A collection in the middle of now/here

An interview with French art collector Renato Casciani

Renato and Catherine Casciani’s art collection dates back to 1997, but their passion for art goes back much further – Renato Casciani can trace his love of art back to his childhood, and today, together with his wife Catherine, is actively involved in the regional cultural life of Upper France as patrons of various art institutions such as the LaM of Tourcoing (Lille Métropole Museum of Modern, Contemporary and Outsider Art), the Villa Cavrois, and Le Fresnoy (a postgraduate art and audio-visual school). As most notable art collectors in France, they are members of The Association for the International Diffusion of French Art (ADIAF) – a French association of over 400 contemporary art collectors committed to supporting artistic creation. Renato Casciani is also the chairman of the association “Friends of FRAC Nord-Pas de Calais” (a public regional collection of contemporary art). In addition to all of that, Renato has also curated about 20 art exhibitions, mainly in Lille and the surrounding area.

My conversation with Renato Casciani took place in October 2022 at the Moxy Lille City Hotel in Lille, France, where the Around Video Art Fair – founded and organised by the Cascianis – has just finished. This was the second edition of the fair, the latest challenge for the collector pair who see it as a meeting point for video art lovers and new enthusiasts alike.

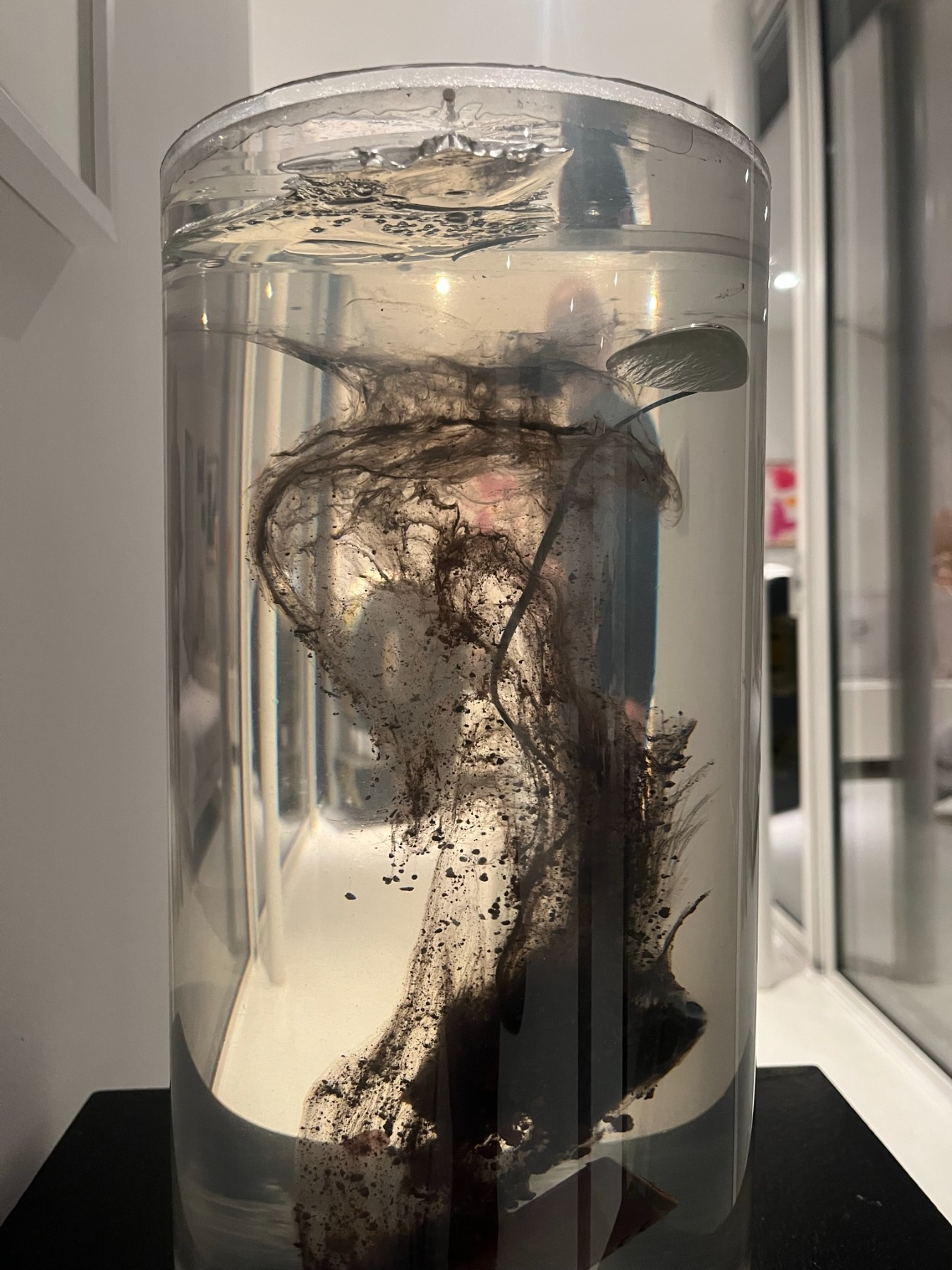

Haily Grenet, director of the Around Video Art Fair, also sat in on our conversation, helping with translating from French and occasionally contributing to the conversation with a comment describing Renato Casciani’s personality. The collector is generous with metaphors and also loves to get his point across with puns. Wordplay inevitably appears in Renato Casciani’s art projects – for example, in the title of the Around Video Art Fair’s prize, Now/Here, as well in the exhibitions that he has curated, for example, De l’Autopsie à l’Utopie (From Autopsy to Utopia) in Lille (2022) and Pourquoi faire; Pour quoi faire (Why to Do; For What to Do) in Ixelles, Belgium (2022).

Our meeting is not long because both Casciani and Grenet have to take down the Around Video exhibition, and Renato makes it a point to always be present for this task – another indication of the collector’s character, much like the portrait of themselves that the Cascianis sent to accompany the interview: a digital-era reference to the Arnolfini Portrait by Jan van Eyck. It is their official portrait as collectors. As Grenet comments: they wanted “to erase” themselves, not be on the stage, not be too frontal.

How did you get involved in art collecting? When did you start?

I always loved art. As a child I painted and drew a lot, and I have always been interested in exhibitions. However, I have a medical education and I work as a general practitioner in a town near Lille. My family were immigrants from Italy; living here in the North of France, they worked in mining.

When our children grew up, we had more money for ourselves, so we started to increasingly acquire artworks. It’s been 25 years since we started to collect art.

You said you made paintings and drawings in childhood. Have you ever studied art?

No, I do not have an art background. However, I have done about 20 exhibitions as their curator – mainly in Lille and the surrounding area, as well as in Bordeaux, Paris, and Brussels. The Around Video Art Fair was made on the basis of an already existing structure – the association called Now/Here.

I’ve had a neon sign made that says Now/Here, referring to that. I have it at my home, and when somebody arrives, the sign lights up – as my house is located “in the middle of nowhere”, I use a play on words between “now” and “here”.

And in my office, I have a “self-portrait” – 300 Polaroids of my patients. Without them, I wouldn’t be a doctor. Without the other person, we are nothing. That basically sums up what I do and what I want to say.

Photos: Haily Grenet

How many artworks are in your collection?

150; about 30 of them are videos. And we also have a collective collection with 16 other couples – the whole group together is called Cadre blanc. Each of us invests 150 euros per month, and then at one point there’s enough that we can by an artwork with the collected sum of money. The acquired work then travels across 16 houses, staying in each place for one year. It is the same philosophy of sharing as for the Around Video Art Fair.

We’ve been collecting in that manner for seven years. If we collect 20K euros per year, we manage to buy quite big names and large-scale artworks. For instance, we have works by Bruce Nauman, Davide Balula, Edith Dekyndt, Erwin Wurm, and Daiga Grantiņa. But we’ve acquired quite a few works from young artists as well.

How do you see the future of this collection?

In three years, our contract within Cadre blanc will be finished, since the original contract was only for ten years. We haven’t decided yet what we will do after that – either we will renew the contract, or we will sell some pieces, or maybe we’ll donate the artworks to museums.

Have you thought about founding a museum in which to house the collection?

Perhaps. [Smiles.]

How do you choose which artworks to acquire? Are the decisions spontaneous?

It depends. Sometimes it is spontaneous, but usually I need some time to think and to reflect.

Haily Grenet: This is my perspective of how Renato collects – he reads a lot, he is self-taught, and he goes to a lot of exhibitions and galleries; he speaks with artists and gallerists. It grows in his mind. Since he collects together with his wife, they have to choose together.

Is it difficult to create a collection together?

Sometimes.

Looking at works from your collection at the exhibition From Autopsy to Utopia, I get the impression that the topic of “the ego” is very present in your collection.

It is not necessarily about the ego – it is more along the lines of being anti-narcissistic and against the ego. I believe that today’s hyper-narcissism is the cause that has led to climate change and many other problems in the world. Because of that, we can no longer be in communication with others, with nature, with the world.

We have many self-portraits of artists in the collection – all of them are making fun of themselves. There is a self-portrait of Erwin Wurm with a plate of spaghetti on his head; a portrait of Tony Oursler – a drawing in which he is shooting himself with a gun but the “blood” on the paper is made of glitter. It is like la petite mort (a little death) – this is how we call sexual ecstasy, an orgasm, in French. You have to lose a little bit of yourself to get to the ecstasy. It’s beautiful, I think. And there’s a little play on words, too. The same idea, in a way, runs throughout the collection.

I like what Deleuze said regarding humanity becoming a woman. It means you have to stop having power in order to have power. Being less powerful brings actual possibility to experimenting and being more powerful. This is also about the play on words between impuissant (powerless) and un puissant (one in power), which sound the same in French.

Although I am not religious, I’ll give you an example from the Bible. I find it very beautiful. Sometimes a brutal person might be extremely touched by the fragility of a baby. This fragility is a bit like the story of Jesus. He is a little baby who becomes God because he is so fragile. In front of the powerlessness of a baby who is completely dependent on others, the [brutal] power might stop. Fragility can be an enormous force.

You seem to play with words and phrases a lot. Are you interested in language and linguistics as well?

That’s what French is for. A language that is made for wordplay and double meanings.

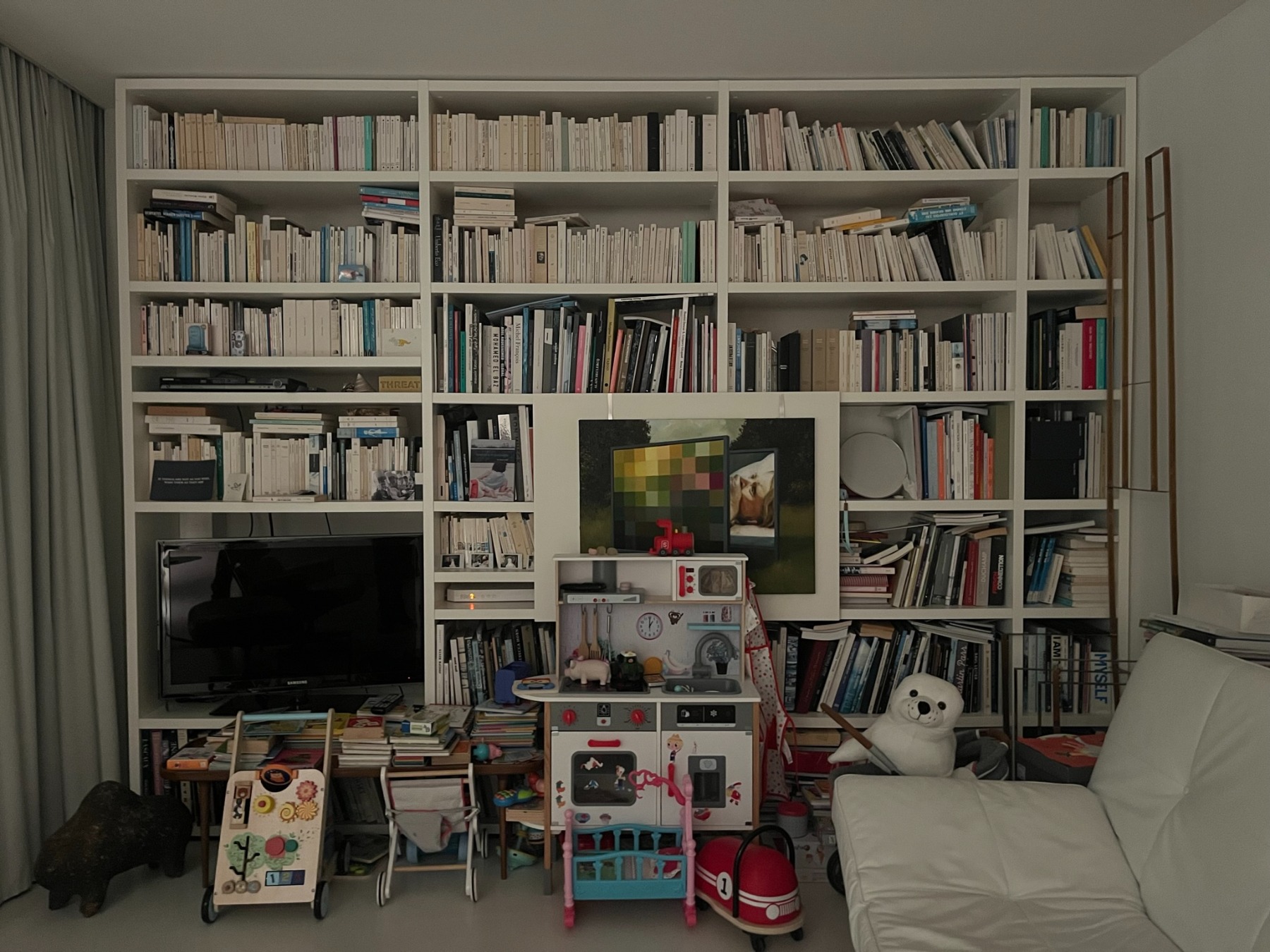

Haily Grenet: He has a huge library with a lot of reference material on art history, of course, but also on philosophy, literature and poetry.

Which artworks do you live with on a daily basis?

Smile Without a Cat (Celebration of Annlee’s Vanishing) – from Pierre Huyghe and Philippe Parreno’s project No Ghost Just a Shell. The project takes the title from the Japanese cyberpunk manga Ghost in the Shell. Huyghe and Parreno purchased the copyright from a design agency (that produces and sells computer files for cartoon characters) for the unpublished background character Annlee. They invited thirteen artists over a three-year period [1999–2002] to create stories and scenarios with the aim of further multiplying the range and reach of Annlee. Each artist’s project is a “chapter” in the evolving story of how the character fills its empty “shell.”

Smile Without a Cat by Pierre Huyghe and Philippe Parreno is the last artwork with Annlee – she manifests as her silhouette in a series of fireworks and finally disappears in the sky. I have four photos of Annlee from it.

At the end of the day, she is not dead because there are still works by other artists. There is a new life with each artist. As to the title, it is a link to Alice in Wonderland – where the cat disappears and leaves only one last visible trace: its iconic smile, to make us smile again.

To share with others – that is the main idea of the Around Video Art Fair. It seems you really do like to share art with others. Are there any works that you want to keep exclusively for yourself?

I don’t know, perhaps Davide Balula’s piece.

You said you have about 30 video works in your collection. What is it that roused your interest in video art?

It came naturally; day by day we started to get more and more into it. Besides, I found it very much in line with the current times. And there are no storage problems. (That’s a joke.)

What was the first video you obtained? Do you still own it?

A video by Edith Dekyndt. There is a white flag floating on a white cloudy sky – it seems to be disappearing and “becoming sky”. And in the same way, it “becomes” a philosophical concept of Gilles Deleuze.

What is your feeling about the video art scene and market in France – and in the world – right now?

The market is quite low, and private collectors are not very keen on buying video art; however, there are institutions that are acquiring a lot of video artworks now. What will stay and remain a part of art history is that which will have been held by the institutions. Everyone has a smart phone now, so it is possible to both access and make videos, animations and moving images quite easily. The new generation will be doing this more and more – that is where and how video art will grow.