I am sort of 100 percent a book person

An interview with Bernard Shapero, dealer of rare books and founder of Shapero Rare Books

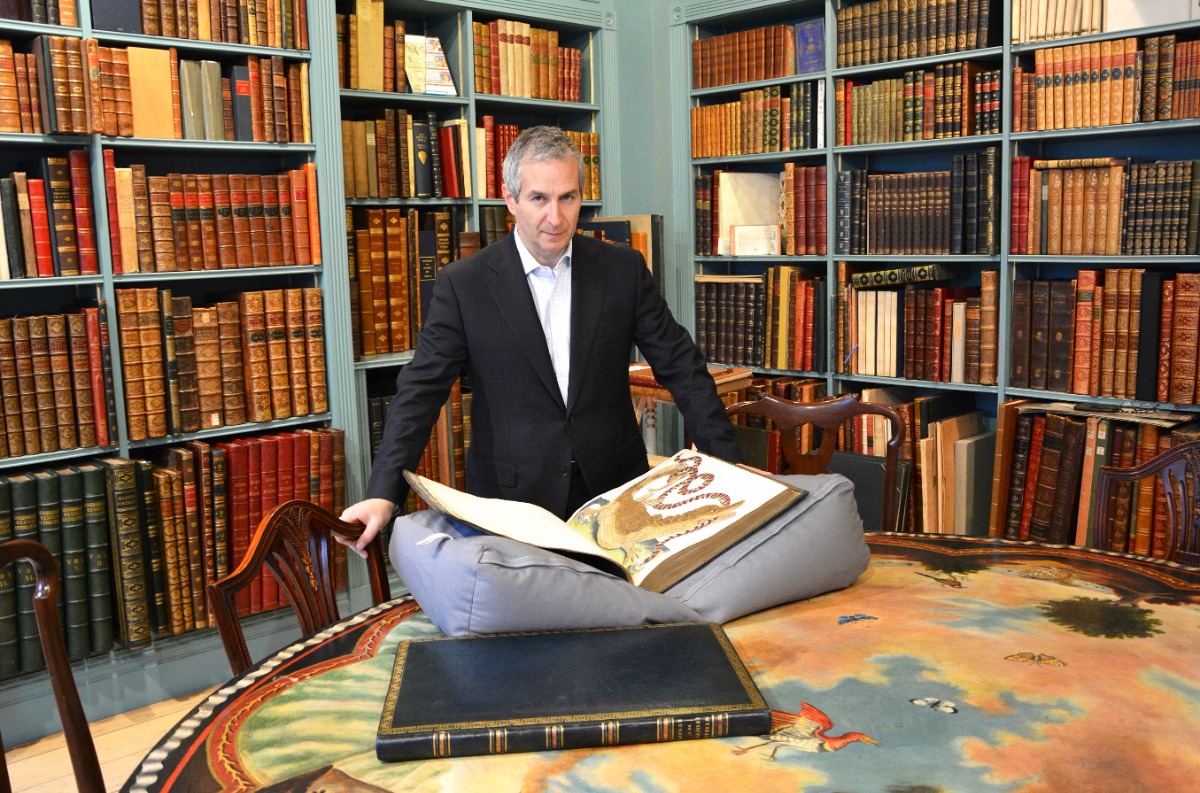

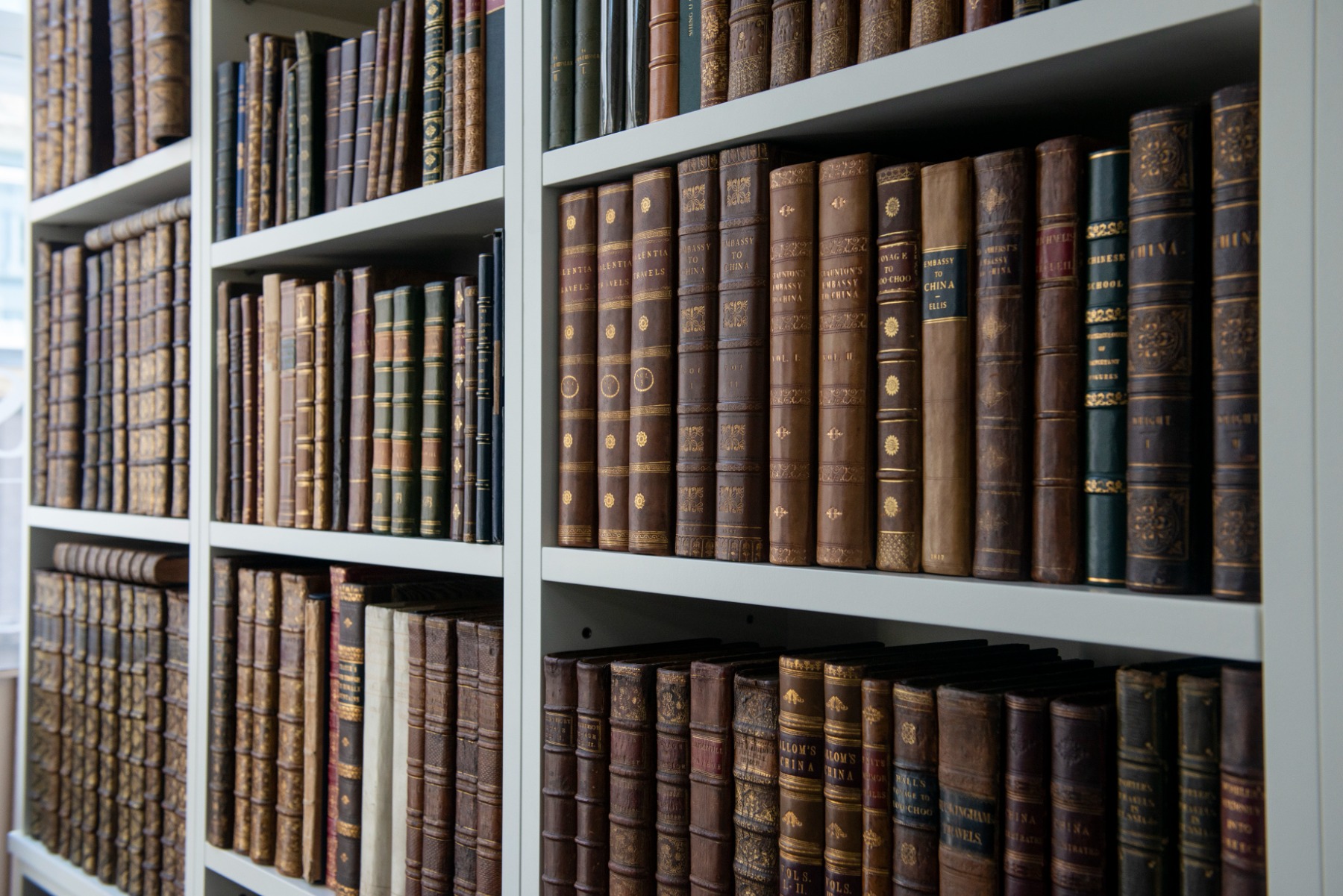

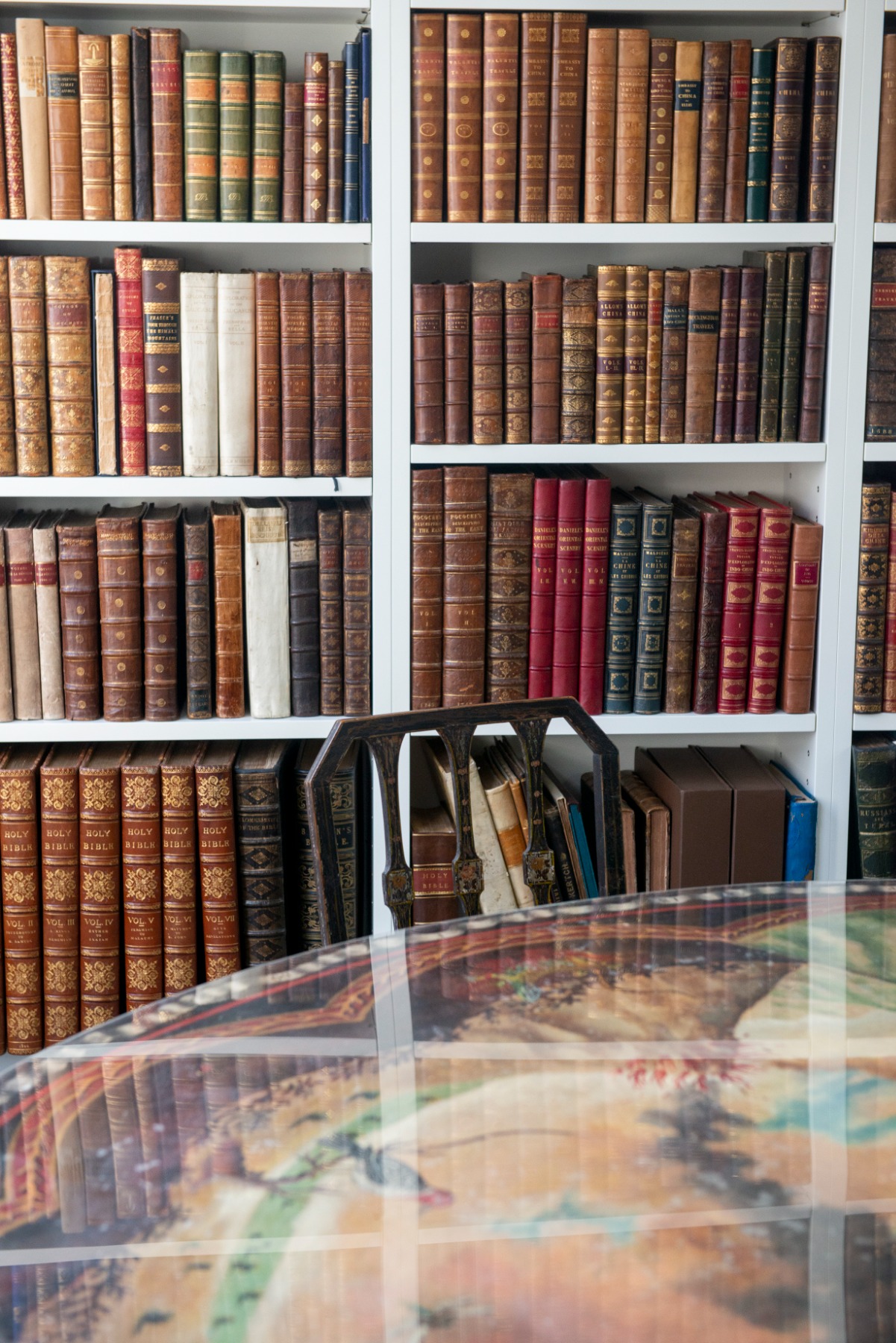

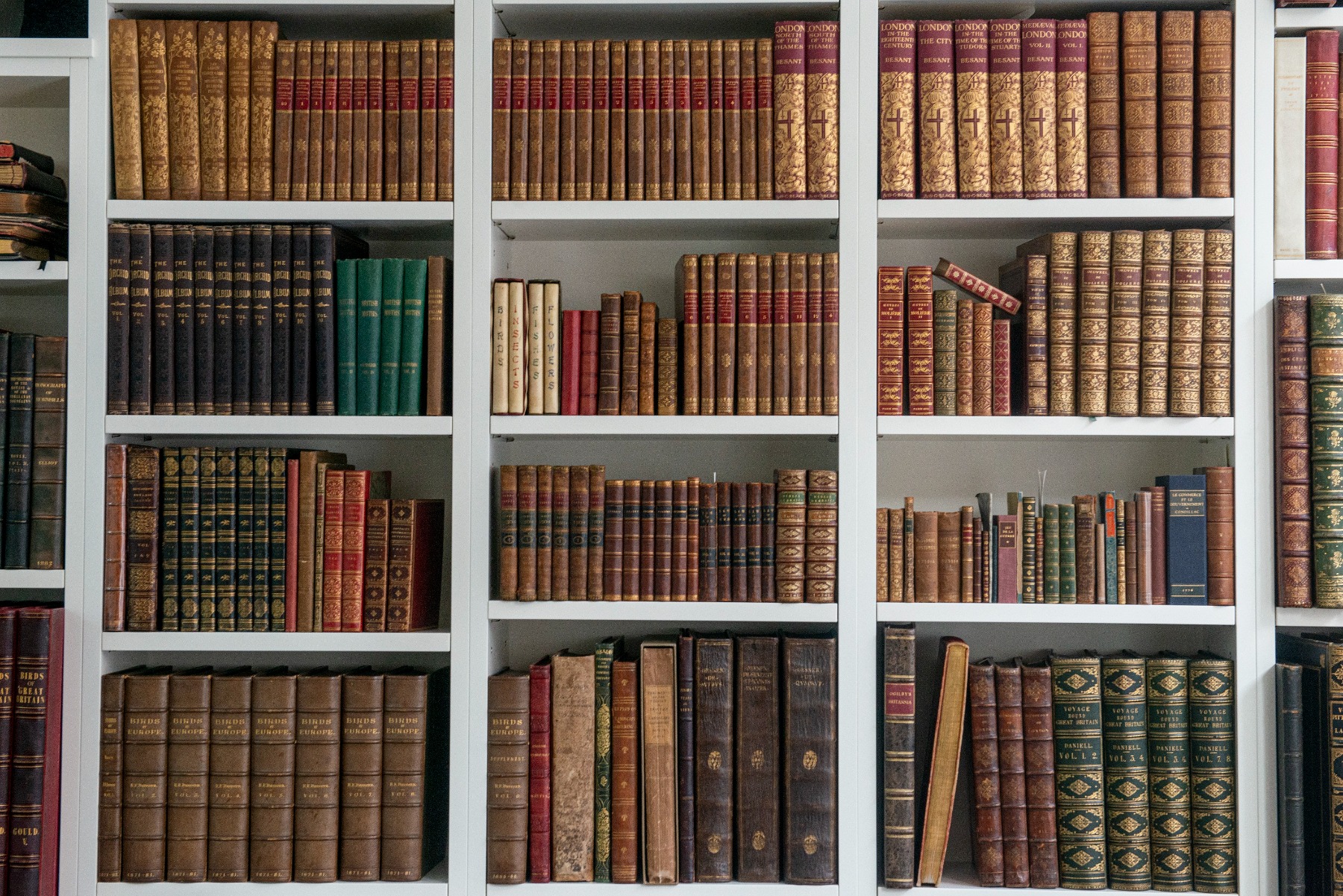

Bernard Shapero is one of the best-known and respected dealers in the world of rare books and the people who collect them. An interest in history and the artefacts that embody its twists and turns is in his genes, so to say. Shapero’s father was a collector of armour and gold coins, and Bernard himself began dealing in rare books in the late 70s, when he was still a pupil at Highgate School, just thirteen years old. Shapero started off buying and selling 19th-century Baedeker travel guides, and as soon as he finished school he opened a stall at Grays Antique Market. By 1989 the enterprise had developed into a gallery/shop in Holland Park, but since 1996 Shapero Rare Books has called London’s Mayfair district home. It is a true treasure trove for those interested in fine illustrated books from the 15th to the 20th century, travel and voyages, natural history, literature (including modern first editions), children's books, guide books, and more. Slate magazine has described Shapero Rare Books as ‘a Taj Mahal of rare books’.

In 2014 the world of Shapero Rare Books was joined by Shapero Modern, which specialises in postwar and contemporary prints, multiples, and works on paper with a particular focus on American 20th-century art. Having at first been located in the same building as Shapero Rare Books, in January Shapero Modern will have moved to a new place on Maddox Street. The new space will symbolically open its doors with What You See is What You See (28 January – 20 March 2021), an exhibition featuring the work of American artist Frank Stella; it will be the first comprehensive UK exhibition of Frank Stella’s works since 2013. The exhibition covers the period 1967 – 2001, showing the progression of Stella’s prolific career. The Shapero Modern show is a survey of Frank Stella’s prints and works on paper bringing the experimentation in his printmaking, his love of colour, and his enduring relationship with abstraction to a new audience.

Our conversation with Bernard Shapero took place over Zoom, and although he did not hesitate from insisting that ‘we will get back to how we were, 100 percent – or at least 98/99 percent’ by 2022 or 2023 at the latest, he did concede that digital technologies are a measure that is here to stay in the world of rare books.

It appears that you’ve never had a problem with the existential question of ‘Who am I?’, as you’ve often been heard to say that you are ‘100% a book person.’ What is it like being a ‘100% book person’ in the second decade of the 21st century?

Well, I am sort of 100% a book person, but there are other facets to me as well. I mean, I'm obviously very committed to selling, buying, dealing and, you know, curating anything to do in the rare book world. I've been involved in it for 41 years. So in that sense, I'm totally committed to it. The 21st century, I think, is exactly the same as it's been for the last 600 years, but completely different from how it's been in the last 600 years. We buy, we sell, we trade, we meet collectors, we meet with libraries – as it has always been – but now we just use different methods for doing the business. You know, with the Internet, the emails, etc. That's a whole new world which didn't exist 20 years ago. But the principles are exactly the same.

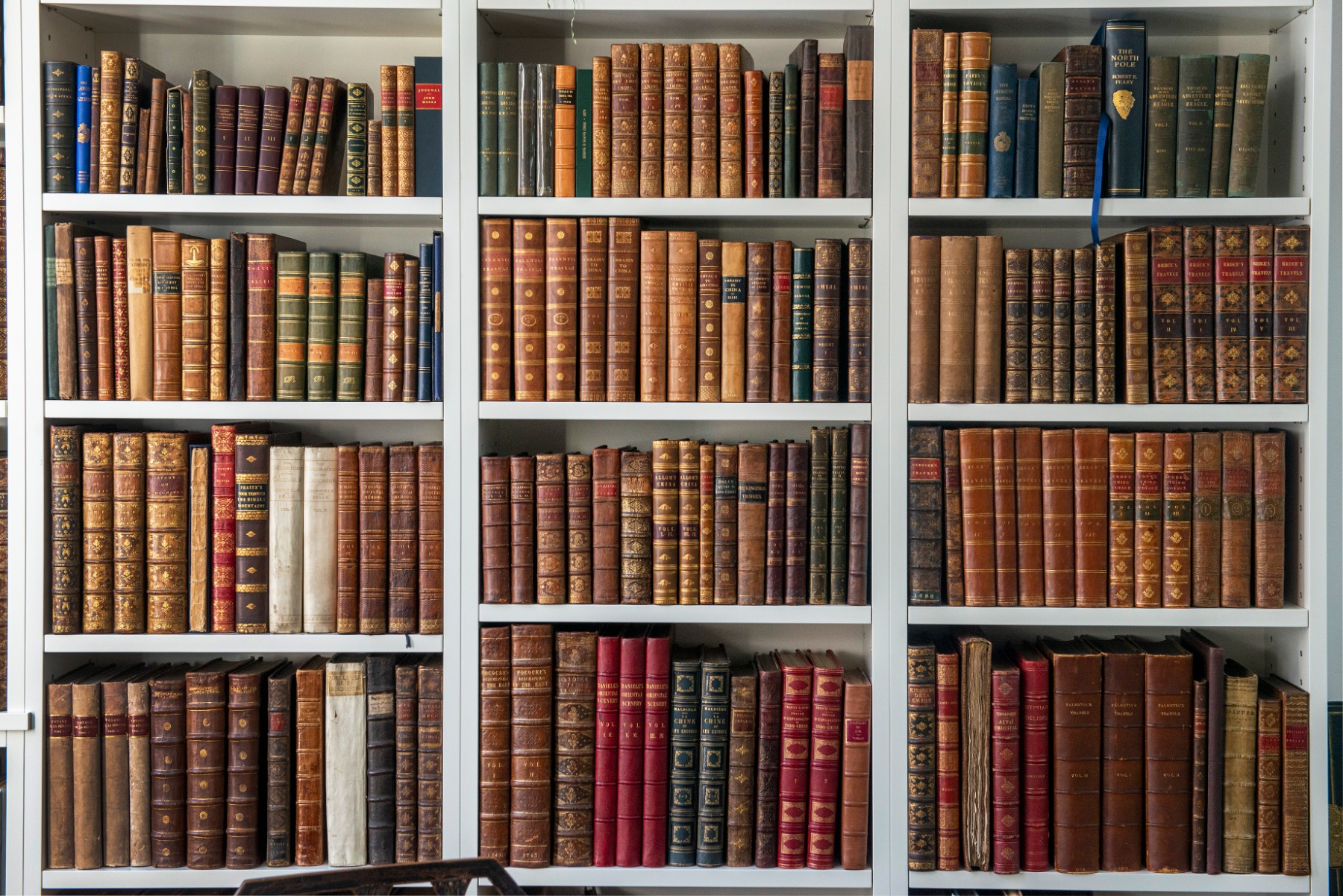

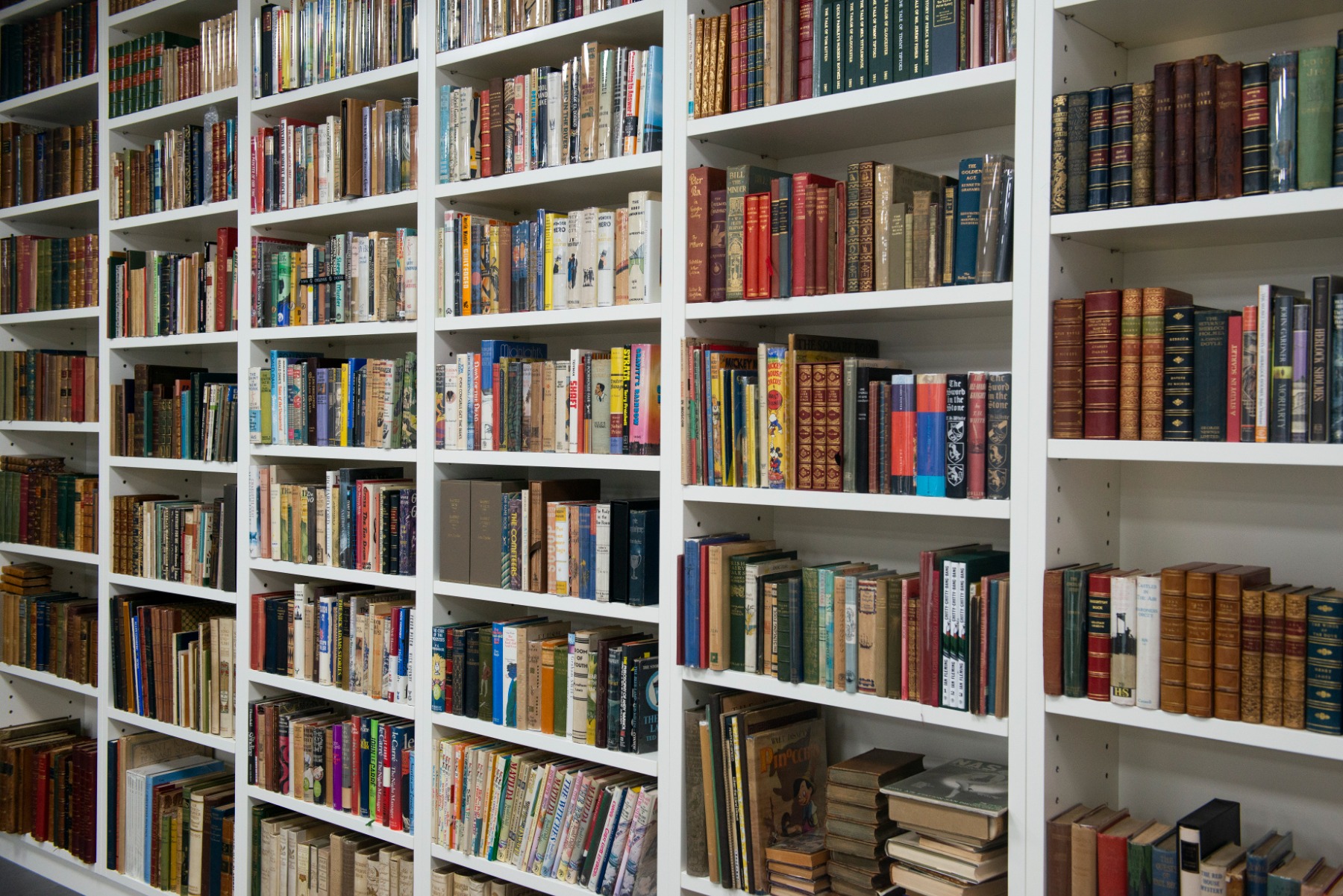

Shapero Rare Books, New Bond Street

The world in general has changed, and is continuing to do so. What do you think – has the place of books in people's lives changed as well?

Well, I think in general, books are getting rewards. Books have clearly had a good boom in the Covid-19 era. People are spending much more time at home. They've got a lot less time to do other things. They don't go to the theatre, they don't go to the cinema. They don't go to football matches. They don't go to the opera. They don't do anything. I mean, they go to work, if they do, and then they come home or they are at home and they are working from home. So they have a lot more time to be at home and read, if that's what they like – more time than they've possibly ever had in their lives. So that's good for the book business in its little way. I mean, we're not like a television or something. But in our own way, the Covid lockdown has been good for the book business.

I’ve had the opportunity to meet and talk to quite a few contemporary art collectors. What is the main difference between an art collector and a book collector (if there is any at all)? And how many serious rare book collectors are there in the world? I assume the number is smaller than that of contemporary art collectors. You once said that if ten people in the world want a particular book, that's a huge amount of demand, but if there are 20 copies of a book on the market, that's a large supply.

We're obviously a small, much smaller, community than the contemporary art world. Collecting is an illness that all dealers want people to catch. There's no vaccine. There would never be a vaccine for collecting. It would be a disaster. So we are very keen for people to get ill with collecting, whether it's contemporary art or rare books or snuff boxes. It's all the same. The difference for books is that one has a library and one may collect hundreds and hundreds of books in one’s library.

I know there are contemporary art collectors who have far more art than they own houses or walls to hang them on, and they end up storing it in a warehouse. They may buy pictures they never see.

The beauty of collecting rare books is that you have your own library, and it's very, very rare that a collector will not have his books around him. So, collectors of rare books like to have their objects around them. I think that's the difference with collecting contemporary art. You know, once your house is full, some of the appetite can diminish a bit. Obviously, one could say once your library is full, your appetite can diminish. But I think with books, people tend to keep going. The books are known to take over houses. But again, art is also known to take over people's houses. I'm sure we've all seen crazy art collectors who have got art everywhere. But I think it is a little bit of a more normal thing to have books in your library, in your bedroom, in your your living room. But, I mean, generally it is the same – collectors are collectors, whatever it may be that they’re collecting.

Obviously, collecting art that goes onto walls is very public. Most art collectors want to buy things that they can share with their friends: Oh, I've got a Picasso on the wall. I've got this new artist from America or wherever. And people will go and say: Oh, you got that artist... Yet with rare books – and with a lot of the collectible world, like stamps or coins – this sort of stuff is very personal. You can come into a library and there could be one hundred million pounds worth of books, but you would have absolutely no clue to that being the case. So, these collections are not ostentatious.

With contemporary art particularly, but not always, one has the feeling that a lot of collectors are buying not just for themselves but for showing it to other people. For rare books, that generally is not the case.

In his brilliant essay devoted to book collecting, Unpacking my Library, Walter Benjamin noted that ‘the collector's passion borders on the chaos of memories.’ How would you characterise collectors of rare books?

There are probably thousands of book collectors in the world, but on the highest end there are only, you know, a hundred or so. I don't know the exact numbers, but you're talking about maybe just ten percent of the number that collect contemporary art. So, it's not near as big a market as contemporary art.

Everything in the world has it's own fate and it's own story. As do rare books. How important is the provenance and history of a book – both for you as a dealer and for the individual collector?

Sometimes it can be quite mundane and of no particular interest, and sometimes it can be incredibly exciting and amazing, adding huge value to the book by making it far more interesting and important.

Shapero Rare Books, New Bond Street

Is there a fashion involved in the buying of rare books – any literary ‘trends’? I’ve heard that James Joyce first editions have experienced a boom in recent years, for example.

I think it's not so much the literature, per se. I mean, yeah, there are literary trends and trends in all areas of the book collecting world. At the moment, the trend for scientific books is very strong due to ‘tech company people’ – you know, the people who are involved in tech often have a scientific background, and so they like scientific books. It used to be that finance books were very strong because the people from the financial world were so important. Rare books sort of flow where the money is. So, in the tech world they want scientific books, whereas in the financial world they like books on finance. You know, if the cleverest and richest people in the world were suddenly architects for some reason, then I'm sure architecture books would boom to correlate against that.

So that's sort of quite an interesting thing. Again, that doesn't really work so much in art. I mean, you might say that there's a great appreciation of African-American artists at the moment, and with the hashtag Black Lives Matter it might just make for a sort of boom in that area. But the beauty of the rare book world is that we encompass actually every subject area. You know, we've got beautiful books on contemporary art. We've got people books on science, on medicine. We've got people books on travel. The environment is a very big issue at the moment in people’s lives, and there are beautiful books on the subject. That is one of our great things – whatever your interest, whatever is going on, whatever you want, we can provide you with beautiful books on it. We are unique.

I understand that there’s always been a huge interest in books on natural history. What makes them so special throughout the times?

Well, the main thing about those books is that they're beautifully illustrated. So they're amazing things to look at. They are works of art in their own right; they transcend the book world and become works of art, which is why there has always been such a high value associated with them.

Are there frauds also in the world of rare books? Is it easier to check the authenticity of a rare book compared to that of a painting?

I would say that 99 percent of all rare books are easily identifiable as being original. As prices go up, there are now cases of people faking certain types of books. Clearly it's quite expensive to fake things sometimes, and quite difficult to fake an old book. So it's very, very rare. But there are certainly incidences of it happening. That’s why it’s important to work with a qualified dealer such as ourselves – you're relying upon us to weed those things out to make sure that you're protected from that sort of situation.

Where is the biggest market for rare books at the moment? I heard that not so long ago it was Russia, and also China.

Yeah, Russia has been a great market for us, particularly because the Russians love books. You know, they're great book buyers and they always have been. In Russia, books signify a genuine intelligence and are culturally held in very high esteem. Unfortunately, the world has suddenly shifted, and for obvious reasons Russia is a problematic market at the moment.

China was a huge market up to a year or two ago, but again, it did cause problems with their currency and their exchanges and their tight regulations. The biggest market, as usual, is America.

Shapero Rare Books, New Bond Street

In 2016 you were involved in the selling of four precious fragments of the Dead Sea Scrolls. What is the most special book you have bought/sold during your career?

In 2006 we bought at Sotheby's the first-ever printed atlas. Published in 1473, and also known as the Cosmographia or Geographia, it contained 26 double-page engraved maps by Tadeo Crivelli. We bought it for three million pounds, and this was probably the most expensive printed book sold outside of William Shakespeare’s First Folio and Birds of America by James Audubon.

So I would say that buying this, the most important and earliest printed atlas – and which has only one other copy known in private hands, was one of the highlights of our career. So that was very exciting.

But we've delved into all sorts of different things. For instance, we bought an amazing collection of 300 incunable books printed between Gutenberg (circa 1455) and 1499. We’ve bought early Bibles: the most fantastic copy of the first Bible ever dated, which was 1461 – the first Bible after Gutenberg. That was a magnificent book. We've had some fantastic buys over the years. We had a complete set of the works of John Gould, one of the most distinguished ornithologists of the nineteenth century, and also a brilliant artist and highly skilled publisher.

So we have dealt in a quite wide range of books from the 15th century to the 20th century.

Could you describe the process involved in finding these books? Covid-19 has currently restricted travelling, but I assume that it was once a large part of your life.

I travelled extensively, like everyone else. We were running around the world the whole time, searching for books, buying, selling, talking, meeting collectors, discussing collections. The lack of travel now is a real problem, certainly in my view, for the whole industry. Everything is online now, but it makes life a lot more difficult. I mean, ‘online’ is a double-edged sword, you know. Obviously it's got some great points, but it's also got some bad ones.

Do you think that when the pandemic ends (hopefully it will, at some point), the world will return to the state it was in before, or will some changes be permanent?

I think that obviously the Internet and ‘online’ is here forever, there's no doubt about that. But I do think that generally things will go back to how they were, maybe not by 2021, but by 2022 or 2023. Basically, at the end of the day, we will get back to how we were, 100 percent – or at least 98/99 percent.

I don't think that it will change things – a year or a year and a half of this pandemic, in the scheme of life, is nothing, isn't it? We hopefully all have, let's say, 80 years – if during one year of that there's been an issue, it's not a big deal. We'll forget about it, look it over, and we'll move on.

There will obviously be some changes to do with ‘the online’ and, you know, Zoom, etc. But I don't think there’s going to be any fundamental change – for example, that we're never going to out again, and it's the end of theatre, the end of opera. I mean, it's ridiculous. I think as soon as people can get back to normal life, there will be a rushing back to it. Everyone wants to get back to normal. Everyone wants to go to an art fair again. Everybody wants to go to the cinema, the opera, the theatre or a football match or whatever it may be that they like. We all want to get back, you know, so we'll definitely get that.

We will do the bidding online at auctions; we will be reading catalogues online. There will be less printing. Maybe that's a change. But these are small, little things in our lives. You know, we're animals of that type. Nothing will change. It's just a little bit of time and we'll be back to 98, 99 percent of where we were a year ago.

Shapero Rare Books, New Bond Street

But what about the physical book in relation to technology? A few years ago, people speculated that bookshops were going to die out and that Kindle and e-books would soon take over. Do you think that there is a possibility that one day books will die out?

Books could die out in time. I would say that is possible. But look at the record industry now – they didn't really make records anymore for a while. Yet the market for collecting records is very strong. We don't use gold coins anymore, do we? But people still collect gold coins. So, what does that mean? Do people still buy Superman magazines? No, they don't exist anymore, yet people still collect them.

I don't think that there is a death of the rare book. Well, who knows what might happen in a hundred years, but I wouldn't doubt very much that you, I, or our children – or even our grandchildren, if we have them – will still be around books. After that, I can't tell you.

How would you characterise the feeling you get when you take a rare book in your hands for the first time? How do you approach it – must you wear gloves?

No. I mean, except for some very modern books, especially art books, when sometimes you might want to wear gloves because you don't want to get any dirt on the paper at all. But for any old book you don't need to wear gloves, no. That's a fallacy. If you're in the normal course of having clean hands and being a normal person, you don't need to wear gloves at all.

What goes through your mind when you’ve finally acquired a book that you’ve been hunting for months, or even years?

Depends on how much I've paid for it. If I paid too much, my feelings are: Shit...I payed too much... But if I got it very cheap, I'm very excited that I bought a tremendous bargain. I mean, in the rare book world, occasionally you might get a book that's really exciting, something really special. But, you know, after 40 years of dealing with things, you might see one of these books once every ‘whenever’ – two years, three years, five years. I mean, it's rare.

You know, we are business people. All of the art world – they are business people. Larry Gagosian is a businessman. Of course, he loves art and I love books. But he's a businessman, and art dealers are art dealers; they are not artists that make the art. They sell the art.

Of course, every once in a while you find something where you say: Wow, this is really spectacular, very special. And sometimes it doesn't have to be super valuable – it can just be really interesting.

Once I bought a beautiful little book that was quite valuable but not hugely valuable. It was a manuscript made for Louis XVI, the king of France, who later presented it to Marie Antoinette, and it had been in her bed chamber. What a fabulous history of a book! I mean, that's a nice thing – you feel that you are holding a real piece of history in your hands. So there are occasions like that, when the book gives you a bit of a warm feeling.

Shapero Rare Books, New Bond Street

Is a book a work of art, or is it more of an object?

It can be a work of art, occasionally. Not always. For example, if it has a very beautiful binding or inside is a manuscript of some sort, or if it has beautiful illustrations. We talked about bird books or flower books, or beautifully illustrated books by artists throughout the last 500 years. A book illustrated by Dürer is a sort of a piece of art, as is a book illustrated by Picasso or Chagall, or by some contemporary artist.

In the beginning of our conversation you compared collecting to a virus. How easy or difficult is it to catch this virus? Is it already in one’s genes? Or perhaps one can catch it like a cold, but not quite as often.

Most people are born with it, you know; thankfully, they don't have any chance to get rid of it. You'll find that a lot of collectors collected some sort of weird stuff at school. I collected milk bottle tops at school. I collected pink stones that I found on the beach. And that's how it begins, and obviously, the more money the collector has, the bigger the collection gets.

And then there are people who have sort of become more educated or financially better off, and so they feel they want to do something with their education and their money, and they say, well, I want to start collecting. But those people tend to be more modest collectors – not always, but they tend to be.

The most serious collectors, in my experience – if you scratch the surface, you find that they were collecting something as children, and then it's just grown.

In January you will be launching Maddox Street Gallery, a new space for Shapero Modern, with the first comprehensive UK exhibition of Frank Stella’s works since 2013. Could you say a bit more about that?

My interest is so very wide-ranging. I'm not a specialist per se, and my curiosity is very broad. So I tend to move about a bit. I've always really loved postwar American art. And in terms of this gallery, we saw it as an opportunity to be one of the very few dealers in England dealing postwar contemporary art. We wanted to have our own niche, and that seemed like a lovely area to go into. And so we've exploited that and we've built up a business based around that as a core. Frank Stella is one of the great American artists that we follow and like.

Returning to books. Are you an avid reader yourself? What kind of books do you prefer?

I read all day, every day, mainly about books or catalogues. What I'm an avid reader of is magazines and newspapers. I'm very keen on current affairs and history. But most of the time I'm reading catalogues and scrolling through thousands of catalogues online and in hard copy – all day, every day.

Shapero Rare Books, New Bond Street

Have you ever experienced a moment in life when you feel as if you are living the life of a character in a book?

Am I living the life of a character in a book? No, I don't have any character quite like me in a book. I don't know if you know the TV comedy programme ‘Black Books’. The series is set in the eponymous London bookshop and follows the life of its owner. His name is Bernard, and Bernard is quite an unusual name. And the man who plays him, the lead character, is quite young. The man who wrote the show, I believe, lived quite near to where I used to have a bookshop. I'm not sure, and I would actually love to find out in reality, but I do believe that I was vaguely in his mind when he wrote this. Because I had a bit of an eclectic shop like the one in the show, and I am called Bernard. I don't know whether that's true or not, but I like to sort of pretend it's true.

I think I'm sort of very typical of many dealers, but I'm very different from many dealers as well, at the same time. You know, all dealers have certain traits that are very similar. And then we've all walked our own individual style. In a way, like every group of people, we're all very similar in one sense, and yet we're all very different in another.

But what is this difference – could you characterise it?

Between me and other dealers? Well, my extreme good looks. That's one thing. You understood that immediately, didn't you pick up on that? (Laughs). My amazing sense of humour. Number two. Again, you picked up on that, I know. (Laughs again) What makes me different? I'm just different because we're all different, you know, not anything special different. I'm just different. And, believe me, that's probably enough.

But, like most dealers, I'm just a dealer, so I fit into that block. And then everyone's slightly different, only in their own way.

Are you friends with other dealers, or are you always competitors?

We are always competitors, but friendly competitors. And that's the deal. That's what everybody understands. You know, we've all got our own businesses. Therefore, we all want to succeed. I'm not going to just hand over things because I'm a nice guy. I'm also not planning on being a nasty blow. I want to make money and do well. I think what I've learned in life is that you worry about yourself and don't worry about others.

I know some people actually don't live by that. A lot of people don't. But what I think I've learned in life is that there's enough aggravation in your own life that you don't want to worry about other people. And if someone's more successful than you, well, good luck to them. But as long as I'm successful, I don't care.

Do you have a book in your own library which you would never sell, or is there always a price for which you would let it go?

Always. Whatever you want, Una, it's available.

Bernard Shapero at 106 New Bond Street