The Keeper of the Things

An interview with American art collector Michael Lowe in Cincinnati

“Michael Lowe is The Dude,” a curator friend told me before I met the urbane collector of minimal and conceptual art, and he wasn’t wrong. Tall and handsome with a tousled mane of silvery hair, Lowe exudes an effortless cool. He is dressed in a charcoal grey turtleneck and distressed grey jeans when he greets me at the door of the Cincinnati townhouse he shares with his wife, Kim Klosterman. Nearly two decades ago, the couple enlisted the help of architect Eric Puryear to transform the nineteenth-century brick building into a modern, light-filled space with high ceilings and an abundance of white walls and built-in glass cabinets — all ideally designed to display their ever-expanding collections. (Also a collector, Klosterman focuses her interest on artist jewelry from the 1960s and 70s. An exhibition of 110 pieces from her collection will be on view in museums in Germany and Cincinnati in 2021; a companion book titled Simply Brilliant was published in February.)

Affable and laidback, Lowe is generous with his time and delightfully meandering with his responses, recounting one remarkable story after another, including many instances of meeting someone about one work of art only to encounter an even more noteworthy piece in the process. In much the same way, Lowe’s collection refuses to be confined to strict parameters, instead following the thread of his fascination, allowing one acquisition to inform the next. Artist books led to mail art led to Fluxus led to ephemera led to artist records — and on and on as Lowe’s insatiable curiosity continues to draw him through the vast and seemingly boundless terrain of conceptual art.

Over nearly two hours of conversation, Klosterman joins us from time to time and offers her own perspective on Lowe’s collecting philosophy and process. The admiration that the two share for each other’s collections is readily evident: each will share the other’s accomplishments and accolades when the other is too modest, and they often finish each other’s sentences, recalling names and dates that the other has forgotten. At one point in our discussion of the significance of collecting, Klosterman excitedly interjects with one particularly revealing anecdote: “I have to tell you,” she said. “I asked Michael what he was at one time. I said, ‘Michael, who are you? What is your purpose in life?’ And he said, ‘The Keeper of the Things.’ ”

While Lowe owns works by many of the major names in contemporary art — Marcel Duchamp, Josef Albers, Sol Lewitt, Daniel Buren, John McCracken, and Carl Andre among them — he is perhaps most passionate when he is talking about those whose work would have been forgotten — the ephemera of unheralded masters and overlooked genius — but for a collector’s commitment to safeguarding the objects and artifacts of our collective history. Lowe and others like him are indeed the keepers of the things that testify to our own messy, strange, wild and beautiful human existence.

You were interested in becoming an artist when you were in your early 20s. What attracted you to art? And what kind of artists interested you?

Lowe: As a kid, I was making collages primarily. There was something in me that made me want to make things. I loved writing and I loved making art. My mother was artsy, and we would buy used objects and repaint them. I just had a kind of strange interest in stuff: books, dictionaries, lots of images. I liked cutting them up and gluing them down. I still do that.

After I graduated high school, I was going to go to college but instead I got a job at Montgomery Ward, which is a department store — I don’t know if they’re even around anymore — and I was doing store displays. It was like art in a certain way: arranging objects and furniture and all that kind of crap. I did that for a few years.

Michael Lowe collection

Where did the impulse to collect begin for you?

Lowe: That was always there, too. When I was really little, I picked up crap and collected stuff, like objects in nature and comic books. And it was just there; I had no clue why. A lonely childhood, probably. [laughs] That’s what happens, I suppose. Being in Germany, [Lowe’s stepfather was posted there by the military] we would go on great field trips — boat stuff, Reineberg Castle — and see amazing early artifacts like paintings and armor. So objects always really interested me a lot.

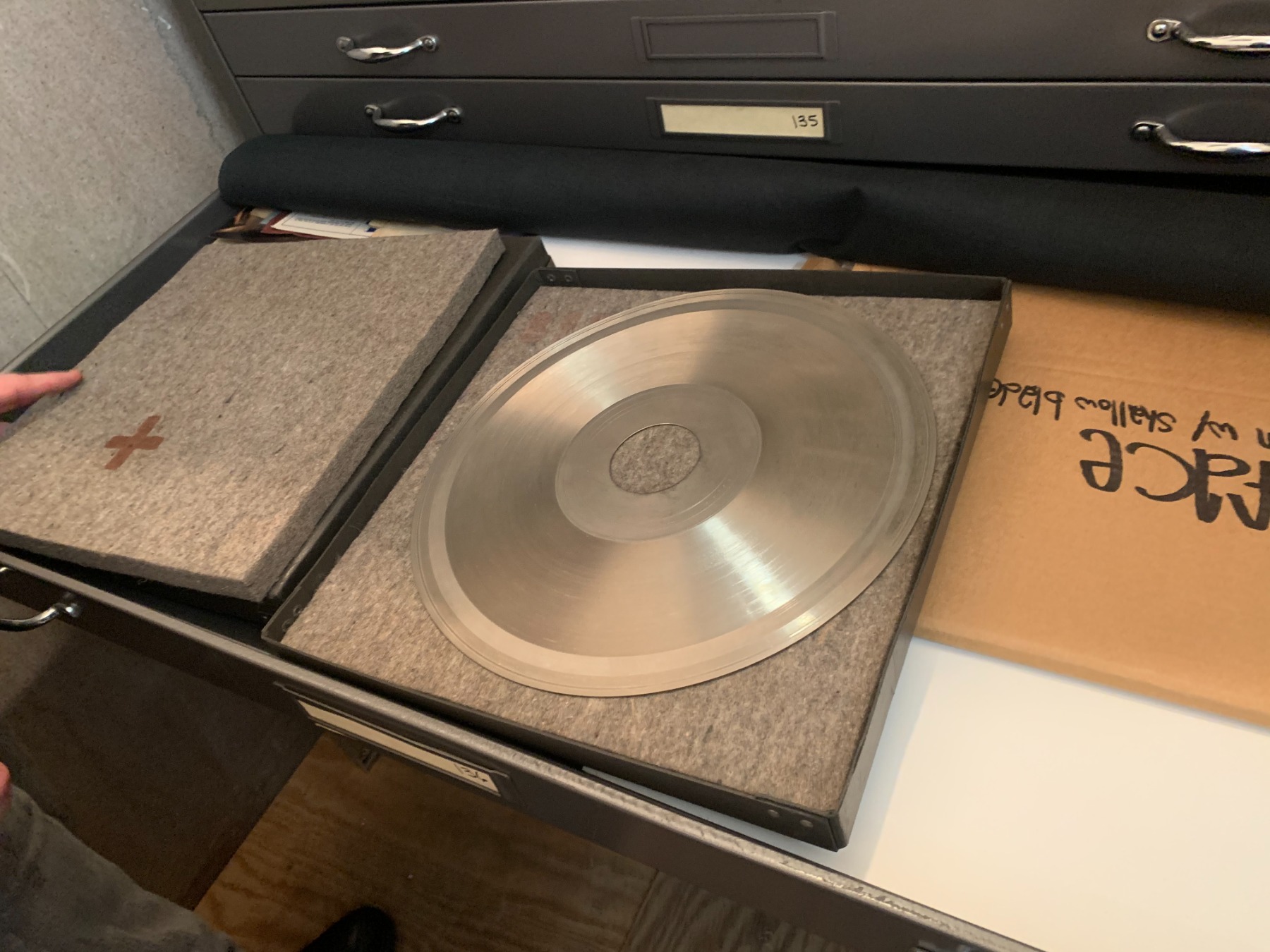

Joseph Beuys. Sonnenscheibe (Sun Disc). 1973

Where would you say your interest in contemporary art began?

Lowe: In high school! I started going to antique shops and becoming interested in older stuff. And when I started working, I bought little items: books and objects and prints. After a couple of years, that led me to quit my job because I thought, I’m earning nothing, really, and I could make this much and maybe more just buying and selling stuff. So I became an antique dealer.

I collected objects and loved books in particular, and found one publication called S.M.S., which was an editioned group of volumes by William Copley, who was an American who did amazing works and was an unbelievable collector. He commissioned all these artists to make prints, and then put them in volumes collectively called S.M.S., which stands for “Shit must stop.” I thought, “This is really cool.” I didn’t have that much interest in contemporary art at first — though I certainly knew about it — but I went to New York and met a woman who had the remaining part of the publication, and there I saw all of these artist books and multiples she had. That was the year — it was 1987 — I really started getting interested in art. I started buying more artist books and went to Europe with a list of people that dealt in that kind of art. I just loved discovering new artists and works.

I went to places in Amsterdam, London, and maybe Germany, and the most common thread in my approach was, “I don’t really know what I’m doing, but I’m looking for this sort of stuff, do you have things like it?” And they would say, “That stuff was purchased by Steven Leiber.” Everywhere I went it was, “No, Steven Leiber was just here.” Lieber was a San Francisco dealer in ephemera, artist books, artworks, all that kind of thing. He started as a photography dealer. So when I got back, home I contacted him and said, “Hey, I don’t really know what I’m doing, but I’m interested in this stuff, what do you have?” He faxed me a list and it just kind of went from there, with me figuring it out and doing research. I had a huge library and I would look people up and think, “That’s really interesting.” So my interest grew pretty quickly through artist books, primarily.

Michael Lowe collection

What was it that attracted you to artist books?

Lowe: What really interested me in artist books was perceptual, like, “There’s not much here,” and I was attracted to that. It was the opposite of what I had been doing at the time. My wife Kim and I were collecting and dealing in objects from antiquity to maybe the 1940s. We lived in a Victorian house we had renovated and it looked like a nineteenth-century collector’s place with Aesthetic Movement and Arts and Crafts objects. It was maximal, filled up with stuff.

Was there a moment when you really started to see yourself as a collector?

Lowe: I’ve always thought of myself as a collector. I truly always kept things. That was the point of doing what I did — I love keeping things. I know dealers who have collected and not kept anything. All of the money they make goes back into running a successful business. And I never had that idea. I thought, I’m going to buy works I really like, and buy enough of them, and to sell some, as long as I don’t go totally broke or insane. That was something I always wanted to do. I’ve never wanted to work for anyone else. I love what I do and it’s a learning experience every day.

Robert Gordon. “Untitled” ca.1969

Tell me how you decide what comes into your collection. Do you have specific pieces in mind or artists you're looking for?

Lowe: One thing that’s informed my interest is collecting primary documents — exhibition catalogs, ephemera, and that kind of thing from the ’60s and ’70s — and going through magazines and exhibition catalogs. I’ve focused on certain artists I thought really did amazing work, and there’s a mental wish list of, “Wow, it would be really cool to have something by this artist.”

Bill Bollinger was a really amazing artist, really well-known at the end of the 60s. He showed in Germany, and all over the States. And I always thought it would be fantastic to have a piece by somebody like Bill Bollinger. Nobody cared about him when I began collecting his work. There were works from that era in galleries and, probably now, they still have them in Germany. There were people who championed artists like this and probably people who were looking for these pieces.

Lawrence Weiner. “MOVED OUT OF FOCUS”. 1989. Christo, “Store Front Windows”. 1968

I had the chance to go to an auction by the Aldrich Museum, which was getting rid of its permanent collection. They had decided to focus on funding for temporary exhibitions and get rid of the stuff that they had from that era. I had all these documents, catalogs from their exhibitions, and realized, “Wow, they have all this amazing stuff.”And so, that was how I got my Bill Bollinger and my Gary Kuehn — the sculpture that you'll see out there in the hallway. To show you the general lack of interest, an issue of The Art Newspaper came out after the Aldrich sale, in which the writer referred to me, wrongly, as “a book dealer from Cleveland.” He didn't say I “had the nerve” to buy these works but was basically asking, “Why this guy?” in a way that suggested he was outraged that someone outside New York could get them. It confirmed that there was some interest — albeit no real interest — in these artists and for a writer, who knew something about this earlier sort of art, to get pissed off was kind of like a feather in my cap.

Robert Smithson. “Slate Grind”. 1973. John McCracken. “Plank”. 1979. Fred Sandback.

“Corner Piece”. 1972. Michel Parmentier. 1983

How has your collection evolved over the years?

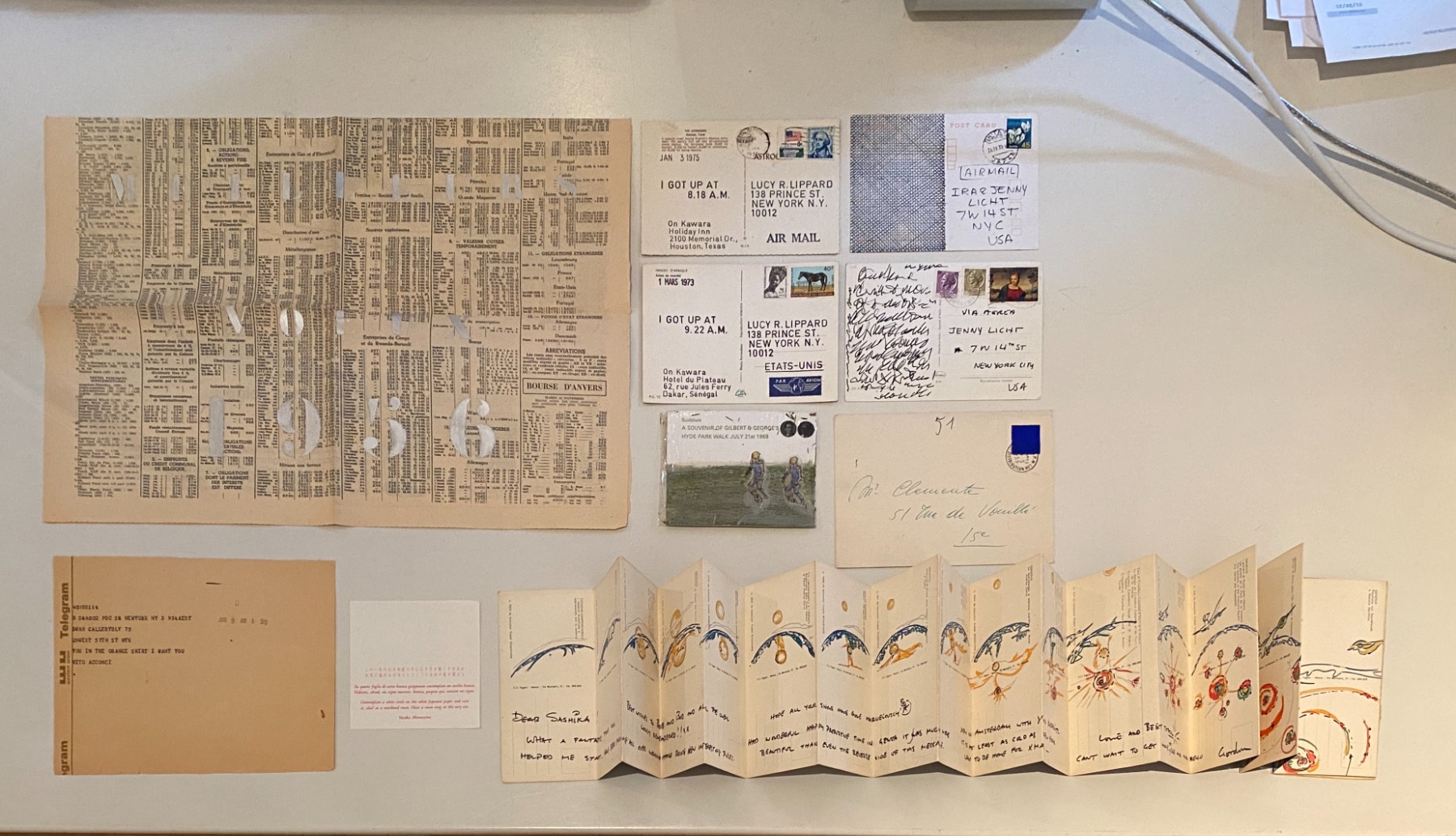

Lowe: I tend to revive certain interests. I go a little crazy trying to buy certain types of work. For instance, I collect mail art, art through the post. I had pieces I bought ages ago that were sitting around in boxes, and I got the idea to buy ones that were maybe not so obvious to me. I had pieces from Eastern Europe. I had bought collections of stuff. These things were laying dormant and I became more interested in them again. So I started searching for this kind of material; it’s not easy to find. I had to buy pieces from people who were involved in mail art activity during the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s. Some of these people have massive amounts of the stuff because they also collected it.I found a guy in Poland who was dealing in mail art, as well as Eastern European conceptual stuff that was, again, mailed through the post. I focus on particular areas of interest and accumulate that way.

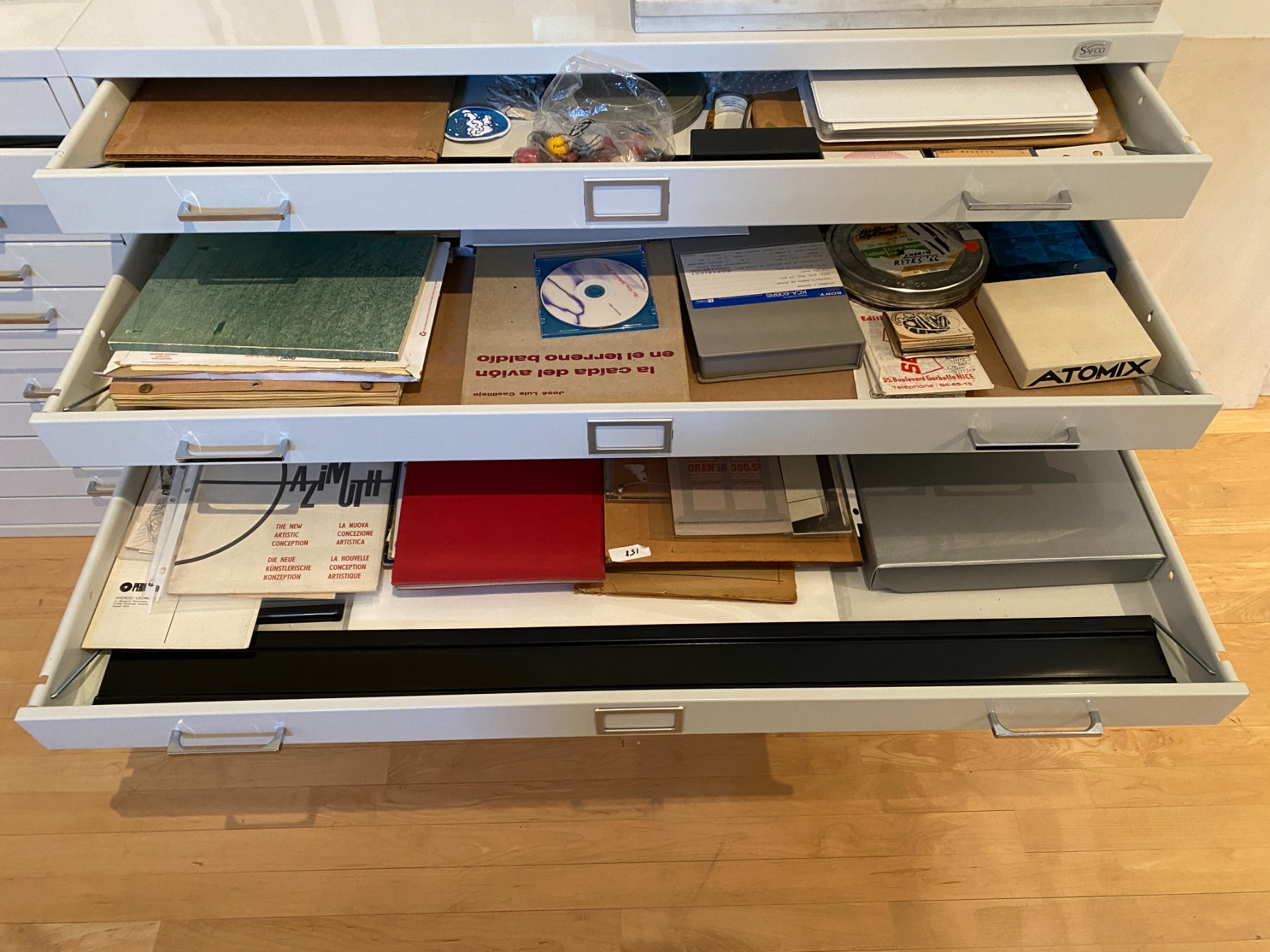

So what informs me a lot of times is an interest getting re-invigorated. For instance, I have a giant artist record collection. It’s like, I don’t know, 3,000 works, maybe. It’s something I have worked around and then gotten really crazy about again, with the thought that I should buy all this type of material and really make it the best collection ever.

With mail art, my idea for the collection was to buy works by major artists, more so than people who just kind of participated. There were majorly known artists who used the post as a medium: Sol LeWitt, Yves Klein, Ray Johnson — you name it. So I focused on trying to buy more of their works than the lesser known people. I also fixated on Japanese artists, on Japanese conceptual and mail art.

In researching this, one guy really popped out: Yutaka Matsuzawa, who’s kind of the founder of Japanese conceptualism. He came to the States in the late ’40s, early ’50s, and had this revelation that the art object should disappear. He was a poet as well. His works were kind of based on Buddhism and Zen. I thought, “Wow, the is my guy! I have to try and find this sort of thing.” So, again, I started locating people who might have pieces, all the mail art people. I have works of Matsuzawa in publications because he submitted works to publications that were artist-centric. That’s the only way these particular works exist. Thinking about Matsuzawa then led me to other people…. and the pile just gets higher and taller.

Michael Lowe collection

What’s the significance of collecting for you?

Lowe: It’s that rush that collectors get. You’re kind of a drug addict; you find something and then you acquire it, and then you’re just onto the next thing. It’s insanity. It truly is.

Are there purchases that have surprised you, works you found yourself buying based on a feeling or an impulse?

Lowe: I’ve often visited people to find one thing and had something else turn up. One guy I visited was a mail art participant, an artist himself, and lived in New York in a shotgun apartment he’d been in since the late ’50s, I think. He was a complete hoarder. There was half a stool for me to sit on in the kitchen area, which was piled with stacks of brown paper. As we talked, I was a little squeamish, squirming around, as I pulled papers out of the pile. I remember one was this amazing invitation from 1966 for a Robert Morris show or something. All of this stuff was cool, it was so interesting.

Just digging around in his place, I found fabulous pieces, from Fluxus people, pre-Fluxus, Yam Festival, Robert Watts — just amazing, amazing pieces. And then he mentioned that he had other works, stored at his sister's house in New York, that I might be interested in. He said, “I’ve got this Marcel Duchamp box [Boîte-en-valise], I have an Andy Warhol painting.” I replied, “Sure, that would be great if I only could afford it.”

The great story about the Duchamp box is that this guy had purchased it from an exhibition at a gallery in New York . He had gone there knowing all about Duchamp and said to the gallery owner, “Man, this is incredible but I can’t really afford it.” It was $150, and the owner said, “You really like this, you’re an artist, you understand about Marcel?” He replied, “Yes, of course, I do.” And the owner said, “Well, I’ll tell you what: you take this with you, sign this paper, and you make payments as you can.”

So, in response to my answer about affording it, this guy said he would also let me do just that. I made payments on this most amazing work of art that he couldn’t keep in his place anymore. He had sequestered it. It was a total shocker. It’s those kinds of visits that are just fantastic. I have a million stories.

The home of Michael Lowe and Kim Klosterman

And what about the people who visit you? How do you share your collection?

Lowe: I welcome anyone unless they seem like a serial killer. And so we’ve had whole groups of serial killers come here. [laughs] No, not really. But no, I’m very open. Museum groups primarily.

Others? I have had a couple of assistants — young artists, young poets in their late 20s and 30s — who have helped me catalogue my collection. They catalogue my mail art and Eastern European works and say, “Oh my God, this is so cool.” They develop a curiosity out of that and share it with other people. They’re learning about artists they would have never encountered otherwise because who gives a shit about a lot of this stuff? I would come home and they would ask, “Hey, did you know about this artist or that artist?” And I would point and say, “Yeah, there’s one right over there.” And they’re like, “Wow!” That to me is exciting, when people truly get something out of it. A lot of younger artists who really get it are appreciative. They say, “Wow, I have never seen one of these.” And I say, “Yeah, you probably won’t again.”

With museum groups, I explain my collection and try to enlighten them. My object isn’t to make people go out and do as I do. It’s more like saying, “Don’t discount the fact that this might look like crap to you; there’s something to it.” There was a museum group from Wyoming who were obviously interested in art, and maybe some of them collected a little bit. People were looking around the collection as I’m giving my spiel, and someone exclaimed “Oh my God, we’ve been to (this or that) museum and (this or that) collection, but no one’s ever explained it like this to us.” So it’s really good for people to hear an explanation. It’s not that I thought they would rush out and would become collectors, but it was satisfying for me to provide a little bit of information for people to begin to understand that there are different forms of art.

Like I said, I’m very open to anybody coming here and I’m happy to sit down with them. I enjoy it and I like talking to people, especially people who are curious. That’s the greatest thing to me. The only problem is that it is sort of hard, sometimes, to get my hands on something to show what I’m talking about. I’m not that organized. Because I have all of this stuff that’s small, like drawings and photographs that are in folders or boxes, it’s often a case of, “Where the hell is this thing that I want to show you?”

Mail Art by Marcel Broodthaers, On Kawara, Sol Lewitt, Gilbert and George, Yves Klein, Vito

Acconci, Yutaka Matsuzawa and Gordon Matta Clark

Your wife, Kim Klosterman, has joined us and she is a collector as well, with her own collection of artist jewelry from the 1960s and ’70s. Do you see any relation between your collections?

Klosterman: It’s funny, they do complement each other in the fact that they’re material from the 1960s and ’70s. And it’s unusual material from that time. But it’s highly unusual for us to go into a place where we can find jewelry and art of the same caliber together. But if we went to a show, for example, I’ve always said the two of us could go in opposite directions, and whether it’s an antique show, an art fair or a jewelry show, doesn't matter — we could go in opposite directions and then meet at the end of the show and each ask, “Did you see this, this, this and this?” And we would both have selected the same four things.

So I am a good scout for him when we’re not in lockdown. But I don’t have the knowledge that Michael has of his collection because it’s become so much his as I’ve veered off into my own world. It’s so vast now that it’s hard for me to keep up with him. But we do appreciate each other’s interests very much. It’s a nice dove-tailing, without anyone stepping on the other’s toes.

Lowe: Right. And the old collection we had, as far as the antique objects and stuff, we certainly collaborated on that, because the house is filled with that furniture and those objects. We both got it and liked it very much. So yes, we've been a good match.

Marcel Duchamp. “La Boîte-en-Valise (Series B)”. 1942-

Kim, you said you were a good scout. What would you say has been your best find for Michael’s collection?

Klosterman: Maybe early on, when I bought the Piss Christ photo. I think it was 1985.

It was an exhibition commemorating the 100th anniversary of photography. There were quite a few exhibitions in Washington, D.C. then. I went to them and I was just bowled over. At that time, photography was cheap. You could buy anything you wanted, you really could. You could buy the crème de la crème for $10,000 or under. $10,000 was huge. And at that time, people like John Coplans and Cindy Sherman and Andres Serrano were just starting to get their feet wet. They’d been making photographs, but it was a weird world because there was “the photography world” and then there was “the art world”, and the twain shall never meet. I think that was a real seminal point for these artists — who started using photography as their medium, — being recognized in the art world. I came back from those exhibitions and I said to Micheal, “We have to collect photography. It’s a no-brainer. It’s so great. We can buy anything.” So I started buying Cindy Sherman and—

Lowe: What was one of your first photographs? Serrano?

Klosterman: The very, very, first thing was Joel-Peter—

Lowe: Witkin. That’s right, yeah.

Klosterman: They were so creepy. It was the only one thing that stood out at the art fair for me. So that was the first photograph we bought. But the Serrano I bought early on, after it had made the cover of Time magazine. That’s when they tried to defund the National Endowment of the Arts. It was a really, really big deal. So I called Stux Gallery and said, “I want to buy something by Andreas Serrano, a photograph.” And they said, “Well, which one?” And I said, “I'm sure you don't have any Piss Christ available.” And they said, “No, we have the entire edition.” I wanted to buy one of the big ones and one of the small ones. But Michael was absolutely against it. He said, “It’s a stupid picture.”

Lowe: I said, “Ugh, don’t! Don’t buy that!”

The home of Michael Lowe and Kim Klosterman

Klosterman: So with my own money, I said, “I don’t care. At least I’m buying one.” And I bought one of the smaller versions for $1,200. But it was still big.

Lowe: The funny thing is, when we lived over there in the older part of the house, the whole place was filled with Victorian furniture and we kept the Serrano upstairs. And in that room, we had a red leather Art Deco chair and a yellow sofa. We would go up and Kim would do the spiel about the Piss Christ and people were just kinda like, “Oh God!” And I would say, “You know why you bought it, don’t you? Well, it goes well with the furniture.” [laughs] And people were just like, “Let’s get outta here.” Anyway, it was Kim’s idea to collect photography. Kim was much smarter.

Klosterman: My vision was much more mainstream. Thomas Struth would have been next. It was that kind of stuff. Michael’s version became performance photos and Vito Acconci. Edgier, more intense. And I really like those. I respect them and I think they’re totally cool. We sold all the other photography to help fund the building of our house here. I liked learning about photography, but I was never passionate about those images. For me, it was more of a savvy collection. I really am much more passionate about the images Michael has collected since then.

Michael Lowe collection

Have you seen collectors change demographically over the years? What about their motivations for collecting?

Lowe: Money is a huge factor. Art always had some residual value. But the money now is what you hear. You don’t hear, “Amazing painting sold.” You hear, “$52 million painting sold.” And that’s become the thing. There are a lot of collections that the collector will say, “Unlike anything else that you’ve seen.” And I think, “Really? But you collect only artists that everybody else has. What’s interesting about that?” I don’t begrudge anyone having super expensive art if they can afford it. If I had a ton of money, I’d buy works that I don’t have. It does seem to me though that many collectors are content to collect the same popular artists as their friends. Maybe in earlier days, if you had a Frank Stella, half your friends would say, “Who is that?” And the other half would say, “Frank Stella. Really?”

Michael Lowe collection

What do you see as the role of the collector within the art world, and within society?

Lowe: Something I have thought in this age of money is that collectors, especially really rich collectors, have the responsibility to buy very good things. I think you have to be careful because you’re leaving a legacy. I think if you have the money, you have the duty to buy good work — but I don’t even know what that is anymore. It’s a confusing time. It’s good and it’s confusing at the same time.

Takesada Matsutani. “Drop A“ 1970. Gary Kuehn. “Bolt Piece”. 1965. Robert Delford. Brown

wallpaper. 1960s

What would you say to a young person who hasn't considered collecting or maybe just thinks that it’s all out of their price range?

Lowe: Well, obviously, you can buy art cheaply. Although from what I know and do, I would add that I can buy something old that has a history. I hate to say invest in something. It scares me. What should I buy? I don’t even know why I do what I do and, I would add, I’ve gotten lucky monetarily, let’s just say, with certain works. It’s going to sound goofy, but the thing is, you just have to buy what you like.

Klosterman: I don’t know if the interest in collecting is waning because of lack of funds or just lack of knowledge. I think a lot of it has to do with starting in the schools. You don’t have art history programs like we used to. You don’t have the same level of connoisseurship because you can Google everything in one second. There is a big emphasis on experiencing over owning things. We don’t really have any young collectors around. I’m just taking a guess. I don’t know.

There does seem to be a market trend that encourages the experience versus owning an object. Why is it important to own objects and why is it important to have collectors?

Lowe: You’ll die if you don’t have things.

Nobuo Sekine. "Phase of Nothingness” No. 8. 1971

Title image: American art collector Michael Lowe and his wife Kim Klosterman