The Barstad Collection

A conversation with Next Gen Norwegian art collector Henrik Barstad

While Next Gen collectors enter the art world for various reasons, Henrik Barstad stands out as an exemplary collector who started collecting art at a remarkably young age, even before he could obtain a driver’s license in Norway. Today, as a parent himself, he aims to make art a family pursuit, recognizing its potential to stimulate young minds and cultivate critical thinking and a lifelong appreciation for visual arts.

The Barstad Collection places a high value on emotional resonance over rigid style constraints. It is drawn to artists who address important topics like social injustice and inequality. Their artworks convey thought-provoking, ironic, and humorous messages while guiding us towards meaningful conversations and introspective questions. This collection exhibits a fair balance of female artists’ work, a notable distinction of the next generation of collectors from their predecessors. This shift can be attributed to changing collective political and ethical perspectives within the community of young art buyers.

Millennial art collectors effortlessly navigate the digital art world, from joining art clubs with like-minded peers to purposefully travelling to discover the latest artistic treasures. When Henrik Barstad shares recent discoveries, his stories brim with enthusiasm, often mentioning names that are just on the rise. He plays a pivotal role in advancing their careers by acquiring artworks of these individuals, as is evident from his unconventional choice of prominently displayed photography in his home. Art lovers like him are actively reshaping the traditional art market, driven by unique collecting motivations and their personal interpretation of the profound value that art adds to their lives.

Henrik Barstad

You just returned from the Chart Fair and Enter Fair in Copenhagen. How did it go?

The CHART fair, located in the Charlottenborg district of Copenhagen, is perfect for gaining a focused, quick overview of the Nordic art market. The prices of the artworks offered there felt more affordable. On the other hand, the Enter Art Fair is more international, diverse, and considerably larger, featuring higher-priced material. In general, there was a wide range between unique, stand-out pieces and those that didn’t captivate me as much.

Any new artistic position that you discovered or found intriguing?

Oh, yes. During my time in Copenhagen, I encountered a work by Young-jun Tak titled Our Holding in Their Gaze. It was on view at his solo exhibition Street Religion at Palace Enterprise. The sculpture resembles a Christmas tree, with glossy dark green ceramic components hanging on a naked, tree-like rusty metal structure. Each ceramic piece is cast based on the body parts of an actual gay couple, one East Asian and one European, from their heads to their feet, and only their holding hands in the middle suggests their intimacy. Palace Enterprise is a truly cool gallery in Copenhagen that typically showcases experimental and cutting-edge artistic positions.

No one ever forgets their first art purchase. The stories and motivations behind art collecting are unique and fascinating. What’s your story?

I grew up in an art-filled household, where visiting museums was an integral part of our childhood. However, what sparked my passion for collecting art was my mother’s best friend’s collection. She was an avid collector. Her collection comprised a diverse array of forms and genres, featuring challenging pieces that spanned the spectrum from dystopian and political works to more conventional motifs like figurative art and landscapes. Notably, the majority of her collection hailed from Norwegian contemporary artists rather than international ones. I guess collecting foreign art is a younger generation collector’s approach.

When I was 16 or 17 years old, I volunteered to serve at her 60th-anniversary party. During breaks between servings, I explored her house, admiring the artwork and diligently noting down the artists’ names. A few weeks later, I managed to purchase a piece from one of the artists whose work she had in her collection, selecting one that was within my budget at the time. Her collection became my muse, and I made a promise to myself that I, too, would one day live surrounded by art, just as she did.

Sølvkua (Silver Cow) (1976) by Svein Rønning / Courtesy Barstad Collection

Wow, you were just a teenager... May I ask what was the first ‘seed’ in your collection, and do you still have it?

Yes, of course, I have it. It is a 1976 silk print, Sølvkua (or Silver Cow), by Svein Rønning.

What is the prevailing trend among Norwegian art buyers and seasoned collectors, and do you primarily acquire works by Nordic artists?

Personally, I have a strong affinity for American art. However, I’ve observed that Norwegians tend to prioritize purchasing art from local artists, often favoring the top artists from their own cities or regions, whether it’s in Bergen, Kristiansand, or Oslo. I believe this is the right approach – supporting living, local artists. Nevertheless, collectors in my social circle diversify their art collections by exploring the international art scene at events like Art Basel, Frieze London, and the Enter Art Fair.

Norwegians certainly have a passion for art, and they love improving their homes. After residing in an apartment for about five years, it’s a common desire to give it a fresh look. Notably, I’ve noticed a trend among Norwegians reallocating a portion of their budget to incorporate art into their private spaces. We are very proud of the newly opened National Museum in Oslo, which has already served us fantastic exhibitions by artists like Louise Bourgois, Sandra Mujinga, and Alice Neel. Additionally, Norway boasts excellent and forward-thinking art institutions like Bergen Kunsthall, Henie Onstad Art Center, and Astrup Fearnley, which continue to inspire and excite art enthusiasts in the country.

Wolfgang Tillmans. Paperdrop light b. 2019 / Courtesy of Henrik Barstad

Has the presence of the sea in any way influenced your relationship with art? In your opinion, how has the local natural environment influenced your personality?

Despite the sometimes deafening roar of the crashing waves in the North, it tends to put me in a tranquil state, giving me a sense of purpose, direction, and hope—a sentiment that resonates similarly when engaging with artworks.

Norway’s extensive coastline has influenced both its people and the artists who have flourished here throughout history. From the iconic works of Edvard Munch to the contemporary artists of today, the sea remains a timeless wellspring of inspiration. Personally, I’ve a profound admiration for the expressive use of cobalt blue, or the so-called ‘Nupen blue’, by the Norwegian artist Kjell Nupen in his seascapes. Many Norwegian households take pride in displaying artworks that capture the essence of the sea—its unique light, the lighthouses, and the vibrant coastal communities.

What is the process of acquiring artwork—thoughtful consideration or spontaneity?

Personally, I tend to adhere to a structured approach when it comes to acquiring art. It’s seldom a spontaneous decision, although I remain open to that possibility. Thus far, my method has been rather systematic. I frequently attend art fairs, not necessarily with the intention of making purchases, but to explore the offerings of various galleries. My goal here is to discover new galleries with compelling portfolios, progressive approaches, and exciting artistic perspectives. I gather information from the gallerists and evaluate findings. If I come across art I like, I learn about the artist and read interviews online, often on platforms like the Louisiana Channel. I also talk it over with my wife, who’s my partner in collecting. She helps us avoid playing it too safe. She asks a simple question: Does this artwork truly add to our lives? If not, she encourages me to consider more cutting-edge pieces.

The Prince Children (2019) by Buck Ellison / Courtesy of Henrik Barstad

Can you remember a situation where a piece in your collection sparked an interesting conversation?

Certainly, there’s a special artwork called The Prince Children (2019) by American conceptual photographer Buck Ellison. Here’s some background: It’s a staged family portrait featuring Betsy DeVos (née Prince), who became the education secretary under Donald Trump in 2017, despite lacking qualifications. Also included are her siblings, notably her brother Erik Prince, who founded Blackwater, a private military contractor. These individuals are influential figures in the US government, yet they remain relatively enigmatic. Like many members of America’s ultra-wealthy white upper class, there are very few publicly available photographs of them. In fact, when Vanity Fair published an article about them in 2018, the family declined to provide a photograph and instead, Vanity Fair created a hand-drawn illustration.

Buck Ellison created The Prince Children as part of a series where he carefully staged scenes with props and actors, reimagining the early life of these families in the 1970s. His art aims to uncover the hidden mechanisms that perpetuate inequality in a society that outwardly promotes democracy and equality. Many of these influential figures attain their positions through wealth and influence, rather than the typical democratic election process.

When guests see this 153 x 202 cm photograph displayed prominently in my living room, it sparks various questions and reactions. They often wonder about the identities of the young individuals in the photo and if they have any family connection to us.

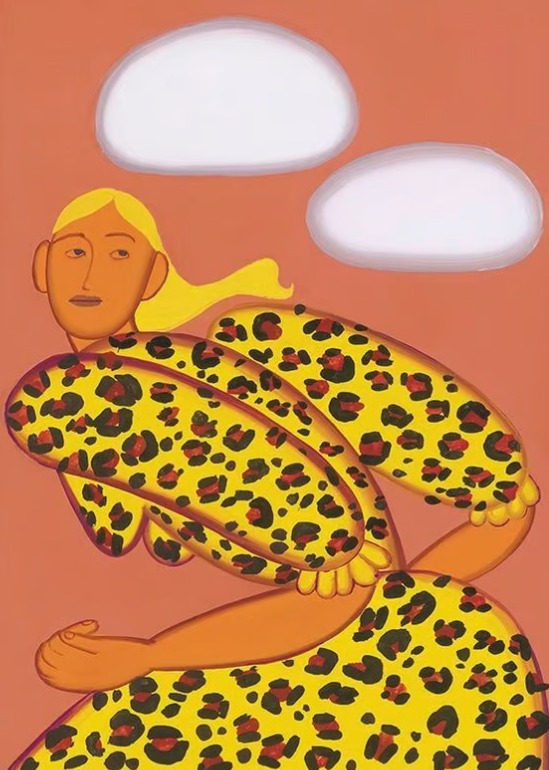

Nicole Eisenman. Purple Loose Strife. 2021 / Courtesy Barstad Collection

That’s a great example, and it’s not an easy piece to explain. How many pieces do you have in your collection, and do you have everything displayed in your private home, or are some pieces in storage?

I haven’t counted them, but I would guess I have between 35 and 40 pieces. Fortunately, I have space for most of them in my apartment. Artists in my collection include Wolfgang Tillmans, Buck Ellison, Torbjørn Rødland, Yves Scherer, Frida Orupabo, Nikita Gale, Grear Patterson, and paintings by Tyra Tingleff, Danielle Orchard, Grace Weaver, Nicole Eisenman, and Bjarne Melgaard. As the collection grows, some works are placed in my sister’s home. Luckily, she lives nearby and is very happy to display them on her walls.

What do you envision for the future of your collection?

Personally, I want to inspire my children. As a business developer and strategist, I should be adept at defining a direction and purpose for this collection. However, honestly, I’m also eager to see where it leads me. For me and my family, it’s far more significant that we connect with a piece of art than the piece itself connecting with my collection. My passion for art is deeply important to me.

Henrik Barstad with children

You mentioned that art is important to share with your children. What do they think of their parents’ growing collection?

I try to acquire art that might appeal also to them, whether it’s because of the colours or the subject. They have stunning figurative works by Danielle Orchard and Grace Weaver in their room, as well as some lenticular works by Swiss artist Yves Scherer. This is how we nurture their aesthetic sensibility and appreciation for visual art—by integrating art into their daily lives. They have even expressed that they would never want to part with these artworks. Sometimes, I notice them staring at the art, lost in thought, without saying anything or asking questions. I can see that a meaningful connection is forming between the painting and the young viewer. My eldest son even tries to convince his friends about why we have these works and explains to them what to look for.

Honestly, when I was a young kid, going to a gallery with my parents on a Saturday wasn’t very exciting. It’s the same with my kids, who are young and full of energy. So, we typically visit museums with dedicated children’s areas where they can draw and engage in programmes related to the exhibits. This has worked well, and my kids now suggest visiting museums for this reason.

Grace Weaver. Untitled. 2019

There’s an interesting story about Munch’s The Scream, currently housed in the museum in Oslo. Young children, when standing in front of this artwork, often claim to hear the scream.

When my kids first saw Skrik, they were taken by it, particularly by its unique presentation. The museum features three different versions of the artwork, but due to their sensitivity to light, only one can be viewed at any given time. Rotation takes place every hour, with one masterpiece fading into darkness as another emerges into the light, enhancing the sense of its preciousness. While my son found Skrik utterly fascinating, my two younger daughters were somewhat intimidated by its intense motif.

I notice that you’re particularly interested in photography.

That’s correct. Photography is my primary interest at the moment, although I’m not ruling out other art forms.

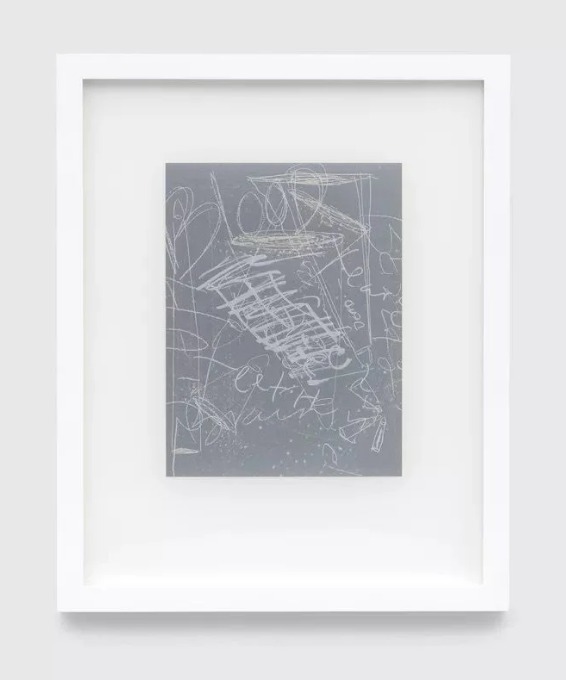

Have you come across any emerging photographers recently?

Have you heard of Nikita Gayle? Her career is on an exciting trajectory. Earlier this year, she had a show called End of Subject at 52 Walker, an adjacent space to the David Zwirner Gallery in Tribeca, New York. That’s where I discovered her. She combines various elements such as images, sound, concrete, steel, lights, and text while exploring the connections between them. I now have one of her prints, titled Teeth (2022), in my collection, and you can actually hear the sound within her prints.

Nikita Gale. Teeth. 2022 / Courtesy of Henrik Barstad

You can hear the sound from an image?

It’s more about evoking the sense of sound. By associating it with a metal board and chalk, you can imagine the sound that the image conveys.

So, every time you look at it, it generates a non-existent but squeaky sound based on the associations in your mind.

Yes.

In our rapidly changing digital world, how do you see the evolving relationship between traditional photography and contemporary digital art?

I believe traditional photography and contemporary digital art can complement each other and coexist harmoniously. Contemporary digital art has limitless possibilities and can be truly captivating. Video art can be tricky to follow through and understand. Nevertheless, introducing children to this art form can be a stimulating experience. It can make them curious and make them ask questions and share their thoughts, prompting questions and interpretations.

Recently, my son and I visited The Henie Onstad Triennial for Photography and New Media. There was one particular piece that left a strong impression on us. An artist used artificial intelligence to create images based on war stories. It was a powerful and important piece to showcase, despite its brutality. For example, Lithuanian artist Emilija Škarnulytė’s immersive video installation RAKHNE (2023), which envisions a massive, deep-sea data-storage unit using CGI, and highlights how corporations often disregard environmental concerns in their practices. It presents a futuristic scenario and serves as a powerful medium to depict it, offering a visually captivating way for children to engage with these important topics.

What’s your relationship with painting?

One of my favorite abstract painters is Tyra Tingleff, who is Norwegian but based in Berlin. She creates hallucinatory landscapes with colours and hues, and lines that weave through these surfaces as if trying to give some definition to the formless. The way she builds up countless layers of colour application just fascinates me. Her work was my first acquisition in the realm of abstract oil paintings.

Torbjørn Rødland. HotDog. 2013 / Courtesy of Henrik Barstad

What are your personal thoughts on what contemporary art can teach society and what it means to you?

The range of experiences that art can offer is immense. I believe that governments should provide even more support to the art scene, making great art accessible to the public. Government backing should also extend to major museums, aiding in their marketing efforts and ensuring that schools and individuals are informed about exhibitions and their significance, fostering interest and motivation to visit their shows. Not everyone can be a collector, but we can all visit museums.

What advice would you give to people interested in art who want to start their own collection?

First and foremost, I would recommend taking some risks. That’s exactly how I felt when I purchased my first piece of art. I was fortunate to discover an affordable artist whose works didn’t strain my finances. In hindsight, I made a relatively safe investment because I knew someone, a friend of my mom’s, who also collected art from the same artist. However, it’s crucial to find your own path and not simply follow what your neighbour or friend is buying. This approach will provide a more unique learning experience and emotional connection.

Buck Ellison. Dick and Betsy. The Ritz-Carlton, Dallas, Texas. 1984, 2019 Archival pigment print / Courtesy of Henrik Barstad

I suggest buying from the primary market, as it allows us to support artists in their ongoing development.

When I purchased Buck Ellison’s artwork The Prince Children, it was during the pandemic. Getting a hold of his piece wasn’t too difficult. There are three editions of The Prince Children—one is on display at the Hammer Museum, another at the Los Angeles County Museum (LACMA), and the third one is in my home. Now, three years later, American museums are showing interest in acquiring it. I feel somewhat conflicted about turning down their offers because it could have been a great opportunity for Ellison as a young artist. Nevertheless, I was the first one to be moved by his work, and my family and I genuinely love this piece.