecting have changed over the past ten years?

There are still collectors who love art, and that’s very good. Of course, there are also collectors who come here, look around and say, “Wow, this is a well-known artist, I know him, the price for his work has doubled in the past three years...” These people know all about prices, but they know nothing about art and artists. But there are also collectors who come here two and three times a year and are truly interested in artists. And just like me, they love talking with artists. And I’ve noticed that as soon as they start talking with artists, they always buy something. That’s very important. At the closing of a residency, we always organise an exhibition that the artist also attends. The artists play a crucial role in this process, and they tell the visitors why they’ve done this and that and not something else. In all, there are about 200 to 250 collectors who come here regularly and show continued interest in our work.

The new galleries no longer have this relationship between the artist and the collector. Instead, it’s a relationship between the gallerist and the collector. And separately – between the gallerist and the artist. Unfortunately these paths do not cross.

Does the foundation’s collection include art by all of the artists who have participated in the Jardin Rouge residency?

Yes, all who have accomplished a minimum result are represented in the foundation’s collection. If an artist has been here more than once, we have a work of art from each of his or her residencies here. I don’t even know how big the collection is. It could be somewhere around 1500 works of art.

Jardin Rouge, 2020. © Cyril Boixel

Do you still add artwork to your personal collection?

Like many collectors, my collection is located “inside the box”. I have a house in central Marrakesh where, of course, I display a variety of artwork, but most of the collection is in storage. That’s why it’s so important to build this building that will also have room for my own collection, because the art represented in my collection will show how we have arrived at the Jardin Rouge project today.

I hope there will always be a residency programme here that will help artists. But of course, I don’t know what will happen after I’m gone. That’s always a complicated question. As we were saying about Gagosian, what will come after him? There will be other Gagosians...

Some collectors believe that a collection is so closely linked to its founder’s identity that when the founder dies, so does the collection.

I think all collectors think about this issue. Of course, I could continue buying work by a variety of artists, but I’ve also come to the point where I have to ask myself why. What’s it all for? What we’re doing now is much more interesting. Because with Jardin Rouge we have this constant link with artists, and that’s the best thing that can happen. Of course, sometimes that relationship can be difficult or painful. But no matter whether it’s difficult or easy and gentle, any connection is interesting.

On the walls of my apartment in Paris, too, I have only artwork by artists with whom I’ve had some kind of contact, some kind of link. Not one work of art there is by an artist whom I have not personally known. And that’s very pleasant, because each piece is not only a work of art but also a moment of my life.