We should look for hope in art

An interview with Italian art collector Sveva D’Antonio

Naples-based Sveva D’Antonio and Francesco Taurisano are are among the most visible young art collectors in Europe. The pandemic has not stopped their activities; on the contrary, it has made Collezione Taurisano more visible as an institution interested not only in collecting and acquiring works of art but also in influencing the process, promoting conversation, and supporting young artists. In March 2020 Collezione Taurisano launched the live conversation cycle We Care on Instagram, which continued in various formats for most of the past year and can still be watched/ listened to on their IGTV channel. This not only made them very visible, but also became a site for artists, curators, museum directors and everyone else involved in the art process to talk and share their thoughts on how psychologically complex and challenging life had become in a world overtaken by a pandemic. Sveva D’Antonio is absolutely convinced of dialogue being a driving force, and also actively uses it as a collector. “My husband and I, we like to think that having a relationship with the artist, having the opportunity to speak about the work with its author, is really like an added value. You have the opportunity to get closer to a work of art and understand how its narrative interacts with the other works that you already have in the collection.” And conversation is precisely the thing that, in her opinion, can attract to art those who do not see it as their territory and to whom it is like a complex and incomprehensible riddle.

Continuing and developing the collection started by Paolo Taurisano in the 1970s, which focused on the most significant processes of the art scene at the time, Sveva D'Antonio and Francesco Taurisano focus on important developments and current events in today’s context so that they can “really understand how our society looked like at a certain time, what artists were doing, and what were our feelings towards the events that were happening all around us.” When asked if she believes in art’s ability to influence the global order of things and people’s actions, D’Antonio replies: “[…] you always think that just one person cannot make a revolution. But still, if each of us does something important every day, we can collectively influence change. […] With art, you can say a lot of things. If you stay inside of art you have the freedom that in a, let's say, ‘normal life’ you wouldn't have. Art can be a very democratic place to speak about things.”

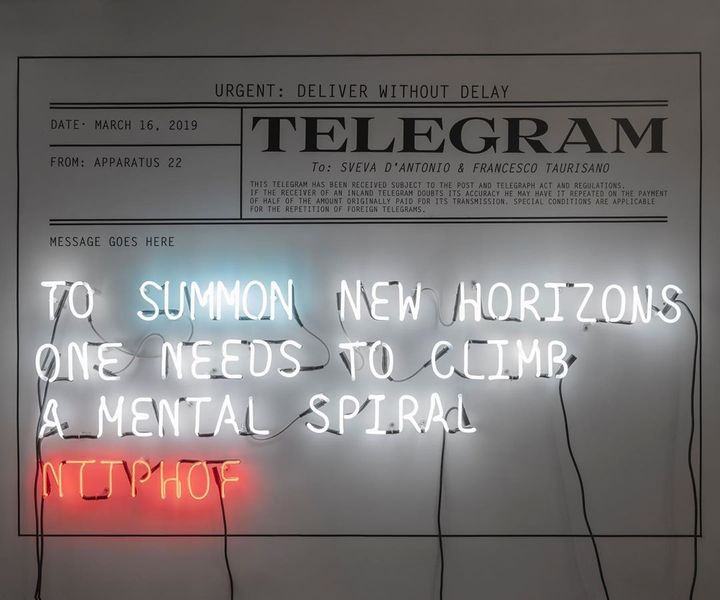

D’Antonio and I met via Zoom on an afternoon in early spring. She was at her home in Naples, which is also home to the Collezione Taurisano and is regularly opened to other collectors, curators and museum directors, and where artists are always welcome. One of these is the Romanian art collective Apparatus 22, the authors of the title Because of Many Suns for the Collezione Taurisano Acquisition Award given out at the Art-O-Rama art fair in Marseille – yet another testament to Sveva D'Antonio and Francesco Taurisano’s desire to be actively involved in the art process.

Apparatus 22 TO SUMMON NEW HORIZONS ... (to Sveva and Francesco) 2019,

white neon, red neon, black vinyl, telegram

From the outside, it looks like you have been very busy during the pandemic. You have conducted various live discussion series on Instagram, and there’s also the initiative Because Of Many Suns, the Collezione Taurisano Acquisition Award that supports emerging artistic practices and that is presented at the Art-O-Rama art fair in Marseille. Could you expand on these initiatives?

During the first lockdown in March 2020 we started a live series on Instagram (actually, live studio visits) with artist that we love. Some of them were already in our collection. We started this because it was kind of a necessity from our part, because when the pandemic exploded, my husband and I were in New York visiting residencies, artists, etc. But of course, on March 13 (a day I will never forget for the rest of my life) we were forced to go back to Italy because Trump was closing down the international air traffic. So, of course, we didn’t do enough studio visits while we were in New York. On the way back, we said to ourselves: we do not want to lose this opportunity; we want to do studio visits, so why don't we do it on Instagram? Then all the people who follow us, as well as the general public, can get to know these artists and participate somehow through interacting – despite the pandemic. Before we started, I spoke to artists and asked them if they thought it would be a good idea. And they answered – Yeah, yeah, yeah! This is super important for us. We want to speak with people and we want to show you what we’re producing, because we are producing a lot. So that’s how it all started.

Then we proceeded to do interviews with other people within the art system. When I was interviewing, our focus was – What are you doing right now to support artists? Because I think that even before the pandemic we were kind of losing the centrality of the artist; the artist had a very lateral part, a very lateral role, in the art system. And there was this invisible “god of the market” who controlled and directed us all. I think that during the pandemic, the artist has somehow revealed himself or herself again. And for us, there was this necessity to ask the people of the art system – What are you doing for them? Because they need your help. They need your support now more than ever. I think the response was quite positive.

Apparatus22, Perfomative Talk. 2019

Of course, there were museums that were doing more, and there were museums that were doing less. There were art fairs that were only shifting the physical fair onto a digital platform. I think that’s useless. But there were also art fairs, like Art-O-Rama in Marseille (it takes place every year on the last weekend of August), that were thinking – OK, now we have to do something digital. What are we going to do? So they conceived a platform in which the galleries that usually participated in the art fair could upload immaterial artworks – art that could be experienced through song, text or audio. And I think this was a very clever idea. In my opinion, it was the smartest way to translate art fairs into the digital world that I had seen that year. So we decided to give this award to them. The title of the award was given to us as a gift by the Romanian art collective Apparatus 22. We’ve had a very long relationship with them; they did a residency with us back in 2019. And we really appreciate the way that they are both artists and an art collective. They truly believe in the collective way of being an artist – proposing, conceiving and creating their work collectively. We approached them and said – Guys, we need a title for this award that focuses on supporting artists; we want to do something for the artists. They came up with a title that contains many meanings. A sun is a star that gives everyone light. And there’s also this concept of gathering people together (many suns), which is essential. Unfortunately, in this first year of the award it wasn’t possible for people to publicly gather, so we decided to do a series of videos in which the people involved in the fair talk about the moment in which they are living and how they are persisting through it. You can still see it on our IGTV. There’s also a contribution by the director of the art fair, Jérôme Pantalacci, as well as by its curator, Tiago de Abreu Pinto. They talk about what they are experiencing and how they see the future. (Even though this word has become so difficult because I always say that we cannot talk about the future. Look just to tomorrow, which is more feasible of achieving. The future has become a date that is too long and too far away from us. It’s very scary.)

Apparatus22, Perfomative Talk. 2019

The last thing we did on our Instagram TV was during the second wave of the pandemic. We asked a lot of artists to send us a two-minute video in which they describe the last work they’ve done. Not only on a material level but also the process that they went through while doing the work – influences or references, and all the activity encapsulated within the process of creation.

This one has been super interesting, and serious as well. The title for it was a quote by Jorge Luis Borges: What is going to happen is not the future, but what we are going to do. This concept was very present. It is also one of the way artists try to face the fear of presenting their work, which is a problem for some artists. Not all artists are good communicators; for some of them... their work speaks for them. They do not even have to have words. But still, I think it’s very important to be a good communicator as well.

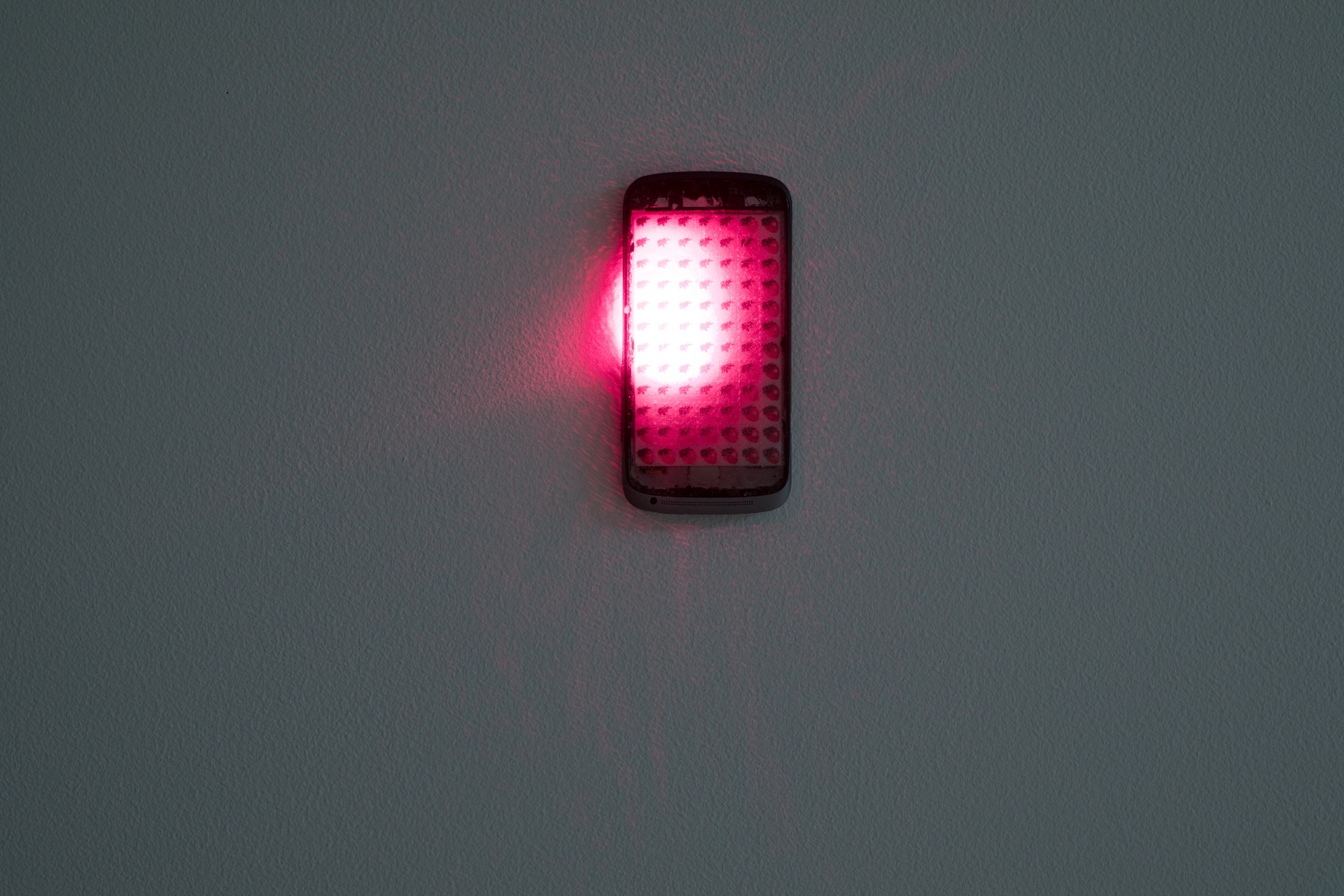

Michael E. Smith. Untitled. 2018. Cell phone, laser, LSD

The digital world is one of your communication tools. But what about art being on the net? Are you a supporter of digital auctions and viewing rooms within fairs? Do you buy art there?

No, never from the viewing rooms. But since the pandemic started, we have bought several works without first seeing them because we got them through galleries or through a direct relationship with the artist. But you know, I’m obsessed with dialogue; I love to speak. So before anything happens, I have to speak with you.

Of course, social media, like Instagram, is a super powerful instrument for discovering new artists. For example, yesterday I spoke with a very young Iranian artist. She fled from Iran five or six years ago to go to the United States and study art. She comes from a family of artists and now she’s doing her second year at Yale University in fine art. She’s a super interesting artist, and she’s doing very, very, very, very thoughtful work not only about the way she feels as a woman, but about the way her body is connected with objects and her surroundings. Being Iranian is really something. You are always inside a place that is closed, and therefore you develop very strong relationships with the objects that are around you. And what was interesting is that she called these objects “unwanted objects”. Because they are like an individual that you can relate to; it becomes the subject of the painting. I follow the Yale Alumni Instagram account (that is a very good school if you’re looking for new artists), and I noticed her. I contacted her and we Skyped yesterday. If it wasn’t for Instagram, how would I find out about her? If it was pre-pandemic times, I would fly to New York, but that’s not possible now. So I used the instruments that I have; and I hope, in a smart way.

Installation view. Collezione Taurisano's apartment. Photo: Maurizio Esposito

We are living in a turbulent and unpredictable time. How will this impact the future of the art world? Is it all bad, or maybe there is something good there?

If we’re talking about the art system in which we were living, I think it was going at too fast of a pace. It was impossible. It was too fast for the artists, it was too fast for the galleries. It was too fast for collectors as well. I think it was too much. The acceleration and pace were negatively affecting the quality of the work the artists were producing. So I think that this pandemic has taught us something.

It has given artists the opportunity to be in the studio by themselves, to think about their work and their practice as a whole, and to reflect on its development. Because I am an optimistic person, I want to see the positive side to this period that we’ve all been through. For example, I discovered a thousand new artists during this time, which is more than before. Of course, I saw a lot in the past, but now with everything virtual, I can meet an artist from New York at 6pm in the evening, then at 7pm another one from India, and then at 8pm another one from Los Angeles. All on the same day. I think this is really a precious thing that we have all experienced.

I don’t want to say that I was happy during this period because that would be crazy, of course. There were moments of depression for the majority of people here in Italy, where we’ve had many deaths and a lot of cases of people being very near to death. So I can’t be happy. But I think that art, and especially the dialogues that I had with artists, really helped me get through this period and to see how art can help society deal. The artist is really like a reflection of reality – they can give you a more in-depth perspective on what we are living through. We are used to using art as a therapy, and it really helped me, too. I am so thankful that I have the opportunity to collect art.

During the pandemic we’ve been saying that art can be a tool for healing – that it can help us live through difficulties. But how can one discover this power of art? How can we teach society to look at contemporary art and see its capacity for healing and helping? Otherwise it’s just words.

Yeah, that’s a very interesting question. You’re right, it’s not easy. Because first of all, contemporary art is not taught at school. So people do not have any theoretical knowledge about what contemporary art is. Most of the people I know, the ones who I hung out with, were somehow self-taught. Even for me, who has an academic background in art history and who studied in Italy and France, our “contemporary art” stops with the 16th, 17th centuries; it doesn’t even enter the 18th century. For us Italians, who are like a Renaissance people, this is the end. And so there is nothing left. Maybe we get one lesson about Picasso, but this is considered “pure avant-garde”, you know.

So most people don’t have the slightest idea what we, the people inside the contemporary art world, are even talking about.

Installation view. Collezione Taurisano's apartment. Photo: Maurizio Esposito

At the same time, with all of these social media that are very popular and very easy to use as an instrument to discover contemporary art, it still is very tricky. You can be very fascinated and intrigued by something that, in the end, turns out to be very superficial and purely commercial, without any content and without any important message to spread. So what I always try to give as advice is to trust people. I think that is essential in collecting contemporary art; even if you just want to get closer to contemporary art, you should start entering dialogues with people who are already “in” there. I’m talking about gallerists, other collectors, curators, art critics, people that somehow show a true passion for it – a passion that goes beyond the trends, beyond the pure aesthetic of the form of the artifact. People who have this sensibility towards contemporary art understand which people they should approach, because I also think that not all people have the insight to understand contemporary art. That’s because they’re going with what they were taught at school – the majority of people think that art is only created by classical artists like Leonardo da Vinci or in the Renaissance – a representation of reality that is very much in the past. I’ve always had the impression that people who haven’t studied contemporary art are just not into it. Art for them is something that does not to deal with the current times; it is something that has to hang on the wall at the museum. It will only tell you something about an event that has already happened; it is not something that is happening while we are alive. Whereas contemporary art is completely the opposite.

My personal experience was that contemporary art interested me. I think I just have this sensibility towards contemporary art. I began to go to galleries and ask people questions, I’d get to know them, I’d ask about their stories and the story behind the painting, the sculpture, or the installation, and I’d see if the works spoke to me. I think that’s how it started. It started with dialogue, with having a chat, with talking to another person. And that’s why we connected, and why we still connect so much with contemporary art.

Installation view. Collezione Taurisano's apartment. Photo: Maurizio Esposito

It could be that a dialogue didn’t establish because already well before Covid the art world had become decidedly arrogant and snobby. Is it possible that after all of this passes, the art world could become more personal, more locally orientated, more focused on the body of art and not on the status of its creator or its selling price?

I want to be honest with you. I don’t think it’s going to change. I don’t think it’s going to change because of a certain type of gallery that specifically focuses on blue-chip artists, these shining stars. Of course, a lot of people, and also new collectors, go to these galleries and are treated, sorry for the term, like shit, and but they keep going there and keep buying their works. There is a type of collector who wants to get frustrated for some reason – be on these super long waiting lists and do whatever it takes to get the blue-chip artists.

I do not support this system. I hate it when galleries act like this because I don’t think it’s good for the system. I’m not talking on a personal level here because I don’t care if you don’t want to sell me your artists. I mean, the ocean is full of fish. I’ll just buy other artists or, if I have the opportunity, I’ll buy them in a couple of years or whatever.

This fast pace before Covid was also a reflection of this attitude – of being arrogant, of being concentrated on the market, on proposing only blue-chip artists – and leaving the general public with the idea that this is contemporary art. But this is not true.

Of course, the market is a part of contemporary art system. We are talking about the business. You know, galleries are little companies. Their main purpose is to make a profit – that’s why they sell works. And we are buyers purchasing a luxury item. But at the same time, it’s not only a luxury item – you are also buying a dream. I’m always very romantic when I talk about art, but I want to do it that way and not any other way. Art, of course, has a value, but I have to have something more, you know, if I’m going to be crazy enough to have my collection. In less than ten years, I have collected more than 400 works. I have to be crazy. I have to find something more than just monetary value in a work.

Adelita Husni Bey. The reading / La Seduta, 2017. Single channel 4k

video installation, 7.1 Dolby surround, with silicone props, 15:33'' on loop

For us, it is like this trigger that challenges us to push the boundaries on what is collectible and what is not. For example, in the last couple of years we’ve bought a lot of, let’s say, “impossible work” works, like the work from the Italian pavilion – The Reading by Adelita Husni-Bey, which is a huge installation. Then we bought a purely audio installation by Lawrence Abu Hamdan, which is like an archive of audio recordings that he has collected over the years. We like to try, and even need, new ways of going further. We don’t want to stick to what is deemed traditional, or what is accepted by the majority of people. Which means not buying only blue-chip artists. I highly recommend that galleries should use different language. The problem that you mentioned does, of course, exist. They’re arrogant because they use a language, a form of communication, that is highly, highly segregated and that only people in this niche can understand – if you are not a part of this niche, you won’t understand a word.

I think another problem now is that beauty, aesthetic perfection, dominates over everything. That’s what they market. At the same time, they’re trying to create a commercial hipness around specific topics like gender or race. Topics that are super important and super sensitive. They understood that people had become fed up with nothing but an aesthetic form and that they wanted to see more in an artwork. People want to be committed; they want to be engaged in what they are buying. So the galleries decide – OK, now we’re representing a queer artist, or we’re doing a show with only women artists. But this is just another way to make these artists into blue-chip artists – something that can simply be marketed. Take the rise of black artists. They are everywhere, but at the same time, the interesting thing is that they are continuing to be segregated because now only Afro-American artists are taking part in some shows.

Opavivarà! Batuque na cozinha 2017. Aluminum bracket, rubber, wooden

spoons, aluminum kettles and pans

Do you believe that art has the capacity to change society, to make an impact on the way we think, how we act, and how we make decisions?

Yes. I actually believe in that. For example we have in our collection a painting by Zandile Tshabalala – she’s 22 years old and from Johannesburg, South Africa. There was an interview with her in a French newspaper yesterday, and they asked her the same question – Do you believe that your art can somehow change the world? And she said: Yes, of course. You know, I think that there is this necessity to have an impact on society. Because, of course, we all are living through a very tough period and we are all struggling in different ways. And by being an artist, you have the opportunity to say something important to our society and our community. You know, I think there is this need for being part of a collective. For example, Zandile Tshabalala says – I feel very supported by my galleries, by the environment that I’m living in, which is the art system. However, I’m usually the only woman in group exhibitions. And moreover, I’m the only black woman. So, of course I know I will not change the world, but I can still do something for my part. I can do something. And I think this is super important because you always think that just one person cannot make a revolution. But still, if each of us does something important every day, we can collectively influence change. I think this is the power of social engagement. Social engagement is not just a theoretical concept – it’s a practical act. An act that you have to do every day. And in the long run, you will definitely see change. But the problem is that the majority of people don’t do anything like this. They think – But if I’m the only person doing this, what will change? Nothing. Yet if every single one of us really does something important every day, we can, together, make change.

There are many works by women artists in your collection. What is the difference between art made by men and art made by women? Can you observe a more empathetic message in art created by women?

That’s a very tricky question, actually... Yes, we do have a lot of women artists in our collection and, of course, women can sometimes have a very intriguing perspective on a specific subject or specific topic. But then again, there is the value of the work that has nothing to do with gender, race, or nationality. The value is inside the work; it is in the way it relates and succeeds in spreading a message – in communicating the artist’s culture, sensibility, or struggles in a way that overcomes boundaries and overcomes labels. I think this is a very important message to pass on... Of course, we try to buy more art by women because we want to support them, and because I know very well that they are still not represented as much as men. Yet I do not want to produce the opposite result – that we have to buy their work only because they are women; I want to buy the works because they're valuable and because they’re good artists. They give me strength and power in the way they communicate through their work. And I think this is the most important factor.

What is it that makes art meaningful, in your opinion? What makes its value rise?

In parallel to being an art collector, I’m also an independent curator. I mean, I work in the art field as a professional. I’m creating a show in a gallery in Vienna (VIN VIN Gallery) in June with the title Collective Nostalgia. At first, I invited two artists. And then each of them invited another artist, because I wanted to create this process of inclusion that started from the artists themselves. One of the artists invited an artist from Pretoria, which is very peripheral place in South Africa. Her name is Cow Mash, and she’s such a character. She said that recently she was asking herself this question – Where do I look for hope? This had really obsessed her. We were talking about this during a session that I was doing for the artists, and at the end of the session, I repeated the question that she had asked at the beginning – Where do you look for hope? It was a very powerful question to be posed at the beginning, and we discussed it a lot. Another artist answered – I think in art; we should look for hope in art. For me, it was very positive to see that the answer was art.

With art, you can say a lot of things. If you stay inside of art you have the freedom that in a, let's say, “normal life” you wouldn't have. Art can be a very democratic place to speak about things. You can be hugely politically incorrect and not be censored or accused of anything because you have this freedom. I think we have to keep this in mind, because it's very important and we have the right to do it.

Installation view. Collezione Taurisano's apartment. Photo: Maurizio Esposito

It appears that a characteristic of today’s art world is to overdo it with the political correctness, even to the point of misconstruing things. Over the last year, several museum directors and curators have lost their jobs in the name of political correctness.

I don’t think that’s the right way to go. Look at the Philip Guston show that was canceled. I don’t see the point. I mean, now more than ever, you have to show Philip Guston. When are they going to show it? When we’re dead? Will this be the right time? This is the right time for art critics to raise their voice and say – We are annoyed. We are fed up with political correctness; we are fed up with the correctness of the boards of important museums all over the world; we are fed up with that. I think art critics see this and other huge issues, but they do nothing. It would be interesting to find out what they really think, without any filter. Jerry Saltz, for example, is very criticised, and I can understand why, but he tries to be honest with himself, at least. The only focus that the majority of art critics have is to please museum directors or to please whomever they have to, instead of being somehow pure and honest to the art they are talking about. You have to protest, and you have to raise your voice, and you have to go out in the streets.

I really think that art should give you a reason to go out into the streets and protest, to fight for your rights somehow. To fight for the women who are not represented, to fight for all the minorities who are not afforded civil rights in a lot of places in the world. To fight for countries where there is no democracy. Art can plant this seed in your brain and in your life – that a territory for art exists in the world. If we only believe that it can exist, it will become real. I truly believe in what a lot of philosophers call utopian realism. If you have a certain vision of art, you arrive at this concept of utopian realism, which is, of course, romantic. But keep in mind that the word "realism" must go along with “utopian” in this case. It brings us back down to earth and reminds us that we have to deal with reality, we have to deal with everyday life.