Let’s make future art history

An interview with artist, curator and collector Shiva Lynn Burgos

Iveta Gabaliņa

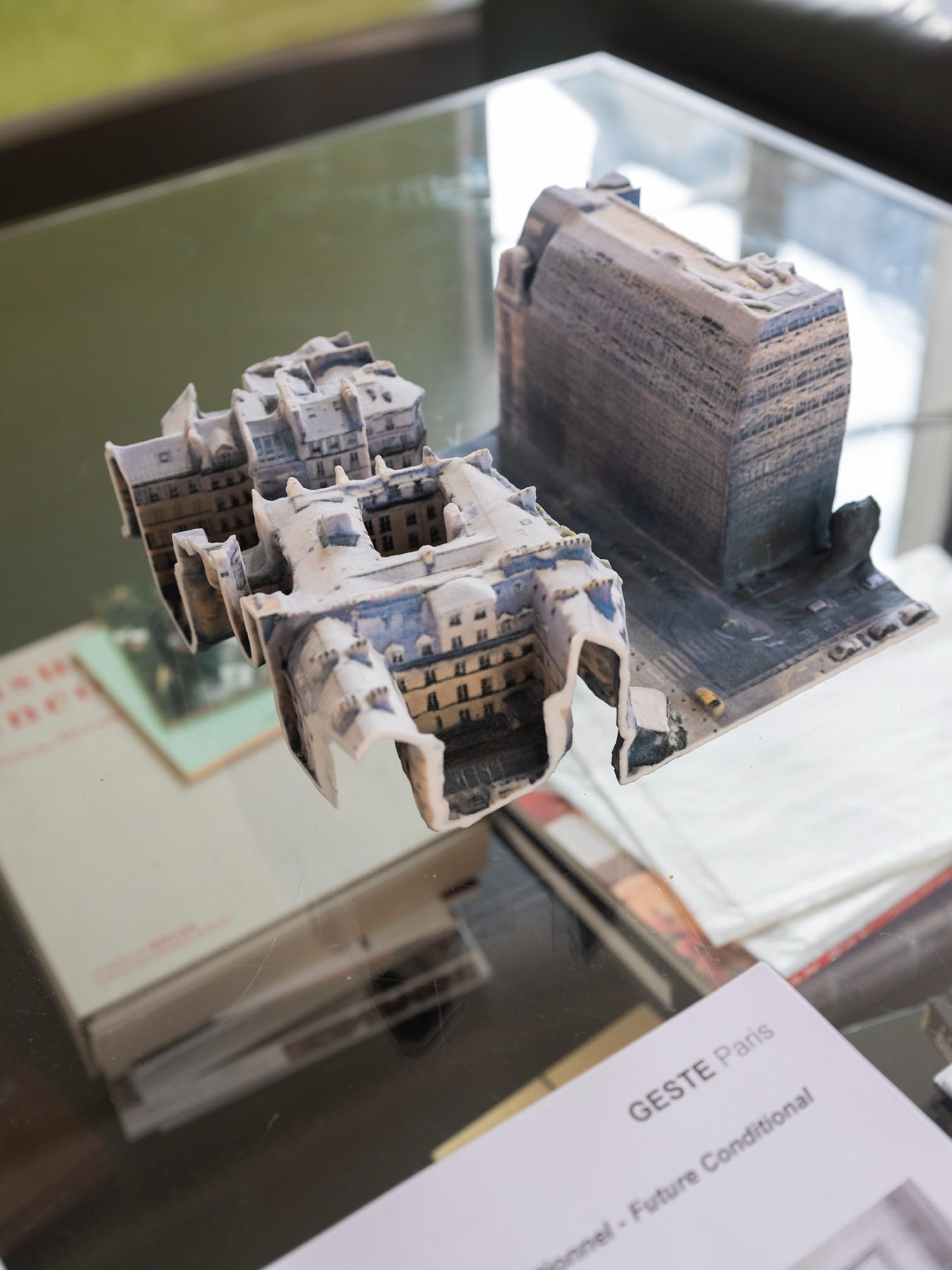

Every year during the first weeks of November, Paris becomes the spotlight of the photography industry. The epicentre no doubt is Paris Photo, but the city can offer so much more. Numerous exhibitions, artist talks, and book fairs are also part of the “Photo Days” network, in which the whole month is dedicated to the medium of photography. One could easily get confused by the variety of photographic experiences on offer, but if I were asked to suggest a special one, I would choose GESTE Paris. Located in a private Parisian apartment right near the Louvre, GESTE Paris offers an intimate exhibition experience with a carefully curated selection of art.

“GESTE Paris annually brings together vintage and contemporary works by both established and emerging artists. It is committed to experimental processes and invites photo-based artworks from outside the normal bounds of photography.”[1] Alongside well-known works by artists such as Hiroshi Sugimoto, Man Ray or Wolfgang Tillmans, there is always someone new to discover, either in the comfortable kitchen or the timid space of a “powder room”. The idea of opening this private apartment to the public in the form of an exhibition – and more importantly, as a space for social gathering – belongs to Shiva Lynn Burgos, an artist, curator and, together with her partner Dominic Palfreyman, also a passionate collector.

Photos: Iveta Gabaliņa

“Future Conditional”, the title of this year’s edition, questions the notion of the future in relation to art, language and philosophy. As stated in the press release: “Creative practices of future-conditional knowledge-making unavoidably draw on dominant imaginaries of socio-technical and environmental futures, hypotheticals. Questions of uncertainty, invisibility and post-photographic prototyping arise”. On a bright sunny afternoon we discuss the future of art, photography and NFTs, and how the idea of GESTE Paris came to light – all while surrounded by works created by Michael Wesely, Joseph Kosuth, darktaxa-project and many others, screaming in silence about the future we are forming right now, at this and every moment of our lives.

Although “Future Conditional” is part of Photo Days and is rooted within the medium of photography, most of it is of an experimental nature. Would you say that this is what is at the core of the GESTE Paris concept? And does this also apply to your art collection?

The collection started way before GESTE, which is in its fifth year now. I started collecting in my early twenties. My husband Dominic has been collecting art since the 1980s – he started with a lot of experimental video and photography even before photography was thought of as an art form to be collected. And the line where we agree and what we love is often the one where we have built this collection from. These can be vintage works, like Man Ray, August Sander and Hiroshi Sugimoto, but just as well it can go more contemporary, like Wolfgang Tillmans or David Jang. The line my husband and I both love is where photographic materiality and experimentation are part of the process, and GESTE Paris is derived from this. The name “GESTE” comes from “gesture”, and it is related to the philosopher Vilém Flusser, who had a way of describing how the gestural aspect of photographing is somehow enslaved by the machine. When you can work beyond the machine – or without it, or playing against the machine – then the gesture of the photographer can be more visualized. So that’s part of the game. The first show we did was called GESTE – it was basically just objects from our collection and it took place during Paris Photo Days. We thought we would have cocktails, invite people. Other friends brought some of their works that they wanted to show or offer for sale. The second year, we decided to do an exhibition. That’s when I met Mark Lenot. He wrote the book “Jouer contre les appareils”, which basically means playing against the camera. We curated the show together and I also invited Georg Bak, who works with generative art a lot. The next show was called “Binary / Non-Binary” – an interesting question about yes/no, black/white, and opposites; we started with some historic works from the first computer-derived art. We had the first blockchain artists, such as John Watkinson from CryptoPunks and Rob Myers, and then we got into artificial intelligence – all of which was very much digital. The “binary” and “non-binary” entered into ideas of gender – we featured young people who either define themselves as non-binary or choose to not define themselves in a binary sense, photographing their own communities. That was a great juxtaposition and somehow everyone could resolve these issues – and that’s the idea. As an artist inviting other artists either through an open call or the curating process, I want to pose a question or open an issue that facilitates entering the conversation.

This was also one of the questions I had in mind when thinking about your role as an artist. How does your personal creative practice influence your collection as well as the shows you curate for GESTE Paris?

I have experimented a lot with digital art, artificial intelligence and virtual reality. I made my first film in 2016. I do enjoy the questions surrounding photography. Is photography dead? It’s just like the question: Is painting dead? But I also always revert back to the roots, the origins of image making, as well. For example, here I have been experimenting with cyanotypes. They ground me in the process itself. When we can see the basics, it gives us a foundation for greater exploration of quantum image making or futuristic concepts of how we think technology will affect how we see things – much like how the cyanotype was a huge technology in the late 1800s. It’s more about society adapting to technology.

This definitely relates to the current show called “Future Conditional”, which deals with questions such as how our current actions are already influencing the future.

In this exhibition we wanted take you on a journey where you can confront your own present and future possibilities – hypotheticals: “we can”, “what if”, “because of”. It is also attached to language. One of the pieces we have is by Joseph Kosuth, who uses found images and a lot of text. We also have a work by Anthony Haden-Guest, who calls himself a cartoonist – there is a sense of humour in what he does, and he doesn’t even consider it art.

Turning back to photography, how do you see its place in the art of the present day and the future?

“Future Conditional” relates to art in the way that it is dependent on the conditions of making a work of art. First of all, we need to have the freedom to make a work. If we were in a state of war, no one would be taking pictures with their cell phones. Everybody is a photographer in some sense. There is a democracy about taking a photograph. Today, a small child can take photographs from the time they are three years old. Does that make them an artist? It’s also how the image makers define themselves and the tools that they choose to use. We have the new media, but then there is always the counterbalance of going back to the old materials such as using real film. I think because there are so many images out there, finding something that’s outstanding is more difficult now – because of the sheer volume and our shorter attention spans for looking at images. The decisive moment still exists, but there are very few people in society who can appreciate it.

For some time photography was related to the concept of death. It was something that had happened in the past. With the new media, and particularly with social media, this Sontagian and Barthian notion of death has transformed photography into a communication tool. It’s not so much about the past anymore but more about the present. And the way we consume images nowadays makes it even more problematic for photography to find its place as an artistic form of expression.

I think the photo world will remain in a bubble that is separate from the contemporary art world. There are certain artists who cross over. It is a question about identity. People define themselves as either photographers or artists. For example, Andres Serrano. He considers himself an artist, but he uses a camera because he wasn’t good enough at painting. His choices are also informed by his education in art history. A lot of photographers enter their field by studying the history of photography. They can be photojournalists, so for them, there is a whole other world based around publishing, creating books, perhaps doing some exhibitions, but they are not winning prizes – which is very different from the art world, where a photo can becomes an object with great value. It’s where you position yourself within that world that allows you to cross over into the contemporary art world.

I also want to mention that part of the curation process is to invite young artists for whom this might be their first show. The thrill of that is to allow them to be in dialogue with great works that might have inspired them. And it’s very democratic – there is no hierarchy. We have this small powder room where some of the best artworks go – Sugimoto, for example. These could be called “more challenging” or “naughty” works. For instance, we had a whole installation of Laia Abril’s works that were based on a serial killer – it featured a red light and you needed to experience it with a torch. The way we use this home to create a journey with the works is essential.

Regarding the place itself, you also have a beautiful home in London. What was the main reason for opening up your Paris home to the public?

I’m an American from Brooklyn, NY. There is this romantic ideal of Paris and its salons – Gertrude Stein, the interesting thinkers that would get together... I didn’t see that here, living in Paris. So we created our own version of that. And the French people who come here says it doesn’t exist. People don’t open their homes to strangers. It’s very rare. What they like is that this home environment allows people to relax. It’s not the white cube where you don’t even have a seat; you have a comfortable chair with a coffee or a glass of wine, and the opportunity to sit, look at the books, have time with the work… and often some brilliant conversations have sparked amongst the guests. It is a bit of a salon atmosphere.

“Future Conditional” takes place during Paris Photo week, however, the experience one has at your show is completely different – as well as in terms of buying works, because the potential buyer gets to experience the work within a home environment.

At GESTE Paris not everything is for sale, but we don’t deny the opportunity to sell works. We try to invite collectors, journalists, and people in the industry as well as the general public. The fairs themselves, if you go on Tuesday night to Paris Photo, it is not crowded and you can have an almost museum-like experience and really spend time with different works. On the public days it is almost a social gathering. It’s a cultural experience, and beyond that there are books being sold. It’s a trade fair; they could be selling electronic ovens or cars. It’s an atmosphere of a trade fair. I’m not sure if the fairs are dying – it was so busy and full of energy, and I think there were a lot of sales for some galleries. People like to buy things that they can see and touch rather than through the internet. They want to see the gallerist, they want to know the gallerist, maybe meet the artist or maybe not. And a lot of the photographers are present, so you have the opportunity to meet them. There is a whole culture around it which I don’t think is going to go away because it’s also a community where people want to be around each other. The commercial aspect of the fair depends on the curation of the fair, and Paris Photo, in that sense, is probably the best in the world. There is always something that you see that you haven’t seen before. It catches our curiosity in a way. But there is also a VIP experience held at the fair on Sunday afternoon, and how much you are involved in the industry is what shapes your experience there.

Continuing with the commercial side of art, we cannot skip over the NFT phenomenon.

It’s become trendy because money got attached to that. People selling for 60 million suddenly set this precedent where everybody wants to be involved somehow. Or it’s the opposite – they don’t understand it, they think it’s the end of the world. When we did our show “Binary / Non-Binary” in 2018, where we had original CryptoPunks and works by Rob Myers, we were able to explore what that meant. Objects that only exists on the internet. It was called blockchain art; NFT is just the non-fungible token, it’s not the artwork itself. It’s just a way to give provenance and trade; it’s like a collectible. I think the earlier digital artworks were less involved in their artistic merit and not in a style that we were used to collecting, i.e. coming from a more informed context. I see the whole space as another medium and the more I’m involved with it, the more I do see a future for it – at least in the short term. There are wonderful works that are experimenting within the digital space, and there will be things like, for instance, a picture of my cat that I turned into an NFT. Where the future of this is headed is one of the topics we have in our talks programme, “Quantum image making, post photographic prototyping, and the future of NFTs” – covering ideas like, for example, that quantum computing has the potential to mine bitcoin in fractions of a second and decrypt what’s encrypted. Will this idea of blockchain permanence still exist in five years, or will have artificial intelligence and quantum computing become more clever than this platform? I don’t think it’s permanent...well, nothing is permanent. I see it more like a medium.

I also do see a future in NFT but in a slightly different context. I see it as social media for art. A very important component of NFT is the community itself that forms around that phenomenon. By possessing a collection of NFTs, you also build your own identity as a collector which you can share among the like-minded. It’s a new way of communication, like an “Instagram” for a specific type of collector. Like you said, it’s a medium.

The idea of provenance and a digital ledger is where the value is in the whole system, but it’s very closely attached to cryptocurrency, and that’s where its fragility lies. And it’s also based on all these computers being able to run, which is also not very ecological. And then think about all the bitcoin miners who have lost their password code – how can the security of all this be ensured? I think everything that can be hacked will be hacked, and that’s part of the beauty of it. Imagine a self-hacking NFT that disappears – that’s the future. There should be some humour in it as well, but just turning something into a successful NFT requires a community behind it that sees it as valuable. It requires, in my opinion, an outlook along the lines of – let’s make future art history and not just things.

Shiva Lynn Burgos. Photo: Iveta Gabaliņa